Volume 4, Issue 1 (Autumn 2018)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2018, 4(1): 55-61 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Azizzadeh Forouzi M, Roudi RashtAbadi O S, Heidarzadeh A, Malkyan L, Ghazanfarabadi M. Studying the Relationship of Posttraumatic Growth With Religious Coping and Social Support Among Earthquake Victims of Bam. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2018; 4 (1) :55-61

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-189-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-189-en.html

Mansooreh Azizzadeh Forouzi1

, Om Salimeh Roudi RashtAbadi1

, Om Salimeh Roudi RashtAbadi1

, Aazam Heidarzadeh *2

, Aazam Heidarzadeh *2

, Lila Malkyan3

, Lila Malkyan3

, Mohammad Ghazanfarabadi3

, Mohammad Ghazanfarabadi3

, Om Salimeh Roudi RashtAbadi1

, Om Salimeh Roudi RashtAbadi1

, Aazam Heidarzadeh *2

, Aazam Heidarzadeh *2

, Lila Malkyan3

, Lila Malkyan3

, Mohammad Ghazanfarabadi3

, Mohammad Ghazanfarabadi3

1- Department of Medical Surgeical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery Razi, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

2- Department of Medical Surgeical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. ,heidarzadehaazam@yahoo.com

3- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran.

2- Department of Medical Surgeical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. ,

3- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 578 kb]

(1880 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5779 Views)

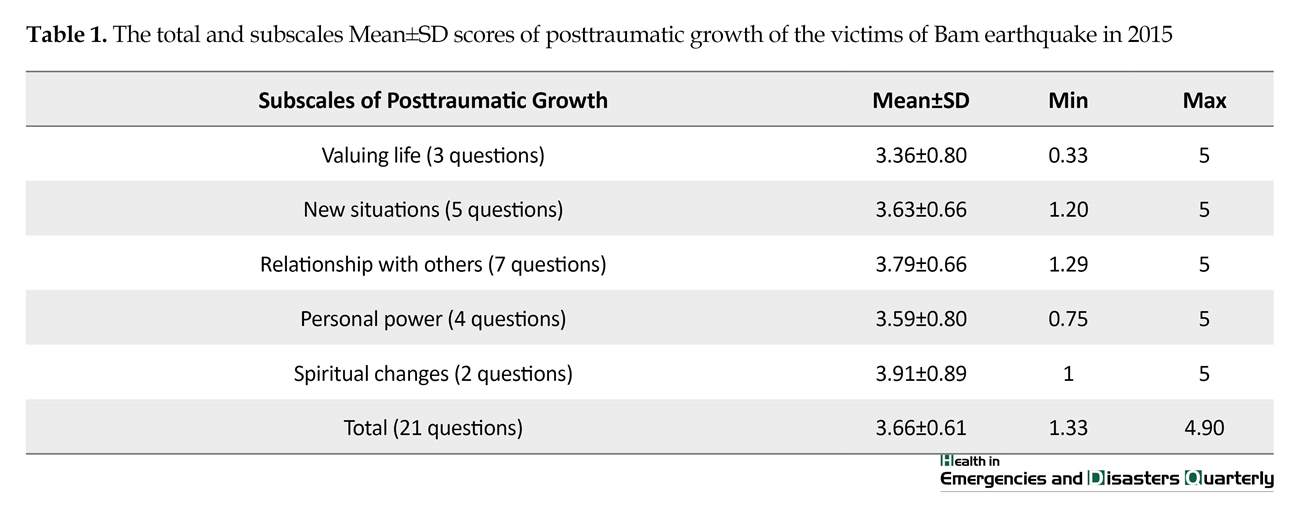

Their total Mean±SD of posttraumatic growth score was 3.66±0.61 and between the subscales, the highest Mean±SD score belonged to spiritual changes and the lowest Mean±SD score belonged to valuing life (Table 1). Furthermore, results of religious compatibility showed that the total Mean±SD of religious compatibility was 3.53±0.54 and the highest Mean±SD score belonged to the subscale of religious performance and the lowest Mean±SD score belonged to the subscale of negative emotions toward God (Table 2). Additionally, the Mean±SD score of perceived social support was 5.37±1.24 with a minimum of 1.58 and a maximum of 7.

The correlation between the total score of posttraumatic growth with the total score of religious compatibility was moderately significant and positive but its correlation with age and the number of children was weakly significant and positive. In addition, there was a weak significant and positive correlation between the score of compatibility with age and the number of children. Moreover, the correlation between the total score of posttraumatic growth with the total score of perceived social support was moderately significant and positive and its correlation with age and the number of children was weakly significant and positive (Table 3).

4. Discussion

One of the raised issues in the field of health psychology is evaluating the positive effects of psychological traumas on people who encountered disastrous events and determining the facilitating variables for these positive changes. Results of the present study showed that the Mean±SD of posttraumatic growth was 3.66±0.61 and among the items, the highest Mean±SD score belonged to spiritual changes and the lowest Mean±SD score belonged to valuing life.

In this regard, Heidarzadeh et al. conducted a study to evaluate the aspects of posttraumatic growth among cancer survivors and reported that the Mean±SD score of posttraumatic growth among the participants was 68.68±14.7 and among all the aspects of posttraumatic growth, spirituality and relationship with others with Mean±SD scores of 7.63±2.13 and 25.03±4.9, respectively gained the highest Mean±SD scores [5]. However results of Morris et al. study showed that the highest mean scores of aspects of posttraumatic growth belonged to “appreciating life”, and then to “relationship with others”, toward “personal empowerment”, “new priorities”, “spirituality”, and “spiritual changes” which had the lowest mean score [22].

Probably the reason for this different results might be explained by the spiritual nature of the Iranian society. In such a spiritual society, it could be expected that after encountering a disastrous event, individuals would gain the highest growth in the aspect of spirituality. In addition, previous studies have shown that spirituality is one of the main strategies for coping with cancer in Iran [5].

Results of the present study also showed that the total Mean±SD score of religious compatibility was 3.53±0.54 and the highest and lowest mean scores among the aspects of religious compatibility respectively belonged to “religious performance”, and “negative emotions toward God”. Furthermore a significant positive correlation existed between the total score of posttraumatic growth and the total score of religious compatibility. In 2014, Garcia et al. conducted a study to evaluate the predictive role of religious compatibility in posttraumatic growth among earthquake victims in Chile and reported that a significant positive relation existed between posttraumatic growth with religious compatibility and mental support [17]. Similarly, the results of Danhauer et al. study showed that religious beliefs among cancer patients and their families is the strongest predictor of posttraumatic growth. Some researchers believed that strong religious beliefs would fasten the recovery path for patients with chronic diseases, because with the help of these beliefs in coping with tensions, patients would have more ability to achieve posttraumatic growth [18].

The results of Mardiah and Syahriati study showed that positive religious coping can predict posttraumatic growth. On the other hand, negative religious coping in both studies cannot predict posttraumatic growth [23]. In addition, based on Bosson et al. study on survivors of Hurricane Katrina, there was a relation between posttraumatic growth and different factors, including positive religious coping [24]. To explain these results it could be said that religious compatibility is defined as a search for the meaning of life with the help of spiritual methods during the time of tension. Religious compatibility includes application of cognitive strategies, religious-based behaviors, or religious methods for managing emotional stress or physical discomfort [12]. Therefore individuals with higher religious compatibility are able to feel positive perceptions from the encountered dangerous events or continue life constructively, despite all the damages or pains.

Evaluating the relation between posttraumatic growth and perceived social support showed a significant positive correlation between the total score of posttraumatic growth and perceived social support. Garcia, et al. study results indicate a positive and significant correlation between all aspects of posttraumatic growth with aspects of perceived social support; the strongest relation was between the aspects of social support and the aspect of interpersonal posttraumatic growth [17] which is in line with the present study. One of the reasons for this result might be that social support is considered as the strongest coping strategy to successfully and easily overcome stressful situations [15]. Results of Cryde et al. study show that competency beliefs is related to posttraumatic growth and a supportive social environment and ruminative thinking are associated with positive competency beliefs [25].

Another study also demonstrated a relationship between posttraumatic growth and social support in survivors of earthquake [26]. On the other hand, lack of social support is an important predictive factors for readmission to hospitals and mortality among cancer patients. Social support could affect individual’s cognitive evaluations and their beliefs about the world [27]. However, results of Alipore et al. indicate a significant relation between social support and posttraumatic growth in survivors of East Azerbaijan earthquake, but this relationship was adverse i.e., with increasing social support, the rate of posttraumatic growth decreases [28]. Thus, social support is recognized as an important factor in posttraumatic growth or improvement of posttraumatic stress disorder and survivors with lower levels of social support have reported more symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.

5. Conclusions

According to the results of the present study, the authorities should improve the quality of religious cares and social supports for individuals who have encountered natural disasters. In addition, results of the present study could provide appropriate information for policymakers to provide religious care and social support for people who have encountered any kind of crisis in their lives.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is adopted from a research project approved by the Ethics Committee with ethics code of IR.KMU.REC.1394.342 and was funded by Kerman University of Medical Sciences. Adequate level of confidentiality of the research data was observed. The participants voluntarily took part in the study and their responses were based on informed consent.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Researchers would like to appreciate the sincere cooperation of the participants despite their personal grieving.

Reference

Full-Text: (1807 Views)

1. Introduction

Because of its geographical and climatic variety, Iran is one of the most disaster-prone countries of the world. Natural disasters, for example earthquake, is an unexpected event that cause death and destruction to human life and properties, and the injured people without others’ assistance could not survive [1]. Iran stands the sixth in the ranking for natural disasters in the world and is located in the 10 top earthquake trigger zones. Approximately 69% of its lands lie over faults. During the past century, 20 earthquakes measuring above 6 on the Richter scale have been recorded leading to 500000 casualties [2]. The massive disastrous earthquake in the January 2004 in Bam, as a national catastrophe, involved the relief organizations and units, including mental health, with the challenge of what, how, when, and how much services should be provided and also how appropriate were those services compared to the needs of the victims [3].

Bayanzadeh et al. study reported that the prevalence of mental problems increased from 5.8% before Bam earthquake to 35% two months after the earthquake which was 6 times more. About 92.5% of people lost at least one of their family members in the earthquake. Physical disability increased from 10.2% before the earthquake to 22.6% two months after the earthquake [4]. Based on the conducted studies during the recent years, it seems that many survivors of the stressful events would experience positive psychological changes. This is called posttraumatic growth and is defined as experience or mental recognition of positive psychological changes caused by struggling with a stressful event [5, 6].

Posttraumatic growth mostly has five domains of “more appreciation for moments of life”, “more meaningful personal communications”, “recognition of personal unique abilities”, “changes in life priorities”, and “evolution of the spiritual aspect of life” [7]. This phenomenon has also been studied with other expressions such as “benefit finding”, “stress-related growth”, “flourishing”,“positive judgment power”, and “self-renovation” [8]. However, most of the researchers in this field would prefer the term “posttraumatic growth” to describe these positive changes [9, 10] .

Conducted studies on posttraumatic growth phenomenon have revealed that various personal, interpersonal, and social factors could affect it, including religious beliefs. Religion is defined as a system of symbols and signs that would help people to have a better understanding of their lives’ situations and provide a framework for understanding and interpreting the life-changing events [11]. Religious compatibility employs cognitive strategies, religious-based behaviors or religious methods for coping with emotional stress or physical discomfort [12]. Therefore, from psychological point of view, religious compatibility is helpful and presents ways for the individual to achieve mental, emotional relaxation [13].

Social support is another predictor of mental health. The concept of perceived social support describes support from individual’s evaluative-cognitive view of their environment and relationship with others. The theorists in the field of perceived social support have indicated that all of the individual’s relationships cannot be considered as social support. In other words, relationships are not the source of social support unless the individual use them as an available or appropriate source for resolving his or her needs [14]. Social support is recognized as the most powerful coping force to successfully and easily overcome stressful situations and control it [15]. By playing a mediator role between the stressful factors of life and occurrence of physical and mental problems and also strengthening individual’s cognition, social support would decrease the experienced tension, increase the rate of survival, and improve health situations which would eventually lead to improved quality of life [16].

Results of Garcia et al. study showed that all the aspects of posttraumatic growth had a positive significant relation with all the aspects of perceived social support [17]. Other conducted studies have evaluated the relation between posttraumatic growth and other fields. For example, Danhauer et al. revealed that religious beliefs among cancer patients and their families were the strongest predictive factor for posttraumatic growth [18]. Another study showed a significant relation between posttraumatic growth with avoidance attachment, stress-oriented coping strategy, and quality of life [19].

Considering the limited number of studies conducted in the field of posttraumatic growth and its related factors, the present study was conducted to evaluate the relation between posttraumatic growth with religious compatibility and perceived social support among earthquake victims of Bam in 2015. We hope that the results of this study would be helpful by providing appropriate strategies for improving the quality of religious care and social support in people who have struggled natural disasters. In addition, the results of the present study could provide appropriate information for policymakers to provide religious care and social support for people who have encountered any kind of crisis in their lives.

2. Materials and Methods

The present research was an analytic correlation study conducted to evaluate the relationship between posttraumatic growth with religious compatibility and social support among earthquake victims of Bam in 2015. The number of samples was calculated to be 230 of the Bam population using sample size formula. Sampling was conducted using randomized cluster method from 5 districts of Bam. After receiving the zip codes from the Bam postal office, the samples were selected from the first address of each zip code at each district and then sampling was started from the first house after taking their consent. The eligible person from the first house received the questionnaire and data gathering continued until completing the sample number. The inclusion criteria were being present in Bam at the time of the earthquake and lacking any history of psychological disorders (self-report).

To achieve the goals of the study, a 4-part questionnaire was used: 1. Demographic characteristics; 2. Posttraumatic growth; 3. Religious compatibility; and 4. Social support.

Demographic characteristics

This part contained the demographic characteristics of the participants including age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment status. In addition, some questions were asked to determine the religion of the participants. The questions such as “do you consider yourself a religious person?”, “is religion a source of power and calmness for you?”, “have religion helped you to overcome the post-earthquake situations?”, and “have religion helped your family members to overcome the post-earthquake situations?” along with a 11-point scoring scale from “not at all”, to “very much” were used to evaluate the religiosity of the participants and their mean scores were used for reporting the results [20].

Posttraumatic growth questionnaire:

It was developed by Tedeschil in 1996 to evaluate individual’s self-perception changes related to damaging incidents. This tool has 21 items and 5 dimensions that determines the level of psychological growth after encountering a stressful event (new situations, relationships with others, valuing life, personal power, and spiritual changes). It is scored based on a 6-point Likert-type scale and the score of 0 would be assigned to the first choice and the scores of 1 to 5 would respectively be assigned to the second to sixth choices. The total score ranges from 0 to 105; higher scores indicate more growth and lower scores indicate less growth. At this part, the mean score was also used for reporting the situation of posttraumatic growth. Psychometric evaluation of this tool has been performed by Heidarzadeh et al. and it has been standardized for the Iranian society. The Cronbach α coefficient for the entire questionnaire is 0.87 and for its subscales are between 0.57 and 0.87 [5].

Religious compatibility questionnaire

It was developed by Aflakseir and Coleman in 2011. This questionnaire has 22 items with a 5-point scoring scale from “not at all” to “very much” which would evaluate religious performance including positive and negative religious patterns in the form of 5 subscales. The total score of religious compatibility is obtained by summation of the mean scores of the 5 subscales. Internal consistency of this tool was evaluated by Rafiei et al. in 2011. The Cronbach α for “religious acts” was 0.89, for “benevolent evaluation” 0.79, for “negative emotions toward God” 0.79, for “active religious coping strategies” 0.72 and for “passive religious coping strategies” 0.79 [13].

Perceived social support questionnaire

It was developed by Zimet et al. in 1988. This scale has 12 items which would evaluate perceived social support by the individual from three sources of family, friends, and important people in life. Participants’ degree of agreement is measured by a 7-point Likert-type scale from completely agree (7 points) to completely disagree (1 point) and the mean score would be reported as the result. The validity of this scale was approved in Khalili et al. study which evaluated the validity and reliability of this questionnaire in Isfahan in 2011 and the reported Cronbach α for this tool was 0.71 [21].

The gathered data were fed into SPSS V. 18 and analyzed using central and dispersion indicators such as mean and standard deviation for estimating the score of each questionnaire and also using variance and t tests. The variance analysis and correlation coefficient were used for analysis of 3-state variables, 2-state variables and the relation between variables, respectively.

3. Results

Results of the present study showed that the Mean±SD age of the participants was 36.52±7.15 years with a minimum of 21 years and a maximum of 59 years. The Mean±SD number of their children was 1.46±1.15 with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 6. Most of the participants were women and married. Regarding the educational level, the lowest percentage belonged to illiterate and elementary school level groups. About 24.3% of the participants were housewives and 47% were employed or employee of higher education institutes. The lowest percentage of the participants (11.3%) was living alone and most of them (42.6%) were living with their spouses and children.

Posttraumatic growth mostly has five domains of “more appreciation for moments of life”, “more meaningful personal communications”, “recognition of personal unique abilities”, “changes in life priorities”, and “evolution of the spiritual aspect of life” [7]. This phenomenon has also been studied with other expressions such as “benefit finding”, “stress-related growth”, “flourishing”,“positive judgment power”, and “self-renovation” [8]. However, most of the researchers in this field would prefer the term “posttraumatic growth” to describe these positive changes [9, 10] .

Conducted studies on posttraumatic growth phenomenon have revealed that various personal, interpersonal, and social factors could affect it, including religious beliefs. Religion is defined as a system of symbols and signs that would help people to have a better understanding of their lives’ situations and provide a framework for understanding and interpreting the life-changing events [11]. Religious compatibility employs cognitive strategies, religious-based behaviors or religious methods for coping with emotional stress or physical discomfort [12]. Therefore, from psychological point of view, religious compatibility is helpful and presents ways for the individual to achieve mental, emotional relaxation [13].

Social support is another predictor of mental health. The concept of perceived social support describes support from individual’s evaluative-cognitive view of their environment and relationship with others. The theorists in the field of perceived social support have indicated that all of the individual’s relationships cannot be considered as social support. In other words, relationships are not the source of social support unless the individual use them as an available or appropriate source for resolving his or her needs [14]. Social support is recognized as the most powerful coping force to successfully and easily overcome stressful situations and control it [15]. By playing a mediator role between the stressful factors of life and occurrence of physical and mental problems and also strengthening individual’s cognition, social support would decrease the experienced tension, increase the rate of survival, and improve health situations which would eventually lead to improved quality of life [16].

Results of Garcia et al. study showed that all the aspects of posttraumatic growth had a positive significant relation with all the aspects of perceived social support [17]. Other conducted studies have evaluated the relation between posttraumatic growth and other fields. For example, Danhauer et al. revealed that religious beliefs among cancer patients and their families were the strongest predictive factor for posttraumatic growth [18]. Another study showed a significant relation between posttraumatic growth with avoidance attachment, stress-oriented coping strategy, and quality of life [19].

Considering the limited number of studies conducted in the field of posttraumatic growth and its related factors, the present study was conducted to evaluate the relation between posttraumatic growth with religious compatibility and perceived social support among earthquake victims of Bam in 2015. We hope that the results of this study would be helpful by providing appropriate strategies for improving the quality of religious care and social support in people who have struggled natural disasters. In addition, the results of the present study could provide appropriate information for policymakers to provide religious care and social support for people who have encountered any kind of crisis in their lives.

2. Materials and Methods

The present research was an analytic correlation study conducted to evaluate the relationship between posttraumatic growth with religious compatibility and social support among earthquake victims of Bam in 2015. The number of samples was calculated to be 230 of the Bam population using sample size formula. Sampling was conducted using randomized cluster method from 5 districts of Bam. After receiving the zip codes from the Bam postal office, the samples were selected from the first address of each zip code at each district and then sampling was started from the first house after taking their consent. The eligible person from the first house received the questionnaire and data gathering continued until completing the sample number. The inclusion criteria were being present in Bam at the time of the earthquake and lacking any history of psychological disorders (self-report).

To achieve the goals of the study, a 4-part questionnaire was used: 1. Demographic characteristics; 2. Posttraumatic growth; 3. Religious compatibility; and 4. Social support.

Demographic characteristics

This part contained the demographic characteristics of the participants including age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment status. In addition, some questions were asked to determine the religion of the participants. The questions such as “do you consider yourself a religious person?”, “is religion a source of power and calmness for you?”, “have religion helped you to overcome the post-earthquake situations?”, and “have religion helped your family members to overcome the post-earthquake situations?” along with a 11-point scoring scale from “not at all”, to “very much” were used to evaluate the religiosity of the participants and their mean scores were used for reporting the results [20].

Posttraumatic growth questionnaire:

It was developed by Tedeschil in 1996 to evaluate individual’s self-perception changes related to damaging incidents. This tool has 21 items and 5 dimensions that determines the level of psychological growth after encountering a stressful event (new situations, relationships with others, valuing life, personal power, and spiritual changes). It is scored based on a 6-point Likert-type scale and the score of 0 would be assigned to the first choice and the scores of 1 to 5 would respectively be assigned to the second to sixth choices. The total score ranges from 0 to 105; higher scores indicate more growth and lower scores indicate less growth. At this part, the mean score was also used for reporting the situation of posttraumatic growth. Psychometric evaluation of this tool has been performed by Heidarzadeh et al. and it has been standardized for the Iranian society. The Cronbach α coefficient for the entire questionnaire is 0.87 and for its subscales are between 0.57 and 0.87 [5].

Religious compatibility questionnaire

It was developed by Aflakseir and Coleman in 2011. This questionnaire has 22 items with a 5-point scoring scale from “not at all” to “very much” which would evaluate religious performance including positive and negative religious patterns in the form of 5 subscales. The total score of religious compatibility is obtained by summation of the mean scores of the 5 subscales. Internal consistency of this tool was evaluated by Rafiei et al. in 2011. The Cronbach α for “religious acts” was 0.89, for “benevolent evaluation” 0.79, for “negative emotions toward God” 0.79, for “active religious coping strategies” 0.72 and for “passive religious coping strategies” 0.79 [13].

Perceived social support questionnaire

It was developed by Zimet et al. in 1988. This scale has 12 items which would evaluate perceived social support by the individual from three sources of family, friends, and important people in life. Participants’ degree of agreement is measured by a 7-point Likert-type scale from completely agree (7 points) to completely disagree (1 point) and the mean score would be reported as the result. The validity of this scale was approved in Khalili et al. study which evaluated the validity and reliability of this questionnaire in Isfahan in 2011 and the reported Cronbach α for this tool was 0.71 [21].

The gathered data were fed into SPSS V. 18 and analyzed using central and dispersion indicators such as mean and standard deviation for estimating the score of each questionnaire and also using variance and t tests. The variance analysis and correlation coefficient were used for analysis of 3-state variables, 2-state variables and the relation between variables, respectively.

3. Results

Results of the present study showed that the Mean±SD age of the participants was 36.52±7.15 years with a minimum of 21 years and a maximum of 59 years. The Mean±SD number of their children was 1.46±1.15 with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 6. Most of the participants were women and married. Regarding the educational level, the lowest percentage belonged to illiterate and elementary school level groups. About 24.3% of the participants were housewives and 47% were employed or employee of higher education institutes. The lowest percentage of the participants (11.3%) was living alone and most of them (42.6%) were living with their spouses and children.

Their total Mean±SD of posttraumatic growth score was 3.66±0.61 and between the subscales, the highest Mean±SD score belonged to spiritual changes and the lowest Mean±SD score belonged to valuing life (Table 1). Furthermore, results of religious compatibility showed that the total Mean±SD of religious compatibility was 3.53±0.54 and the highest Mean±SD score belonged to the subscale of religious performance and the lowest Mean±SD score belonged to the subscale of negative emotions toward God (Table 2). Additionally, the Mean±SD score of perceived social support was 5.37±1.24 with a minimum of 1.58 and a maximum of 7.

The correlation between the total score of posttraumatic growth with the total score of religious compatibility was moderately significant and positive but its correlation with age and the number of children was weakly significant and positive. In addition, there was a weak significant and positive correlation between the score of compatibility with age and the number of children. Moreover, the correlation between the total score of posttraumatic growth with the total score of perceived social support was moderately significant and positive and its correlation with age and the number of children was weakly significant and positive (Table 3).

4. Discussion

One of the raised issues in the field of health psychology is evaluating the positive effects of psychological traumas on people who encountered disastrous events and determining the facilitating variables for these positive changes. Results of the present study showed that the Mean±SD of posttraumatic growth was 3.66±0.61 and among the items, the highest Mean±SD score belonged to spiritual changes and the lowest Mean±SD score belonged to valuing life.

In this regard, Heidarzadeh et al. conducted a study to evaluate the aspects of posttraumatic growth among cancer survivors and reported that the Mean±SD score of posttraumatic growth among the participants was 68.68±14.7 and among all the aspects of posttraumatic growth, spirituality and relationship with others with Mean±SD scores of 7.63±2.13 and 25.03±4.9, respectively gained the highest Mean±SD scores [5]. However results of Morris et al. study showed that the highest mean scores of aspects of posttraumatic growth belonged to “appreciating life”, and then to “relationship with others”, toward “personal empowerment”, “new priorities”, “spirituality”, and “spiritual changes” which had the lowest mean score [22].

Probably the reason for this different results might be explained by the spiritual nature of the Iranian society. In such a spiritual society, it could be expected that after encountering a disastrous event, individuals would gain the highest growth in the aspect of spirituality. In addition, previous studies have shown that spirituality is one of the main strategies for coping with cancer in Iran [5].

Results of the present study also showed that the total Mean±SD score of religious compatibility was 3.53±0.54 and the highest and lowest mean scores among the aspects of religious compatibility respectively belonged to “religious performance”, and “negative emotions toward God”. Furthermore a significant positive correlation existed between the total score of posttraumatic growth and the total score of religious compatibility. In 2014, Garcia et al. conducted a study to evaluate the predictive role of religious compatibility in posttraumatic growth among earthquake victims in Chile and reported that a significant positive relation existed between posttraumatic growth with religious compatibility and mental support [17]. Similarly, the results of Danhauer et al. study showed that religious beliefs among cancer patients and their families is the strongest predictor of posttraumatic growth. Some researchers believed that strong religious beliefs would fasten the recovery path for patients with chronic diseases, because with the help of these beliefs in coping with tensions, patients would have more ability to achieve posttraumatic growth [18].

The results of Mardiah and Syahriati study showed that positive religious coping can predict posttraumatic growth. On the other hand, negative religious coping in both studies cannot predict posttraumatic growth [23]. In addition, based on Bosson et al. study on survivors of Hurricane Katrina, there was a relation between posttraumatic growth and different factors, including positive religious coping [24]. To explain these results it could be said that religious compatibility is defined as a search for the meaning of life with the help of spiritual methods during the time of tension. Religious compatibility includes application of cognitive strategies, religious-based behaviors, or religious methods for managing emotional stress or physical discomfort [12]. Therefore individuals with higher religious compatibility are able to feel positive perceptions from the encountered dangerous events or continue life constructively, despite all the damages or pains.

Evaluating the relation between posttraumatic growth and perceived social support showed a significant positive correlation between the total score of posttraumatic growth and perceived social support. Garcia, et al. study results indicate a positive and significant correlation between all aspects of posttraumatic growth with aspects of perceived social support; the strongest relation was between the aspects of social support and the aspect of interpersonal posttraumatic growth [17] which is in line with the present study. One of the reasons for this result might be that social support is considered as the strongest coping strategy to successfully and easily overcome stressful situations [15]. Results of Cryde et al. study show that competency beliefs is related to posttraumatic growth and a supportive social environment and ruminative thinking are associated with positive competency beliefs [25].

Another study also demonstrated a relationship between posttraumatic growth and social support in survivors of earthquake [26]. On the other hand, lack of social support is an important predictive factors for readmission to hospitals and mortality among cancer patients. Social support could affect individual’s cognitive evaluations and their beliefs about the world [27]. However, results of Alipore et al. indicate a significant relation between social support and posttraumatic growth in survivors of East Azerbaijan earthquake, but this relationship was adverse i.e., with increasing social support, the rate of posttraumatic growth decreases [28]. Thus, social support is recognized as an important factor in posttraumatic growth or improvement of posttraumatic stress disorder and survivors with lower levels of social support have reported more symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.

5. Conclusions

According to the results of the present study, the authorities should improve the quality of religious cares and social supports for individuals who have encountered natural disasters. In addition, results of the present study could provide appropriate information for policymakers to provide religious care and social support for people who have encountered any kind of crisis in their lives.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is adopted from a research project approved by the Ethics Committee with ethics code of IR.KMU.REC.1394.342 and was funded by Kerman University of Medical Sciences. Adequate level of confidentiality of the research data was observed. The participants voluntarily took part in the study and their responses were based on informed consent.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Researchers would like to appreciate the sincere cooperation of the participants despite their personal grieving.

Reference

- Ajami S. A comparative study on the Earthquake Information Management Systems (EIMS) in India, Afghanistan and Iran. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2012; 1:27. [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.99963] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Azami-Aghdash S, Kazemi A, Ziapour B. Crisis management aspects of Bam catastrophic earthquake. Health Promotion Perspectives. 2015; 5(1):3-13. [DOI:10.15171/hpp.2015.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bolhari J, Chime N. Mental health intervention in bam earthquake crisis: A qualitative study. Tehran University Medical Journal TUMS Publications. 2008; 65(13):7-13.

- Akbar B, Yadollah E, Sam-E Aram E, Forouzan S, Mostafa E. [An investigation about the living conditions of Bam earthquake survivals (Persian)]. Social Welfare. 2004; 4(13):113-32.

- Heidarzadeh M, Rassouli M, Shahbolaghi F, Alavi Majd H, Mirzaei H, Tahmasebi M. [Assessing dimensions of posttraumatic growth of cancer in survived patients (Persian)]. Holistic Nursing and Midwifery Journal. 2015; 25(2):33-41.

- Tedeschi RG, Tedeschi RG, Park CL, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Positive changes in the aftermath of crisis. Abingdon: Routledge; 1998.

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004; 15(1):1-18. [DOI:10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01]

- Parry C, Chesler MA. Thematic evidence of psychosocial thriving in childhood cancer survivors. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15(8):1055-73. [DOI:10.1177/1049732305277860] [PMID]

- Jayawickreme E, Blackie LE. Post‐traumatic growth as positive personality change: Evidence, controversies and future directions. European Journal of Personality. 2014; 28(4):312-31. [DOI:10.1002/per.1963]

- Sumalla EC, Ochoa C, Blanco I. Posttraumatic growth in cancer: Reality or illusion? Clinical Psychology Review. 2009; 29(1):24-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.006] [PMID]

- Ward TG. Religious coping and posttraumatic growth among children of parental cancer. Virginia: Regent University; 2014.

- Asayesh H, Zamanian H, Mirgheisari A. Spiritual well-being and religious coping strategies among hemodialysis patients. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2013; 1(1):48-54.

- Aflakseir A, Coleman PG. Initial development of the iranian religious coping scale. Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2011; 6(1):44-61. [DOI:10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0006.104]

- Marashian F, Esmaili E. [The relationship between spiritual coping and life satisfaction with mental health among the students of Islamic Azad University of Ahvaz (Persian)]. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2012; 7(24):85-98.

- Bayrami M, Zahmatyar H, Bahadori Kj. [Prediction strategies To coping with stress in the pregnancy women with first experience on the based factors hardiness and social support (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research. 2013; 7(27):1-9.

- Lotfi Kf, Taheri A, Mirzaee H, Masoudi Mz. [Relationship between social support and self-esteem with depression and anxiety in cancer patients (Persian)]. Journal of New Findings in Psychology (Social Psychology). 2013; 7(25):101-15.

- García FE, Páez-Rovira D, Zurtia GC, Martel HN, Reyes AR. Religious coping, social support and subjective severity as predictors of posttraumatic growth in people affected by the earthquake in Chile on 27/2/2010. Religions. 2014; 5(4):1132-45. [DOI:10.3390/rel5041132]

- Danhauer SC, Russell GB, Tedeschi RG, Jesse MT, Vishnevsky T, Daley K, et al. A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic growth in adult patients undergoing treatment for acute Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2013; 20(1):13-24. [DOI:10.1007/s10880-012-9304-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mehrabi H, Noroozi S, Mirzaei Gr, Kazemi H. [An investigation the relationship between post traumatic growth and attachment styles, stress coping styles & quality of life in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Nurse and Physician Within War. 2014; 2(4):153-61.

- Ghaedi G, Yaaghoobi H. [A study on the relationship between different dimensions of perceived social support and different aspects of wellbeing (Persian)]. Armaghan-e-Danesh. 2008; 13(2):69-81.

- Khalili F, Sam S, Shariferad G, Hassanzadeh A, Kazemi M. [The relationship between perceived social support and social health of elderly (Persian)]. Health System Research. 2011; 7(6):1-9.

- Morris BA, Shakespeare-Finch J, Scott JL. Posttraumatic growth after cancer: The importance of health-related benefits and newfound compassion for others. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012; 20(4):749-56. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1143-7] [PMID]

- Mardiah A, Syahriati E. [Can religious coping predict posttraumatic growth (Persian)]. TARBIYA: Journal of Education in Muslim Society. 2016; 2(1):61-9.

- Bosson JV, Kelley ML, Jones GN. Deliberate cognitive processing mediates the relation between positive religious coping and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2012; 17(5):439-51. [DOI:10.1080/15325024.2011.650131]

- Cryder CH, Kilmer RP, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. An exploratory study of posttraumatic growth in children following a natural disaster. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006; 76(1):65-9. [DOI:10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.65] [PMID]

- García FE, Cova F, Rincón P, Vázquez C, Páez D. Coping, rumination and posttraumatic growth in people affected by an earthquake. Psicothema. 2016; 28(1):59-65.

- Morris B, Chambers SK, Campbell M, Dwyer M, Dunn J. Motorcycles and breast cancer: The influence of peer support and challenge on distress and posttraumatic growth. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012; 20(8):1849-58. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1287-5] [PMID]

- Mardani M, Alipour F, Qaderi R, Sabzi Khoshnam M. The status of posttraumatic growth in earthquake survivors, three years after the earthquake in East Azerbaijan. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly. 2017; 2(3):155-60. [DOI:10.18869/nrip.hdq.2.3.155]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2018/02/10 | Accepted: 2018/07/17 | Published: 2018/10/1

Received: 2018/02/10 | Accepted: 2018/07/17 | Published: 2018/10/1

References

1. Ajami S. A comparative study on the Earthquake Information Management Systems (EIMS) in India, Afghanistan and Iran. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2012; 1:27. [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.99963] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.99963]

2. Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Azami-Aghdash S, Kazemi A, Ziapour B. Crisis management aspects of Bam catastrophic earthquake. Health Promotion Perspectives. 2015; 5(1):3-13. [DOI:10.15171/hpp.2015.002] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.15171/hpp.2015.002]

3. Bolhari J, Chime N. Mental health intervention in bam earthquake crisis: A qualitative study. Tehran University Medical Journal TUMS Publications. 2008; 65(13):7-13.

4. Akbar B, Yadollah E, Sam-E Aram E, Forouzan S, Mostafa E. [An investigation about the living conditions of Bam earthquake survivals (Persian)]. Social Welfare. 2004; 4(13):113-32.

5. Heidarzadeh M, Rassouli M, Shahbolaghi F, Alavi Majd H, Mirzaei H, Tahmasebi M. [Assessing dimensions of posttraumatic growth of cancer in survived patients (Persian)]. Holistic Nursing and Midwifery Journal. 2015; 25(2):33-41.

6. Tedeschi RG, Tedeschi RG, Park CL, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Positive changes in the aftermath of crisis. Abingdon: Routledge; 1998.

7. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004; 15(1):1-18. [DOI:10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01] [DOI:10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01]

8. Parry C, Chesler MA. Thematic evidence of psychosocial thriving in childhood cancer survivors. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15(8):1055-73. [DOI:10.1177/1049732305277860] [PMID] [DOI:10.1177/1049732305277860]

9. Jayawickreme E, Blackie LE. Post‐traumatic growth as positive personality change: Evidence, controversies and future directions. European Journal of Personality. 2014; 28(4):312-31. [DOI:10.1002/per.1963] [DOI:10.1002/per.1963]

10. Sumalla EC, Ochoa C, Blanco I. Posttraumatic growth in cancer: Reality or illusion? Clinical Psychology Review. 2009; 29(1):24-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.006] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.006]

11. Ward TG. Religious coping and posttraumatic growth among children of parental cancer. Virginia: Regent University; 2014.

12. Asayesh H, Zamanian H, Mirgheisari A. Spiritual well-being and religious coping strategies among hemodialysis patients. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2013; 1(1):48-54.

13. Aflakseir A, Coleman PG. Initial development of the iranian religious coping scale. Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2011; 6(1):44-61. [DOI:10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0006.104] [DOI:10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0006.104]

14. Marashian F, Esmaili E. [The relationship between spiritual coping and life satisfaction with mental health among the students of Islamic Azad University of Ahvaz (Persian)]. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2012; 7(24):85-98.

15. Bayrami M, Zahmatyar H, Bahadori Kj. [Prediction strategies To coping with stress in the pregnancy women with first experience on the based factors hardiness and social support (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research. 2013; 7(27):1-9.

16. Lotfi Kf, Taheri A, Mirzaee H, Masoudi Mz. [Relationship between social support and self-esteem with depression and anxiety in cancer patients (Persian)]. Journal of New Findings in Psychology (Social Psychology). 2013; 7(25):101-15.

17. García FE, Páez-Rovira D, Zurtia GC, Martel HN, Reyes AR. Religious coping, social support and subjective severity as predictors of posttraumatic growth in people affected by the earthquake in Chile on 27/2/2010. Religions. 2014; 5(4):1132-45. [DOI:10.3390/rel5041132] [DOI:10.3390/rel5041132]

18. Danhauer SC, Russell GB, Tedeschi RG, Jesse MT, Vishnevsky T, Daley K, et al. A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic growth in adult patients undergoing treatment for acute Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2013; 20(1):13-24. [DOI:10.1007/s10880-012-9304-5] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1007/s10880-012-9304-5]

19. Mehrabi H, Noroozi S, Mirzaei Gr, Kazemi H. [An investigation the relationship between post traumatic growth and attachment styles, stress coping styles & quality of life in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Nurse and Physician Within War. 2014; 2(4):153-61.

20. Ghaedi G, Yaaghoobi H. [A study on the relationship between different dimensions of perceived social support and different aspects of wellbeing (Persian)]. Armaghan-e-Danesh. 2008; 13(2):69-81.

21. Khalili F, Sam S, Shariferad G, Hassanzadeh A, Kazemi M. [The relationship between perceived social support and social health of elderly (Persian)]. Health System Research. 2011; 7(6):1-9.

22. Morris BA, Shakespeare-Finch J, Scott JL. Posttraumatic growth after cancer: The importance of health-related benefits and newfound compassion for others. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012; 20(4):749-56. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1143-7] [PMID] [DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1143-7]

23. Mardiah A, Syahriati E. [Can religious coping predict posttraumatic growth (Persian)]. TARBIYA: Journal of Education in Muslim Society. 2016; 2(1):61-9. [DOI:10.15408/tjems.v2i1.1741]

24. Bosson JV, Kelley ML, Jones GN. Deliberate cognitive processing mediates the relation between positive religious coping and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2012; 17(5):439-51. [DOI:10.1080/15325024.2011.650131] [DOI:10.1080/15325024.2011.650131]

25. Cryder CH, Kilmer RP, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. An exploratory study of posttraumatic growth in children following a natural disaster. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006; 76(1):65-9. [DOI:10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.65] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.65]

26. García FE, Cova F, Rincón P, Vázquez C, Páez D. Coping, rumination and posttraumatic growth in people affected by an earthquake. Psicothema. 2016; 28(1):59-65. [PMID]

27. Morris B, Chambers SK, Campbell M, Dwyer M, Dunn J. Motorcycles and breast cancer: The influence of peer support and challenge on distress and posttraumatic growth. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012; 20(8):1849-58. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1287-5] [PMID] [DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1287-5]

28. Mardani M, Alipour F, Qaderi R, Sabzi Khoshnam M. The status of posttraumatic growth in earthquake survivors, three years after the earthquake in East Azerbaijan. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly. 2017; 2(3):155-60. [DOI:10.18869/nrip.hdq.2.3.155] [DOI:10.18869/nrip.hdq.2.3.155]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |