Volume 3, Issue 4 (Summer 2018 -- 2018)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2018, 3(4): 215-220 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shabanikiya H, Gholami Fadihegi M. Strategy to Increase Pediatric Department Capacity of Selected Hospitals During Disasters . Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2018; 3 (4) :215-220

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-194-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-194-en.html

1- Department of Health Management and Economics, School of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. , shabanikiahr@mums.ac.ir

2- Department of Health Management and Economics, School of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran., Faculty of Health, Daneshgah Ave. #18, Mashhad-Iran, Tel.: (+98 51) 38515115

2- Department of Health Management and Economics, School of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran., Faculty of Health, Daneshgah Ave. #18, Mashhad-Iran, Tel.: (+98 51) 38515115

Full-Text [PDF 580 kb]

(1767 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6029 Views)

Full-Text: (1305 Views)

1. Introduction

inding solutions to increase hospital surge capacity in disaster has always been one of the challenges of preparedness and response to disasters [1]. Early discharge of inpatients during disasters is among the most effective and fastest ways to create surge capacity [2-4]. Early inpatient discharge refers to the discharge of a hospitalized patient (before a disaster) from the hospital to increase the surge capacity, if there is no mortality risk for at least the next 72 hours ahead or possibility of serious complications arising from the discontinuation of the treatment process [5]. Awareness of the surge capacity that can be achieved by adopting in a single hospital or a set of hospitals in a given geographic area is the starting point of planning to fill the gap between the optimal and required rate of hospital surge capacity. The early discharge strategy rate can help disaster planners and managers to prepare for and respond to health problems [6, 7].

Children, as one of the most vulnerable groups are always a part of the disasters victims. However, they have often been overlooked and disregarded in disaster preparedness studies, including those on early inpatient discharge [8-13]. In one of the few studies available in this area, a five-level classification system of the risk of health-threatening events that may be experienced by inpatient pediatrics due to early discharge, was presented [14]. However, there have been few studies on examining the effect of early discharge of adult inpatients on increasing hospital surge capacity. A similar research is a study on Royal Darwin Hospital response to a marine accident in which by discharging 19 inpatients at least one day earlier than planned and discharging all patients earlier in the day, surge capacity was made available to accommodate all victims [15].

Since the decision-maker and the person responsible for the final discharge of inpatients in normal conditions is the physician, he or she is also the best person to decide on the early discharge (or not) of an inpatient at the time of disasters. Considering the importance of planning to increase the surge capacity for admission of pediatrics in disaster, this study aimed to determine the rate of increase in surge capacity created in the pediatric departments of the studied hospitals using early discharge strategy.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study. Study population consisted of all children (aged 1-14 years) admitted to general pediatric, pediatric emergency and pediatric internal medicine departments of four hospitals affiliated with Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS). No sampling was performed and the entire population were enrolled (census procedure). Unwilling subjects to participate in the study as well as those who were at their normal discharge day at the time of data collection were excluded from the study. Eventually, 207 samples were enrolled in the study. Study participants included children’s physicians and parents, too.

Since the comprehensive literature review did not suggest any appropriate tool for collecting data in this study, a researcher-made questionnaire was employed that consisted of two sections; in section one, first, the definition of early discharge strategy in disaster was given. Then a short disaster scenario was presented in the geographical area of the hospitals. Finally, physicians were asked to make a decision on whether the pediatric inpatients under their treatment should be discharged early or not by “yes” or “no” answers.

The second section covered 7 items measuring demographic characteristics of physicians (gender, age, work experience) and pediatric inpatients (gender, age, parents’ educational level, and family monthly income) which was completed by the parents of the study samples. To measure the validity of the questionnaire, its initial version was sent to four health professionals in disasters and emergency medicine and after receiving their opinions and applying proposed changes, its final version was sent back to the experts and got approved by them.

Considering that the patients’ condition may change at any time which may subsequently influence the decision of the physician regarding their early discharge, internal consistency of the first section of the questionnaire was not taken into consideration. For the second section, reliability was evaluated using test-retest technique and Pearson correlation test. The correlation coefficient between test-retest results was obtained as 0.91 (P≤0.01) which indicated an acceptable reliability.

Both parts of the questionnaire were completed after obtaining informed and written consent from participants and they were assured of confidentiality of their information. The relevant data were gathered by one trained person in four days during four consecutive weeks (one day per week) with direct referral to the hospitals. Descriptive statistics (mean [SD], and percentage) and nonparametric tests (Pearson correlation, Chi-square and Mann-Whitney tests) were used for data analysis. The significant level was set as α=0.01.

3. Results

According to the results shown in Table 1, the highest surge capacity created after early discharge is seen in Imam Reza Hospital (59.37%), and the lowest created surge capacity is related to Dr. Sheikh Hospital (48.21%). In total, at least 55% of the actual capacity (active beds) of the hospitals can be released during disasters by using the early discharge procedure to accommodate all victims of disasters.

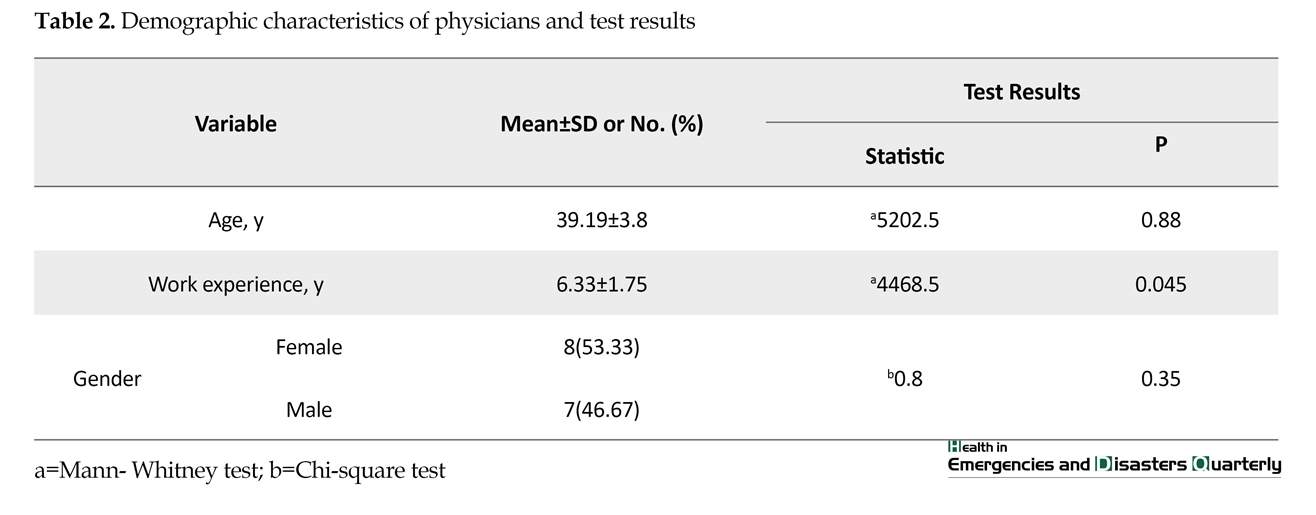

Table 2 presents demographic characteristics of physicians participated in the study and the statistical results of the difference in the demographic characteristics of the physicians between two groups of inpatients: Decided for early discharge, and not decided for early discharge. Based on the results, there is no statistically significant relationship between the demographic characteristics of the physicians and their decision on the early discharge of pediatric inpatients.

Table 3 presents the demographic characteristics of pediatric inpatients and the statistical results of the difference in the demographic characteristics and the decision on early discharge. Results shows no statistically significant relationship between the demographic characteristics of pediatric inpatients and the physicians’ decision on their early discharge.

4. Discussion

Results of this study on determining the rate of increase in surge capacity of four hospitals affiliated with MUMS by using early discharge policy, showed that this policy can free up to 55% of the surge capacity for the admission of pediatric victims in disasters. A similar study was conducted by Geravandi et al. [16] who examined the impact of implementing disaster preparedness program on increasing admission capacity of a non-governmental hospital in Ahvaz, Iran. The preparedness program at the hospital included staff training to manage crisis, improving the emergency room space, changes in organizational structure, and revision of some work guidelines. Their findings revealed a threefold increase in the admission capacity of the hospital departments after six months from the start of the program.

It is not clear whether early discharge strategies were included in their program or not; however, one of the goals pursued in the revision of the guidelines and work processes in the disasters preparedness plans is to facilitate the implementation of early discharge policy. Given this assumption, the findings of their study are in agreement with ours and both studies show a positive and significant effect of early discharge on increasing hospital surge capacity.

Geravandi et al. showed that with measures like creating physical capacity in the emergency department of the hospitals, the capacity for admission can be increased up to 2.6 times [17]. To some extent, this is consistent with

inding solutions to increase hospital surge capacity in disaster has always been one of the challenges of preparedness and response to disasters [1]. Early discharge of inpatients during disasters is among the most effective and fastest ways to create surge capacity [2-4]. Early inpatient discharge refers to the discharge of a hospitalized patient (before a disaster) from the hospital to increase the surge capacity, if there is no mortality risk for at least the next 72 hours ahead or possibility of serious complications arising from the discontinuation of the treatment process [5]. Awareness of the surge capacity that can be achieved by adopting in a single hospital or a set of hospitals in a given geographic area is the starting point of planning to fill the gap between the optimal and required rate of hospital surge capacity. The early discharge strategy rate can help disaster planners and managers to prepare for and respond to health problems [6, 7].

Children, as one of the most vulnerable groups are always a part of the disasters victims. However, they have often been overlooked and disregarded in disaster preparedness studies, including those on early inpatient discharge [8-13]. In one of the few studies available in this area, a five-level classification system of the risk of health-threatening events that may be experienced by inpatient pediatrics due to early discharge, was presented [14]. However, there have been few studies on examining the effect of early discharge of adult inpatients on increasing hospital surge capacity. A similar research is a study on Royal Darwin Hospital response to a marine accident in which by discharging 19 inpatients at least one day earlier than planned and discharging all patients earlier in the day, surge capacity was made available to accommodate all victims [15].

Since the decision-maker and the person responsible for the final discharge of inpatients in normal conditions is the physician, he or she is also the best person to decide on the early discharge (or not) of an inpatient at the time of disasters. Considering the importance of planning to increase the surge capacity for admission of pediatrics in disaster, this study aimed to determine the rate of increase in surge capacity created in the pediatric departments of the studied hospitals using early discharge strategy.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study. Study population consisted of all children (aged 1-14 years) admitted to general pediatric, pediatric emergency and pediatric internal medicine departments of four hospitals affiliated with Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS). No sampling was performed and the entire population were enrolled (census procedure). Unwilling subjects to participate in the study as well as those who were at their normal discharge day at the time of data collection were excluded from the study. Eventually, 207 samples were enrolled in the study. Study participants included children’s physicians and parents, too.

Since the comprehensive literature review did not suggest any appropriate tool for collecting data in this study, a researcher-made questionnaire was employed that consisted of two sections; in section one, first, the definition of early discharge strategy in disaster was given. Then a short disaster scenario was presented in the geographical area of the hospitals. Finally, physicians were asked to make a decision on whether the pediatric inpatients under their treatment should be discharged early or not by “yes” or “no” answers.

The second section covered 7 items measuring demographic characteristics of physicians (gender, age, work experience) and pediatric inpatients (gender, age, parents’ educational level, and family monthly income) which was completed by the parents of the study samples. To measure the validity of the questionnaire, its initial version was sent to four health professionals in disasters and emergency medicine and after receiving their opinions and applying proposed changes, its final version was sent back to the experts and got approved by them.

Considering that the patients’ condition may change at any time which may subsequently influence the decision of the physician regarding their early discharge, internal consistency of the first section of the questionnaire was not taken into consideration. For the second section, reliability was evaluated using test-retest technique and Pearson correlation test. The correlation coefficient between test-retest results was obtained as 0.91 (P≤0.01) which indicated an acceptable reliability.

Both parts of the questionnaire were completed after obtaining informed and written consent from participants and they were assured of confidentiality of their information. The relevant data were gathered by one trained person in four days during four consecutive weeks (one day per week) with direct referral to the hospitals. Descriptive statistics (mean [SD], and percentage) and nonparametric tests (Pearson correlation, Chi-square and Mann-Whitney tests) were used for data analysis. The significant level was set as α=0.01.

3. Results

According to the results shown in Table 1, the highest surge capacity created after early discharge is seen in Imam Reza Hospital (59.37%), and the lowest created surge capacity is related to Dr. Sheikh Hospital (48.21%). In total, at least 55% of the actual capacity (active beds) of the hospitals can be released during disasters by using the early discharge procedure to accommodate all victims of disasters.

Table 2 presents demographic characteristics of physicians participated in the study and the statistical results of the difference in the demographic characteristics of the physicians between two groups of inpatients: Decided for early discharge, and not decided for early discharge. Based on the results, there is no statistically significant relationship between the demographic characteristics of the physicians and their decision on the early discharge of pediatric inpatients.

Table 3 presents the demographic characteristics of pediatric inpatients and the statistical results of the difference in the demographic characteristics and the decision on early discharge. Results shows no statistically significant relationship between the demographic characteristics of pediatric inpatients and the physicians’ decision on their early discharge.

4. Discussion

Results of this study on determining the rate of increase in surge capacity of four hospitals affiliated with MUMS by using early discharge policy, showed that this policy can free up to 55% of the surge capacity for the admission of pediatric victims in disasters. A similar study was conducted by Geravandi et al. [16] who examined the impact of implementing disaster preparedness program on increasing admission capacity of a non-governmental hospital in Ahvaz, Iran. The preparedness program at the hospital included staff training to manage crisis, improving the emergency room space, changes in organizational structure, and revision of some work guidelines. Their findings revealed a threefold increase in the admission capacity of the hospital departments after six months from the start of the program.

It is not clear whether early discharge strategies were included in their program or not; however, one of the goals pursued in the revision of the guidelines and work processes in the disasters preparedness plans is to facilitate the implementation of early discharge policy. Given this assumption, the findings of their study are in agreement with ours and both studies show a positive and significant effect of early discharge on increasing hospital surge capacity.

Geravandi et al. showed that with measures like creating physical capacity in the emergency department of the hospitals, the capacity for admission can be increased up to 2.6 times [17]. To some extent, this is consistent with

our findings. Esmailian et al. [18] in a study with the aim of determining emergency response capacity of Al-Zahra Hospital in Isfahan, Iran reported that admission capacity in the hospital under normal conditions was 47 beds, and was increased to 74 beds in emergencies. In other words, the capacity increase was 57%. They did not specify percentage of the added capacity because of early discharge, although reverse triage was one of the strategies employed to increase the admission capacity.

Hence, their results are in line with ours. A study conducted in the USA on the effect of reverse triage on creation of surge capacity in a pediatric hospital by Kelen et al. [19], reported that with reverse triage (early discharge), the surge capacity can be increased up to 23%. This is far less than the average surge increase reported in our study (55. 46%). The reason for this inconsistency of findings can be due to the difference in the type of hospitals and that the findings in the descriptive and analytical cross-sectional studies depend on the time and place of the study.

In the current study, most of the study hospitals were non-specialized pediatric hospital, while the study of Kelen et al. was conducted in a specialized pediatric hospital. Usually, children admitted to a specialized pediatric hospital, are in a worse situation in terms of clinical and general conditions and are less likely to be candidate for early discharge, in comparison with children admitted to other hospitals. Findings of Van Cleve et al. [20] also are in agreement with this theory. In their study, the increase in surge capacity in a specialized pediatric hospital created by early discharge policy in response to pandemic H1N1 influenza was reported as 20.4% which is less than the increase rate reported in the current study.

5. Conclusion

In sum early discharge of pediatric inpatients can be considered as a useful strategy for increasing hospital surge capacity in disasters. The findings of this study can help planners and contributors of health care provide better health care and accommodation for a large number of injured children in disasters.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (code: 950473).

One of the limitations of this research was the unwillingness of some physicians to participate in the study, but after explaining about the questionnaire as well as the benefits and importance of research findings, they agreed to participate in our investigation.

Funding

This study was funded and supported by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest, or non- financial interest in the subject matter or materials dismissed in this manuscript.

References

Hence, their results are in line with ours. A study conducted in the USA on the effect of reverse triage on creation of surge capacity in a pediatric hospital by Kelen et al. [19], reported that with reverse triage (early discharge), the surge capacity can be increased up to 23%. This is far less than the average surge increase reported in our study (55. 46%). The reason for this inconsistency of findings can be due to the difference in the type of hospitals and that the findings in the descriptive and analytical cross-sectional studies depend on the time and place of the study.

In the current study, most of the study hospitals were non-specialized pediatric hospital, while the study of Kelen et al. was conducted in a specialized pediatric hospital. Usually, children admitted to a specialized pediatric hospital, are in a worse situation in terms of clinical and general conditions and are less likely to be candidate for early discharge, in comparison with children admitted to other hospitals. Findings of Van Cleve et al. [20] also are in agreement with this theory. In their study, the increase in surge capacity in a specialized pediatric hospital created by early discharge policy in response to pandemic H1N1 influenza was reported as 20.4% which is less than the increase rate reported in the current study.

5. Conclusion

In sum early discharge of pediatric inpatients can be considered as a useful strategy for increasing hospital surge capacity in disasters. The findings of this study can help planners and contributors of health care provide better health care and accommodation for a large number of injured children in disasters.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (code: 950473).

One of the limitations of this research was the unwillingness of some physicians to participate in the study, but after explaining about the questionnaire as well as the benefits and importance of research findings, they agreed to participate in our investigation.

Funding

This study was funded and supported by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest, or non- financial interest in the subject matter or materials dismissed in this manuscript.

References

- Abolghasem Gorgi H, Jafari M, Shabanikiya H, Seyedin H, Rahimi A, Vafaee-Najar A. Hospital surge capacity in disasters in a developing country: Challenges and strategies. Trauma Monthly. 2017; 22(5):e59238. [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.59238]

- Koenig K, Schultz CH. Surge capacity disaster medicine: Comprehensive principles and practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- Pollaris G, Sabbe M. Reverse triage: More than just another method. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016; 23(4):240-7. [DOI:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000339] [PMID]

- Schull MJ, Stukel TA, Vermeulen MJ, Gattmann A, Zwarenstein M. Surge capacity associated with restrictions on nonurgent hospital utilization and expected admissions during an influenza pandemic: lessons from the Toronto severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006; 13(11):1228-31. [DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2006.04.011] [PMID]

- Kelen GD, Kraus CK, McCarthy MS, Bass PE, Hsu EB, Li PG, et al. Inpatient disposition classification for the creation of hospital surge capacity: A multiphase study. Lancet. 2006. 368(9551):1984-90. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69808-5]

- Fuzak JK, Elkon BD, Hampers LC, Polage KJ, Milton JD, Powers LK, et al. Mass transfer of pediatric tertiary care hospital inpatients to a new location in under 12 hours: Lessons learned and implications for disaster preparedness. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2010; 157(1):138-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.047] [PMID]

- Shabanikiya H, Gorgi HA, Seyedin H, Jafari M. Assessment of hospital management and surge capacity in disasters. Trauma Monthly. 2016; 21(2):e30277. [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.30277] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Allen GM, Parrillo SJ, Will J, Mohr JA. Principles of disaster planning for the pediatric population. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2007; 22(6):536-40. [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X00005392]

- Antommaria AHM, Powell T, Miller JE, Christian MD. Ethical issues in pediatric emergency mass critical care. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2011; 12(6):S163-8. [DOI:10.1097/PCC.0b013e318234a88b] [PMID]

- Baren J, Rothrock S, Brennan J, Brown L. Pediatric emergency medicine. Amesterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008.

- Gorelick M, Alessandrini EA, Cronan K, Shults J. Revised Pediatric Emergency Assessment Tool (RePEAT): A severity index for pediatric emergency care. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007; 14(4):316-23. [DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.015] [PMID]

- Horeczko T, Enriquez B, McGrath EN, Gausche-Hill M, Lewis RJ. The pediatric assessment triangle: Accuracy of its application by nurses in the triage of children. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2013; 39(2):182-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jen.2011.12.020] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kanter RK. Strategies to improve pediatric disaster surge response: Potential mortality reduction and tradeoffs. Critical Care Medicine. 2007; 35(12):2837-42. [DOI:10.1097/00003246-200712000-00024] [PMID]

- Kelen GD, Sauer L, Clattenburg E, Lewis-Newby M. Pediatric disposition classification (reverse triage) system to create surge capacity. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2015; 9(3):283-90. [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2015.27] [PMID]

- Satterthwaite PS, Atkinson CJ. Using ‘reverse triage’ to create hospital surge capacity: Royal Darwin hospital’s response to the ashmore reef disaster. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2012; 29(2):160-2. [DOI:10.1136/emj.2010.098087] [PMID]

- Geravandi S, Saidemehr S, Mohammadi MJ. [Role of increased capacity of emergency department in injury admissions during disasters (Persian)]. The Journal of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 20(1):75-9.

- Geravandi S, Soltani F, Mohammadi M, Salmanzadeh S, Shirali S, Shahriari A, et al . [The effects of increasing the capacity of admission in emergency ward in increasing the rate of patient acceptance at the time of crisis (Persian)]. Armaghan-e-Danesh. 2016; 20(12):1057-69.

- Esmailian M, Salehnia MH, Hasan Sh. Assessment of emergency department response capacity in the face of crisis; A Brief Report. Iranian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016; 3(4):154-8.

- Kelen G, Troncoso R, Trebach J, Levin S, Cole G, Delaney CM, et al. Effect of reverse triage on creation of surge capacity in a pediatric hospital. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017; 171(4):e164829. [DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4829]

- Van Cleve WC, Hagan P, Lozano P, Mangione-Smith R. Investigating a pediatric hospital’s response to an inpatient census surge during the 2009 H1N1influenza pandemic. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2011; 37(8):376-82. [DOI:10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37048-1]

Type of article: Case Report |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2017/12/25 | Accepted: 2018/04/5 | Published: 2018/07/1

Received: 2017/12/25 | Accepted: 2018/04/5 | Published: 2018/07/1

References

1. Abolghasem Gorgi H, Jafari M, Shabanikiya H, Seyedin H, Rahimi A, Vafaee-Najar A. Hospital surge capacity in disasters in a developing country: Challenges and strategies. Trauma Monthly. 2017; 22(5):e59238. [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.59238] [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.59238]

2. Koenig K, Schultz CH. Surge capacity disaster medicine: Comprehensive principles and practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

3. Pollaris G, Sabbe M. Reverse triage: More than just another method. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016; 23(4):240-7. [DOI:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000339] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000339]

4. Schull MJ, Stukel TA, Vermeulen MJ, Gattmann A, Zwarenstein M. Surge capacity associated with restrictions on nonurgent hospital utilization and expected admissions during an influenza pandemic: lessons from the Toronto severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006; 13(11):1228-31. [DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2006.04.011] [PMID] [DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2006.04.011]

5. Kelen GD, Kraus CK, McCarthy MS, Bass PE, Hsu EB, Li PG, et al. Inpatient disposition classification for the creation of hospital surge capacity: A multiphase study. Lancet. 2006. 368(9551):1984-90. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69808-5] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69808-5]

6. Fuzak JK, Elkon BD, Hampers LC, Polage KJ, Milton JD, Powers LK, et al. Mass transfer of pediatric tertiary care hospital inpatients to a new location in under 12 hours: Lessons learned and implications for disaster preparedness. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2010; 157(1):138-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.047] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.047]

7. Shabanikiya H, Gorgi HA, Seyedin H, Jafari M. Assessment of hospital management and surge capacity in disasters. Trauma Monthly. 2016; 21(2):e30277. [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.30277] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.30277]

8. Allen GM, Parrillo SJ, Will J, Mohr JA. Principles of disaster planning for the pediatric population. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2007; 22(6):536-40. [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X00005392] [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X00005392]

9. Antommaria AHM, Powell T, Miller JE, Christian MD. Ethical issues in pediatric emergency mass critical care. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2011; 12(6):S163-8. [DOI:10.1097/PCC.0b013e318234a88b] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/PCC.0b013e318234a88b]

10. Baren J, Rothrock S, Brennan J, Brown L. Pediatric emergency medicine. Amesterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008.

11. Gorelick M, Alessandrini EA, Cronan K, Shults J. Revised Pediatric Emergency Assessment Tool (RePEAT): A severity index for pediatric emergency care. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007; 14(4):316-23. [DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.015] [PMID] [DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.015]

12. Horeczko T, Enriquez B, McGrath EN, Gausche-Hill M, Lewis RJ. The pediatric assessment triangle: Accuracy of its application by nurses in the triage of children. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2013; 39(2):182-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jen.2011.12.020] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1016/j.jen.2011.12.020]

13. Kanter RK. Strategies to improve pediatric disaster surge response: Potential mortality reduction and tradeoffs. Critical Care Medicine. 2007; 35(12):2837-42. [DOI:10.1097/00003246-200712000-00024] [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/00003246-200712000-00024]

14. Kelen GD, Sauer L, Clattenburg E, Lewis-Newby M. Pediatric disposition classification (reverse triage) system to create surge capacity. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2015; 9(3):283-90. [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2015.27] [PMID] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2015.27]

15. Satterthwaite PS, Atkinson CJ. Using 'reverse triage' to create hospital surge capacity: Royal Darwin hospital's response to the ashmore reef disaster. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2012; 29(2):160-2. [DOI:10.1136/emj.2010.098087] [PMID] [DOI:10.1136/emj.2010.098087]

16. Geravandi S, Saidemehr S, Mohammadi MJ. [Role of increased capacity of emergency department in injury admissions during disasters (Persian)]. The Journal of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 20(1):75-9.

17. Geravandi S, Soltani F, Mohammadi M, Salmanzadeh S, Shirali S, Shahriari A, et al . [The effects of increasing the capacity of admission in emergency ward in increasing the rate of patient acceptance at the time of crisis (Persian)]. Armaghan-e-Danesh. 2016; 20(12):1057-69.

18. Esmailian M, Salehnia MH, Hasan Sh. Assessment of emergency department response capacity in the face of crisis; A Brief Report. Iranian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016; 3(4):154-8.

19. Kelen G, Troncoso R, Trebach J, Levin S, Cole G, Delaney CM, et al. Effect of reverse triage on creation of surge capacity in a pediatric hospital. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017; 171(4):e164829. [DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4829] [DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4829]

20. Van Cleve WC, Hagan P, Lozano P, Mangione-Smith R. Investigating a pediatric hospital's response to an inpatient census surge during the 2009 H1N1influenza pandemic. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2011; 37(8):376-82. [DOI:10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37048-1] [DOI:10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37048-1]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |