Volume 9, Issue 3 (Spring 2024)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2024, 9(3): 173-182 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Najafi M, Fathi S. Examining the Relationship Between Burnout and Personality Traits in Accidents and Disasters’ Rescuers. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2024; 9 (3) :173-182

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-535-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-535-en.html

1- Department of Rescue and Relief, Iran-Helal Higher Education Institute, Tehran, Iran. , najafirc@gmail.com

2- Red Crescent Society of Tehran Province, Tehran, Iran.

2- Red Crescent Society of Tehran Province, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 499 kb]

(47 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (157 Views)

Full-Text: (20 Views)

Introduction

Bradley proposed burnout as a psychological phenomenon for the first time; however, the American psychiatrist, Herbert Freudenberger, is regarded as the originator of the concept, who described this syndrome in full detail in his influential article in 1974 entitled, "employee burnout". as a result, it provided the ground for its introduction [1]. Later, Maslach developed the concept of burnout and presented a multi-dimensional model of it [2]. Accordingly, burnout is a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. Emotional exhaustion is characterized by a lack of energy and includes feelings of disinterest, fear of returning to work, helplessness, hopelessness, dissatisfaction, and feeling trapped at work. In this case, the person feels that their emotional resources have been emptied in such a way that they can no longer continue fulfilling their responsibilities toward clients as in the past. Emotional exhaustion is the main dimension related to stress in burnout. Depersonalization is related to the negative attitude toward others and the feeling of separation and alienation from them. The feeling of alienation can show itself by withdrawing from clients and customers, physical separation in interactions, absence from work, late arrival, and excessive use of jokes. Depersonalization shows the interpersonal dimension of burnout [2]. The last component of burnout is reduced personal accomplishment. This is related to the feeling of incompetence and lack of productivity at work. The sense of reduced efficiency can be reinforced by the feeling of inadequacy to help clients and customers. This feeling leads to a person feeling defeated. Reduced personal accomplishment shows a person's tendency to negatively evaluate themselves. The personal accomplishment component shows the self-assessment dimension of burnout [3].

It is usually assumed that rescuers know what to do in any rescue situation. This belief leads to the thinking that the savior is a powerful person with sufficient physical and mental resources, can be easily compatible with what happened, and does not experience any problems in the face of accidents and disasters. Various studies indicate the risk of rescuers suffering from emotional and psychological problems and complications [4, 5]. The amount of mental pressure of a rescuer depends on various variables. Among them, we can mention the rescuers' coping and adaptation strategies and mechanisms, their personality variables, previous experiences, the severity and number of damages and injuries from accidents and disasters, in addition to many other cultural and social factors [6]. Burnout in rescuers of accidents and disasters can affect the health of victims by affecting their performance. On the other hand, paying less attention to personality traits in the selection of rescuers may cause more burnout in them. To the best of our knowledge, no study was conducted in Iran to examine the relationship between burnout and personality traits in rescuers. Hence, this study examines the relationship between burnout and some of their personality traits based on the research conducted on the rescuers of the Red Crescent Society of Tehran Province (T- RCS), Iran. With the results of this study, appropriate criteria can be provided for the selection of rescuers in this regard.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional correlational study conducted in December 2022. In this research, the correlation research design was used to determine whether a relationship exists between the burnout of rescuers and their personality traits. The studied population included all the rescuers of the 16 branches of the T- RCS, who work in 19 rescue centers. Rescuers are people who attend the scene of the accident through Red Crescent rescue bases and provide aid to the victims of accidents. The sample size was 414 people. To determine the minimum required sample size, the Morgan table was used (for more accuracy and to ensure the completion of the required questionnaires, a larger sample size was considered). Due to the clarity of the sampling framework, the samples were randomly selected from the statistical population, and out of 270 distributed questionnaires, after removing the incomplete questionnaires, 254 questionnaires were analyzed. Considering that all the rescuers at the rescue centers are men, the subjects in this study were all men. These rescuers included volunteers and rescue personnel of the T- RCS, Iran.

Since no natural disaster (such as flood, earthquake, etc.) occurred during the month before this research, all the incidents that these rescuers faced during the month before the research were unnatural disasters (such as road accidents or mountain accidents).

Meslach burnout inventory (MBI) was used to evaluate the burnout of the participants in this study. This questionnaire is a gold standard measurement tool to measure burnout and includes three independent measurement subscales. The emotional exhaustion subscale evaluates being tired of work and emotional overactivity. The depersonalization subscale examines the degree of insensitivity. And, the lack of personality and personal accomplishment subscale investigates a person’s sense of adequacy and work success. The questionnaire has 22 items which are divided into three subscales. For each item in terms of frequency, a 7-point scale is considered, according to the respondent’s experience with that item, they choose one (from 0=never to 6=every day). Nine items are related to the subscale of emotional exhaustion, which evaluates prolonged emotions and fatigue caused by a person’s work. Five items are related to the depersonalization subscale, which measures apathy toward the services provided to the recipients of these services. A moderate correlation is observed between these two subscales, although each one measures a different aspect of burnout. For both subscales of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, high scores indicate high levels of burnout. Eight items are related to the subscale of personal accomplishment, which measures the sense of competence and success in working with people. Unlike the other two subscales, low scores in this subscale indicate high levels of burnout. The subscale of personal efficiency is independent from the other two subscales. In other words, the correlation between the subscale of personal efficiency and the other two subscales is weak. The completed questionnaire of each respondent is graded based on the instructions for scoring each subscale. The scores of each subscale should be calculated separately and should not be added together and expressed as a single score. Therefore, three scores are calculated for each respondent. Each score can be expressed as low, medium, and high based on the classification [7].

In MBI, the minimum score for each subscale is zero and the maximum score for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment are 54, 30, and 48, respectively. In this questionnaire, emotional exhaustion scores between 0 and 16 are considered low level, while scores from 17 to 26 are considered medium level, and more than 27 is regarded as high level. We consider the depersonalization score between 0 and 6 as a low level, between 7 and 12 as a medium level, and more than 13 as a high level. In the case of personal accomplishment, the scale is reversed. Then, if the personal accomplishment score is above 37, it is regarded as a low level, if it is between 31 and 36, it is considered medium level and if it is between zero and 30, it is considered high level [8]. A high score of emotional exhaustion a high score of depersonalization or a low score of personal accomplishment show high levels of burnout.

To examine the reliability of this questionnaire, Maslash and Jackson evaluated the internal consistency of the questionnaire with the Cronbach α coefficient, which showed a reliability coefficient of 0.83. They also showed the validity of this questionnaire by examining its convergent validity and discriminant validity [9]. In a study conducted in Iran, the reliability of the subscales of the questionnaire (Persian version) was between 0.80 and 0.94. This study has also shown that the content validity ratio and content validity index in the Persian version is 0.87, which shows that all the questions in the questionnaire have high content validity [10].

In this research, the investigated personality traits are based on a well-known theory called the five-factor model of personality, which is also known as the big five factors. The five factors are neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness [11].

The short form of the neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (NEO) questionnaire was used to measure the mentioned personality traits in the rescuers of the T- RCS. This questionnaire is a type of personality trait self-assessment questionnaire that is based on the five-factor model. This questionnaire contains 60 questions. In this questionnaire, each 12 questions is for one feature, and each feature, the minimum score is zero while the maximum score is 48.

Regarding the reliability of the short-form of NEO, studies show good internal stability for its subscales. For example, McCrae and Costa reported the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.68 for agreeableness and 0.86 for neuroticism. Holden also reported the Cronbach α coefficient of these 5 factors in the range of 0.76 (for openness) to 0.87 (for neuroticism). About the validity of the short-form NEO subscales, McCrae and Costa have stated that the shortened NEO tool corresponds exactly with its full form, in such a way that the subscales of the short form correlate higher than 0.68 with the subscales of the full form [12].

The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire have been conducted in Iran. In the study by Anisi et al. the results of reliability analysis using the Cronbach α method showed that the characteristics of conscientiousness, neuroticism, agreeableness, extroversion, and openness were 0.83, 0.80, 0.60, 0.58, and 0.39, respectively. In addition, the subscales of this questionnaire had a correlation coefficient of 0.47 to 0.68 with the corresponding subscales in the Eysenk personality questionnaire [13].

Results

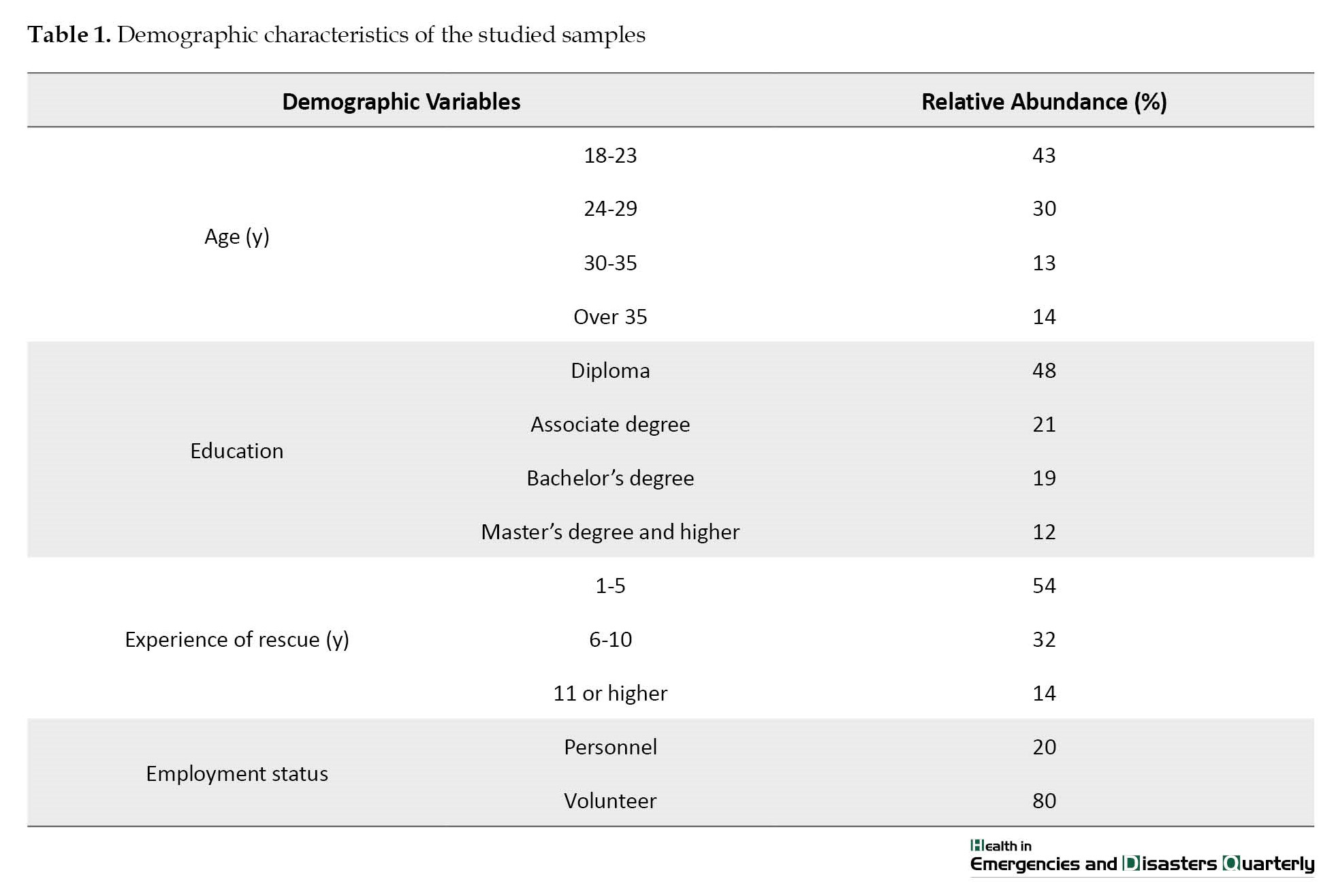

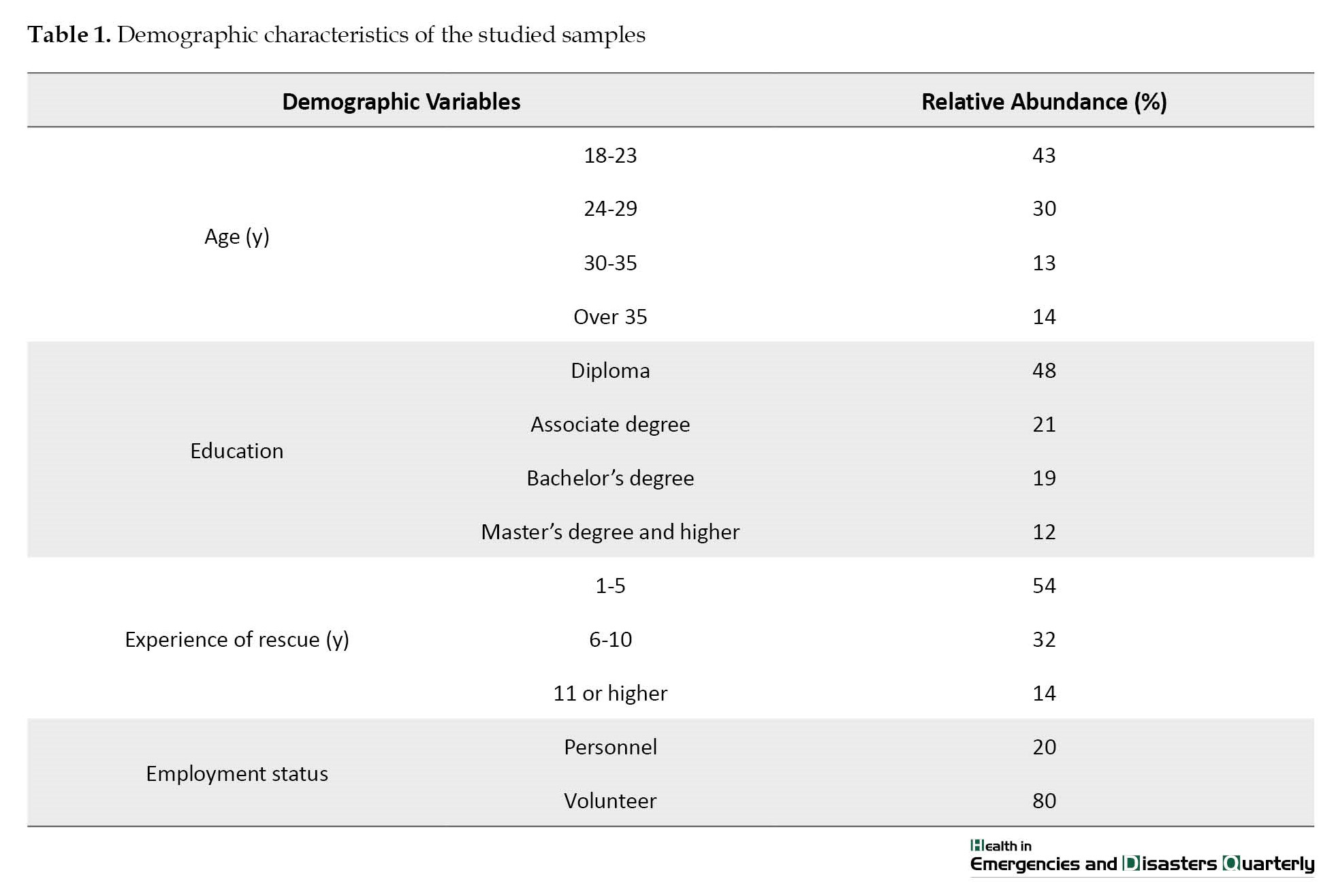

Among the 270 distributed questionnaires, 254 questionnaires were analyzed. Considering that all the rescuers at the rescue centers are men, the subjects in this study were all male. Most respondents were between 18 and 23 years old, and in terms of education, most of them had a diploma. Most respondents were volunteers and often had between 1 and 5 years of rescue experience (Table 1).

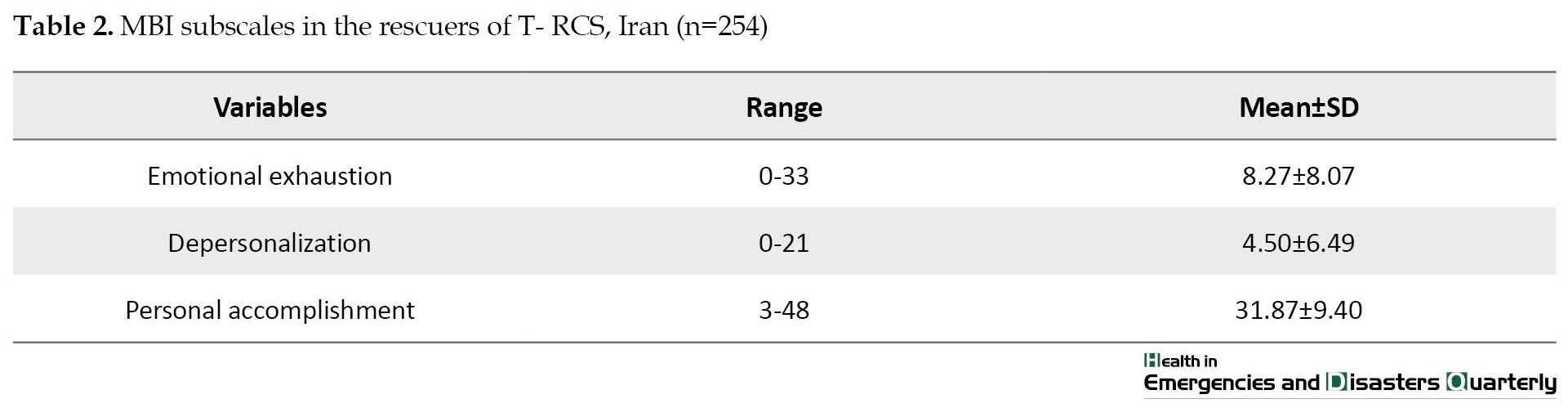

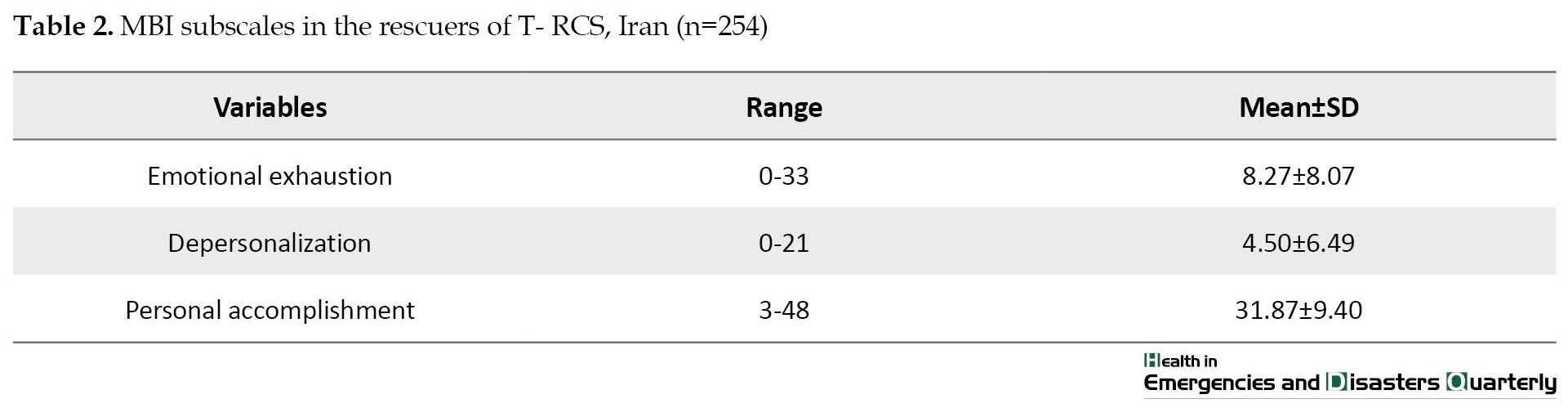

To check the level of burnout in rescuers, the average subscales of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment were measured in the subjects (Table 2).

Additionally, in terms of emotional exhaustion, 70.7% of rescuers (the highest frequency) were in the group with a low level of burnout, and only 2.7% of them (the lowest frequency) were in the group with a high level of burnout. Meanwhile, 11.4% of rescuers experienced a moderate level of burnout and 15.2% of them did not fully answer the questions in this section.

Also, in terms of depersonalization, 68% of rescuers (the highest frequency) were in the group with a low level of burnout. Meanwhile, 7.1% of them were in the group with a high level (lowest frequency) and 14.8% of them were in the group with a medium level of burnout. Nevertheless, 10.1% of the respondents did not fully answer the questions in this section.

In terms of personal accomplishment, 32.7% of rescuers (the highest frequency) were in the group with a high level of burnout, 23.2% of them were in the group with an average level of burnout, and 29.3% of them were in the group with a low level of burnout. Also, 14.8% of them did not fully answer the questions in this section.

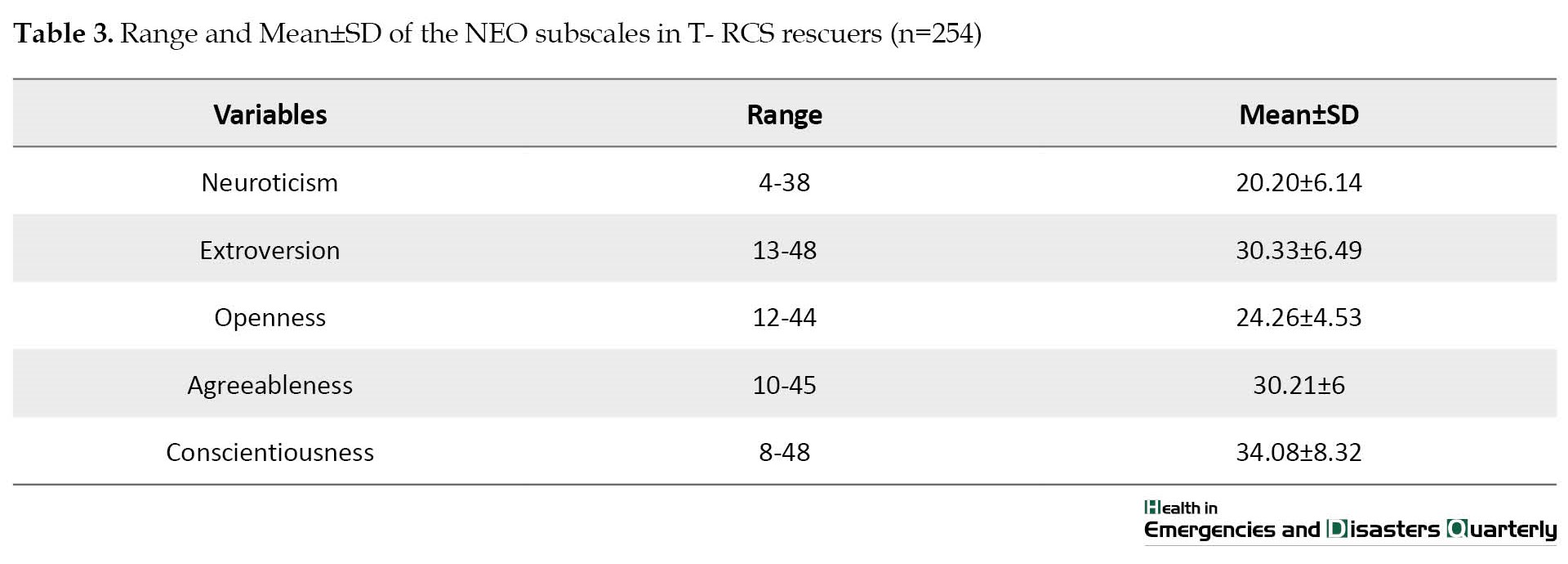

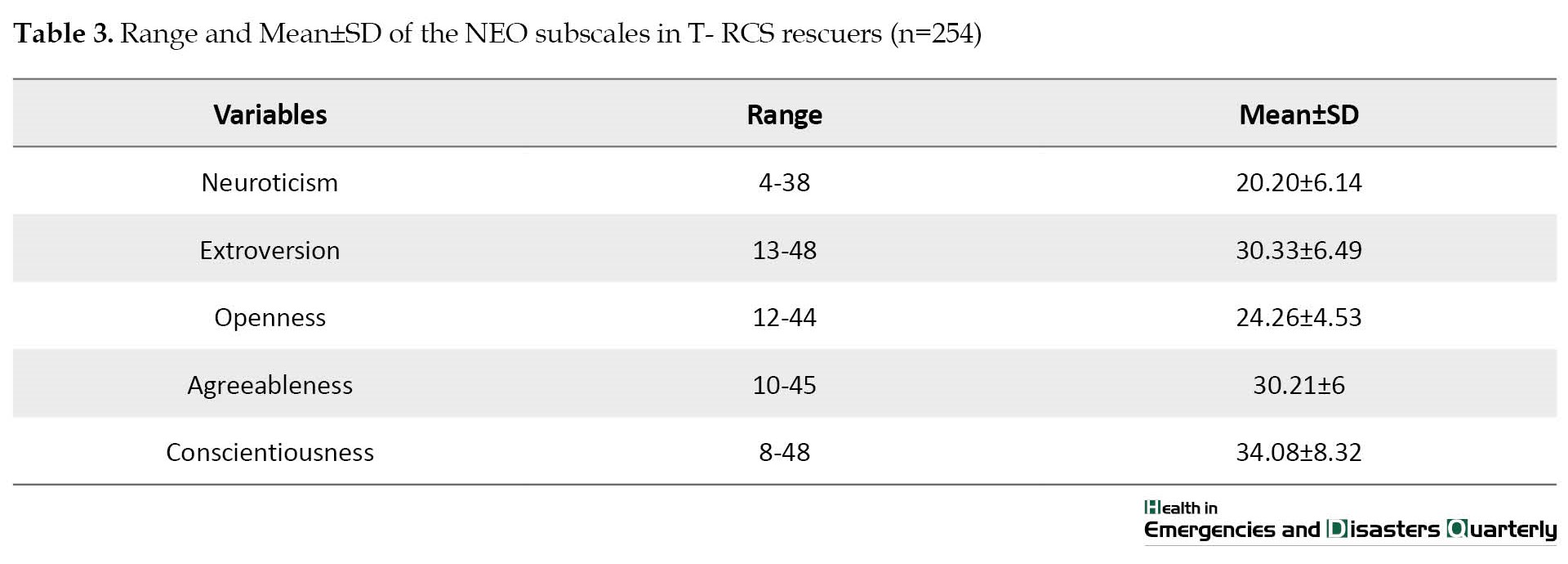

In examining the subscales of the NEO questionnaire, the highest mean score of the subjects was related to the conscientiousness personality trait (34.08±8.32), and the lowest mean score was related to the neuroticism personality trait (20.20±6.14) (Table 3).

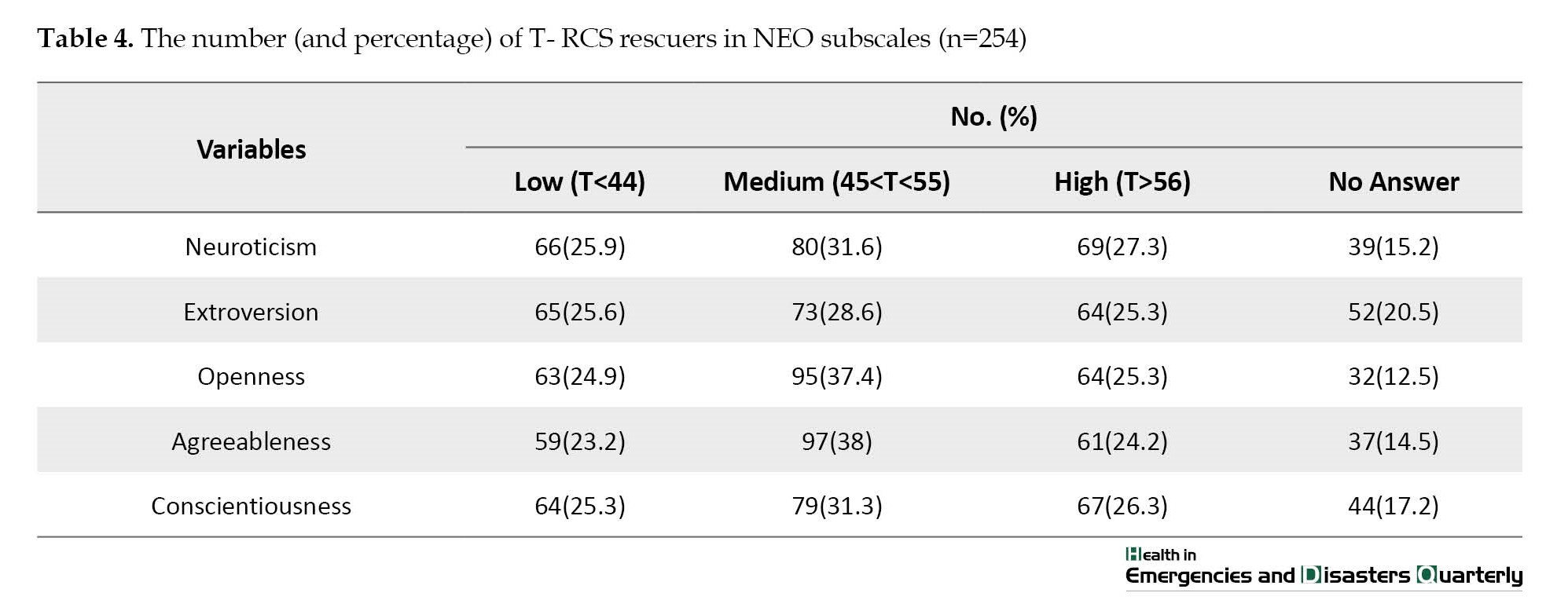

To categorize the scores related to the five big personality factors, first, the raw scores of each factor were converted into Z scores, and then the T score of each was calculated (T=10+Z50). Subsequently, the obtained scores were classified into three groups low score (T≥44), medium score (T≥45≥55), and high score (T≤56). They were analyzed based on the classified data.

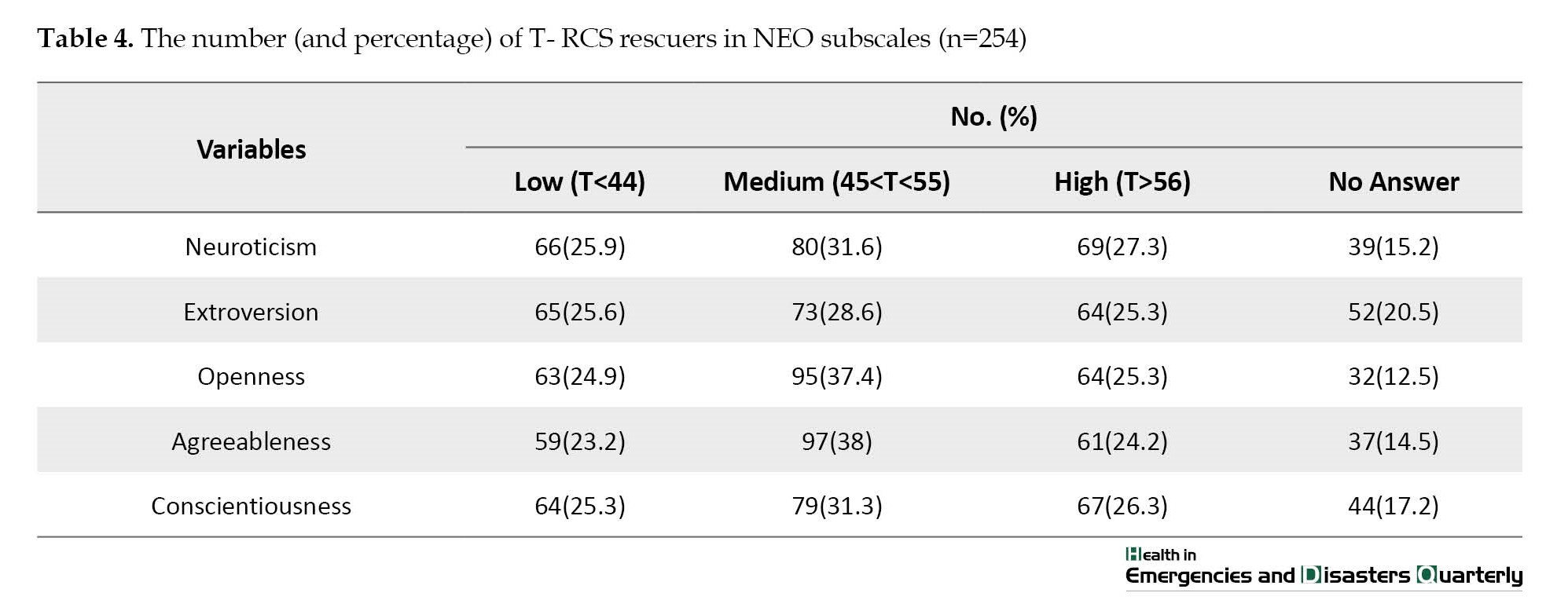

In the rescuers who answered the questions related to the subscales of the NEO questionnaire, 31.6% in the index of neuroticism, 28.6% in the index of extroversion, 37.4% in the index of openness, 38% in the index of agreeableness, and 31.3% in the index of conscientiousness had an average score, all of which were related to the highest frequency in these subscales (Table 4).

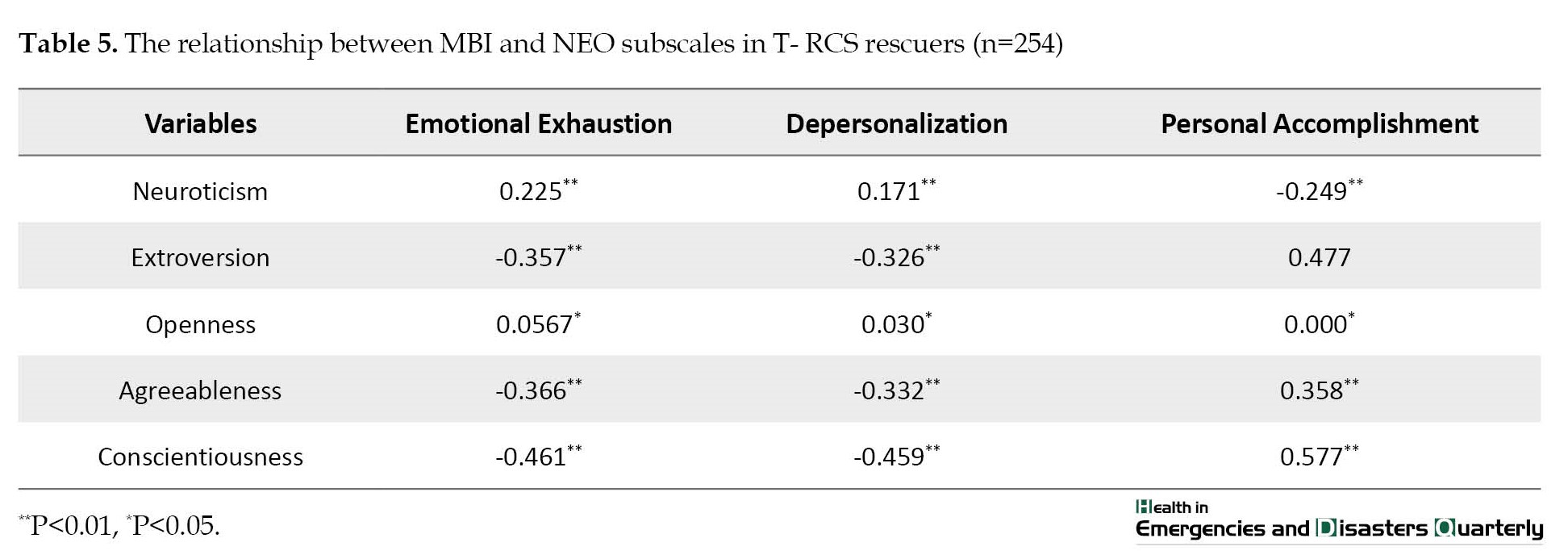

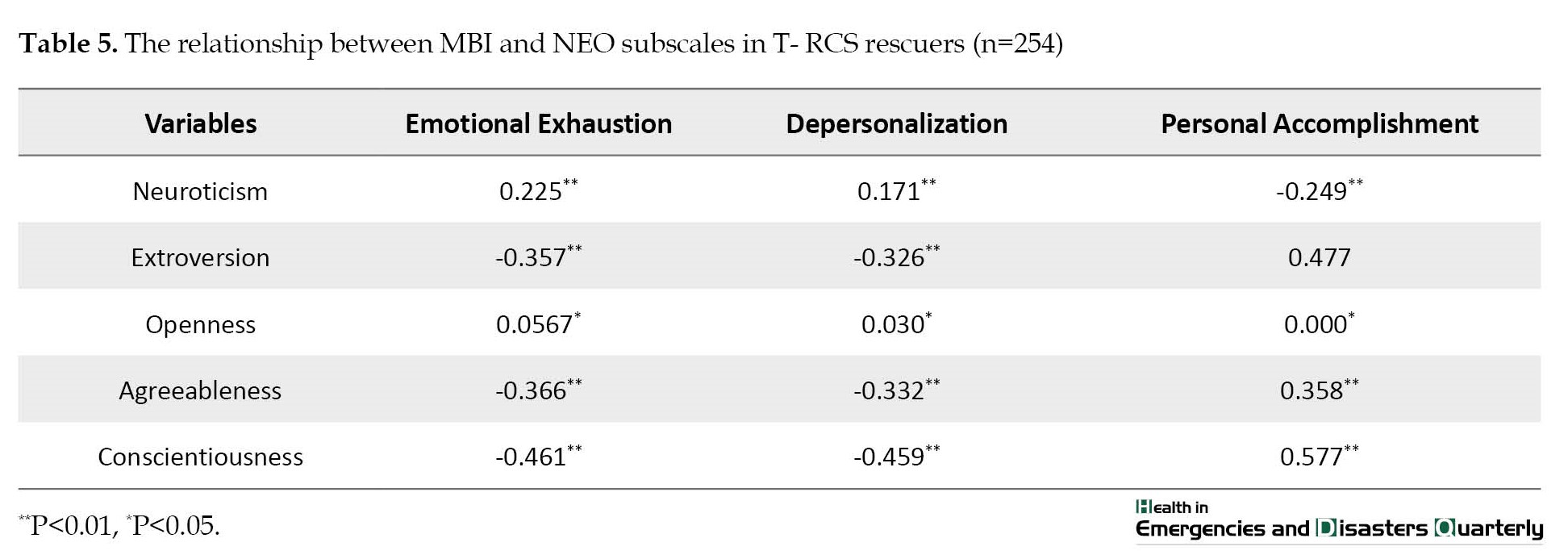

The Pearson correlation test was used to investigate the relationship between burnout subscales and the personality variables of neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. According to the results of this research, a significant positive relationship was observed between the subscale of emotional exhaustion and also the subscale of depersonalization with neuroticism. On the other hand, a significant negative relationship was observed between the emotional exhaustion subscale and the depersonalization subscale with extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. No relationship was found between the emotional exhaustion subscale and the depersonalization subscale with openness. A significant negative relationship was observed between the subscale of personal accomplishment and neuroticism. However, a significant positive relationship was observed between the subscale of personal accomplishment with extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. No relationship was found between the subscale of personal accomplishment and openness (Table 5).

To answer the question of whether a significant difference is observed in the degree of burnout among the groups of rescuers who are different in terms of personality traits, using the one-way analysis of variance, the significance of the difference in the mean scores of the burnout subscales between different groups of rescuers was employed. Then, to find out between which groups of rescuers, this significant difference is observed in the means, the Tukey follow-up test was performed.

A significant difference was observed in the average score of emotional exhaustion among the groups of rescuers who were different in terms of the degree of neuroticism (P=0.001, F(2, 225)=7.53). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with a low level of neuroticism had less emotional exhaustion compared to the other two groups. Emotional exhaustion was not significantly different in the two groups of rescuers with medium and high levels of neuroticism.

Also, a significant difference was observed in the mean depersonalization score between rescuer groups that differed in terms of the degree of neuroticism (P=0.007, F(2, 223)=5.06). In the follow-up test, the mean depersonalization score of rescuers who were in the group with a low level of neuroticism was significantly lower compared to the group with medium and high levels of neuroticism; however, the average score of depersonalization in two-rescuer groups with a medium and high level of neuroticism was not significantly different.

The mean score of personal accomplishment was also significantly different among rescuer groups that differed in terms of the degree of neuroticism (P=0.001, F(2, 224)=8.58). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with a low level of neuroticism had a higher sense of personal accomplishment compared to the other two groups. The feeling of personal accomplishment in the two groups of rescuers with medium and high levels of neuroticism was not significantly different.

Accordingly, obtaining lower scores in neuroticism can cause less emotional exhaustion, milder depersonalization, and a greater sense of personal accomplishment in rescuers. In other words, rescuers who score high in neuroticism are more prone to burnout.

Based on the results of this research, a significant difference was observed in the average score of emotional exhaustion among rescuer groups in terms of extroversion level (P=0.001, F(2, 212)=19.76). In the follow-up test, rescuers who were in the group with a low level of extroversion (i.e. were more introverted) had more emotional exhaustion compared to the other two groups. No significant difference was observed between emotional exhaustion in the two groups of rescuers with medium and high extroversion levels.

Also, a significant difference was observed in the mean score of depersonalization among rescuer groups in terms of the level of extroversion (P=0.001, F(2, 220)=17.50). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with low extroversion level (i.e. they were more introverted) had a higher average depersonalization score than the other two groups. The mean depersonalization score in two-rescuer groups with a medium and high extroversion level was not significantly different.

On the other hand, a significant difference was observed in the mean score of personal accomplishment among rescuer groups in terms of the level of extroversion (P=0.001, F(2, 209)=27.90). In the follow-up test, rescuers who were in the group with a low level of extroversion (i.e. they were more introverted) had a lower sense of personal accomplishment compared to the other two groups. The sense of personal accomplishment in the rescuer group with a medium extraversion level was significantly lower than in the rescuer group with a high extraversion level.

Hence, obtaining higher scores in extroversion can cause less emotional exhaustion, milder depersonalization, and a greater sense of personal accomplishment in rescuers. In other words, rescuers who score low in extroversion are more prone to burnout.

No significant difference was observed in the degree of burnout between the groups of rescuers who differed in terms of the personality trait of openness.

According to the results of this study, a significant difference was observed in the mean score of emotional exhaustion among the groups of rescuers who were different in terms of agreeableness (P=0.001, F(2, 227)=19.60). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with a low level of agreeableness had more emotional exhaustion compared to the other two groups. Emotional exhaustion in the rescuer group with a medium agreeableness level was significantly higher than in the rescuer group with a high agreeableness level.

A significant difference was observed in the mean depersonalization score among rescue groups that differed in terms of agreeableness level (P=0.001, F(2, 237)=17.18). In the follow-up test, rescuers in the group with a low level of agreeableness had a higher mean depersonalization score than the other two groups. The mean depersonalization score in the rescuer group with a medium level of agreeableness was not significantly different from the mean score in the rescuer group with a high level of agreeableness.

A significant difference was observed in the mean score of personal accomplishment among rescuer groups who in terms of agreeableness level differed (P=0.001, F(2, 227)=19.29). In the follow-up test, the rescuers placed in the group with a low level of agreeableness had a lower sense of personal accomplishment than the other two groups. The sense of personal accomplishment in the rescuer group with a medium agreeable level was significantly lower than in the rescuer group with a high agreeable level.

As a result, higher scores on agreeableness can lead to less emotional exhaustion, milder depersonalization, and a greater sense of personal accomplishment in rescuers. In other words, rescuers who score low on agreeableness are more prone to burnout.

The results of this research showed a significant difference in the mean score of emotional exhaustion among the groups of rescuers who were different in terms of conscientiousness (P=0.001, F(2, 221)=22.87). In the follow-up test, the rescuers in the group with a low level of conscientiousness had more emotional exhaustion than the other two groups. Emotional exhaustion was significantly higher in the group of rescuers with a medium level of conscientiousness than in the group of rescuers with a high level of conscientiousness.

Also, a significant difference was observed in the mean depersonalization score among rescuer groups in terms of the level of conscientiousness (P=0.001, F(2, 230)=25.76). In the follow-up test, the rescuers in the group with a low level of conscientiousness had a higher mean depersonalization score than the other two groups. The mean score of depersonalization in the rescuer group with an average level of conscientiousness was not significantly different from the mean score in the rescuer group with a high level of conscientiousness.

A significant difference was observed in the mean score of personal accomplishment among rescuer groups in terms of level of conscientiousness (P=0.001, F(2, 221)=37.01). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with a low level of conscientiousness had a lower sense of personal accomplishment compared to the other two groups. The feeling of personal accomplishment in the group of rescuers with a medium level of conscientiousness was significantly lower than in the group of rescuers with a high level of conscientiousness.

As a result, obtaining higher scores in conscientiousness can lead to less emotional exhaustion, milder depersonalization, and a greater sense of personal accomplishment in rescuers. In other words, rescuers who score low on conscientiousness are more prone to burnout.

Discussion

This study showed a significant positive relationship between neuroticism and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in the rescuers of the T- RCS, Iran, and a significant negative relationship between neuroticism and personal accomplishment. Accordingly, the rescuers who scored higher on neuroticism suffered more burnout.

Similar to the results of our research, regarding the relationship between neuroticism and burnout, Roloff et al. [14], and Kok et al. [15] showed that people who get a high neuroticism score may feel more emotional exhaustion, reduced personal accomplishment, and depersonalization. De la Fuente-Solana et al. [16] also demonstrated in their research that subjects who score high in terms of neuroticism experience a higher level of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

In addition, our research showed a significant negative relationship between extroversion and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and a significant positive relationship between extroversion and personal accomplishment. In other words, those rescuers of the T- RCS, Iran, who scored higher in the extroversion trait, are at a lower level of burnout. Li and Xu [17] and Chen and Hsu [18] showed a negative correlation between extroversion and emotional exhaustion. Stephens [19] also found this negative relationship between extroversion and depersonalization. In addition, Lopez-Nunez et al. reported a positive correlation between extroversion and personal accomplishment [20].

In the rescuers of the T- RCS, no significant relationship was found between openness and any of the burnout components; however, in the study by De la Fuente-Solana et al. a significant positive relationship was found between openness and personal accomplishment [16]. Also, in a study by Mahoney et al. a significant negative relationship was found between openness and burnout [21].

Among the rescuers of the T- RCS, among the five big personality factors, conscientiousness had the strongest relationship with burnout components. In these rescuers, a significant negative relationship was observed between conscientiousness and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and a significant positive relationship between conscientiousness and personal accomplishment. In other words, the rescuers who scored higher in the conscientiousness factor were at a lower level of burnout. Bhowmick and Mulla [22] also found a negative relationship between agreeableness and personal accomplishment. Saboori and Pishghadam [23] also reported a negative relationship between conscientiousness and depersonalization in a study.

A significant negative relationship was observed between agreeableness with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in rescuers of the T- RCS, and a positive significant relationship with personal accomplishment. That is, rescuers who scored higher in agreeableness were at a lower level of burnout. Bhowmick and Mulla [22] also showed a negative relationship between agreeableness and emotional exhaustion and a positive relationship between agreeableness and personal accomplishment. Listopad et al. [24] also showed a negative relationship between agreeableness and depersonalization in a study.

In a systematic review of 83 different studies on the relationship between burnout and personality traits by Angelini [25], it was found that higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of agreeableness, conscientiousness, extroversion, and openness are related to higher levels of burnout. The result of this systematic review confirms the results of our study about rescuers.

According to the results of our study, it seems that the personality traits of rescuers have a visible effect on their burnout. Rescuers with a low score in the traits of neuroticism and a high score in the traits of extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness feel less emotional exhaustion and suffer less depersonalization. On the other hand, these rescuers have a higher sense of personal accomplishment. In other words, these rescuers suffer less burnout.

In several studies, we can observe how scientific evidence shows the relationship between burnout and personality traits that are not completely defined. In this regard, Guthier’s meta-analysis [26] also emphasizes the need to expand job stress theories, focusing more on the role of personality in burnout. The results of our study, despite the similarities and differences with the results of other studies, confirm the need to develop theories that highlight the role of personality in burnout.

Conclusion

This study showed that rescuers who score high in neuroticism and low in extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness in the personality test are more prone to burnout. Therefore, in selecting people for the rescue profession and other necessary qualifications for this profession, people who score low on the personality test, neuroticism, and high scores in extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness are selected. The result of such selection can be less burnout for rescuers and providing better services to individuals injured in accidents and disasters.

Study limitations

In this research, only the rescuers of the T- RCS in Iran were studied. Due to the difference in the access of these rescuers to support facilities compared to other rescuers of the Red Crescent Society in other provinces, the degree of burnout in the studied rescuers may differ from the rescuers of other provinces. Also, considering that a month before this study was conducted, natural accidents and disasters had not happened in Tehran Province, and the rescuers were only involved in man-made accidents and disasters in this one month only; they may have experienced a different degree of burnout with the rescuers who have been involved in natural disasters and accidents. In addition, disaster rescuers from other related institutions were not included in this study.

All the rescuers of Red Crescent Society rescue centers in Tehran Province are men, and the subjects investigated in this study were all men. Therefore, the generalization of the results of this study to women rescuers in accidents and disasters should be done with caution.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and how to conduct it. They also ensured the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Data collection and writing the original draft: Shahin Fathi; Study design, data analysis, review and editing: Mehdi Najafi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate all the rescuers who participated in this study.

References

Bradley proposed burnout as a psychological phenomenon for the first time; however, the American psychiatrist, Herbert Freudenberger, is regarded as the originator of the concept, who described this syndrome in full detail in his influential article in 1974 entitled, "employee burnout". as a result, it provided the ground for its introduction [1]. Later, Maslach developed the concept of burnout and presented a multi-dimensional model of it [2]. Accordingly, burnout is a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. Emotional exhaustion is characterized by a lack of energy and includes feelings of disinterest, fear of returning to work, helplessness, hopelessness, dissatisfaction, and feeling trapped at work. In this case, the person feels that their emotional resources have been emptied in such a way that they can no longer continue fulfilling their responsibilities toward clients as in the past. Emotional exhaustion is the main dimension related to stress in burnout. Depersonalization is related to the negative attitude toward others and the feeling of separation and alienation from them. The feeling of alienation can show itself by withdrawing from clients and customers, physical separation in interactions, absence from work, late arrival, and excessive use of jokes. Depersonalization shows the interpersonal dimension of burnout [2]. The last component of burnout is reduced personal accomplishment. This is related to the feeling of incompetence and lack of productivity at work. The sense of reduced efficiency can be reinforced by the feeling of inadequacy to help clients and customers. This feeling leads to a person feeling defeated. Reduced personal accomplishment shows a person's tendency to negatively evaluate themselves. The personal accomplishment component shows the self-assessment dimension of burnout [3].

It is usually assumed that rescuers know what to do in any rescue situation. This belief leads to the thinking that the savior is a powerful person with sufficient physical and mental resources, can be easily compatible with what happened, and does not experience any problems in the face of accidents and disasters. Various studies indicate the risk of rescuers suffering from emotional and psychological problems and complications [4, 5]. The amount of mental pressure of a rescuer depends on various variables. Among them, we can mention the rescuers' coping and adaptation strategies and mechanisms, their personality variables, previous experiences, the severity and number of damages and injuries from accidents and disasters, in addition to many other cultural and social factors [6]. Burnout in rescuers of accidents and disasters can affect the health of victims by affecting their performance. On the other hand, paying less attention to personality traits in the selection of rescuers may cause more burnout in them. To the best of our knowledge, no study was conducted in Iran to examine the relationship between burnout and personality traits in rescuers. Hence, this study examines the relationship between burnout and some of their personality traits based on the research conducted on the rescuers of the Red Crescent Society of Tehran Province (T- RCS), Iran. With the results of this study, appropriate criteria can be provided for the selection of rescuers in this regard.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional correlational study conducted in December 2022. In this research, the correlation research design was used to determine whether a relationship exists between the burnout of rescuers and their personality traits. The studied population included all the rescuers of the 16 branches of the T- RCS, who work in 19 rescue centers. Rescuers are people who attend the scene of the accident through Red Crescent rescue bases and provide aid to the victims of accidents. The sample size was 414 people. To determine the minimum required sample size, the Morgan table was used (for more accuracy and to ensure the completion of the required questionnaires, a larger sample size was considered). Due to the clarity of the sampling framework, the samples were randomly selected from the statistical population, and out of 270 distributed questionnaires, after removing the incomplete questionnaires, 254 questionnaires were analyzed. Considering that all the rescuers at the rescue centers are men, the subjects in this study were all men. These rescuers included volunteers and rescue personnel of the T- RCS, Iran.

Since no natural disaster (such as flood, earthquake, etc.) occurred during the month before this research, all the incidents that these rescuers faced during the month before the research were unnatural disasters (such as road accidents or mountain accidents).

Meslach burnout inventory (MBI) was used to evaluate the burnout of the participants in this study. This questionnaire is a gold standard measurement tool to measure burnout and includes three independent measurement subscales. The emotional exhaustion subscale evaluates being tired of work and emotional overactivity. The depersonalization subscale examines the degree of insensitivity. And, the lack of personality and personal accomplishment subscale investigates a person’s sense of adequacy and work success. The questionnaire has 22 items which are divided into three subscales. For each item in terms of frequency, a 7-point scale is considered, according to the respondent’s experience with that item, they choose one (from 0=never to 6=every day). Nine items are related to the subscale of emotional exhaustion, which evaluates prolonged emotions and fatigue caused by a person’s work. Five items are related to the depersonalization subscale, which measures apathy toward the services provided to the recipients of these services. A moderate correlation is observed between these two subscales, although each one measures a different aspect of burnout. For both subscales of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, high scores indicate high levels of burnout. Eight items are related to the subscale of personal accomplishment, which measures the sense of competence and success in working with people. Unlike the other two subscales, low scores in this subscale indicate high levels of burnout. The subscale of personal efficiency is independent from the other two subscales. In other words, the correlation between the subscale of personal efficiency and the other two subscales is weak. The completed questionnaire of each respondent is graded based on the instructions for scoring each subscale. The scores of each subscale should be calculated separately and should not be added together and expressed as a single score. Therefore, three scores are calculated for each respondent. Each score can be expressed as low, medium, and high based on the classification [7].

In MBI, the minimum score for each subscale is zero and the maximum score for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment are 54, 30, and 48, respectively. In this questionnaire, emotional exhaustion scores between 0 and 16 are considered low level, while scores from 17 to 26 are considered medium level, and more than 27 is regarded as high level. We consider the depersonalization score between 0 and 6 as a low level, between 7 and 12 as a medium level, and more than 13 as a high level. In the case of personal accomplishment, the scale is reversed. Then, if the personal accomplishment score is above 37, it is regarded as a low level, if it is between 31 and 36, it is considered medium level and if it is between zero and 30, it is considered high level [8]. A high score of emotional exhaustion a high score of depersonalization or a low score of personal accomplishment show high levels of burnout.

To examine the reliability of this questionnaire, Maslash and Jackson evaluated the internal consistency of the questionnaire with the Cronbach α coefficient, which showed a reliability coefficient of 0.83. They also showed the validity of this questionnaire by examining its convergent validity and discriminant validity [9]. In a study conducted in Iran, the reliability of the subscales of the questionnaire (Persian version) was between 0.80 and 0.94. This study has also shown that the content validity ratio and content validity index in the Persian version is 0.87, which shows that all the questions in the questionnaire have high content validity [10].

In this research, the investigated personality traits are based on a well-known theory called the five-factor model of personality, which is also known as the big five factors. The five factors are neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness [11].

The short form of the neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (NEO) questionnaire was used to measure the mentioned personality traits in the rescuers of the T- RCS. This questionnaire is a type of personality trait self-assessment questionnaire that is based on the five-factor model. This questionnaire contains 60 questions. In this questionnaire, each 12 questions is for one feature, and each feature, the minimum score is zero while the maximum score is 48.

Regarding the reliability of the short-form of NEO, studies show good internal stability for its subscales. For example, McCrae and Costa reported the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.68 for agreeableness and 0.86 for neuroticism. Holden also reported the Cronbach α coefficient of these 5 factors in the range of 0.76 (for openness) to 0.87 (for neuroticism). About the validity of the short-form NEO subscales, McCrae and Costa have stated that the shortened NEO tool corresponds exactly with its full form, in such a way that the subscales of the short form correlate higher than 0.68 with the subscales of the full form [12].

The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire have been conducted in Iran. In the study by Anisi et al. the results of reliability analysis using the Cronbach α method showed that the characteristics of conscientiousness, neuroticism, agreeableness, extroversion, and openness were 0.83, 0.80, 0.60, 0.58, and 0.39, respectively. In addition, the subscales of this questionnaire had a correlation coefficient of 0.47 to 0.68 with the corresponding subscales in the Eysenk personality questionnaire [13].

Results

Among the 270 distributed questionnaires, 254 questionnaires were analyzed. Considering that all the rescuers at the rescue centers are men, the subjects in this study were all male. Most respondents were between 18 and 23 years old, and in terms of education, most of them had a diploma. Most respondents were volunteers and often had between 1 and 5 years of rescue experience (Table 1).

To check the level of burnout in rescuers, the average subscales of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment were measured in the subjects (Table 2).

Additionally, in terms of emotional exhaustion, 70.7% of rescuers (the highest frequency) were in the group with a low level of burnout, and only 2.7% of them (the lowest frequency) were in the group with a high level of burnout. Meanwhile, 11.4% of rescuers experienced a moderate level of burnout and 15.2% of them did not fully answer the questions in this section.

Also, in terms of depersonalization, 68% of rescuers (the highest frequency) were in the group with a low level of burnout. Meanwhile, 7.1% of them were in the group with a high level (lowest frequency) and 14.8% of them were in the group with a medium level of burnout. Nevertheless, 10.1% of the respondents did not fully answer the questions in this section.

In terms of personal accomplishment, 32.7% of rescuers (the highest frequency) were in the group with a high level of burnout, 23.2% of them were in the group with an average level of burnout, and 29.3% of them were in the group with a low level of burnout. Also, 14.8% of them did not fully answer the questions in this section.

In examining the subscales of the NEO questionnaire, the highest mean score of the subjects was related to the conscientiousness personality trait (34.08±8.32), and the lowest mean score was related to the neuroticism personality trait (20.20±6.14) (Table 3).

To categorize the scores related to the five big personality factors, first, the raw scores of each factor were converted into Z scores, and then the T score of each was calculated (T=10+Z50). Subsequently, the obtained scores were classified into three groups low score (T≥44), medium score (T≥45≥55), and high score (T≤56). They were analyzed based on the classified data.

In the rescuers who answered the questions related to the subscales of the NEO questionnaire, 31.6% in the index of neuroticism, 28.6% in the index of extroversion, 37.4% in the index of openness, 38% in the index of agreeableness, and 31.3% in the index of conscientiousness had an average score, all of which were related to the highest frequency in these subscales (Table 4).

The Pearson correlation test was used to investigate the relationship between burnout subscales and the personality variables of neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. According to the results of this research, a significant positive relationship was observed between the subscale of emotional exhaustion and also the subscale of depersonalization with neuroticism. On the other hand, a significant negative relationship was observed between the emotional exhaustion subscale and the depersonalization subscale with extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. No relationship was found between the emotional exhaustion subscale and the depersonalization subscale with openness. A significant negative relationship was observed between the subscale of personal accomplishment and neuroticism. However, a significant positive relationship was observed between the subscale of personal accomplishment with extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. No relationship was found between the subscale of personal accomplishment and openness (Table 5).

To answer the question of whether a significant difference is observed in the degree of burnout among the groups of rescuers who are different in terms of personality traits, using the one-way analysis of variance, the significance of the difference in the mean scores of the burnout subscales between different groups of rescuers was employed. Then, to find out between which groups of rescuers, this significant difference is observed in the means, the Tukey follow-up test was performed.

A significant difference was observed in the average score of emotional exhaustion among the groups of rescuers who were different in terms of the degree of neuroticism (P=0.001, F(2, 225)=7.53). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with a low level of neuroticism had less emotional exhaustion compared to the other two groups. Emotional exhaustion was not significantly different in the two groups of rescuers with medium and high levels of neuroticism.

Also, a significant difference was observed in the mean depersonalization score between rescuer groups that differed in terms of the degree of neuroticism (P=0.007, F(2, 223)=5.06). In the follow-up test, the mean depersonalization score of rescuers who were in the group with a low level of neuroticism was significantly lower compared to the group with medium and high levels of neuroticism; however, the average score of depersonalization in two-rescuer groups with a medium and high level of neuroticism was not significantly different.

The mean score of personal accomplishment was also significantly different among rescuer groups that differed in terms of the degree of neuroticism (P=0.001, F(2, 224)=8.58). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with a low level of neuroticism had a higher sense of personal accomplishment compared to the other two groups. The feeling of personal accomplishment in the two groups of rescuers with medium and high levels of neuroticism was not significantly different.

Accordingly, obtaining lower scores in neuroticism can cause less emotional exhaustion, milder depersonalization, and a greater sense of personal accomplishment in rescuers. In other words, rescuers who score high in neuroticism are more prone to burnout.

Based on the results of this research, a significant difference was observed in the average score of emotional exhaustion among rescuer groups in terms of extroversion level (P=0.001, F(2, 212)=19.76). In the follow-up test, rescuers who were in the group with a low level of extroversion (i.e. were more introverted) had more emotional exhaustion compared to the other two groups. No significant difference was observed between emotional exhaustion in the two groups of rescuers with medium and high extroversion levels.

Also, a significant difference was observed in the mean score of depersonalization among rescuer groups in terms of the level of extroversion (P=0.001, F(2, 220)=17.50). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with low extroversion level (i.e. they were more introverted) had a higher average depersonalization score than the other two groups. The mean depersonalization score in two-rescuer groups with a medium and high extroversion level was not significantly different.

On the other hand, a significant difference was observed in the mean score of personal accomplishment among rescuer groups in terms of the level of extroversion (P=0.001, F(2, 209)=27.90). In the follow-up test, rescuers who were in the group with a low level of extroversion (i.e. they were more introverted) had a lower sense of personal accomplishment compared to the other two groups. The sense of personal accomplishment in the rescuer group with a medium extraversion level was significantly lower than in the rescuer group with a high extraversion level.

Hence, obtaining higher scores in extroversion can cause less emotional exhaustion, milder depersonalization, and a greater sense of personal accomplishment in rescuers. In other words, rescuers who score low in extroversion are more prone to burnout.

No significant difference was observed in the degree of burnout between the groups of rescuers who differed in terms of the personality trait of openness.

According to the results of this study, a significant difference was observed in the mean score of emotional exhaustion among the groups of rescuers who were different in terms of agreeableness (P=0.001, F(2, 227)=19.60). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with a low level of agreeableness had more emotional exhaustion compared to the other two groups. Emotional exhaustion in the rescuer group with a medium agreeableness level was significantly higher than in the rescuer group with a high agreeableness level.

A significant difference was observed in the mean depersonalization score among rescue groups that differed in terms of agreeableness level (P=0.001, F(2, 237)=17.18). In the follow-up test, rescuers in the group with a low level of agreeableness had a higher mean depersonalization score than the other two groups. The mean depersonalization score in the rescuer group with a medium level of agreeableness was not significantly different from the mean score in the rescuer group with a high level of agreeableness.

A significant difference was observed in the mean score of personal accomplishment among rescuer groups who in terms of agreeableness level differed (P=0.001, F(2, 227)=19.29). In the follow-up test, the rescuers placed in the group with a low level of agreeableness had a lower sense of personal accomplishment than the other two groups. The sense of personal accomplishment in the rescuer group with a medium agreeable level was significantly lower than in the rescuer group with a high agreeable level.

As a result, higher scores on agreeableness can lead to less emotional exhaustion, milder depersonalization, and a greater sense of personal accomplishment in rescuers. In other words, rescuers who score low on agreeableness are more prone to burnout.

The results of this research showed a significant difference in the mean score of emotional exhaustion among the groups of rescuers who were different in terms of conscientiousness (P=0.001, F(2, 221)=22.87). In the follow-up test, the rescuers in the group with a low level of conscientiousness had more emotional exhaustion than the other two groups. Emotional exhaustion was significantly higher in the group of rescuers with a medium level of conscientiousness than in the group of rescuers with a high level of conscientiousness.

Also, a significant difference was observed in the mean depersonalization score among rescuer groups in terms of the level of conscientiousness (P=0.001, F(2, 230)=25.76). In the follow-up test, the rescuers in the group with a low level of conscientiousness had a higher mean depersonalization score than the other two groups. The mean score of depersonalization in the rescuer group with an average level of conscientiousness was not significantly different from the mean score in the rescuer group with a high level of conscientiousness.

A significant difference was observed in the mean score of personal accomplishment among rescuer groups in terms of level of conscientiousness (P=0.001, F(2, 221)=37.01). In the follow-up test, the rescuers who were in the group with a low level of conscientiousness had a lower sense of personal accomplishment compared to the other two groups. The feeling of personal accomplishment in the group of rescuers with a medium level of conscientiousness was significantly lower than in the group of rescuers with a high level of conscientiousness.

As a result, obtaining higher scores in conscientiousness can lead to less emotional exhaustion, milder depersonalization, and a greater sense of personal accomplishment in rescuers. In other words, rescuers who score low on conscientiousness are more prone to burnout.

Discussion

This study showed a significant positive relationship between neuroticism and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in the rescuers of the T- RCS, Iran, and a significant negative relationship between neuroticism and personal accomplishment. Accordingly, the rescuers who scored higher on neuroticism suffered more burnout.

Similar to the results of our research, regarding the relationship between neuroticism and burnout, Roloff et al. [14], and Kok et al. [15] showed that people who get a high neuroticism score may feel more emotional exhaustion, reduced personal accomplishment, and depersonalization. De la Fuente-Solana et al. [16] also demonstrated in their research that subjects who score high in terms of neuroticism experience a higher level of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

In addition, our research showed a significant negative relationship between extroversion and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and a significant positive relationship between extroversion and personal accomplishment. In other words, those rescuers of the T- RCS, Iran, who scored higher in the extroversion trait, are at a lower level of burnout. Li and Xu [17] and Chen and Hsu [18] showed a negative correlation between extroversion and emotional exhaustion. Stephens [19] also found this negative relationship between extroversion and depersonalization. In addition, Lopez-Nunez et al. reported a positive correlation between extroversion and personal accomplishment [20].

In the rescuers of the T- RCS, no significant relationship was found between openness and any of the burnout components; however, in the study by De la Fuente-Solana et al. a significant positive relationship was found between openness and personal accomplishment [16]. Also, in a study by Mahoney et al. a significant negative relationship was found between openness and burnout [21].

Among the rescuers of the T- RCS, among the five big personality factors, conscientiousness had the strongest relationship with burnout components. In these rescuers, a significant negative relationship was observed between conscientiousness and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and a significant positive relationship between conscientiousness and personal accomplishment. In other words, the rescuers who scored higher in the conscientiousness factor were at a lower level of burnout. Bhowmick and Mulla [22] also found a negative relationship between agreeableness and personal accomplishment. Saboori and Pishghadam [23] also reported a negative relationship between conscientiousness and depersonalization in a study.

A significant negative relationship was observed between agreeableness with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in rescuers of the T- RCS, and a positive significant relationship with personal accomplishment. That is, rescuers who scored higher in agreeableness were at a lower level of burnout. Bhowmick and Mulla [22] also showed a negative relationship between agreeableness and emotional exhaustion and a positive relationship between agreeableness and personal accomplishment. Listopad et al. [24] also showed a negative relationship between agreeableness and depersonalization in a study.

In a systematic review of 83 different studies on the relationship between burnout and personality traits by Angelini [25], it was found that higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of agreeableness, conscientiousness, extroversion, and openness are related to higher levels of burnout. The result of this systematic review confirms the results of our study about rescuers.

According to the results of our study, it seems that the personality traits of rescuers have a visible effect on their burnout. Rescuers with a low score in the traits of neuroticism and a high score in the traits of extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness feel less emotional exhaustion and suffer less depersonalization. On the other hand, these rescuers have a higher sense of personal accomplishment. In other words, these rescuers suffer less burnout.

In several studies, we can observe how scientific evidence shows the relationship between burnout and personality traits that are not completely defined. In this regard, Guthier’s meta-analysis [26] also emphasizes the need to expand job stress theories, focusing more on the role of personality in burnout. The results of our study, despite the similarities and differences with the results of other studies, confirm the need to develop theories that highlight the role of personality in burnout.

Conclusion

This study showed that rescuers who score high in neuroticism and low in extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness in the personality test are more prone to burnout. Therefore, in selecting people for the rescue profession and other necessary qualifications for this profession, people who score low on the personality test, neuroticism, and high scores in extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness are selected. The result of such selection can be less burnout for rescuers and providing better services to individuals injured in accidents and disasters.

Study limitations

In this research, only the rescuers of the T- RCS in Iran were studied. Due to the difference in the access of these rescuers to support facilities compared to other rescuers of the Red Crescent Society in other provinces, the degree of burnout in the studied rescuers may differ from the rescuers of other provinces. Also, considering that a month before this study was conducted, natural accidents and disasters had not happened in Tehran Province, and the rescuers were only involved in man-made accidents and disasters in this one month only; they may have experienced a different degree of burnout with the rescuers who have been involved in natural disasters and accidents. In addition, disaster rescuers from other related institutions were not included in this study.

All the rescuers of Red Crescent Society rescue centers in Tehran Province are men, and the subjects investigated in this study were all men. Therefore, the generalization of the results of this study to women rescuers in accidents and disasters should be done with caution.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and how to conduct it. They also ensured the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Data collection and writing the original draft: Shahin Fathi; Study design, data analysis, review and editing: Mehdi Najafi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate all the rescuers who participated in this study.

References

- Schaufeli W, Enzmann D. Where does burnout come from? In: Schaufeli W, Enzmann D, editors. History and background: A critical analysis. London: CRC Press; 1998. [DOI:10.1201/9781003062745-1]

- Călin MF, Tasente T, Seucea A. The effects of burnout on the professional activity of teachers. Technium Social Sciences Journal. 2022; 34(1):430-40. [DOI:10.47577/tssj.v34i1.7156]

- Ozturk YE. A theoretical review of burnout syndrome and perspectives on burnout models. Bussecon Review of Social Sciences (2687-2285). 2020; 2(4):26-35. [DOI:10.36096/brss.v2i4.235]

- Young T, Pakenham KI, Chapman CM, Edwards MR. Predictors of mental health in aid workers: meaning, resilience, and psychological flexibility as personal resources for increased well being and reduced distress. Disasters. 2022; 46(4):974-1006. [DOI:10.1111/disa.12517] [PMID]

- Alzahrani Y. Risks to responders safety and mitigation strategies during rescue work in natural disasters: A scoping review [MSc thesis]. Cape Town: University of Cape Town; 2022. [Link]

- Theleritis C, Psarros C, Mantonakis L, Roukas D, Papaioannou A, et al. Coping and its relation to PTSD in Greek firefighters. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2020; 208(3):252-9. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001103] [PMID]

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. Burnout. In: Fink G, editor. Stress: Concepts, cognition, emotion, and behavior handbook of stress series. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2016. [DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800951-2.00044-3]

- Gaitan PE. Teacher Burnout Factors of Adherence to Behavioral Intervention [PhD dissertation]. Minnesota: University of Minnesota; 2009. [Link]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1981; 2(2):99-113. [DOI:10.1002/job.4030020205]

- Shamloo ZS, Hashemian SS, Khoshsima H, Shahverdi A, Khodadost M, Gharavi MM. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (general survey version) in Iranian population. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2017; 11(2):e8168. [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.8168]

- Babcock SE, Wilson CA. Big five model of personality. The Wiley encyclopedia of personality and individual differences: Personality processes and individual differences. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2020. [DOI:10.1002/9781119547174.ch186]

- McCrae RR, CostaPT. Empirical and theoretical status of the five-factor model of personality traits. In: Boyle GJ, Matthews G, Saklofske DH, editors. The SAGE handbook of personality theory and assessment, Personality theories and models. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2008. [DOI: 10.4135/9781849200462.n13]

- Anisi J. [Validity and reliability of NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) on university students (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 5(4):351-5. [Link]

- Roloff J, Kirstges J, Grund S, Klusmann U. How strongly is personality associated with burnout among teachers? A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review. 2022; 34:1613-50. [DOI:10.1007/s10648-022-09672-7]

- Kok N, Van Gurp J, van der Hoeven JG, Fuchs M, Hoedemaekers C, Zegers M. Complex interplay between moral distress and other risk factors of burnout in ICU professionals: findings from a cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2023; 32(4):225-34. [DOI:10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012239] [PMID]

- De la Fuente-Solana EI, Suleiman-Martos N, Velando-Soriano A, Cañadas-De la Fuente GR, Herrera-Cabrerizo B, Albendín-García L. Predictors of burnout of health professionals in the departments of maternity and gynaecology, and its association with personality factors: A multicentre study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021; 30(1-2):207-16. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.15541] [PMID]

- Li J, Xu S. Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Employee Voice: A Conservation of Resources Perspective. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11:1281. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01281] [PMID]

- Chen CF, Hsu YC. Taking a Closer Look at Bus Driver Emotional Exhaustion and Well-Being: Evidence from Taiwanese Urban Bus Drivers. Safety and Health at Work. 2020; 11(3):353-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.shaw.2020.06.002] [PMID]

- Stephens NM. A Correlational Model of Burnout and Personality among Clergy in the United States [PhD dissertation]. Michigan: Andrews University; 2020. [DOI:10.32597/dissertations/1721]

- López-Núñez MI, Rubio-Valdehita S, Diaz-Ramiro EM, Aparicio-García ME. Psychological Capital, Workload, and Burnout: What’s New? The Impact of Personal Accomplishment to Promote Sustainable Working Conditions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8124. [DOI:10.3390/su12198124]

- Mahoney CB, Lea J, Schumann PL, Jillson IA. Turnover, burnout, and job satisfaction of certified registered nurse anesthetists in the United States: Role of job characteristics and personality. AANA Journal. 2020; 88(1):39-48. [Link]

- Bhowmick S, Mulla Z. Who gets burnout and when? The role of personality, job control, and organizational identification in predicting burnout among police officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. 2021; 36:243-55. [DOI:10.1007/s11896-020-09407-w]

- Saboori F, Pishghadam, R. English language teachers’ burnout within the cultural dimensions framework. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. 2016; 25:677-87. [DOI:10.1007/s40299-016-0297-y]

- Listopad IW, Michaelsen MM, Werdecker L, Esch T. Bio-psycho-socio-Spirito-cultural factors of burnout: A systematic narrative review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021; 12:722862. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722862] [PMID]

- Angelini G. Big five model personality traits and job burnout: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychology. 2023; 11(1):49. [DOI:10.1186/s40359-023-01056-y] [PMID]

- Guthier C, Dormann C, Voelkle MC. Reciprocal efects between job stressors and burnout: a continuous time meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2020; 146:1146-73. [DOI:10.1037/bul0000304] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Relief teams

Received: 2023/09/22 | Accepted: 2023/11/17 | Published: 2024/04/1

Received: 2023/09/22 | Accepted: 2023/11/17 | Published: 2024/04/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |