Volume 9, Issue 1 (Autumn 2023)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2023, 9(1): 7-22 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hamedanchi A, Khankeh H R, Abolfathi Momtaz Y, Zanjari N, Saatchi M, Ramezani T et al . An Integrative Review of the Psychosocial Impacts of COVID-19 on Frail Older Adults: Lessons to Be Learned in Pandemics. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2023; 9 (1) :7-22

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-524-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-524-en.html

Arya Hamedanchi1

, Hamid Reza Khankeh2

, Hamid Reza Khankeh2

, Yadollah Abolfathi Momtaz1

, Yadollah Abolfathi Momtaz1

, Nasibeh Zanjari1

, Nasibeh Zanjari1

, Mohammad Saatchi2

, Mohammad Saatchi2

, Tahereh Ramezani1

, Tahereh Ramezani1

, Ahmad Delbari *3

, Ahmad Delbari *3

, Hamid Reza Khankeh2

, Hamid Reza Khankeh2

, Yadollah Abolfathi Momtaz1

, Yadollah Abolfathi Momtaz1

, Nasibeh Zanjari1

, Nasibeh Zanjari1

, Mohammad Saatchi2

, Mohammad Saatchi2

, Tahereh Ramezani1

, Tahereh Ramezani1

, Ahmad Delbari *3

, Ahmad Delbari *3

1- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Health in Emergency and Disaster Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,ahmad_1128@yahoo.com

2- Health in Emergency and Disaster Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 1590 kb]

(809 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1954 Views)

Full-Text: (503 Views)

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought numerous negative consequences for older adults. The disease has caused additional complications, morbidity, and mortality, particularly in those older adults with underlying diseases [1]. Besides the medical impacts of pathogens, COVID-19 has devastating psychological and social impacts on the general health of older adults [2]. During the pandemic, older adults exhibit higher levels of anxiety, depression, interpersonal conflicts, and social isolation but lower levels of well-being [3, 4, 5, 6]. Evidence suggests that more than 75% of deaths caused by COVID-19 occurred in the age group of 65 years old and over [7]. In addition, higher mortality rates have been reported in frail people [8].Therefore, it has been recommended to take preventive interventions and more targeted approaches to prioritize older adults with comorbidities [9].

Frailty is one of the predisposing factors in older adults, which can increase the prevalence of diseases and incidents among them. As per Xue’s (2011) definition, frailty is “a clinically recognizable state of increased vulnerability resulting from aging-associated decline in reserve and functions across multiple physiologic systems such that the ability to cope with everyday or acute stressors is comprised” [10]. The prevalence of infectious diseases is also remarkably high among frail people [11]. Their access to health services might be difficult due to physical or mental limitations [12]. Hence, it is important to pay special attention to the health of this group during a pandemic crisis such as COVID-19.

Despite the debates, vaccination has been accepted as one of the world’s most preventive measures against COVID-19 [13]. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, 13156047747 vaccine doses were administered worldwide until January 25, 2023 [14]. Older adults have been prioritized for receiving the COVID-19 vaccine in many countries, and the vaccination acceptance rate has increased among them [15]. However, two important issues should be considered when vaccinating older adults with frailty. First, many elders are homebound and cannot depart to the health centers for vaccination. Furthermore, there are not enough in-home vaccination services for them in many parts of the world, and many are not even identified [16, 17]. Second, there is no consensus on the vaccine’s effectiveness among this group of older adults [18]. Hussein et al. believed that a weaker immune system in frail older adults causes a poor response to COVID-19 vaccination [19], and Norway reported 23 deaths in frail older adults after vaccination [20]. However, WHO recognized that the vaccine did not result in an unexpected increase in fatalities or any unusual adverse events in most frail older adults [21].

Both frailty and COVID-19 can vastly influence older adults’ biological, psychological, and social aspects [22-24]. Although many studies have considered diagnoses and treatment issues in this group of older adults (e.g. higher mortality rates in COVID-19), the available psychosocial data are mostly outspread, different, or contradictory. Therefore, a comprehensive review is required to collect, integrate, and compare these results to classify our current knowledge. This study aims to review and classify published studies on the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 in frail older adults and identify the knowledge gap with a holistic approach.

Materials and Methods

In the current study, an integrative review method has been applied to explore, summarize, and integrate literature to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the psychosocial aspects of frail older adult’s life during the COVID-19 pandemic. This method allows researchers to collect, classify, evaluate, and analyze quantitative and qualitative papers, detect the knowledge gaps in the literature, link different subject areas, and present new questions or concepts [25]. The study passes five stages.

1) Problem identification, 2) Literature search, 3) Data evaluation, 4) Data analysis, 5) Interpretation and presentation of results (discussion and conclusion) [26].

Literature search and data collection

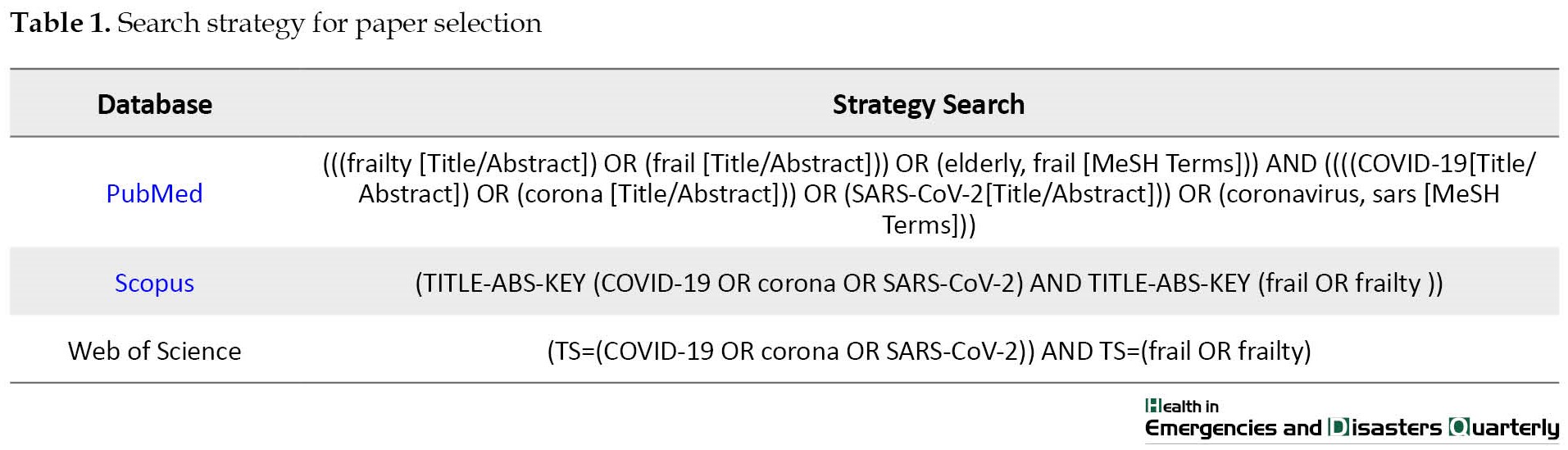

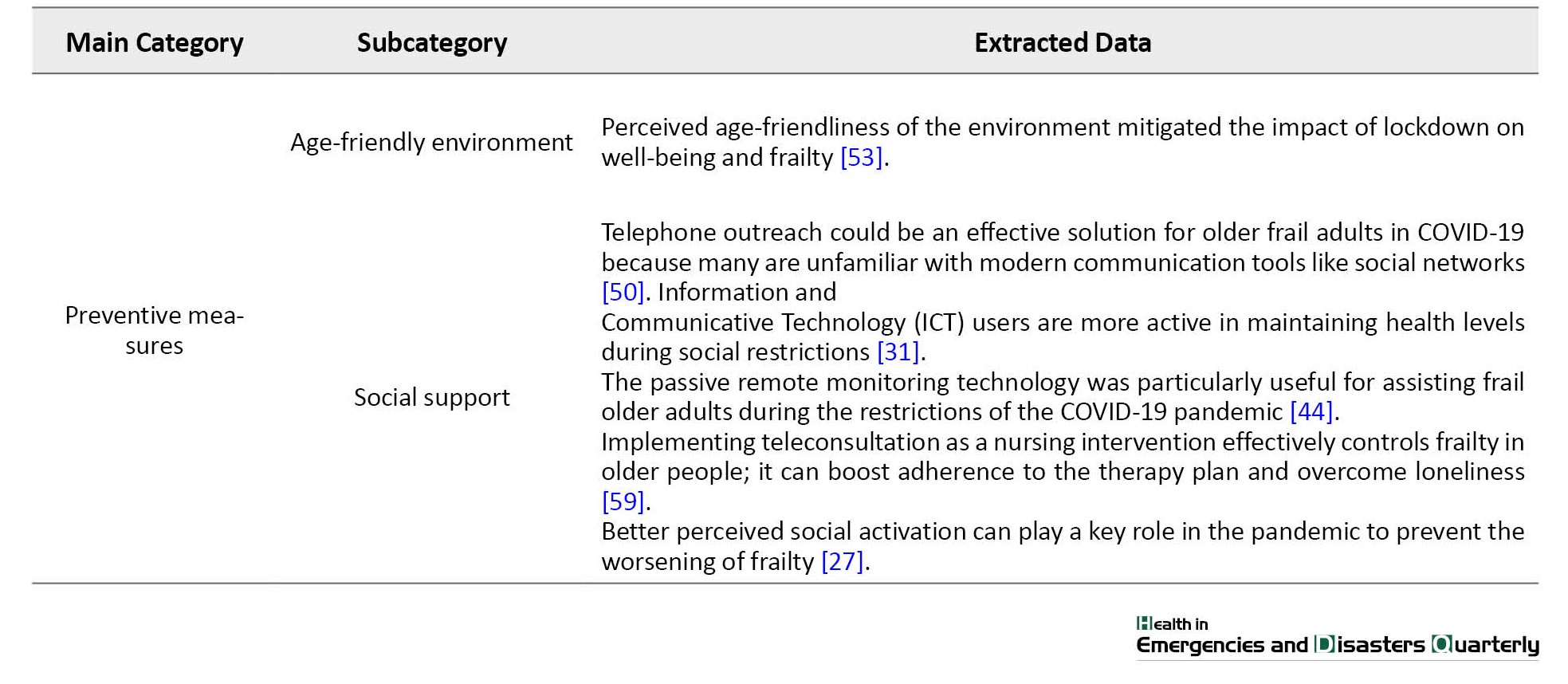

Data collection was conducted between May and August 2022. The inclusion criteria comprised all qualitative and quantitative published papers in the PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases with the search strategy shown in Table 1.

Data evaluation

Following the study objectives, we used the subsequent criteria to evaluate papers and extract the irrelevant papers: A) Studies without having a specific sample group of frail older adults (60 years and over) or without presenting a particular result for them, B) studies on institutionalized individuals and inpatients, C) studies on medical issues such as diagnosis, assessments, treatments, outcomes, prognosis, and mortality rates, D) Case reports, editorials, commentaries, and other papers without specifying a certain method, and E) Papers without available full text, such as poster presentations.

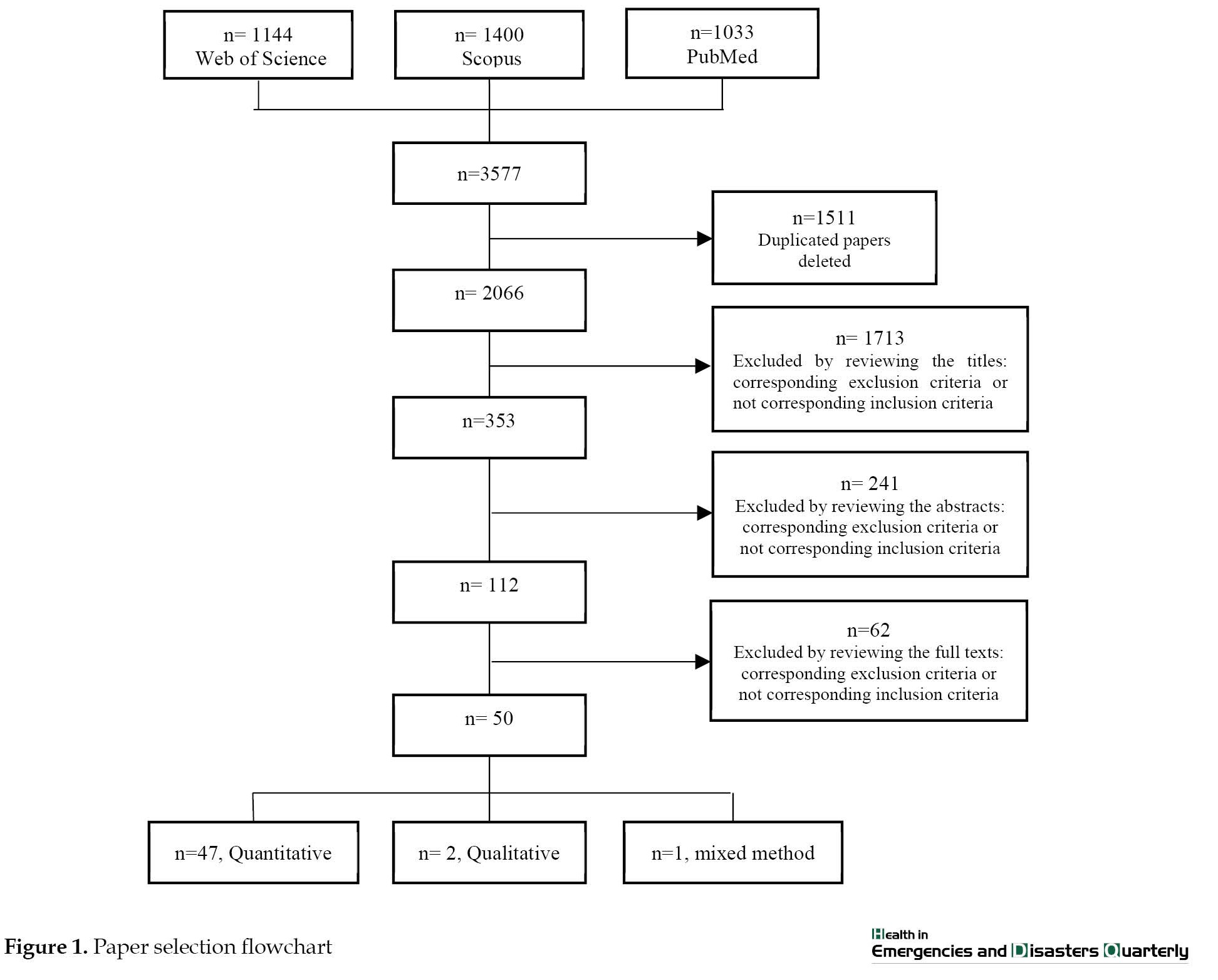

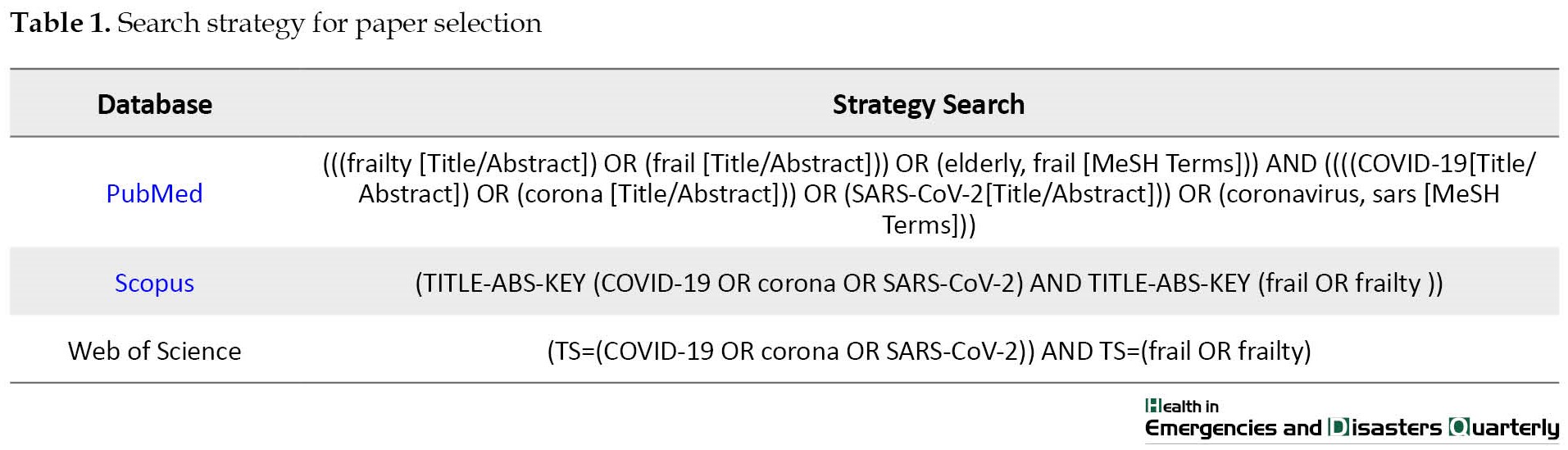

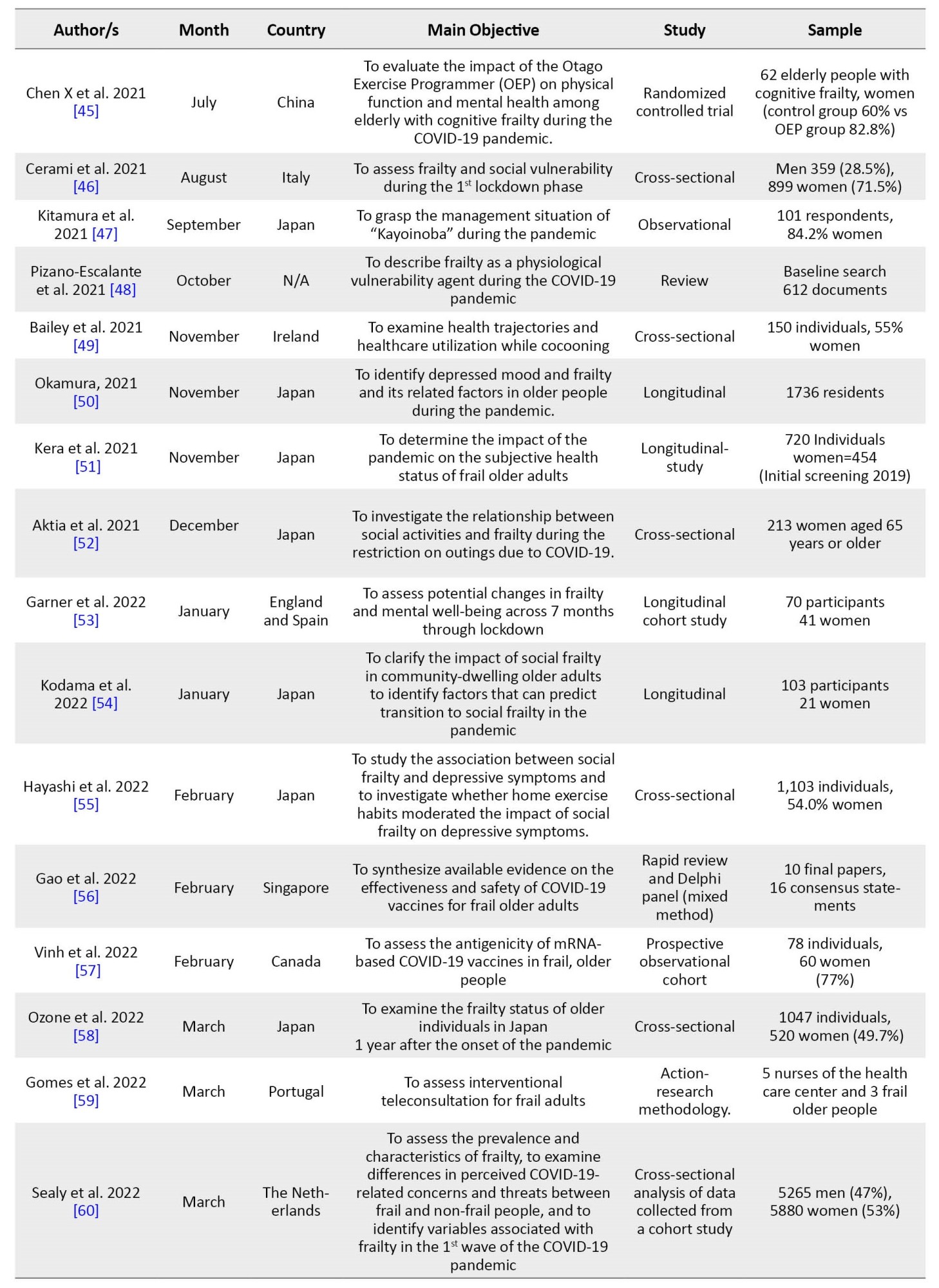

As shown in Figure 1, we initially found 3577 articles, which were reduced to 2066 after removing the duplicates. When the irrelevant titles were removed, this number dropped to 353. We examined the abstracts and omitted those papers that did not meet inclusion criteria or those with corresponding exclusion criteria. Subsequently, 112 papers with full text remained. After review, 50 articles were selected (published between November 2020 and August 2022) for the final analysis (Figure 1).

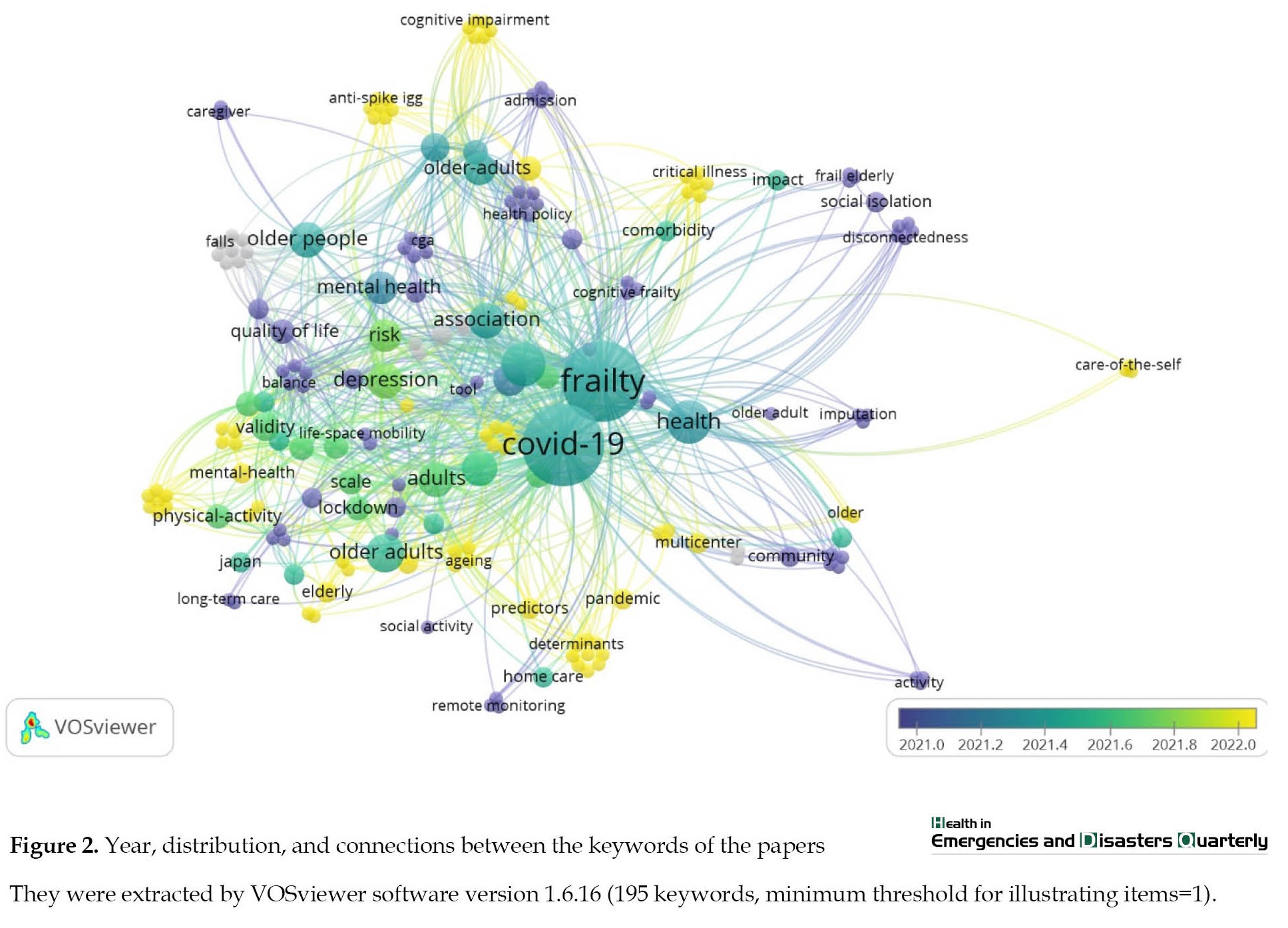

Distribution and connections between the keywords of the final papers were illustrated by a VOSviewer software, version 1.6.16.

3. Results

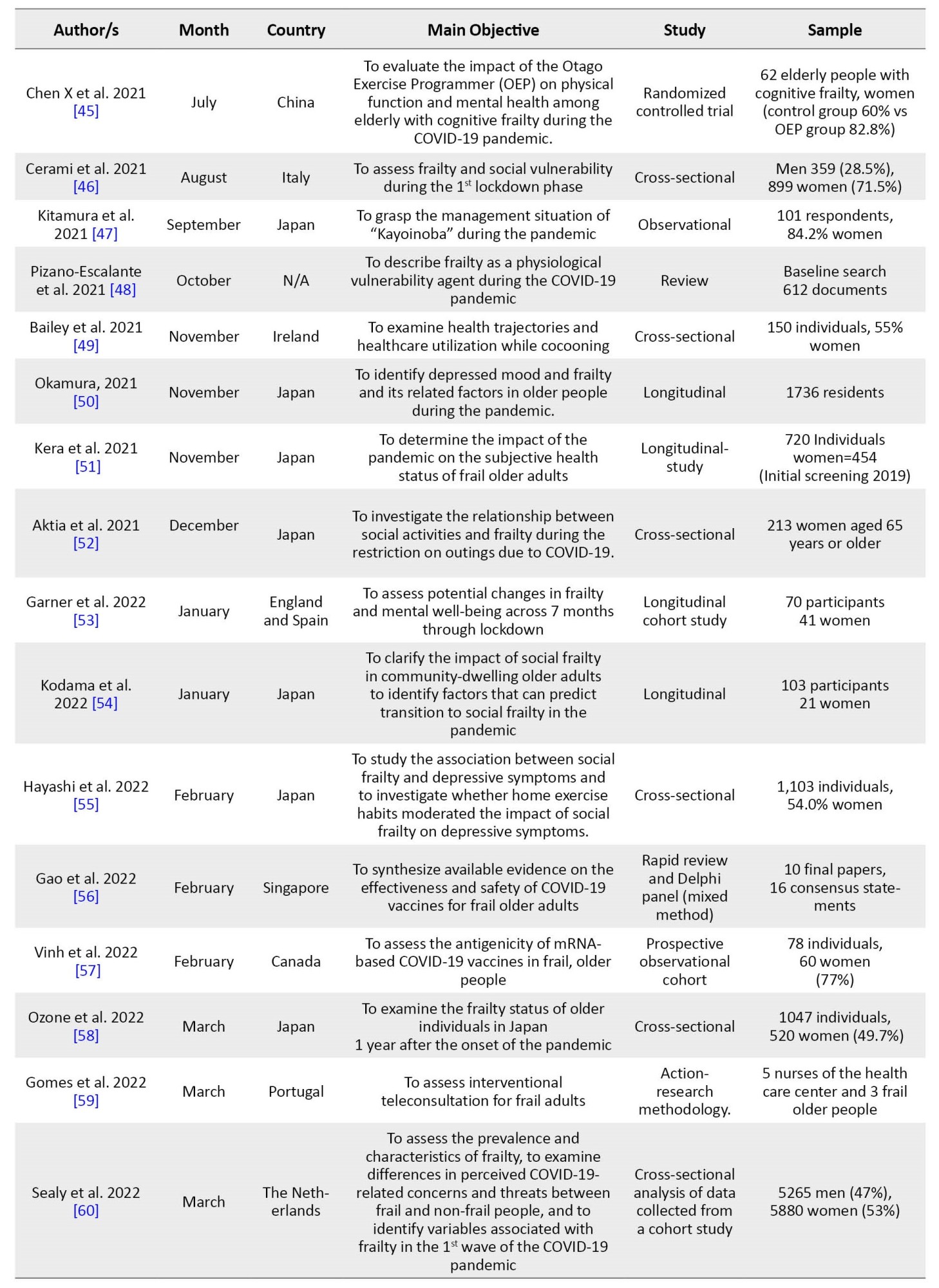

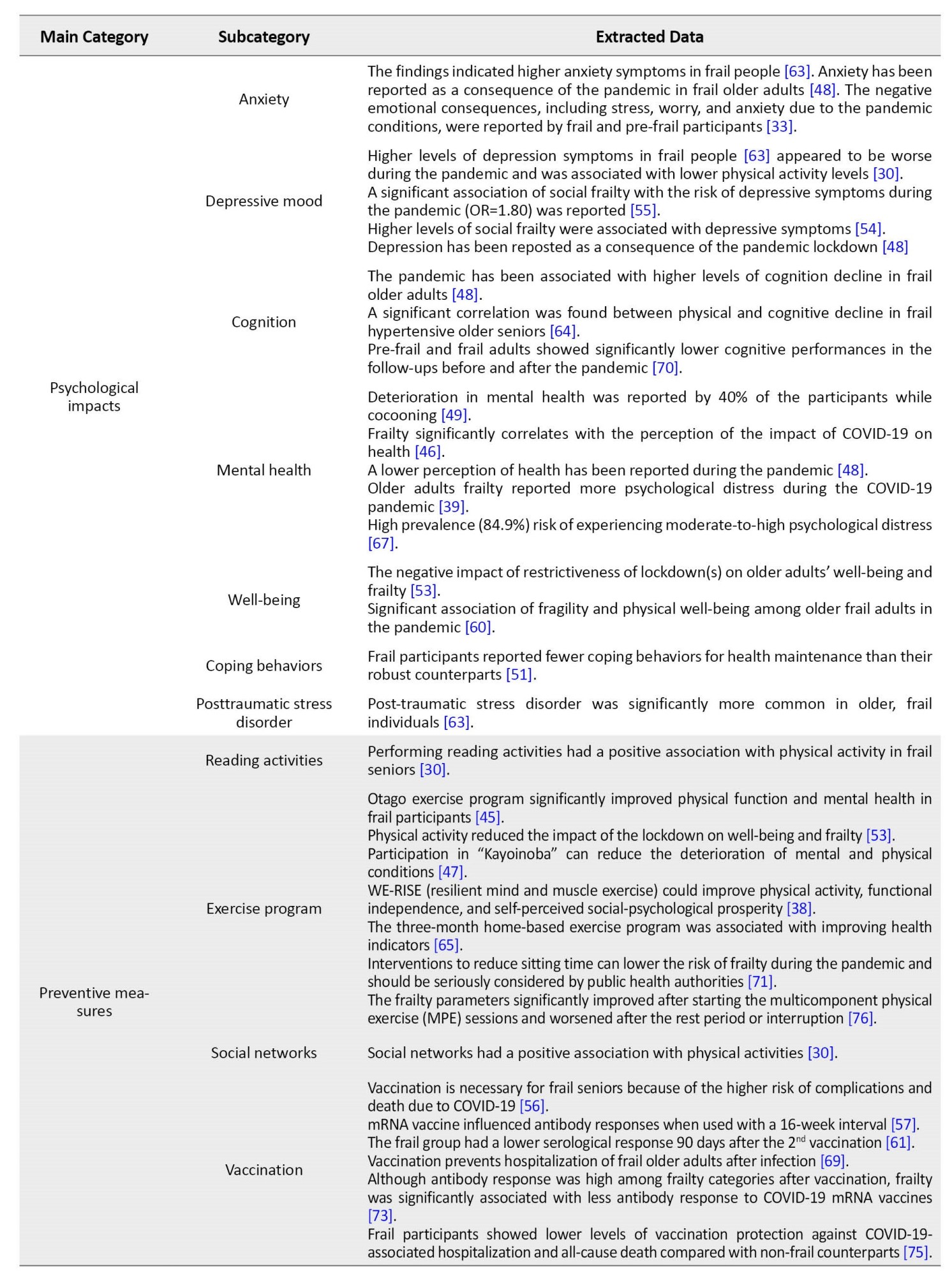

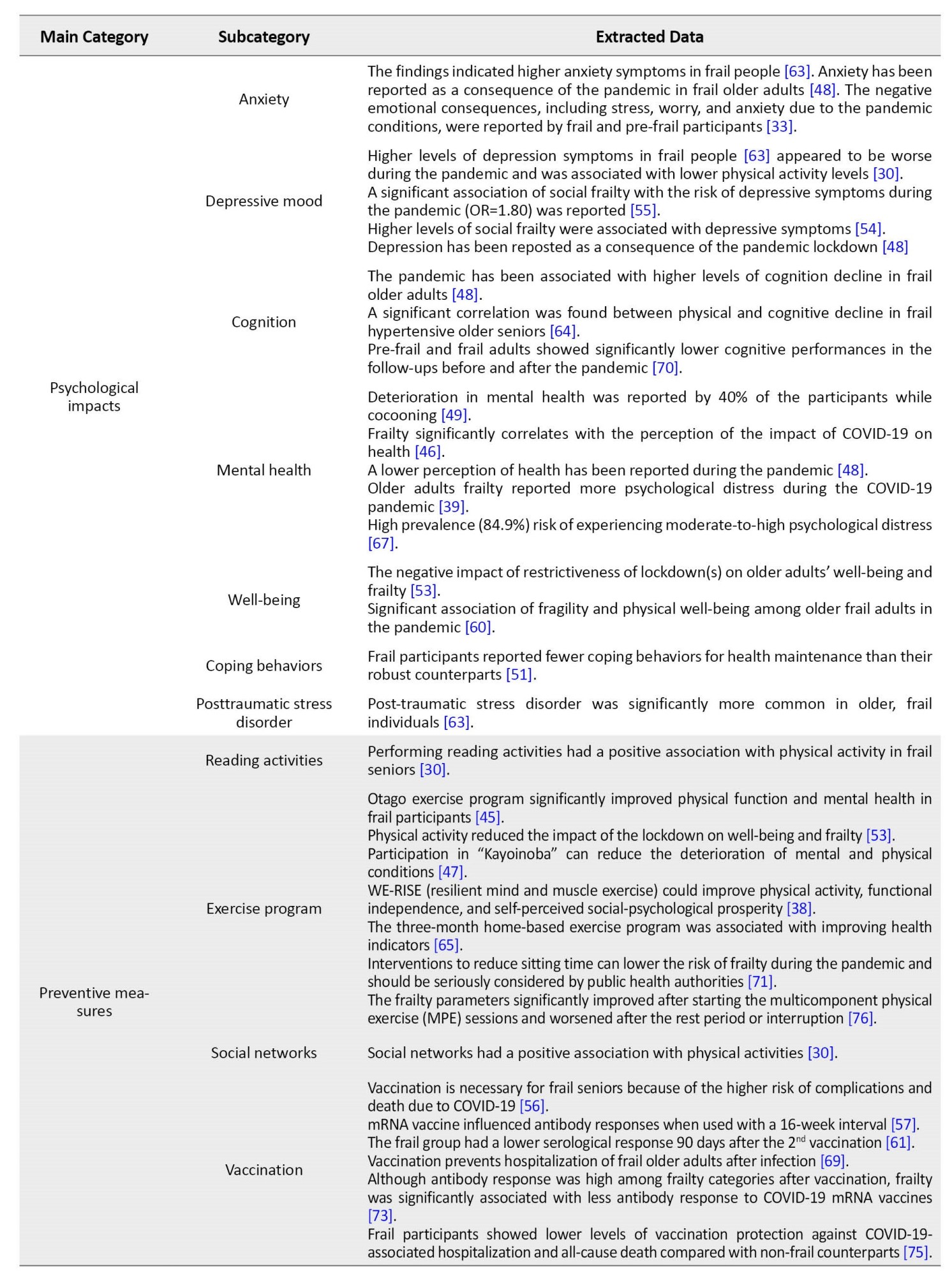

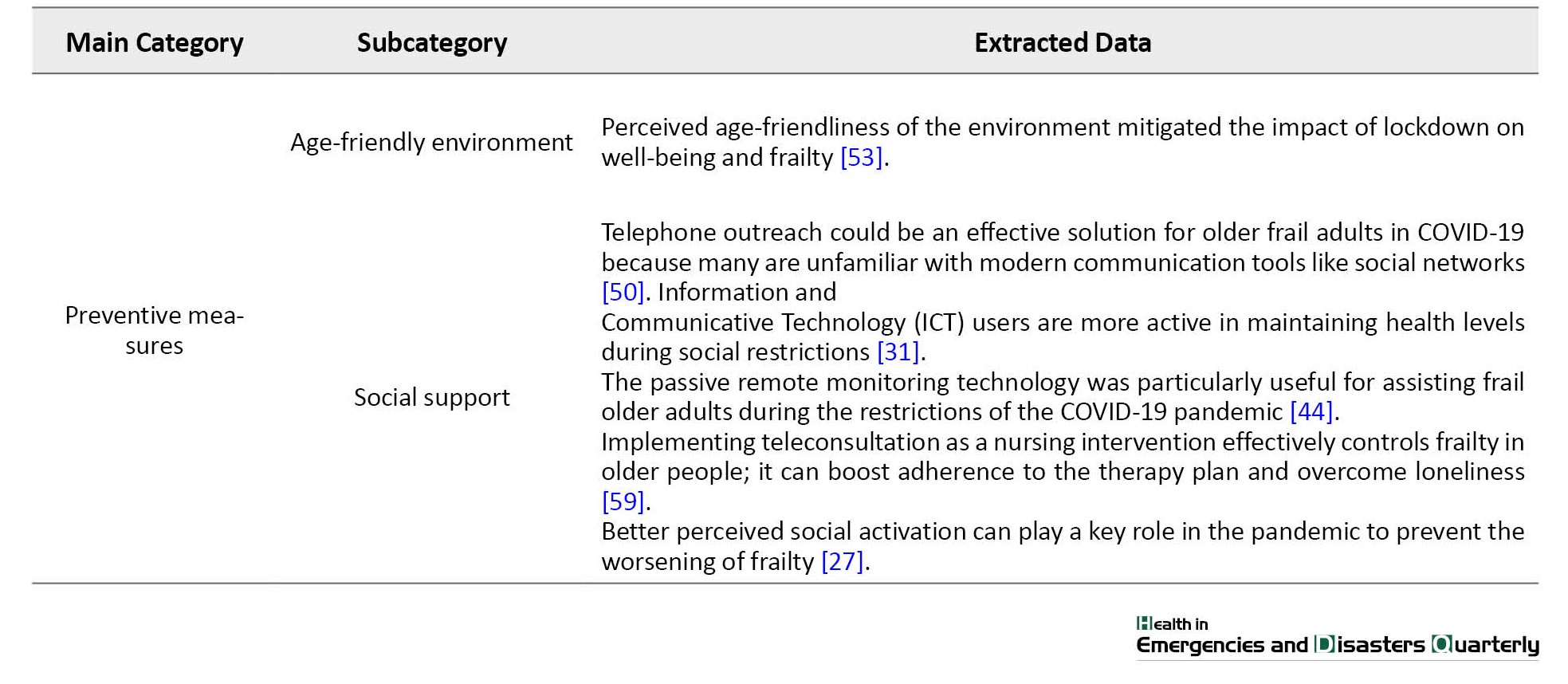

In this study, we categorized the main findings from 50 studies to make them comparable and understandable. Figure 2 displays the distribution and connections between the keywords of the selected papers for final analysis. As shown in Table 2, most studies were qualitative and were conducted in developed countries.

The highest number of studies belonged to Japan (n=13, 26%), Italy (n=5, 10%), Canada, Spain, the UK, the US, and Spain (n=4 each, 8%), and China (n=3, 6%). The main findings of the reviewed papers have been clustered into three categories: Social consequences, psychological impacts, and preventive measures (Table 3).

Social consequences

Much evidence in the current review indicates that the raised prevalence of frailty and the incidence of transition to a frailty state during the COVID-19 pandemic can be due to the implementation of constraints during the crisis [41, 42, 50, 54, 60, 62, 72, 74]. It has been reported that frail seniors’ social activities and interaction with friends and family declined during the pandemic [52]. On the other hand, a lack of social activities was associated with a higher risk of frailty [40, 58]. Older people living alone demonstrated more decline in their physical activities and frailty [30, 36]. Higher levels of frailty and disability have also been reported after COVID-19 hospital discharge [66], and frail survivors require more care [29, 32]. Moreover, the results of some studies indicated that access to medical and social services declined during the pandemic [34, 49, 51, 68], worsening frailty status [35, 37, 43]. These conditions influenced frail seniors’ well-being and quality of life [53, 60].

Psychological impacts

The analysis of the extracted papers indicated that the general mental health of frail older adults deteriorated during the COVID-19 pandemic [39, 46, 48, 49, 67]. Depressive mode and anxiety are two major psychological effects of the pandemic on frail seniors [33, 48, 54, 55, 62, 63]. Depressive mood was associated with lower physical activity and a correlation between cognition and physical decline in frail older adults with hypertension during the pandemic [30, 64]. On the other hand, cognitive deterioration was also reported during the pandemic [48, 70]. Frail older adults reported fewer coping behaviors for health maintenance compared with their robust counterparts, and the restrictiveness of lockdown negatively affected their well-being [51, 53, 60].

Preventive measures

In response to the COVID-19 negative psychosocial impacts on older seniors, the researchers recommended some preventive measures, including simple activities such as reading. One of the dominant non-medical intervention programs to prevent worsening frailty during the pandemic is programmed exercises [38, 45, 47, 53, 65, 76]. Social support is also reported as an important preventive measure as well. Telecommunication facilities were reported as effective tools to identify and meet the needs of frail seniors during the pandemic [31, 44, 50, 59], although some clients were more comfortable with the telephone than using the new technologies [50]. Performing reading activities and boosting social networks were associated with higher physical activity levels [30]. Perceived age-friendliness of the environment mitigated the impact of lockdown on well-being and frailty [53]. There is no consensus on the efficacy of vaccination in frail seniors. Still, as COVID-19 can instigate worse outcomes in frail people, such as more disability and longer care needs, vaccination has been recommended for these vulnerable people [56, 57, 69].

Discussion

The results of the current integrative review indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has complex, serious adverse effects on the psychosocial aspects of the lives of frail seniors. The lockdown, restrictions, and limited access to health services caused a decline in social activities, social relations (resulting in weaker social capital), physical activities, and psychological health, resulting in an increase in the prevalence and incidence of frailty in the pandemic era. These conditions lowered their mental health, quality of life, and perceived well-being. In return, frailty aggravation in the pandemic can also negatively impact psychological health and physical activities. This vicious cycle is shown in Figure 3. Initially, COVID-19 restrictions were implemented to protect people, but such social and physical limitations could negatively affect older adults’ physical activity and mental health [77, 78]. These conditions negatively affect frail older adults and need re-organization of healthcare systems for more sufficient interventions. Additionally, long-term psychological consequences should be considered for this vulnerable group [79]. Anxiety and depression are two psychological consequences of the pandemic restrictions in older adults [80]. Perceived loneliness may also be associated with significant psychological distress due to the lockdown condition [81]. In other words, these effects were more severe among older adults living alone and interacting less with their neighbors [82].

Although social distancing and stay-at-home orders are crucial for frail older adults during pandemics, maintaining social connections with others can reduce social isolation and exclusion [83]. The health benefits of socialization and interaction with others have been highlighted for older adults. As social distancing can reduce these interactions and cognitive stimulation, the solution lies in using technologies such as social media and telephone or video calls for older frail adults, along with appropriate guidance [84].

As frailty manifests itself by physiological declines in different systems, interventions and broad-based approaches are needed to empower frail people and their caregivers during the pandemic [84]. The impacts of limited access to social and health services during the lockdown may accelerate frailty in older adults [79, 80]. Therefore, special attention should be paid to preventive measures. Some of the suggested preventative measures are simple, feasible, and do not require special equipment. For instance, exercises such as strength, balance, and walking are useful for frail older adults during the pandemic to prevent the worsening of frailty [77]. In this regard, telehealth can assist more senior people in following their exercise delivery during the pandemic, and it is potentially more effective in addressing the needs of older adults in remote areas [80]. Interventions through education and telephone follow-up can also reduce the burden of care of caregivers of older adults [85]. Nursing students were reported to have sufficient confidence in using telemedicine for frail people during the pandemic, and they confirmed its validity and importance [86].

Although public vaccination is recognized as an important preventive measure to control contagious diseases, there is still some public mistrust about the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination [15, 18]. Frail adults have been reported to have a weaker immune system, which is a predisposing factor for a higher risk of adverse outcomes and mortality due to COVID-19. This decline can also lead to a poor immune response to vaccination [19]. On the other hand, the results of a study by Seiffert et al. do not confirm the above assumption. They reported that increased anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody levels after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination (with BNT162b2) in long-term facilities did not correlate with frailty and age [87]. It can be assumed that there is a knowledge gap in basic research and clinical practice [88]. Filling these gaps is critical for maintaining confidence in vaccinating frail older adults against COVID-19. In this regard, surveillance and evaluation of COVID-19 vaccination are important. Accordingly, continuous consultation with geriatricians in regulatory and advisory decision-making is necessary [89].

Conclusion

As pandemics such as the COVID-19 outbreak impose great psychosocial strains on frail older adults, more supportive and preventive measures should be taken for them. The results of this review can assist policymakers in considering appropriate social support for frail seniors during pandemics. Prescribing physical and reading activities and boosting social networks can prevent worsening frailty during pandemic-related restrictions. Since most studies are quantitative and have been conducted in developed countries, further qualitative inquiries are suggested to explore the challenges of frail older people during the pandemics in developing countries.

As a limitation of the current review, it should be noted that some studies may have included subgroups of frail older participants in their sample groups without mentioning the word “frail” in their Titles or Abstracts. Even if they presented results and reports on the psychosocial problems of frail seniors, they have not been included in our literature review.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This review study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code.: IR.USWR.REC.1400.097).

Funding

This project was funded by the Deputy of Research and Technology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Choosing the search strategy: Mohammad Saatchi and Arya Hamedanchi; Selection of the papers: Arya Hamedanchi and Nasibeh Zanjari; Resolution of disagreements: Yadollah Abolfathi Momtaz; Rechecking of the papers: Tahereh Ramezani; Final analysis: All authors with the supervision of Ahmad Delbari and Hamid Reza Khankeh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deputy of Research and Technology of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences for their cooperation in the project.

References

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought numerous negative consequences for older adults. The disease has caused additional complications, morbidity, and mortality, particularly in those older adults with underlying diseases [1]. Besides the medical impacts of pathogens, COVID-19 has devastating psychological and social impacts on the general health of older adults [2]. During the pandemic, older adults exhibit higher levels of anxiety, depression, interpersonal conflicts, and social isolation but lower levels of well-being [3, 4, 5, 6]. Evidence suggests that more than 75% of deaths caused by COVID-19 occurred in the age group of 65 years old and over [7]. In addition, higher mortality rates have been reported in frail people [8].Therefore, it has been recommended to take preventive interventions and more targeted approaches to prioritize older adults with comorbidities [9].

Frailty is one of the predisposing factors in older adults, which can increase the prevalence of diseases and incidents among them. As per Xue’s (2011) definition, frailty is “a clinically recognizable state of increased vulnerability resulting from aging-associated decline in reserve and functions across multiple physiologic systems such that the ability to cope with everyday or acute stressors is comprised” [10]. The prevalence of infectious diseases is also remarkably high among frail people [11]. Their access to health services might be difficult due to physical or mental limitations [12]. Hence, it is important to pay special attention to the health of this group during a pandemic crisis such as COVID-19.

Despite the debates, vaccination has been accepted as one of the world’s most preventive measures against COVID-19 [13]. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, 13156047747 vaccine doses were administered worldwide until January 25, 2023 [14]. Older adults have been prioritized for receiving the COVID-19 vaccine in many countries, and the vaccination acceptance rate has increased among them [15]. However, two important issues should be considered when vaccinating older adults with frailty. First, many elders are homebound and cannot depart to the health centers for vaccination. Furthermore, there are not enough in-home vaccination services for them in many parts of the world, and many are not even identified [16, 17]. Second, there is no consensus on the vaccine’s effectiveness among this group of older adults [18]. Hussein et al. believed that a weaker immune system in frail older adults causes a poor response to COVID-19 vaccination [19], and Norway reported 23 deaths in frail older adults after vaccination [20]. However, WHO recognized that the vaccine did not result in an unexpected increase in fatalities or any unusual adverse events in most frail older adults [21].

Both frailty and COVID-19 can vastly influence older adults’ biological, psychological, and social aspects [22-24]. Although many studies have considered diagnoses and treatment issues in this group of older adults (e.g. higher mortality rates in COVID-19), the available psychosocial data are mostly outspread, different, or contradictory. Therefore, a comprehensive review is required to collect, integrate, and compare these results to classify our current knowledge. This study aims to review and classify published studies on the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 in frail older adults and identify the knowledge gap with a holistic approach.

Materials and Methods

In the current study, an integrative review method has been applied to explore, summarize, and integrate literature to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the psychosocial aspects of frail older adult’s life during the COVID-19 pandemic. This method allows researchers to collect, classify, evaluate, and analyze quantitative and qualitative papers, detect the knowledge gaps in the literature, link different subject areas, and present new questions or concepts [25]. The study passes five stages.

1) Problem identification, 2) Literature search, 3) Data evaluation, 4) Data analysis, 5) Interpretation and presentation of results (discussion and conclusion) [26].

Literature search and data collection

Data collection was conducted between May and August 2022. The inclusion criteria comprised all qualitative and quantitative published papers in the PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases with the search strategy shown in Table 1.

Data evaluation

Following the study objectives, we used the subsequent criteria to evaluate papers and extract the irrelevant papers: A) Studies without having a specific sample group of frail older adults (60 years and over) or without presenting a particular result for them, B) studies on institutionalized individuals and inpatients, C) studies on medical issues such as diagnosis, assessments, treatments, outcomes, prognosis, and mortality rates, D) Case reports, editorials, commentaries, and other papers without specifying a certain method, and E) Papers without available full text, such as poster presentations.

As shown in Figure 1, we initially found 3577 articles, which were reduced to 2066 after removing the duplicates. When the irrelevant titles were removed, this number dropped to 353. We examined the abstracts and omitted those papers that did not meet inclusion criteria or those with corresponding exclusion criteria. Subsequently, 112 papers with full text remained. After review, 50 articles were selected (published between November 2020 and August 2022) for the final analysis (Figure 1).

Distribution and connections between the keywords of the final papers were illustrated by a VOSviewer software, version 1.6.16.

3. Results

In this study, we categorized the main findings from 50 studies to make them comparable and understandable. Figure 2 displays the distribution and connections between the keywords of the selected papers for final analysis. As shown in Table 2, most studies were qualitative and were conducted in developed countries.

The highest number of studies belonged to Japan (n=13, 26%), Italy (n=5, 10%), Canada, Spain, the UK, the US, and Spain (n=4 each, 8%), and China (n=3, 6%). The main findings of the reviewed papers have been clustered into three categories: Social consequences, psychological impacts, and preventive measures (Table 3).

Social consequences

Much evidence in the current review indicates that the raised prevalence of frailty and the incidence of transition to a frailty state during the COVID-19 pandemic can be due to the implementation of constraints during the crisis [41, 42, 50, 54, 60, 62, 72, 74]. It has been reported that frail seniors’ social activities and interaction with friends and family declined during the pandemic [52]. On the other hand, a lack of social activities was associated with a higher risk of frailty [40, 58]. Older people living alone demonstrated more decline in their physical activities and frailty [30, 36]. Higher levels of frailty and disability have also been reported after COVID-19 hospital discharge [66], and frail survivors require more care [29, 32]. Moreover, the results of some studies indicated that access to medical and social services declined during the pandemic [34, 49, 51, 68], worsening frailty status [35, 37, 43]. These conditions influenced frail seniors’ well-being and quality of life [53, 60].

Psychological impacts

The analysis of the extracted papers indicated that the general mental health of frail older adults deteriorated during the COVID-19 pandemic [39, 46, 48, 49, 67]. Depressive mode and anxiety are two major psychological effects of the pandemic on frail seniors [33, 48, 54, 55, 62, 63]. Depressive mood was associated with lower physical activity and a correlation between cognition and physical decline in frail older adults with hypertension during the pandemic [30, 64]. On the other hand, cognitive deterioration was also reported during the pandemic [48, 70]. Frail older adults reported fewer coping behaviors for health maintenance compared with their robust counterparts, and the restrictiveness of lockdown negatively affected their well-being [51, 53, 60].

Preventive measures

In response to the COVID-19 negative psychosocial impacts on older seniors, the researchers recommended some preventive measures, including simple activities such as reading. One of the dominant non-medical intervention programs to prevent worsening frailty during the pandemic is programmed exercises [38, 45, 47, 53, 65, 76]. Social support is also reported as an important preventive measure as well. Telecommunication facilities were reported as effective tools to identify and meet the needs of frail seniors during the pandemic [31, 44, 50, 59], although some clients were more comfortable with the telephone than using the new technologies [50]. Performing reading activities and boosting social networks were associated with higher physical activity levels [30]. Perceived age-friendliness of the environment mitigated the impact of lockdown on well-being and frailty [53]. There is no consensus on the efficacy of vaccination in frail seniors. Still, as COVID-19 can instigate worse outcomes in frail people, such as more disability and longer care needs, vaccination has been recommended for these vulnerable people [56, 57, 69].

Discussion

The results of the current integrative review indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has complex, serious adverse effects on the psychosocial aspects of the lives of frail seniors. The lockdown, restrictions, and limited access to health services caused a decline in social activities, social relations (resulting in weaker social capital), physical activities, and psychological health, resulting in an increase in the prevalence and incidence of frailty in the pandemic era. These conditions lowered their mental health, quality of life, and perceived well-being. In return, frailty aggravation in the pandemic can also negatively impact psychological health and physical activities. This vicious cycle is shown in Figure 3. Initially, COVID-19 restrictions were implemented to protect people, but such social and physical limitations could negatively affect older adults’ physical activity and mental health [77, 78]. These conditions negatively affect frail older adults and need re-organization of healthcare systems for more sufficient interventions. Additionally, long-term psychological consequences should be considered for this vulnerable group [79]. Anxiety and depression are two psychological consequences of the pandemic restrictions in older adults [80]. Perceived loneliness may also be associated with significant psychological distress due to the lockdown condition [81]. In other words, these effects were more severe among older adults living alone and interacting less with their neighbors [82].

Although social distancing and stay-at-home orders are crucial for frail older adults during pandemics, maintaining social connections with others can reduce social isolation and exclusion [83]. The health benefits of socialization and interaction with others have been highlighted for older adults. As social distancing can reduce these interactions and cognitive stimulation, the solution lies in using technologies such as social media and telephone or video calls for older frail adults, along with appropriate guidance [84].

As frailty manifests itself by physiological declines in different systems, interventions and broad-based approaches are needed to empower frail people and their caregivers during the pandemic [84]. The impacts of limited access to social and health services during the lockdown may accelerate frailty in older adults [79, 80]. Therefore, special attention should be paid to preventive measures. Some of the suggested preventative measures are simple, feasible, and do not require special equipment. For instance, exercises such as strength, balance, and walking are useful for frail older adults during the pandemic to prevent the worsening of frailty [77]. In this regard, telehealth can assist more senior people in following their exercise delivery during the pandemic, and it is potentially more effective in addressing the needs of older adults in remote areas [80]. Interventions through education and telephone follow-up can also reduce the burden of care of caregivers of older adults [85]. Nursing students were reported to have sufficient confidence in using telemedicine for frail people during the pandemic, and they confirmed its validity and importance [86].

Although public vaccination is recognized as an important preventive measure to control contagious diseases, there is still some public mistrust about the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination [15, 18]. Frail adults have been reported to have a weaker immune system, which is a predisposing factor for a higher risk of adverse outcomes and mortality due to COVID-19. This decline can also lead to a poor immune response to vaccination [19]. On the other hand, the results of a study by Seiffert et al. do not confirm the above assumption. They reported that increased anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody levels after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination (with BNT162b2) in long-term facilities did not correlate with frailty and age [87]. It can be assumed that there is a knowledge gap in basic research and clinical practice [88]. Filling these gaps is critical for maintaining confidence in vaccinating frail older adults against COVID-19. In this regard, surveillance and evaluation of COVID-19 vaccination are important. Accordingly, continuous consultation with geriatricians in regulatory and advisory decision-making is necessary [89].

Conclusion

As pandemics such as the COVID-19 outbreak impose great psychosocial strains on frail older adults, more supportive and preventive measures should be taken for them. The results of this review can assist policymakers in considering appropriate social support for frail seniors during pandemics. Prescribing physical and reading activities and boosting social networks can prevent worsening frailty during pandemic-related restrictions. Since most studies are quantitative and have been conducted in developed countries, further qualitative inquiries are suggested to explore the challenges of frail older people during the pandemics in developing countries.

As a limitation of the current review, it should be noted that some studies may have included subgroups of frail older participants in their sample groups without mentioning the word “frail” in their Titles or Abstracts. Even if they presented results and reports on the psychosocial problems of frail seniors, they have not been included in our literature review.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This review study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code.: IR.USWR.REC.1400.097).

Funding

This project was funded by the Deputy of Research and Technology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Choosing the search strategy: Mohammad Saatchi and Arya Hamedanchi; Selection of the papers: Arya Hamedanchi and Nasibeh Zanjari; Resolution of disagreements: Yadollah Abolfathi Momtaz; Rechecking of the papers: Tahereh Ramezani; Final analysis: All authors with the supervision of Ahmad Delbari and Hamid Reza Khankeh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deputy of Research and Technology of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences for their cooperation in the project.

References

- Moradi M, Navab E, Sharifi F, Namadi B, Rahimidoost M. [The Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the elderly: A systematic review (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2021; 16(1):2-29. [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.3106.1]

- Verma R, Kilgour HM, Haase KR. The psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on older adults with cancer: A rapid review. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(2):589-601. [DOI:10.3390/curroncol29020053] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Olyani S, Peyman N. [Assessment of the subjective wellbeing of the elderly during the COVID-19 disease pandemic in Mashhad (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2021; 16(1):62-73. [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.3109.1]

- Rashedi V, Roshanravan M, Borhaninejad V, Mohamadzadeh M. [Coronavirus anxiety and obsession, depression and activities of daily living among older adults in Mane and Semelghan (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2022; 17(2):186-201. [DOI:10.32598/sija.2022.1857.2]

- Gholamzad S, Saeidi N, Danesh S, Ranjbar H, Zarei M. [Analyzing the elderly’s quarantine-related experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2021; 16(1):30-45. [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.2083.3]

- Hosseini Moghaddam F, Amiri Delui M, Sadegh Moghadam L, Kameli F, Moradi M, Khajavian N, et al. [Prevalence of depression and its related factors during the COVID-19 quarantine among the elderly in Iran (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2021; 16(1):140-51. [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.2850.1]

- Khankeh H, Farrokhi M, Ghadicolaei HT, Mazhin SA, Roudini J, Mohsenzadeh Y, et al. Epidemiology and factors associated with COVID-19 outbreak-related deaths in patients admitted to medical centers of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2021; 10:426. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_192_21] [PMID]

- Andrew M, Godin J, LeBlanc J, Boivin G, Valiquette L, McElhaney JE, et al. Older age and frailty are associated with higher mortality but lower intensive care unit admission among adults admitted to Canadian hospitals with COVID-19: A report from the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) serious outcomes surveillance network. 2021; 16:731-8. [DOI:10.2147/CIA.S295522] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Akhavizadegan H, Aghaziarati M, Roshanfekr Balalemi MG, Arman Broujeni Z, Taghizadeh F, Akbarzadeh Arab I, et al. [Relationship between comorbidity, chronic diseases, ICU hospitalization, and death rate in the elderly with Coronavirus infection (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2021; 16(1):86-101. [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.3161.1]

- Xue Q-L. The frailty syndrome: Definition and natural history. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2011; 27(1):1-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Saeidimehr S, Delbari A, Zanjari N, Fadaye Vatan R. [Factors related to frailty among older adults in Khuzestan, Iran (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2021;16(2):202-17. [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.2.1600.1]

- Ghasemi S, Keshavarz Mohammadi N, Mohammadi Shahboulaghi F, Ramezankhani A, Mehrabi Y. [Physical health status and frailty index in community dwelling older adults in Tehran (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2019; 13(5):652-65. [DOI:10.32598/SIJA.13.Special-Issue.652]

- Khankeh H, Tabrizchi N. An overview of the policies of selected countries in controlling COVID-19 outbreak (Persian)]. Journal of Culture and Health Promotion. 2021; 4(3):338-46. [Link]

- WHO. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Geneva: WHO; 2023. [Link]

- Khankeh HR, Farrokhi M, Khanjani MS, Momtaz YA, Forouzan AS, Norouzi M, et al. The barriers, challenges, and strategies of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine acceptance: A concurrent mixed-method study in Tehran City, Iran. Vaccines. 2021; 9(11):1248. [DOI:10.3390/vaccines9111248] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Stall N, Nakamachi Y, Chang M. Mobile in-home COVID-19 vaccination of Ontario homebound older adults by neighbourhood risk. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. 2021; 1:19. [DOI:10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.19.1.0]

- Whiteman A, Wang A, McCain K, Gunnels B, Toblin R, Lee JT, et al. Demographic and social factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination initiation among adults aged ≥65 years - United States, December 14, 2020-April 10, 2021. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021; 70(19):725–30. [DOI:10.15585/mmwr.mm7019e4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rolland Y, Cesari M, Morley JE, Merchant R, Vellas B. Editorial: COVID-19 vaccination in frail people. Lots of hope and some questions. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2021; 25(2):146-7. [DOI:10.1007/s12603-021-1591-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hussien H, Nastasa A, Apetrii M, Nistor I, Petrovic M, Covic A. Different aspects of frailty and COVID-19: Points to consider in the current pandemic and future ones. BMC Geriatrics. 2021; 21(1):389. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-021-02316-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Torjesen I. COVID-19: Norway investigates 23 deaths in frail elderly patients after vaccination. British Medical Journal Publishing Group. 2021; 372:n149. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.n149] [PMID]

- WHO. GACVS COVID-19 Vaccine safety subcommittee meeting to review reports of deaths of very frail elderly individuals vaccinated with Pfizer BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, BNT162b2. Geneva: WHO; 2021. [Link]

- Teo N, Yeo PS, Gao Q, Nyunt MSZ, Foo JJ, Wee SL, et al. A bio-psycho-social approach for frailty amongst Singaporean Chinese community-dwelling older adults - evidence from the Singapore Longitudinal Aging Study. BMC Geriatrics. 2019; 19(1):350. [DOI:0.1186/s12877-019-1367-9.] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kojima G, Iliffe S, Jivraj S, Walters K. Association between frailty and quality of life among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2016; 70(7):716-21. [DOI:10.1136/jech-2015-206978] [PMID]

- Nandasena HMRKG, Pathirathna ML, Atapattu AMMP, Prasanga PTS. Quality of life of COVID 19 patients after discharge: Systematic review. PloS One. 2022; 17(2):e0263941. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0263941] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005; 52(5):546-53. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x] [PMID]

- Russell CL. An overview of the integrative research review Progress in Transplantation. 2005; 15(1):8-13. [DOI:10.1177/152692480501500102] [PMID]

- Pandolfini V, Poli S, Torrigiani C. Frailty and its social predictors among older people: Some empirical evidences and a lesson from COVID-19 for revising public health and social policies. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education. 2020; 12(3):151-76. [Link]

- Saraiva MD, Apolinario D, Avelino-Silva TJ, de Assis Moura Tavares C, Gattás-Vernaglia IF, Marques Fernandes C, et al. The impact of frailty on the relationship between life-space mobility and quality of life in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2021; 25(4):440-7. [DOI:10.1007/s12603-020-1532-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vilches-Moraga A, Price A, Braude P, Pearce L, Short R, Verduri A, et al. Increased care at discharge from COVID-19: The association between pre-admission frailty and increased care needs after hospital discharge; A multicentre European observational cohort study. BMC Medicine. 2020; 18(1):408. [DOI:10.1186/s12916-020-01856-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Pérez LM, Castellano-Tejedor C, Cesari M, Soto-Bagaria L, Ars J, Zambom-Ferraresi F, et al. Depressive symptoms, fatigue and social relationships influenced physical activity in frail older community-dwellers during the Spanish lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):808. [DOI:0.3390/ijerph18020808.] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Satake S, Kinoshita K, Arai H. More active participation in voluntary exercise of older users of information and communicative technology even during the COVID-19 pandemic, independent of frailty status. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2021; 25(4):516-9. [DOI:10.1007/s12603-021-1598-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Geriatric Medicine Research Collaborative; Covid Collaborative; Welch C. Age and frailty are independently associated with increased COVID-19 mortality and increased care needs in survivors: Results of an international multi-centre study. Age and Ageing. 2021; 50(3):617-30. [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afab026] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Chen AT, Ge S, Cho S, Teng AK, Chu F, Demiris G, et al. Reactions to COVID-19, information and technology use, and social connectedness among older adults with pre-frailty and frailty. Geriatric Nursing. 2021; 42(1):188-95. [DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.08.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Liu L, Goodarzi Z, Jones A, Posno R, Straus SE, Watt JA. Factors associated with virtual care access in older adults: A cross-sectional study. Age and Ageing. 2021; 50(4):1412-5. [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afab021] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hirose T, Sawaya Y, Shiba T, Ishizaka M, Onoda K, Kubo A, et al. Characteristics of patients discontinuing outpatient services under long-term care insurance and its effect on frailty during COVID-19. PeerJ. 2021; 9:e11160. [DOI:10.7717/peerj.11160] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Yamada M, Kimura Y, Ishiyama D, Otobe Y, Suzuki M, Koyama S, et al. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and new incidence of frailty among initially non-frail older adults in Japan: A follow-up online survey. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2021; 25(6):751-6. [DOI:10.1007/s12603-021-1634-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Schuster NA, de Breij S, Schaap LA, van Schoor NM, Peters MJL, de Jongh RT, et al. Older adults report cancellation or avoidance of medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. European Geriatric Medicine. 2021; 12(5):1075-83. [DOI:10.1007/s41999-021-00514-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Murukesu RR, Singh DKA, Shahar S, Subramaniam P. Physical activity patterns, psychosocial well-being and coping strategies among older persons with cognitive frailty of the "WE-RISE" trial throughout the COVID-19 movement control order. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2021; 16:415-29. [DOI:10.2147/CIA.S290851] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wang Y, Fu P, Li J, Jing Z, Wang Q, Zhao D, et al. Changes in psychological distress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults: The contribution of frailty transitions and multimorbidity. Age and Ageing. 2021; 50(4):1011-8. [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afab061] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Morina N, Kip A, Hoppen TH, Priebe S, Meyer T. Potential impact of physical distancing on physical and mental health: A rapid narrative umbrella review of meta-analyses on the link between social connection and health. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(3):e042335. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042335] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mete B, Tanir F, Kanat C. The effect of fear of COVID-19 and social isolation on the fragility in the elderly. Turkish Journal of Geriatrics. 2021; 24(1):23-31. [Link]

- Shinohara T, Saida K, Tanaka S, Murayama A, Higuchi D. Did the number of older adults with frailty increase during the COVID-19 pandemic? A prospective cohort study in Japan. European Geriatric Medicine. 2021; 12(5):1085-9. [DOI:10.1007/s41999-021-00523-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kawamura K, Kamiya M, Suzumura S, Maki K, Ueda I, Itoh N, et al. Impact of the Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak on activity and exercise levels among older patients. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2021; 25(7):921-5. [DOI:10.1007/s12603-021-1648-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Weeks LE, Nesto S, Hiebert B, Warner G, Luciano W, Ledoux K, et al. Health service experiences and preferences of frail home care clients and their family and friend caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Research Notes. 2021; 14(1):271. [DOI:10.1186/s13104-021-05686-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Chen X, Zhao L, Liu Y, Zhou Z, Zhang H, Wei D, et al. Otago exercise programme for physical function and mental health among older adults with cognitive frailty during COVID-19: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2021; 21:10.1111/jocn.15964. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.15964] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cerami C, Canevelli M, Santi GC, Galandra C, Dodich A, Cappa SF, et al. Identifying frail populations for disease risk prediction and intervention planning in the COVID-19 era: A focus on social isolation and vulnerability. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021; 12:626682. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626682] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kitamura M, Goto T, Fujiwara S, Shirayama Y. Did "Kayoinoba" Prevent the decline of mental and physical functions and frailty for the home-based elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9502. [DOI:.3390/ijerph18189502] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Pizano-Escalante MG, Anaya-Esparza LM, Nuño K, Rodríguez-Romero JJ, Gonzalez-Torres S, López-de la Mora DA, et al. Direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 in frail elderly: Interventions and recommendations. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(10):999. [DOI:10.3390/jpm11100999] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bailey L, Ward M, DiCosimo A, Baunta S, Cunningham C, Romero-Ortuno R, et al. Physical and mental health of older people while cocooning during the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians. 2021; 114(9):648-53. [DOI:10.1093/qjmed/hcab015] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Okamura T, Sugiyama M, Inagaki H, Miyamae F, Ura C, Sakuma N, et al. Depressed mood and frailty among older people in Tokyo during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychogeriatrics: The Official Journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society. 2021; 21(6):892-901. [DOI:10.1111/psyg.12764] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kera T, Kawai H, Ejiri M, Takahashi J, Nishida K, Harai A, et al. Change in subjective health status among frail older Japanese people owing to the Coronavirus disease pandemic and characteristics of their responses. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2021; 21(11):1053-9. [DOI:10.1111/ggi.14276] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Akita M, Otaki N, Yokoro M, Yano M, Tanino N, Fukuo K. Relationship between social activity and frailty in Japanese older women during restriction on outings due to COVID-19. Canadian Geriatrics Journal: CGJ. 2021; 24(4):320-4. [DOI:10.5770/cgj.24.507] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Garner IW, Varey S, Navarro-Pardo E, Marr C, Holland CA. An observational cohort study of longitudinal impacts on frailty and well-being of COVID-19 lockdowns in older adults in England and Spain. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2022; 30(5):e2905-16. [DOI:10.1111/hsc.13735] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kodama A, Kume Y, Lee S, Makizako H, Shimada H, Takahashi T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic exacerbation of depressive symptoms for social frailty from the ORANGE Registry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):986. [DOI:0.3390/ijerph19020986] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hayashi T, Noguchi T, Kubo Y, Tomiyama N, Ochi A, Hayashi H. Social frailty and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults in Japan: Role of home exercise habits. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2022; 98:104555. [DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2021.104555] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gao J, Lun P, Ding YY, George PP. COVID-19 vaccination for frail older adults in Singapore - Rapid evidence summary and delphi consensus statements. Journal of Frailty and Aging. 2022; 11(2):236-41. [DOI:10.14283/jfa.2022.12] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vinh DC, Gouin JP, Cruz-Santiago D, Canac-Marquis M, Bernier S, Bobeuf F, et al. Real-world serological responses to extended-interval and heterologous COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in frail, older people (UNCoVER): An interim report from a prospective observational cohort study. The Lancet. Healthy Longevity. 2022; 3(3):e166-75. [DOI:10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00012-5] [PMID]

- Ozone S, Goto R, Kawada S, Yokoya S. Frailty and social participation in older citizens in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of General and Family Medicine. 2022; 23(4):255-60. [DOI:10.1002/jgf2.539] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gomes ID, Sobreira LS, da Cruz HDT, Almeida I, de Souza MCMR, et al. Teleconsultation script for intervention on frail older person to promote the Care-of-the-Self: A gerontotechnology tool in a pandemic context. In: García-Alonso J, Fonseca C, editors. Gerontechnology IV. IWoG 2021. Lecture Notes in Bioengineering. Cham: Springer; 2022.[DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-97524-1_13]

- Sealy MJ, van der Lucht F, van Munster BC, Krijnen WP, Hobbelen H, Barf HA, et al. Frailty among older people during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3669. [DOI:0.3390/ijerph19063669] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Okyar Baş A, Hafizoğlu M, Akbiyik F, Güner Oytun M, Şahiner Z, Ceylan S, et al. Antibody response with SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine (CoronaVac) in Turkish geriatric population. Age and Ageing. 2022; 51(5):afac088. [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afac088] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bricio-Barrios JA, Ríos-Silva M, Huerta M, Cárdenas-María RY, García-Ibáñez AE, Díaz-Mendoza MG, et al. Impact on the nutritional and functional status of older Mexican adults in the absence of recreational activities due to COVID-19: A longitudinal study from 2018 to 2021. Journal of Applied Gerontology: the Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society. 2022; 41(9):2096-2104. [DOI:10.1177/07334648221099278] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Braude P, McCarthy K, Strawbridge R, Short R, Verduri A, Vilches-Moraga A, et al. Frailty is associated with poor mental health 1 year after hospitalisation with COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022; 310:377-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.035] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mone P, Pansini A, Frullone S, de Donato A, Buonincontri V, De Blasiis P, et al. Physical decline and cognitive impairment in frail hypertensive elders during COVID-19. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2022; 99:89-92. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejim.2022.03.012] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Watanabe R, Kojima M, Yasuoka M, Kimura C, Kamiji K, Otani T, et al. Home-Based frailty prevention program for older women participants of Kayoi-No-Ba during the COVID-19 pandemic: A feasibility study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6609. [DOI:0.3390/ijerph19116609] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Taniguchi LU, Avelino-Silva TJ, Dias MB, Jacob-Filho W, Aliberti MJR; COVID-19 and Frailty (CO-FRAIL) Study Group and EPIdemiology of Critical COVID-19 (EPICCoV) Study Group, for COVID Hospital das Clinicas, University of Sao Paulo Medical School (HCFMUSP) Study Group. Patient-centered outcomes following COVID-19: Frailty and disability transitions in critical care survivors. Critical Care Medicine. 2022; 50(6):955-63. [DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000005488] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Castellano-Tejedor C, Pérez LM, Soto-Bagaria L, Risco E, Mazo MV, Gómez A, et al. Correlates to psychological distress in frail older community-dwellers undergoing lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatrics. 2022; 22(1):516. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-03072-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Subramaniam A, Pilcher D, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson J, Mitchell H, Xu D, et al. Timely goals of care documentation in patients with frailty in the COVID-19 era: A retrospective multi-site study. Internal Medicine Journal. 2022; 52(6):935-43. [DOI:10.1111/imj.15671] [PMID]

- Seligman B, Ikuta K, Orshansky G, Goetz MB. Frailty, vaccination, and hospitalization following COVID-19 positivity in older veterans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2022; 70(7):1941-3. [DOI:10.1111/jgs.17919] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sardella A, Chiara E, Alibrandi A, Bellone F, Catalano A, Lenzo V, et al. Changes in cognitive and functional status and in quality of life of older outpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontology. 2022; 68(11):1285-90.[DOI:10.1159/000525041] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Li N, Huang F, Li H, Lin S, Yuan Y, Zhu P. Examining the independent and interactive association of physical activity and sedentary behaviour with frailty in Chinese community-dwelling older adults. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):1414. [DOI:0.1186/s12889-022-3842-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- McArthur C, Turcotte LA, Sinn CJ, Berg K, Morris JN, Hirdes JP. Social engagement and distress among home care recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2022; 23(7):1101-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2022.04.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Semelka CT, DeWitt ME, Callahan KE, Herrington DM, Alexander-Miller MA, Yukich JO, et al. Frailty and COVID-19 mRNA vaccine antibody response in the COVID-19 community research partnership. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2022; 77(7):1366-70. [DOI:10.1093/gerona/glac095] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Pilotto A, Custodero C, Zora S, Poli S, Senesi B, Prete C, et al. Frailty trajectories in community-dwelling older adults during COVID-19 pandemic: The PRESTIGE study. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2022; 52(12):e13838. [DOI:10.1111/eci.13838] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tang F, Hammel IS, Andrew MK, Ruiz JG. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine effectiveness against hospitalisation and death in veterans according to frailty status during the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant surge in the USA: A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Healthy Longevity. 2022; 3(9):e589-98. [DOI:10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00166-0] [PMID]

- Markotegi M, Irazusta J, Sanz B, Rodriguez-Larrad A. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the physical and psychoaffective health of older adults in a physical exercise program. Experimental Gerontology. 2021; 155:111580. [DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2021.111580] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Aubertin-Leheudre M, Rolland Y. The importance of physical activity to care for frail older adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020; 21(7):973-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.04.022] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Norouzi Seyed Hosseini R. [Understanding the lived experiences of athlete elderly in COVID-19 pandemic in Tehran (A phenomenological approach) (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2021; 16(1):46-61. [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.3000.1]

- Briguglio M, Giorgino R, Dell'Osso B, Cesari M, Porta M, Lattanzio F, et al. Consequences for the elderly after COVID-19 isolation: FEaR (Frail Elderly amid Restrictions). Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11:565052. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565052] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Pelicioni PHS, Schulz-Moore JS, Hale L, Canning CG, Lord SR. Lockdown during COVID-19 and the increase of frailty in people with neurological conditions. Frontiers in Neurology. 2020; 11:604299. [DOI:10.3389/fneur.2020.604299] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lozupone M, La Montagna M, Di Gioia I, Sardone R, Resta E, Daniele A, et al. Social frailty in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020; 11:577113. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577113] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Yamada M, Arai H. Implication of frailty and disability prevention measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Medicine (Milton (NSW)). 2021; 4(4):242-6. [DOI:10.1002/agm2.12182] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Okamura T, Ura C, Sugiyama M, Kugimiya Y, Okamura M, Ogawa M, et al. Defending community living for frail older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychogeriatrics: The Official Journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society. 2020; 20(6):944-5. [DOI:10.1111/psyg.12598] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Boreskie KF, Hay JL, Duhamel TA. Preventing frailty progression during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Frailty & Aging. 2020; 9(3):130-1. [DOI:10.14283/jfa.2020.29] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bani Ardalan H, Motalebi SA, Shahrokhi A, Mohammadi F. [Effect of education and telephone follow-up on care burden of caregivers of older patients with stroke (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2022; 17(2):290-303. [DOI:10.32598/sija.2022.2183.3]

- Brownie SM, Chalmers LM, Broman P, Andersen P. Evaluating an undergraduate nursing student telehealth placement for community-dwelling frail older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2022; 32(1-2):147-62. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.16208] [PMID]

- Seiffert P, Konka A, Kasperczyk J, Kawa J, Lejawa M, Maślanka-Seiffert B, et al. Immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in older residents of a long-term care facility: Relation with age, frailty and prior infection status. Biogerontology. 2022; 23(1):53-64. [DOI:10.1007/s10522-021-09944-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Palermo S. COVID-19 pandemic: Maximizing future vaccination treatments considering aging and frailty. Frontiers in Medicine. 2020; 7:558835. [DOI:10.3389/fmed.2020.558835] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Andrew MK, Schmader KE, Rockwood K, Clarke B, McElhaney JE. Considering frailty in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development: How geriatricians can assist. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2021; 16:731-8. [DOI:10.2147/CIA.S295522] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2023/05/9 | Accepted: 2023/09/4 | Published: 2023/09/11

Received: 2023/05/9 | Accepted: 2023/09/4 | Published: 2023/09/11

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |