Volume 3, Issue 3 (Spring 2018 -- 2018)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2018, 3(3): 167-174 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mehraein Nazdik Z, Mohammadi M. Comparing Shiraz and Kerman High School Students' Knowledge for an Earthquake Encountering. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2018; 3 (3) :167-174

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-157-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-157-en.html

1- Department of Disaster Management, Faculty of Management and Economics, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman, Iran. , z.mehraein@gmail.com

2- Department of Administration & Educational Planning, School of Education & Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

2- Department of Administration & Educational Planning, School of Education & Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 645 kb]

(1816 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4501 Views)

Full-Text: (1324 Views)

1. Introduction

rises are serious menaces for human life, and an effective plan to reduce the hazards resulting from them often depends on the participation of the community and various groups of people. Based on the community-based crisis management, local people have relative knowledge on their vulnerability and capacities and also mechanisms to confront crises [1]. However, there is a considerable difference between the perception of households and communities with proper and timely actions. Accordingly, crisis managers, by intervening in community awareness are trying to improve the level of preparedness of the communities toward crises by changing their behavior. Training has long been recognized as the most effective means of intervention at the levels of knowledge and awareness of individuals. Studies indicate that the annual cost of training the managers and employees of organizations in the United States are more than forty billion USD [2]. Due to the fact that the age by which the learning process begins is an effective element, the focus of many of these interventions is on children and adolescents.

In our country too, educational measures have been taken to improve the knowledge level of students in the field of crisis. However, these educational measures have been limited only to earthquake hazards. However, due to its crisis management, the earthquake hazard has a special station among other hazards in Iran. Because of its unpredictable nature, the earthquake in case of unpreparedness would lead to innumerable casualties, fatalities, and damages. Eighty percent of fatalities due to earthquake have been in the 6 countries, namely China, Iran, Peru, the former Soviet ::union::, Guatemala, and Turkey [3]. Many cities such as Tehran, Tabriz, Rudbar, Manjil, Tabas, Lar, Qazvin, Zanjan, Hamedan, and Kermanshah have been prone to damages and losses resulting from earthquake [4]. Statistics indicate that at least 16 major earthquakes took place in the vicinity of the city of Shiraz between 1291 AD and 1894 AD; the magnitude of which had been between 5.9 and 7.1 [5]. The city of Kerman, in the southeast of Iran, also is located on one of the most active earthquake faults in Iran, where 437 earthquakes took place between 1907 and 2005 within the 300 kilometer radius of that city and had a magnitude larger than 4 degrees on the Richter scale [6].

Since earthquake can lead to destruction of school buildings and disruption in the function of educational systems and also because the first responders will be school officials and students [7], an increase in the awareness and knowledge of students as the major part of individuals in any school for confronting the earthquake hazard is of utmost importance. The first step in making appropriate policies to enhance this awareness level and subsequently to improve the function of individuals toward the hazard of an earthquake is to assess the current level of their awareness and knowledge in this regard and to discover the weak points therein.

The importance of the assessment role in this process is in a way that the absence or the weakness in assessment and the feedback system would make it impossible to exchange the required information for growth, development, and improvement of preparation activities and would create the grounds for problems to occur, which eventually leads to the breakdown and loss of resources [8]. Until now, no specific research has been conducted in this regard in Iran. Even among foreign resources, the numbers of such studies are limited, and a comparison between the earthquake hit regions has not taken place. In 2015, Ozkazanc & Yuksel conducted a study titled “Assessment of the level of knowledge and alertness of students of advance academic studies in Turkey regarding crisis.” By using a questionnaire which its questions were designed based on preparation before, during, and after a crisis they reached these findings:

The knowledge level of those students was low. Average score related to their knowledge level on flood, landslide, and fire was 2.21 (out of 5 points) [9]. Sinha and colleagues (2008) conducted a research in India with the objective of evaluating the knowledge level of students of medical sciences regarding their readiness when facing a crisis. Their findings showed that the student’s level of knowledge in that regard is very insignificant. The average number of scores received by the students was 8.77 (out of 15 points) and was estimated to be equal to 58.46%. The knowledge levels of girls were slightly better than boys, and the highest level of awareness was related to the age group of 26-30 [10].

Guo and Li (2016) conducted a study in Japan titled “Preparation for Severe Calamities: The role of past experiences in change of knowledge on calamities” and reached to the conclusion that the awareness of people of Japan in these regards has significantly increased. Their study showed that direct experiences, recalling past experiences, and also indirect experiences have an effective role in increasing the knowledge of people and creating an impetus for learning and prevention [11]. Shaw and colleagues (2004) in a study proceeded to investigate the effect of experiencing the earthquake and education on alertness and readiness of Japanese students. The results of their research indicated the combined effectiveness of past experiences and training on students. Moreover, in that study, emphasis was made on the principal role of self teaching, the family, and the society on the alertness and readiness of students [12].

Our research was conducted with the objective of investigating, with a comparative approach, the knowledge of students of junior high schools of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman for confronting the earthquake hazards. Since the province of Kerman having had the experience of earthquake at the city of Bam (not far from Kerman) in 2003 has a suitable capacity for confronting the earthquake, in view of the authors of this study the comparison of the knowledge level of students of the two cities of Shiraz and Kerman can provide a proper feedback to the officials of either of these two cities. Figure 1 shows the model used in this research. The dimensions of the students’ knowledge were divided into three principal categories: awareness of necessary measures that are needed before earthquake, knowledge of necessary measures needed to be taken during a possible earthquake, and knowledge of necessary steps needed after the earthquake happened.

rises are serious menaces for human life, and an effective plan to reduce the hazards resulting from them often depends on the participation of the community and various groups of people. Based on the community-based crisis management, local people have relative knowledge on their vulnerability and capacities and also mechanisms to confront crises [1]. However, there is a considerable difference between the perception of households and communities with proper and timely actions. Accordingly, crisis managers, by intervening in community awareness are trying to improve the level of preparedness of the communities toward crises by changing their behavior. Training has long been recognized as the most effective means of intervention at the levels of knowledge and awareness of individuals. Studies indicate that the annual cost of training the managers and employees of organizations in the United States are more than forty billion USD [2]. Due to the fact that the age by which the learning process begins is an effective element, the focus of many of these interventions is on children and adolescents.

In our country too, educational measures have been taken to improve the knowledge level of students in the field of crisis. However, these educational measures have been limited only to earthquake hazards. However, due to its crisis management, the earthquake hazard has a special station among other hazards in Iran. Because of its unpredictable nature, the earthquake in case of unpreparedness would lead to innumerable casualties, fatalities, and damages. Eighty percent of fatalities due to earthquake have been in the 6 countries, namely China, Iran, Peru, the former Soviet ::union::, Guatemala, and Turkey [3]. Many cities such as Tehran, Tabriz, Rudbar, Manjil, Tabas, Lar, Qazvin, Zanjan, Hamedan, and Kermanshah have been prone to damages and losses resulting from earthquake [4]. Statistics indicate that at least 16 major earthquakes took place in the vicinity of the city of Shiraz between 1291 AD and 1894 AD; the magnitude of which had been between 5.9 and 7.1 [5]. The city of Kerman, in the southeast of Iran, also is located on one of the most active earthquake faults in Iran, where 437 earthquakes took place between 1907 and 2005 within the 300 kilometer radius of that city and had a magnitude larger than 4 degrees on the Richter scale [6].

Since earthquake can lead to destruction of school buildings and disruption in the function of educational systems and also because the first responders will be school officials and students [7], an increase in the awareness and knowledge of students as the major part of individuals in any school for confronting the earthquake hazard is of utmost importance. The first step in making appropriate policies to enhance this awareness level and subsequently to improve the function of individuals toward the hazard of an earthquake is to assess the current level of their awareness and knowledge in this regard and to discover the weak points therein.

The importance of the assessment role in this process is in a way that the absence or the weakness in assessment and the feedback system would make it impossible to exchange the required information for growth, development, and improvement of preparation activities and would create the grounds for problems to occur, which eventually leads to the breakdown and loss of resources [8]. Until now, no specific research has been conducted in this regard in Iran. Even among foreign resources, the numbers of such studies are limited, and a comparison between the earthquake hit regions has not taken place. In 2015, Ozkazanc & Yuksel conducted a study titled “Assessment of the level of knowledge and alertness of students of advance academic studies in Turkey regarding crisis.” By using a questionnaire which its questions were designed based on preparation before, during, and after a crisis they reached these findings:

The knowledge level of those students was low. Average score related to their knowledge level on flood, landslide, and fire was 2.21 (out of 5 points) [9]. Sinha and colleagues (2008) conducted a research in India with the objective of evaluating the knowledge level of students of medical sciences regarding their readiness when facing a crisis. Their findings showed that the student’s level of knowledge in that regard is very insignificant. The average number of scores received by the students was 8.77 (out of 15 points) and was estimated to be equal to 58.46%. The knowledge levels of girls were slightly better than boys, and the highest level of awareness was related to the age group of 26-30 [10].

Guo and Li (2016) conducted a study in Japan titled “Preparation for Severe Calamities: The role of past experiences in change of knowledge on calamities” and reached to the conclusion that the awareness of people of Japan in these regards has significantly increased. Their study showed that direct experiences, recalling past experiences, and also indirect experiences have an effective role in increasing the knowledge of people and creating an impetus for learning and prevention [11]. Shaw and colleagues (2004) in a study proceeded to investigate the effect of experiencing the earthquake and education on alertness and readiness of Japanese students. The results of their research indicated the combined effectiveness of past experiences and training on students. Moreover, in that study, emphasis was made on the principal role of self teaching, the family, and the society on the alertness and readiness of students [12].

Our research was conducted with the objective of investigating, with a comparative approach, the knowledge of students of junior high schools of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman for confronting the earthquake hazards. Since the province of Kerman having had the experience of earthquake at the city of Bam (not far from Kerman) in 2003 has a suitable capacity for confronting the earthquake, in view of the authors of this study the comparison of the knowledge level of students of the two cities of Shiraz and Kerman can provide a proper feedback to the officials of either of these two cities. Figure 1 shows the model used in this research. The dimensions of the students’ knowledge were divided into three principal categories: awareness of necessary measures that are needed before earthquake, knowledge of necessary measures needed to be taken during a possible earthquake, and knowledge of necessary steps needed after the earthquake happened.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study is of the descriptive-surveying type that was conducted during the school year 2014-2015 in the cities of Shiraz and Kerman. The statistical population of this research included all the students of junior high schools of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman (Table 1). To compute the sample volume, the Cochran formula was used and considered at the confidence level of 95% and the margin of error was considered as 0.05. Sample volumes in the cities of Shiraz and Kerman were 380 and 376 students, respectively and the questionnaire was distributed among them. A total of 369 of the Shirazi students and 350 of the Kermani students provided usable responses to the questions, and the questionnaires given to them were analyzed. Samples were selected through the cluster sampling method and entered the research in a way that based on the students of each district the sample volume of that district was calculated.

The present study is of the descriptive-surveying type that was conducted during the school year 2014-2015 in the cities of Shiraz and Kerman. The statistical population of this research included all the students of junior high schools of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman (Table 1). To compute the sample volume, the Cochran formula was used and considered at the confidence level of 95% and the margin of error was considered as 0.05. Sample volumes in the cities of Shiraz and Kerman were 380 and 376 students, respectively and the questionnaire was distributed among them. A total of 369 of the Shirazi students and 350 of the Kermani students provided usable responses to the questions, and the questionnaires given to them were analyzed. Samples were selected through the cluster sampling method and entered the research in a way that based on the students of each district the sample volume of that district was calculated.

After preparing the complete list of schools in each of the four districts of the city of Shiraz and the two districts of the city of Kerman through random sampling a number of schools were designated. In the next stage, by personal referral to each school based on its population, a number of students were selected as sample, and the questionnaires were distributed and filleted out. Data collection tool was the researcher compiled questionnaire whose validity was examined and confirmed by ten specialists in the field of crisis. To assess the reliability the Cronbach’s alpha test, most used test for assessing components’ compliance validation, was used. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated using the software SPSS and was obtained to be 0.65.

The final questionnaire included 24 specialized questions with the following topics: knowledge of exigent measures before the occurrence of an earthquake, knowledge of exigent measures during the possible earthquake, and knowledge of exigent measures after the occurrence of an earthquake. Every correct response, based on the questionnaire’s key received one point and erroneous response, received zero point. The software used to analyze data was SPSS 22. The research questions were examined through two sample t-Test, and the variance analysis was used to compare the level of knowledge of the students as separated by gender.

3. Results

Considering the data analysis, from among 719 students under the study, 79.3% of the students were between the ages of 13 and 14, and 42.4% were boys and 57.6% were girls. As can be observed from Table 2, the knowledge scores of 23.6% and 27.1% of Shirazi students and 30.6% and 24.6% of Kermani students on exigent measures before the occurrence of an earthquake were between 0.20 and 0.40 and between 0.40 and 0.60%, respectively. Furthermore, 12.2% of Shirazi students received scores of 0-0.20 which is about 8.5% higher than the Kermani students. Therefore, the knowledge level of Kermani students found to be higher than the Shirazi students on exigent measures prior to the occurrence of an earthquake. The knowledge level of 40.9% and 32.5% of Shirazi students and 44.6% and 40.9% of the Kermani students regarding exigent measures during a possible earthquake was between 0.40 and 0.60 and between 0.60 and 0.80, respectively. Further, the score of the knowledge levels of 29% and 31.2% of Shirazi students and 29.7% and 26.6% of Kermani students on exigent measures after the occurrence of an earthquake were between 0.20 and 0.40 and between 0.40 and 0.60, respectively.

The final questionnaire included 24 specialized questions with the following topics: knowledge of exigent measures before the occurrence of an earthquake, knowledge of exigent measures during the possible earthquake, and knowledge of exigent measures after the occurrence of an earthquake. Every correct response, based on the questionnaire’s key received one point and erroneous response, received zero point. The software used to analyze data was SPSS 22. The research questions were examined through two sample t-Test, and the variance analysis was used to compare the level of knowledge of the students as separated by gender.

3. Results

Considering the data analysis, from among 719 students under the study, 79.3% of the students were between the ages of 13 and 14, and 42.4% were boys and 57.6% were girls. As can be observed from Table 2, the knowledge scores of 23.6% and 27.1% of Shirazi students and 30.6% and 24.6% of Kermani students on exigent measures before the occurrence of an earthquake were between 0.20 and 0.40 and between 0.40 and 0.60%, respectively. Furthermore, 12.2% of Shirazi students received scores of 0-0.20 which is about 8.5% higher than the Kermani students. Therefore, the knowledge level of Kermani students found to be higher than the Shirazi students on exigent measures prior to the occurrence of an earthquake. The knowledge level of 40.9% and 32.5% of Shirazi students and 44.6% and 40.9% of the Kermani students regarding exigent measures during a possible earthquake was between 0.40 and 0.60 and between 0.60 and 0.80, respectively. Further, the score of the knowledge levels of 29% and 31.2% of Shirazi students and 29.7% and 26.6% of Kermani students on exigent measures after the occurrence of an earthquake were between 0.20 and 0.40 and between 0.40 and 0.60, respectively.

Accordingly, it can be said that there were no significant differences between the knowledge levels of Kermani and Shirazi students regarding the exigent measures during and after the occurrence of earthquake. General knowledge scores of 59.4% and 27.1% of Kermani students and 54.5% and 23.6% of Shirazi students were between 40 and 60 and between 60 and 80, respectively. Furthermore, 20.6% of Shirazi students had scores of 0.20-0.40 which was significantly higher than the Kermani students. Therefore, the general knowledge level of the Kermani students is considered higher than the Shirazi students.

There is a significant difference between the knowledge levels of the students of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman for confronting the earthquake hazard. Based on Table 3, it can be observed that the level of knowledge of the students of the city of Kerman for facing earthquake hazard is higher than the students of the city of Shiraz. Moreover, based on t value obtained in the degree of freedom 717, a significant difference was observed at 0.008 level between the average levels of the knowledge of the students in the two groups.

There is a significant difference between the knowledge levels of the students of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman for confronting the earthquake hazard. Based on Table 3, it can be observed that the level of knowledge of the students of the city of Kerman for facing earthquake hazard is higher than the students of the city of Shiraz. Moreover, based on t value obtained in the degree of freedom 717, a significant difference was observed at 0.008 level between the average levels of the knowledge of the students in the two groups.

There is a significant difference between the knowledge levels of the students of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman regarding exigent measures prior to earthquake. Based on Table 4, it can be observed that the knowledge level of the students of the city of Kerman on exigent measures before earthquake is higher than the students of Shiraz. Based on the t value arrived at degree of freedom 717, a significant difference was observed at 0.002 level between the knowledge levels of the students in the two groups.

There is no significant difference between the knowledge levels of the students of the city of Shiraz and Kerman regarding the exigent measures during a possible earthquake. Based on Table 5, although the average knowledge level of the students of the city of Kerman (0.64) on exigent measures during a possible earthquake is higher than the students of the city of Shiraz (0.61), based on the t value arrived at (-1.83) in the degree of freedom 717 no significant difference was observed between the knowledge levels of the two groups on exigent measures during a possible earthquake.

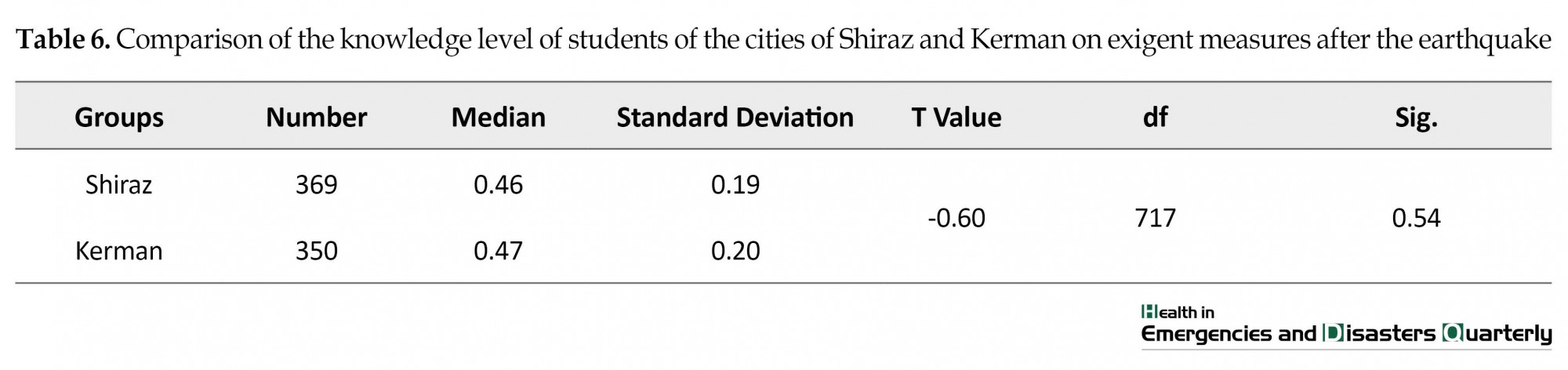

There is no significant difference between the knowledge levels of students of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman on exigent measures after the earthquake. Based on Table 6, although the average knowledge level of students of the city of Kerman (0.47) on exigent measures after the earthquake is higher than the knowledge level of students of the city of Shiraz (0.46), based on the t value arrived at (-0.60) in the degree of freedom 717 no significant difference was found between the knowledge levels of the two groups on exigent measures during a possible earthquake.

There is no significant difference between the knowledge levels of boy and girl students of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman for confronting the earthquake hazard. Based on Table 7, it can be observed that the highest level of knowledge belongs to Kermani boy students (0.55) and the lowest knowledge level belongs to Shirazi girl students (0.48); however, based on the t value arrived at (0.005) in the degrees of freedom 1 and 715 no significant difference exists between the knowledge level of Shirazi and Kermani boy and girl students (Table 8).

4. Discussion

The present study was conducted in an attempt to compare the knowledge of junior high school students of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman on confronting the earthquake hazards. Moreover, in this study, it was assumed that the students were acquainted with exigent measures for confronting the earthquake hazard. Based on the questions mentioned in the questionnaire, 92.1% of Shirazi and Kermani students referred to the effect of education and the necessity of knowledge to confront the earthquake hazard, and also 99.4% by that time had experienced the earthquake. Considering that in our country training and education regarding prevention of earthquake hazard are provided based on the three stages of before, during, and after the earthquake, in this article, in addition to comparing the knowledge level of Shirazi and Kermani students, the knowledge of all of the students in each of these dimensions was separately examined.

The knowledge levels of Shirazi and Kermani students in exigent measures needed to be taken before, during, and after the occurrence of earthquake, despite its serious hazards, is lower than the desired level. About 75.4% of Shirazi students and 71.1% of Kermani students had scores between 0 and 0.60. Based on the findings of most researchers, such as Sinha (2008) and Ozkazanc, it can be inferred that the knowledge level of the students in the present study was not at an appropriate level. The average knowledge level in the study by Sinha and colleagues in 2008 was 58.4 percent (out of 100 points), in the study by Ozkazanc and Yuksel in 2015 it was equal to 2.21 (out of 5 points), and in the research by Al-Thobaity and colleagues [13] in 2015 it was equal to 4.16 (out of 6 points), whereas in this research it was equal to 0.50 (out of 1.00 points) for Shirazi students and 0.53 for Kermani students.

The students’ knowledge level on exigent measures during a possible earthquake was relatively higher. About 73.4% of Shirazi students and 85.5% of Kermani students had scores between 0.40 and 0.80. Moreover, 95.4% of the students knew how to protect head and neck when taking shelter. In the study by Ozkazanc, 39.6% of the students were aware of this protective measure. It seems that this is due to the focus made by instructors in teaching these measures to the students.

In a comparison that took place between the knowledge levels of Shirazi and Kermani students, the knowledge level of Kermani students was assessed to be higher than the Shirazi students. Considering the dimensions of the research, this difference in the knowledge levels was on exigent measures that needed to be taken before the occurrence of earthquake, while in the exigent measures during and after the earthquake no difference was observed between the two groups. The city of Kerman is located near the city of Bam, and the tragic earthquake at Bam led to officials and people of the province of Kerman to be more heedful than others for confronting the hazards and impacts resulting from earthquakes and to perceive more the necessity for prevention and preparedness.

Results of this part of our research are consistent with the findings of Guo and Li indicating the effectiveness of direct and indirect experiences to enhance the knowledge of individuals [11]. In addition, the study by Shaw and colleagues is demonstrative of the effectiveness of these experiences on the knowledge of individuals [12]. In fact, the direct experience of calamities provides a credible knowledge of them that can be a suitable path opener for future hazardous situations. According to the reports of the office of Japan’s cabinet of government ministers, from 2004 to 2013 there were 302 earthquakes in that country with the magnitude of larger than 6 on the Richter scale [14]. Currently, Japan is recognized as a country with a proper culture of safety and preparedness [11]. Therefore, strengthening the memories of crises based on past experiences can be one of the strategies to increase the knowledge level of the individuals in the society, especially the kids and adolescents. Human beings are able to learn directly and indirectly from past experiences and use them for correct behavior.

5. Conclusion

Based on the findings of this research, it can be stated that the students did not have an appropriate knowledge level in confronting the earthquake hazard. In many studies including the research by Alim and colleagues which was conducted in Japan in 2015 [15], the effectiveness and usefulness of education and training to improve level of knowledge has been proven. However, the important point is that we should be in the quest for the factors that upgrade these trainings.

Therefore, it is recommended that new educational methods with the objective of internalizing the materials, such as the game method, should be employed for educating the students with regard to accidents and calamities. Furthermore, the knowledge of Kermani students on exigent measures prior to earthquake was higher than the Shirazi students. These measures include familiarity with first aid, the use of fire extinguisher and which by organizing mobilization of workshops against calamities would place the students in direct contact with these skills. By taking part in these workshops, first aid, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and can be taught in practical form to the students, their parents, and even to the school officials. Today, many schools throughout the world train their students through administering these courses. Furthermore, the guidebooks published by UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and the United States’ Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) can be used for further enrichment of educational materials in this scenario.

Ethical considerations

The questionnaire, the subject, and the implementation of research process took place with prior review by experts and assessors of the general office of education of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman. Furthermore, they were informed of pre-completed student questionnaire on the subject of research, the objective, and the research implementation process. The students who were inclined to take part in the research were asked to fill out the questionnaire.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study hereby express their appreciation toward the sincere cooperation of all of the school superintendents of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman whose students took part in this study, especially those of the girls’ schools of Narges and Tuba of the city of Shiraz. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

The present study was conducted in an attempt to compare the knowledge of junior high school students of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman on confronting the earthquake hazards. Moreover, in this study, it was assumed that the students were acquainted with exigent measures for confronting the earthquake hazard. Based on the questions mentioned in the questionnaire, 92.1% of Shirazi and Kermani students referred to the effect of education and the necessity of knowledge to confront the earthquake hazard, and also 99.4% by that time had experienced the earthquake. Considering that in our country training and education regarding prevention of earthquake hazard are provided based on the three stages of before, during, and after the earthquake, in this article, in addition to comparing the knowledge level of Shirazi and Kermani students, the knowledge of all of the students in each of these dimensions was separately examined.

The knowledge levels of Shirazi and Kermani students in exigent measures needed to be taken before, during, and after the occurrence of earthquake, despite its serious hazards, is lower than the desired level. About 75.4% of Shirazi students and 71.1% of Kermani students had scores between 0 and 0.60. Based on the findings of most researchers, such as Sinha (2008) and Ozkazanc, it can be inferred that the knowledge level of the students in the present study was not at an appropriate level. The average knowledge level in the study by Sinha and colleagues in 2008 was 58.4 percent (out of 100 points), in the study by Ozkazanc and Yuksel in 2015 it was equal to 2.21 (out of 5 points), and in the research by Al-Thobaity and colleagues [13] in 2015 it was equal to 4.16 (out of 6 points), whereas in this research it was equal to 0.50 (out of 1.00 points) for Shirazi students and 0.53 for Kermani students.

The students’ knowledge level on exigent measures during a possible earthquake was relatively higher. About 73.4% of Shirazi students and 85.5% of Kermani students had scores between 0.40 and 0.80. Moreover, 95.4% of the students knew how to protect head and neck when taking shelter. In the study by Ozkazanc, 39.6% of the students were aware of this protective measure. It seems that this is due to the focus made by instructors in teaching these measures to the students.

In a comparison that took place between the knowledge levels of Shirazi and Kermani students, the knowledge level of Kermani students was assessed to be higher than the Shirazi students. Considering the dimensions of the research, this difference in the knowledge levels was on exigent measures that needed to be taken before the occurrence of earthquake, while in the exigent measures during and after the earthquake no difference was observed between the two groups. The city of Kerman is located near the city of Bam, and the tragic earthquake at Bam led to officials and people of the province of Kerman to be more heedful than others for confronting the hazards and impacts resulting from earthquakes and to perceive more the necessity for prevention and preparedness.

Results of this part of our research are consistent with the findings of Guo and Li indicating the effectiveness of direct and indirect experiences to enhance the knowledge of individuals [11]. In addition, the study by Shaw and colleagues is demonstrative of the effectiveness of these experiences on the knowledge of individuals [12]. In fact, the direct experience of calamities provides a credible knowledge of them that can be a suitable path opener for future hazardous situations. According to the reports of the office of Japan’s cabinet of government ministers, from 2004 to 2013 there were 302 earthquakes in that country with the magnitude of larger than 6 on the Richter scale [14]. Currently, Japan is recognized as a country with a proper culture of safety and preparedness [11]. Therefore, strengthening the memories of crises based on past experiences can be one of the strategies to increase the knowledge level of the individuals in the society, especially the kids and adolescents. Human beings are able to learn directly and indirectly from past experiences and use them for correct behavior.

5. Conclusion

Based on the findings of this research, it can be stated that the students did not have an appropriate knowledge level in confronting the earthquake hazard. In many studies including the research by Alim and colleagues which was conducted in Japan in 2015 [15], the effectiveness and usefulness of education and training to improve level of knowledge has been proven. However, the important point is that we should be in the quest for the factors that upgrade these trainings.

Therefore, it is recommended that new educational methods with the objective of internalizing the materials, such as the game method, should be employed for educating the students with regard to accidents and calamities. Furthermore, the knowledge of Kermani students on exigent measures prior to earthquake was higher than the Shirazi students. These measures include familiarity with first aid, the use of fire extinguisher and which by organizing mobilization of workshops against calamities would place the students in direct contact with these skills. By taking part in these workshops, first aid, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and can be taught in practical form to the students, their parents, and even to the school officials. Today, many schools throughout the world train their students through administering these courses. Furthermore, the guidebooks published by UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and the United States’ Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) can be used for further enrichment of educational materials in this scenario.

Ethical considerations

The questionnaire, the subject, and the implementation of research process took place with prior review by experts and assessors of the general office of education of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman. Furthermore, they were informed of pre-completed student questionnaire on the subject of research, the objective, and the research implementation process. The students who were inclined to take part in the research were asked to fill out the questionnaire.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study hereby express their appreciation toward the sincere cooperation of all of the school superintendents of the cities of Shiraz and Kerman whose students took part in this study, especially those of the girls’ schools of Narges and Tuba of the city of Shiraz. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Izadkhah YO, Hosseini M. Sustainable neighbourhood earthquake emergency planning in megacities. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. 2010; 19(3):345–57. doi: 10.1108/09653561011052510

- Hadavandi M, Hadavandi F. Evaluating the effectiveness of the Kerman training course on crisis management in 2009. Journal of Rescue and Relief. 2009; 2(1):17-32.

- Ahadnezhad Rooshti M, Jalilpour Sh. [Evaluation of external impact factors on structural vulnerability of old towns toward earthquake (Case study: District 1 of Khoy City) (Persian)]. Paper presented at the National Seminar on GIS in the planning of economic, social and urban. 11 May 2011, Tehran, Iran.

- PourReza A, Tohidi H, Rafiee S. [The effect of education on knowledge and practice of individuals in coping with earthquakes (Persian)]. Journal of Hospital. 2009; 8(5):3-18.

- Moshksaz P, Izadi H, Soltani A, Bazrgar MR. [Physical vulnerability assessment of urban fabrics against earthquake by RADIUS method (Case study: Shiraz City, 3rd Municipal District) (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Geographical Research Urban Planning. 2014; 1(1):115-29.

- Hasanzadeh R, Abbas Nejad A, Alawi A, Sharifi Tashnizi A. [Seismic hazard analysis of Kerman city with emphasis on application in grade 2 micro-zoning (Persian)]. Journal of Geosciences. 2010; 21(81):23-30.

- Kano M, Bourque LB. Experiences with and preparedness for emergencies and disasters among public schools in California. NASSP Bulletin. 2007; 91(3):201–18. doi: 10.1177/0192636507305102

- Nikokar GhH, Sajjadi Panah A, Rayej A, Sajjadi Panah M. [Designing a Model for Measuring the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Military Higher Education Centers (Persian)]. Journal of Public Administration. 2009; 1(3): 155-74.

- Ozkazanc S, Yuksel UD. Evaluation of disaster awareness and sensitivity level of higher education students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015; 197:745–53. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.168

- Sinha A, Pal DK, Kasar PK, Tiwari R, Sharma A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of disaster preparedness and mitigation among medical students. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. 2008; 17(4):503–7. doi: 10.1108/09653560810901746

- Guo Y, Li Y. Getting ready for mega disasters: The role of past experience in changing disaster consciousness. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. 2016; 25(4):492–505. doi: 10.1108/dpm-01-2016-0008

- Shaw R, Shiwaku Hirohide Kobayashi K, Kobayashi M. Linking experience, education, perception and earthquake preparedness. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. 2004; 13(1):39–49. doi: 10.1108/09653560410521689

- Al Thobaity A, Plummer V, Innes K, Copnell B. Perceptions of knowledge of disaster management among military and civilian nurses in Saudi Arabia. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2015; 18(3):156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2015.03.001

- Cabinet Office. Disaster management in Japan. Tokyo: Director General for Disaster Management; 2015.

- Alim S, Kawabata M, Nakazawa M. Evaluation of disaster preparedness training and disaster drill for nursing students. Nurse Education Today. 2015; 35(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.04.016

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

General

Received: 2017/12/18 | Accepted: 2018/03/3 | Published: 2018/04/1

Received: 2017/12/18 | Accepted: 2018/03/3 | Published: 2018/04/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |