Volume 9, Issue 2 (Winter 2024)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2024, 9(2): 137-144 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nasrabadi A N, Joolaee S, Navab E, Esmaeili M, Khalilabad T H, Shali M et al . Investigating the Use of White Lies During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2024; 9 (2) :137-144

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-536-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-536-en.html

Alireza Nikbakht Nasrabadi1

, Soodabeh Joolaee2

, Soodabeh Joolaee2

, Elham Navab3

, Elham Navab3

, Maryam Esmaeili3

, Maryam Esmaeili3

, Touraj Harati Khalilabad4

, Touraj Harati Khalilabad4

, Mahbobeh Shali *5

, Mahbobeh Shali *5

, Zahra Abbasi Dolatabadi1

, Zahra Abbasi Dolatabadi1

, Soodabeh Joolaee2

, Soodabeh Joolaee2

, Elham Navab3

, Elham Navab3

, Maryam Esmaeili3

, Maryam Esmaeili3

, Touraj Harati Khalilabad4

, Touraj Harati Khalilabad4

, Mahbobeh Shali *5

, Mahbobeh Shali *5

, Zahra Abbasi Dolatabadi1

, Zahra Abbasi Dolatabadi1

1- Department of Medical-Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., School of Nursing Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences Nosrat St., Tohid Sq., Tehran, IRAN 141973317

2- Nursing Care Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., School of Nursing Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences Nosrat St., Tohid Sq., Tehran, IRAN 141973317

3- Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., School of Nursing Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences Nosrat St., Tohid Sq., Tehran, IRAN 141973317

4- Department of Health Economy, School of Health Management and Information Science, Sardar Solimani Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., School of Nursing Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences Nosrat St., Tohid Sq., Tehran, IRAN 141973317

5- Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,mehraneshali@yahoo.com

2- Nursing Care Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., School of Nursing Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences Nosrat St., Tohid Sq., Tehran, IRAN 141973317

3- Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., School of Nursing Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences Nosrat St., Tohid Sq., Tehran, IRAN 141973317

4- Department of Health Economy, School of Health Management and Information Science, Sardar Solimani Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., School of Nursing Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences Nosrat St., Tohid Sq., Tehran, IRAN 141973317

5- Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 440 kb]

(972 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3452 Views)

Full-Text: (766 Views)

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) is the pandemic agent of COVID-19 disease that began in December 2019 in Wuhan, China [1, 2]. The intentional selection of the official name for the disease is aimed at preventing stigmatization. The term “co” represents corona, “vi” signifies virus, “d” denotes disease, and “19” denotes the year of the disease emergence (2019) [3].

In Iran, the initial case of COVID-19 was documented on February 19, 2019, in Qom City, Iran. Subsequently, the disease rapidly disseminated to neighboring provinces [2, 4]. Iran, being an Islamic country, adheres to principles that emphasize truthfulness, and individuals are encouraged to abstain from falsehoods, committing to honesty [5]. However, various emotional, professional, and cultural barriers may at times hinder the straightforward communication of accurate information by both healthcare providers and patients [5, 6, 7]. In such aforementioned situations, both healthcare providers and patients may find themselves resorting to the use of white lies as a means to manage the situation [8].

White lie, by definition, is an ethical decision without personal derive that is made in special circumstances, when people are faced with bitter truth, to protect one another against predictable harms [9]. To decide whether to present information or withhold the truth and use a white lie is an ethical challenge that requires knowledge of ethical principles [10, 11]. Alternatively, in complex situations, making an incorrect decision followed by inappropriate intervention could lead to adverse consequences for the patient, their family, or even the broader society. Engaging in dishonesty is not aligned with a person-centered approach. As such, preventing and managing this behavior necessitates interventions targeting its root causes. The utilization of white lies can be influenced by various factors, including cultural and social considerations [12]. Despite a search in the scientific literature, no study was found about the use of white lies in times of crisis. Nevertheless, there is a lack of comprehensive information regarding the specific circumstances that compel individuals to resort to white lies during a pandemic crisis. This study bridges this gap and investigates the experiences of patients with COVID-19, their families, and healthcare workers in employing white lies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative study was carried out from April to June 2020 in Tehran City, Iran. Purposeful sampling was used to select the participants from healthcare workers (physician and nurse) and patients with COVID-19 and their families in hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Willingness to participate in the study, having work experience in hospitals dealing with COVID-19 (for healthcare workers), having COVID-19 or caring for a patient with COVID-19 (for patient and their families), and being verbally capable of expressing personal experiences related to the study topic.

The data were collected using face-to-face individual and semi-structured interviews. Place of interviews were coordinated with the participants. An interview guide was used to ask questions about the participants’ experiences during the interview, including “have you ever experienced a situation during the COVID-19 pandemic?” “Where did you not want to or could not tell the truth to others?” “How did you use a white lie?” “Would you please explain more?”

Each interview lasted between 45 to 60 min. Data collection was continued until data saturation. Saturation in this research meant that no new code was extracted in the process of coding. Data analysis was conducted using the conventional content analysis approach, as proposed by Graneheim and Lundman [13]. Initially, the researchers listened to the interviews multiple times and subsequently transcribed them verbatim. The texts and accompanying field notes underwent a thorough review, with words, sentences, and paragraphs treated as conceptual units. They were then assigned specific codes. Data management was done using the MAXQDA software, version 12. The codes were compared in terms of similarities and differences and were classified. Trustworthiness was examined by the Guba and Lincoln criteria of credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability [14].

Credibility was enhanced through sustained engagement with the data throughout all phases, coupled with collaborative analysis. To conduct an external validation, preliminary findings were presented to a panel of experts at a seminar. Additionally, the participants in the study evaluated theme descriptions for a member check, further ensuring credibility, subsequently, and dependability.

To assess the transferability of the findings, we presented them to a diverse audience. Confirmability, requiring researcher neutrality, was maintained by documenting an audit trail, which elucidated the connection between the data, sources, and the derivation of conclusions and interpretations in this study.

Results

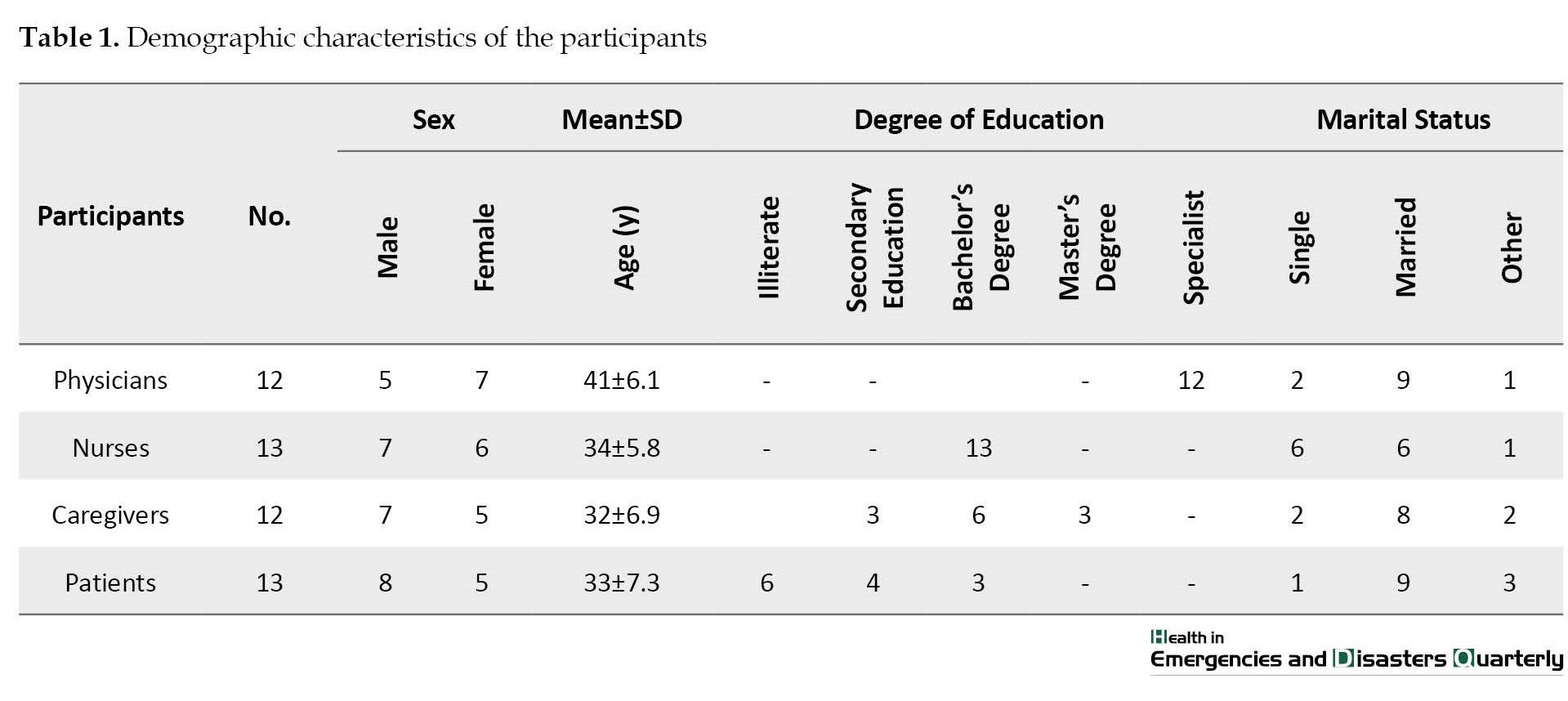

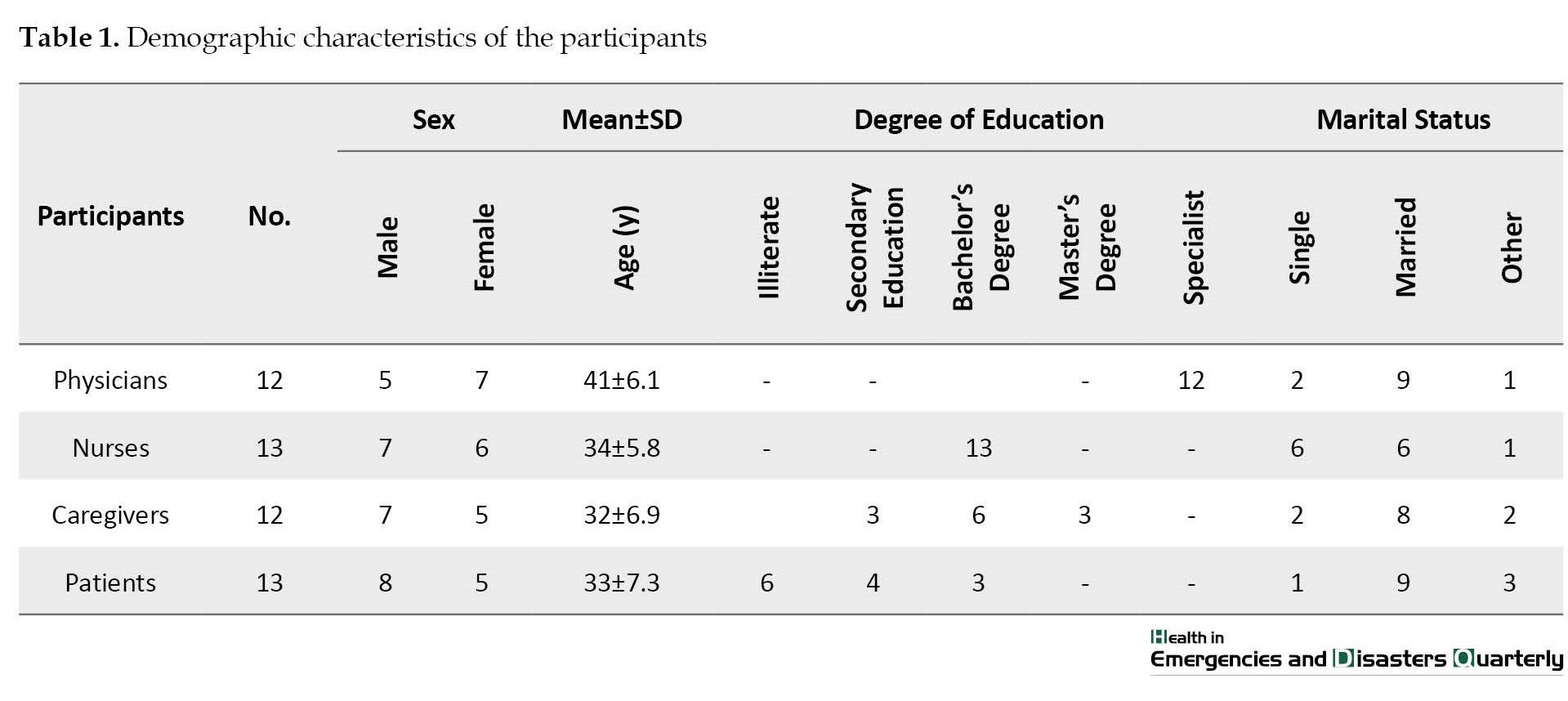

The participants consisted of 23 female and 27 male subjects with a mean age of 35±6.3 years. Also, 13 of the participants were patients with COVID-19 disease, 12 were family members of patients with COVID-19, and 25 were medical staff including physicians and nurses working in the treatment centers dedicated to COVID-19. All nurses had bachelor’s degrees and participating doctors had specialist degrees. Meanwhile, 6 people from the patient’s family had a bachelor’s degree, 3 people had a post-graduate degree, and 3 people had a secondary education. Also, 6 of the patients were illiterate, 3 had a bachelor’s degree, and 4 had a secondary education (Table 1).

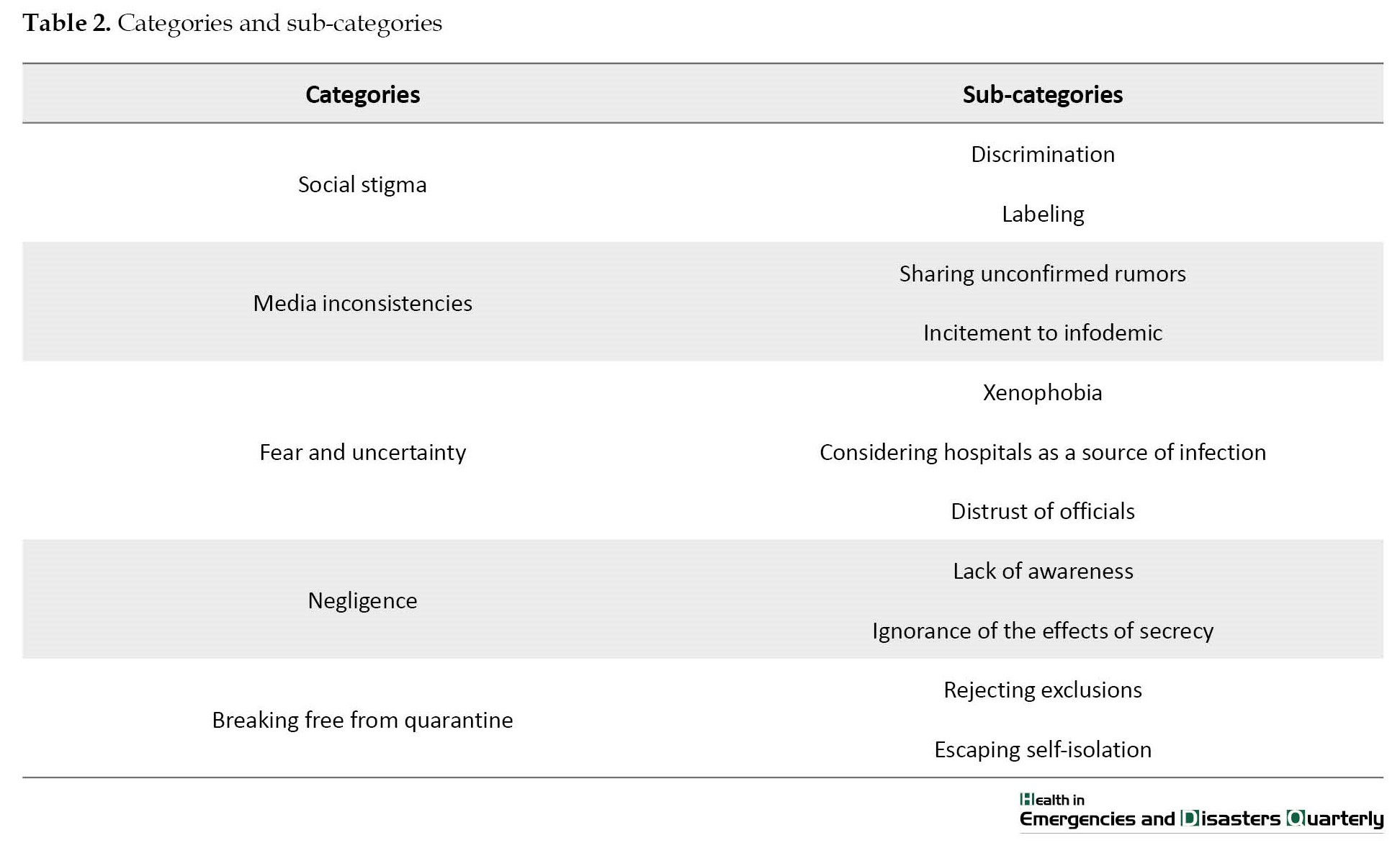

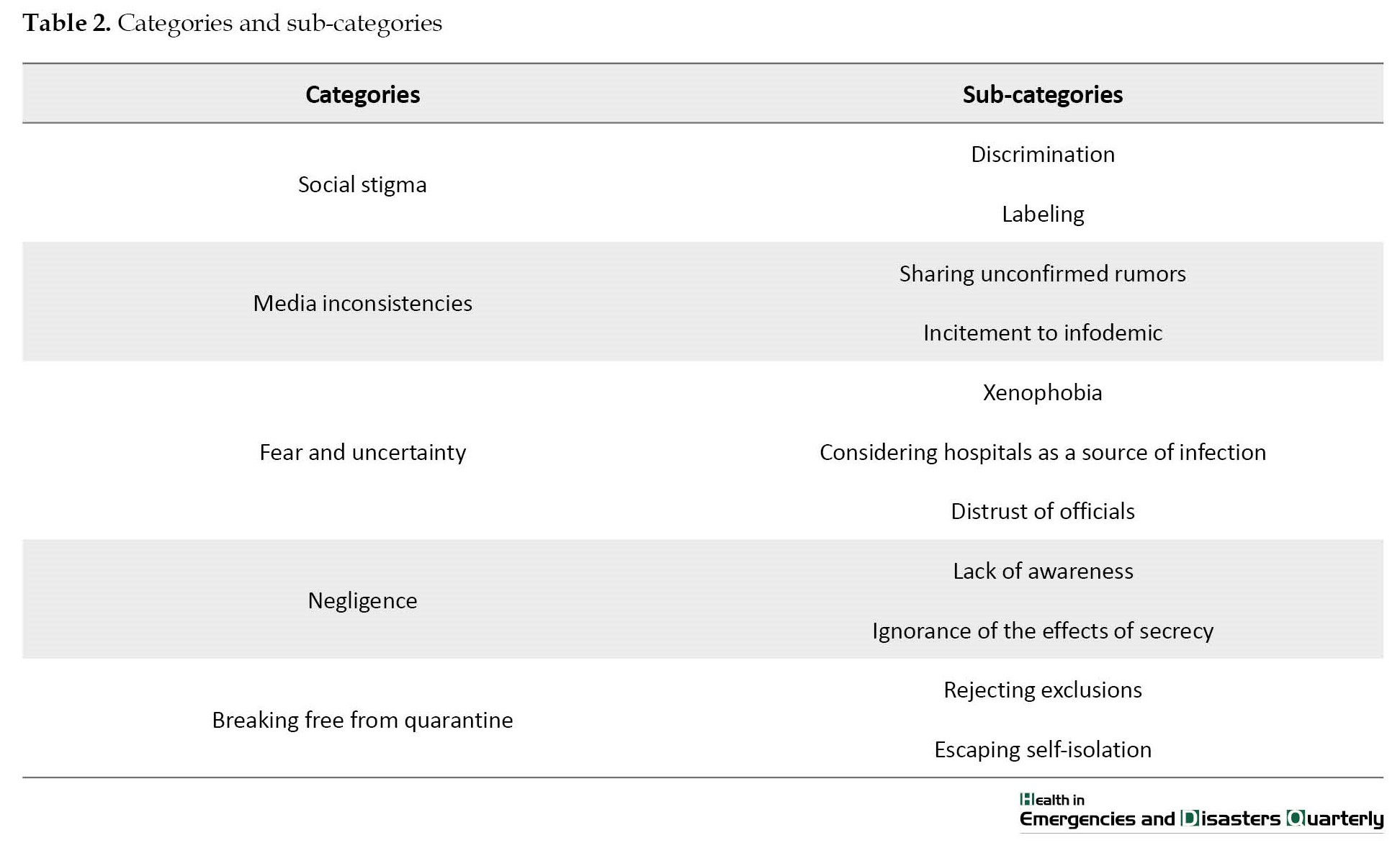

During the analysis of the interview data, 3201 codes were obtained, which later were classified into 5 main categories and 11 subcategories. The main categories included social stigma, media inconsistencies, fear and uncertainty, negligence, and breaking free from quarantine (Table 2).

Social stigma

Based on the experiences of the participants in this study, pandemics create social stigma and discriminatory behaviors toward all people who have been exposed to the virus. People use white lies to prevent being stigmatized. The use of white lies against stigma makes it more difficult to control the spread of the disease. This category had two subcategories discrimination and labeling.

Discrimination

The use of white lies to avoid confronting discriminatory behaviors in society prevents the immediate search for treatment and the use of health-promoting behaviors. In the case of patients with COVID-19, even the medical staff behaves discriminatingly in caring for affected patients or providing facilities to them. In this regard, the son of one of the patients with COVID-19 shared his experience as follows:

“In the emergency room, I told one of the hospital security staff that my mother had symptoms that I think is COVID-19. He quickly distanced himself from me and behaved in such a way that everyone distanced themselves from us. He did not even let me reach for a stretcher to take my mother to the hospital. Their behavior scared my mother a lot”.

Labeling

According to the participants’ experiences, being labeled as a victim is annoying. People who have a positive test or have recovered from the disease, in addition to healthcare workers who care for patients with COVID-19 are at risk of being labeled. Using white lies to prevent being labeled is a strategy that was used by the participants. One of the nurses in charge of caring for patients with COVID-19 in this regard stated the following sentence:

“You cannot even have a sneeze or cough, because people look at you as if you have COVID-19 disease”(Participant (P) 12).

Media inconsistencies

Media inconsistency according to the participants’ experiences was another reason for using white lies. People’s lectures in mass and virtual media about the use of traditional therapies, detox diets, and the effect of vitamin therapy in COVID-19 as well as intruding treatments for which no scientific research exists to prove its validity, are all white lies to reduce public stress. This category had two subcategories sharing unverified rumors and incitement to infodemic.

Sharing unconfirmed rumors

In many social networks, rumors are exchanged and sometimes the public follows them. The influence of media on the formation of public belief is undeniable. Overcoming false information that spreads through rumors in cyberspace is one of the challenges that must be addressed. A family member of a patient with COVID-19 in this regard stated the following sentence:

“Some people say that using hot water or hot air kills the virus. Some people say that children do not get the virus. It is not clear which one is right and which one is wrong” (P 9).

Incitement to infodemic

Research into the COVID-19 is still ongoing. However much of the misinformation reported in the media has not yet been proven and needs further investigation. This misinformation is repeated in public to reduce stress and anxiety. In this regard, one of the physicians participating in the study maintained the following sentence:

“We have patients who have been diagnosed with the disease, but we use the treatments that are being advertised on virtual networks and have no therapeutic effect. For example, we show people who followed that treatment and are now in good condition. Most people follow these baseless rumors” (P 4).

Fear and uncertainty

Fear and uncertainty are to be expected at the height of epidemics. This fear and uncertainty can motivate the use of white lies. According to the experiences of the participants, the category of fear and uncertainty had three subcategories, including fear of strangers or xenophobia, fear of medical centers and considering hospitals as a source of infection, and distrust of authorities/officials.

Xenophobia

Xenophobia is a subcategory that is derived from the participants’ experiences. Due to the spread of disease from Asia and its high prevalence among elderly people, fear and distrust of these groups make people avoid them. People use white lies to prevent society from avoiding elderlies. One of the patient’s companions who was taking care of him stated the following sentence:

“My son was a student in China. He returned to Iran when he became ill. It has been two months since he came back. None of the family members have been infected. But none of our relatives has been in contact with us. They are afraid of us” (P 23).

Considering hospitals as a source of infection

Medical centers and hospitals are a place to diagnose and treat diseases, such as COVID-19. In the case of people who have symptoms of the disease, they hide or make their symptoms look insignificant due to the fear of being hospitalized and entering the place where they are most exposed to the disease. These white lies that make the situation look good are based on fear and distrust of medical centers, and create relative peace of mind in people. In this regard, one of the patients with COVID-19 maintained the following sentence:

“I had a fever and cough last week. I wanted to come for a test, but everyone told me not to do so. They said even if you do not have a corona, you will be infected in the hospital” (P 41).

Distrust of officials

People’s distrust of the information received from the authorities leads to the pursuit of information from unofficial sources. According to the participants’ experiences, this distrust gives a chance to subjects who present health analyses that are not fundamentally based on truth and lead to the use of more expedient lies. In this regard, one of the infectious disease physicians added the following remark:

“The information that the government gives to people should be simplified to the extent that everyone can understand. The level of understanding of people is not the same and everyone has a different perception. Analyzing perceptions ultimately leads to ambiguity and mistrust”.(P 8).

Negligence

According to the participants’ experiences, negligence is one of the main reasons for using white lies in the pandemic period. People are tired of complying with health protocols and staying at home to escape the disease. Also, the lack of symptoms in many patients and constant changes in the symptoms of the disease are some of the issues that lead to public negligence. The category of negligence had two subcategories as follows:

Lack of awareness

Despite the efforts of all governmental and non-governmental organizations, the majority of people still do not have enough knowledge about the disease. This ignorance leads to the continuation of using white lies. In this regard, the sister of one of the patients with COVID-19 maintained the following remarks:

“When my sister got infected, we did not know what a corona was. Our neighbor who saw my sister said it was nothing. My sister was very scared. Our neighbor said it did not matter. It is a simple cold that comes and goes within a week. We later found out that this was not the case, and a large number of family members became infected and needed hospitalization” (P 32).

Ignoring the effects of secrecy

The participants’ experience stated that some people use white lies to conceal their illness because of the fear of rejection and social isolation as well as to maintain their reputation. However, ignoring the effects of secrecy comes at a high price, which is paid for by healthy people who are at risk of this disease. One of the nurses who had repeatedly witnessed the patients’ secrecy shared one of his experiences as follows:

“The patient had COVID-19. When asked in the emergency room, he said he had asthma and respiratory distress. I wear a mask and I am careful not to infect anyone” (P 20).

Breaking free from quarantine

In addition to people who do not have the COVID-19 disease, people who are carriers or people who have just recovered from the disease need quarantine. According to the participants’ experiences, many people try to avoid illness and quarantine by traveling to villages or out-of-town areas. This category had two subcategories as follows:

Rejecting exclusions

Quarantine imposes economic and psychological constraints on individuals. Many people do not accept these restrictions. People use white lies to get rid of these restrictions and to make the situation completely normal while continuing their normal affairs. In this regard, one of the nurses said the following sentence:

“When a family member gets infected, we warn the rest of the family to be in quarantine for a while. Most of them do not take it seriously. One goes to work and the other goes shopping. They try to deceive themselves and make things look good. They say my body is not infected and has no symptoms” (P 19).

Escaping self-isolation

During the pandemic, intercity traffic restrictions were imposed in many cities. Many people tried to get out of the city to stay away from the disease and believe that isolation is a good option to prevent infection. Many people also encourage their friends and family to follow them. In this regard, one of the patients shared his experience as follows:

“My friend said that there is a lot of illness in the city. He said that we could go to their villa for a while to escape the illness. He said this is the best way. My wife and I and a few of our mutual friends went to the villa together. One of our friends was ill and as a result 5 people became infected” (P 22).

Discussion

In this study, the experiences of patients with COVID-19 and people who were in close contact with COVID-19 patients concerning the use of white lies were examined. The stigma of disease and avoiding being labeled was found to be one of the reasons for using white lies in the study. Individuals in the community can prevent the spread of stigma associated with COVID-19 by knowing the facts and sharing them with others. Creating an environment in which information about the disease can be honestly and effectively shared is critical during a pandemic [11, 15].

The findings highlighted media inconsistencies as a prominent factor driving the use of white lies. Given the propensity for people to share rumors and misinformation through the media, it became crucial for media outlets to exercise self-censorship. It is recommended that they refrain from disseminating information that lacks a foundation in scientific evidence. Other research indicates that exposure to media-delivered information can induce significant fear in individuals. Therefore, a cautious and evidence-based approach by the media is essential to mitigate the unintentional spread of false information and its potential negative impact on public perceptions and emotions [16, 17, 18]. In a study by Cheung (2015), one of the methods identified for the dissemination of rumors and the subsequent instigation of fears was the use of training trainers [19]. In addressing this issue, the media can access current and precise information from the databases of reputable organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization (WHO). By focusing on the advancements in treatment, vaccine development, and successful prevention methods, the media can play a pivotal role in averting the spread of public fear. Additionally, sharing the experiences of individuals who have successfully recovered from COVID-19 contributes to public awareness of the facts and available treatment options. One of the categories we found in the present study in connection with the use of white lies was negligence with the subcategories of lack of awareness and ignoring the effects of secrecy. According to the findings of Person et al. (2004), when the general public needs to receive prompt information about a disease, there is a high risk of spreading false and untrue information [20]. Where information is unclear and open to interpretation, this can lead to people creating their own, and possibly ineffective, rules [21]. Creating a high level of awareness plays an important role in primary prevention and health promotion. In addition, it causes early detection of symptoms in the community [22].

According to the findings of this study, one of the main reasons for the use of white lies is breaking free from quarantine. Although the Iranian government initially did not accept quarantine, after the further spread of the disease, it restricted travel to big cities [23]. The study conducted by Webster et al. (2020) revealed a wide range of adherence to quarantine measures, spanning from 0% to 93% among individuals. The factors influencing people’s adherence to quarantine were identified as their understanding of the infectious disease outbreak and quarantine procedures, adherence to social norms, recognition of the benefits of quarantine, perceived risk of disease, and practical considerations of being in quarantine. In light of these findings, public health officials are urged to furnish the public with timely and clear protocols. Additionally, ensuring the availability of essential medical, food, and financial support for individuals during quarantine is imperative [24].

Conclusion

While individuals may resort to white lies to alleviate stress and prevent psychological harm, the inadvertent propagation of inaccurate information poses a risk to public health, potentially exacerbating the spread of the disease. During a pandemic, the dissemination of transparent and truthful information at the community level is crucial for fostering public understanding and acceptance of factual circumstances. It is advisable to rely on and reference scientific databases approved by organizations, such as the WHO, countering personal interpretations and rumors. Therefore, health authorities and the media play a pivotal role in providing reasoned and unambiguous information to curb the continued dissemination of white lies within the community during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study limitations:

The limited sample size and the qualitative nature of the study constrain the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, in line with the inherent nature of qualitative studies, the primary objective was not generalization. Despite these limitations, the outcomes of this study contribute valuable insights to the existing body of knowledge in this field.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was conducted under the oversight of the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, with the following assigned (Code: IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1397.568) Before participation, all individuals were provided with detailed information about the study’s objectives and methodology. Subsequently, they were requested to sign a written consent form. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their data, and the option of withdrawing from the study at any point was explicitly explained to them.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Mahboobeh Shali, approved by Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and was funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Alireza Nikbakht Nasrabadi, Zahra Abbasi Dolatabadi and Soodabeh Joolaee; Data collection: Touraj Harati Khalilabad; Data analyzing: Elham Navab and Maryam Esmaeili; Writing: Mahbobeh Shali; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants who generously contributed to this study. Additionally, appreciation is extended to the Tehran University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support to facilitate the completion of this project.

References

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) is the pandemic agent of COVID-19 disease that began in December 2019 in Wuhan, China [1, 2]. The intentional selection of the official name for the disease is aimed at preventing stigmatization. The term “co” represents corona, “vi” signifies virus, “d” denotes disease, and “19” denotes the year of the disease emergence (2019) [3].

In Iran, the initial case of COVID-19 was documented on February 19, 2019, in Qom City, Iran. Subsequently, the disease rapidly disseminated to neighboring provinces [2, 4]. Iran, being an Islamic country, adheres to principles that emphasize truthfulness, and individuals are encouraged to abstain from falsehoods, committing to honesty [5]. However, various emotional, professional, and cultural barriers may at times hinder the straightforward communication of accurate information by both healthcare providers and patients [5, 6, 7]. In such aforementioned situations, both healthcare providers and patients may find themselves resorting to the use of white lies as a means to manage the situation [8].

White lie, by definition, is an ethical decision without personal derive that is made in special circumstances, when people are faced with bitter truth, to protect one another against predictable harms [9]. To decide whether to present information or withhold the truth and use a white lie is an ethical challenge that requires knowledge of ethical principles [10, 11]. Alternatively, in complex situations, making an incorrect decision followed by inappropriate intervention could lead to adverse consequences for the patient, their family, or even the broader society. Engaging in dishonesty is not aligned with a person-centered approach. As such, preventing and managing this behavior necessitates interventions targeting its root causes. The utilization of white lies can be influenced by various factors, including cultural and social considerations [12]. Despite a search in the scientific literature, no study was found about the use of white lies in times of crisis. Nevertheless, there is a lack of comprehensive information regarding the specific circumstances that compel individuals to resort to white lies during a pandemic crisis. This study bridges this gap and investigates the experiences of patients with COVID-19, their families, and healthcare workers in employing white lies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative study was carried out from April to June 2020 in Tehran City, Iran. Purposeful sampling was used to select the participants from healthcare workers (physician and nurse) and patients with COVID-19 and their families in hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Willingness to participate in the study, having work experience in hospitals dealing with COVID-19 (for healthcare workers), having COVID-19 or caring for a patient with COVID-19 (for patient and their families), and being verbally capable of expressing personal experiences related to the study topic.

The data were collected using face-to-face individual and semi-structured interviews. Place of interviews were coordinated with the participants. An interview guide was used to ask questions about the participants’ experiences during the interview, including “have you ever experienced a situation during the COVID-19 pandemic?” “Where did you not want to or could not tell the truth to others?” “How did you use a white lie?” “Would you please explain more?”

Each interview lasted between 45 to 60 min. Data collection was continued until data saturation. Saturation in this research meant that no new code was extracted in the process of coding. Data analysis was conducted using the conventional content analysis approach, as proposed by Graneheim and Lundman [13]. Initially, the researchers listened to the interviews multiple times and subsequently transcribed them verbatim. The texts and accompanying field notes underwent a thorough review, with words, sentences, and paragraphs treated as conceptual units. They were then assigned specific codes. Data management was done using the MAXQDA software, version 12. The codes were compared in terms of similarities and differences and were classified. Trustworthiness was examined by the Guba and Lincoln criteria of credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability [14].

Credibility was enhanced through sustained engagement with the data throughout all phases, coupled with collaborative analysis. To conduct an external validation, preliminary findings were presented to a panel of experts at a seminar. Additionally, the participants in the study evaluated theme descriptions for a member check, further ensuring credibility, subsequently, and dependability.

To assess the transferability of the findings, we presented them to a diverse audience. Confirmability, requiring researcher neutrality, was maintained by documenting an audit trail, which elucidated the connection between the data, sources, and the derivation of conclusions and interpretations in this study.

Results

The participants consisted of 23 female and 27 male subjects with a mean age of 35±6.3 years. Also, 13 of the participants were patients with COVID-19 disease, 12 were family members of patients with COVID-19, and 25 were medical staff including physicians and nurses working in the treatment centers dedicated to COVID-19. All nurses had bachelor’s degrees and participating doctors had specialist degrees. Meanwhile, 6 people from the patient’s family had a bachelor’s degree, 3 people had a post-graduate degree, and 3 people had a secondary education. Also, 6 of the patients were illiterate, 3 had a bachelor’s degree, and 4 had a secondary education (Table 1).

During the analysis of the interview data, 3201 codes were obtained, which later were classified into 5 main categories and 11 subcategories. The main categories included social stigma, media inconsistencies, fear and uncertainty, negligence, and breaking free from quarantine (Table 2).

Social stigma

Based on the experiences of the participants in this study, pandemics create social stigma and discriminatory behaviors toward all people who have been exposed to the virus. People use white lies to prevent being stigmatized. The use of white lies against stigma makes it more difficult to control the spread of the disease. This category had two subcategories discrimination and labeling.

Discrimination

The use of white lies to avoid confronting discriminatory behaviors in society prevents the immediate search for treatment and the use of health-promoting behaviors. In the case of patients with COVID-19, even the medical staff behaves discriminatingly in caring for affected patients or providing facilities to them. In this regard, the son of one of the patients with COVID-19 shared his experience as follows:

“In the emergency room, I told one of the hospital security staff that my mother had symptoms that I think is COVID-19. He quickly distanced himself from me and behaved in such a way that everyone distanced themselves from us. He did not even let me reach for a stretcher to take my mother to the hospital. Their behavior scared my mother a lot”.

Labeling

According to the participants’ experiences, being labeled as a victim is annoying. People who have a positive test or have recovered from the disease, in addition to healthcare workers who care for patients with COVID-19 are at risk of being labeled. Using white lies to prevent being labeled is a strategy that was used by the participants. One of the nurses in charge of caring for patients with COVID-19 in this regard stated the following sentence:

“You cannot even have a sneeze or cough, because people look at you as if you have COVID-19 disease”(Participant (P) 12).

Media inconsistencies

Media inconsistency according to the participants’ experiences was another reason for using white lies. People’s lectures in mass and virtual media about the use of traditional therapies, detox diets, and the effect of vitamin therapy in COVID-19 as well as intruding treatments for which no scientific research exists to prove its validity, are all white lies to reduce public stress. This category had two subcategories sharing unverified rumors and incitement to infodemic.

Sharing unconfirmed rumors

In many social networks, rumors are exchanged and sometimes the public follows them. The influence of media on the formation of public belief is undeniable. Overcoming false information that spreads through rumors in cyberspace is one of the challenges that must be addressed. A family member of a patient with COVID-19 in this regard stated the following sentence:

“Some people say that using hot water or hot air kills the virus. Some people say that children do not get the virus. It is not clear which one is right and which one is wrong” (P 9).

Incitement to infodemic

Research into the COVID-19 is still ongoing. However much of the misinformation reported in the media has not yet been proven and needs further investigation. This misinformation is repeated in public to reduce stress and anxiety. In this regard, one of the physicians participating in the study maintained the following sentence:

“We have patients who have been diagnosed with the disease, but we use the treatments that are being advertised on virtual networks and have no therapeutic effect. For example, we show people who followed that treatment and are now in good condition. Most people follow these baseless rumors” (P 4).

Fear and uncertainty

Fear and uncertainty are to be expected at the height of epidemics. This fear and uncertainty can motivate the use of white lies. According to the experiences of the participants, the category of fear and uncertainty had three subcategories, including fear of strangers or xenophobia, fear of medical centers and considering hospitals as a source of infection, and distrust of authorities/officials.

Xenophobia

Xenophobia is a subcategory that is derived from the participants’ experiences. Due to the spread of disease from Asia and its high prevalence among elderly people, fear and distrust of these groups make people avoid them. People use white lies to prevent society from avoiding elderlies. One of the patient’s companions who was taking care of him stated the following sentence:

“My son was a student in China. He returned to Iran when he became ill. It has been two months since he came back. None of the family members have been infected. But none of our relatives has been in contact with us. They are afraid of us” (P 23).

Considering hospitals as a source of infection

Medical centers and hospitals are a place to diagnose and treat diseases, such as COVID-19. In the case of people who have symptoms of the disease, they hide or make their symptoms look insignificant due to the fear of being hospitalized and entering the place where they are most exposed to the disease. These white lies that make the situation look good are based on fear and distrust of medical centers, and create relative peace of mind in people. In this regard, one of the patients with COVID-19 maintained the following sentence:

“I had a fever and cough last week. I wanted to come for a test, but everyone told me not to do so. They said even if you do not have a corona, you will be infected in the hospital” (P 41).

Distrust of officials

People’s distrust of the information received from the authorities leads to the pursuit of information from unofficial sources. According to the participants’ experiences, this distrust gives a chance to subjects who present health analyses that are not fundamentally based on truth and lead to the use of more expedient lies. In this regard, one of the infectious disease physicians added the following remark:

“The information that the government gives to people should be simplified to the extent that everyone can understand. The level of understanding of people is not the same and everyone has a different perception. Analyzing perceptions ultimately leads to ambiguity and mistrust”.(P 8).

Negligence

According to the participants’ experiences, negligence is one of the main reasons for using white lies in the pandemic period. People are tired of complying with health protocols and staying at home to escape the disease. Also, the lack of symptoms in many patients and constant changes in the symptoms of the disease are some of the issues that lead to public negligence. The category of negligence had two subcategories as follows:

Lack of awareness

Despite the efforts of all governmental and non-governmental organizations, the majority of people still do not have enough knowledge about the disease. This ignorance leads to the continuation of using white lies. In this regard, the sister of one of the patients with COVID-19 maintained the following remarks:

“When my sister got infected, we did not know what a corona was. Our neighbor who saw my sister said it was nothing. My sister was very scared. Our neighbor said it did not matter. It is a simple cold that comes and goes within a week. We later found out that this was not the case, and a large number of family members became infected and needed hospitalization” (P 32).

Ignoring the effects of secrecy

The participants’ experience stated that some people use white lies to conceal their illness because of the fear of rejection and social isolation as well as to maintain their reputation. However, ignoring the effects of secrecy comes at a high price, which is paid for by healthy people who are at risk of this disease. One of the nurses who had repeatedly witnessed the patients’ secrecy shared one of his experiences as follows:

“The patient had COVID-19. When asked in the emergency room, he said he had asthma and respiratory distress. I wear a mask and I am careful not to infect anyone” (P 20).

Breaking free from quarantine

In addition to people who do not have the COVID-19 disease, people who are carriers or people who have just recovered from the disease need quarantine. According to the participants’ experiences, many people try to avoid illness and quarantine by traveling to villages or out-of-town areas. This category had two subcategories as follows:

Rejecting exclusions

Quarantine imposes economic and psychological constraints on individuals. Many people do not accept these restrictions. People use white lies to get rid of these restrictions and to make the situation completely normal while continuing their normal affairs. In this regard, one of the nurses said the following sentence:

“When a family member gets infected, we warn the rest of the family to be in quarantine for a while. Most of them do not take it seriously. One goes to work and the other goes shopping. They try to deceive themselves and make things look good. They say my body is not infected and has no symptoms” (P 19).

Escaping self-isolation

During the pandemic, intercity traffic restrictions were imposed in many cities. Many people tried to get out of the city to stay away from the disease and believe that isolation is a good option to prevent infection. Many people also encourage their friends and family to follow them. In this regard, one of the patients shared his experience as follows:

“My friend said that there is a lot of illness in the city. He said that we could go to their villa for a while to escape the illness. He said this is the best way. My wife and I and a few of our mutual friends went to the villa together. One of our friends was ill and as a result 5 people became infected” (P 22).

Discussion

In this study, the experiences of patients with COVID-19 and people who were in close contact with COVID-19 patients concerning the use of white lies were examined. The stigma of disease and avoiding being labeled was found to be one of the reasons for using white lies in the study. Individuals in the community can prevent the spread of stigma associated with COVID-19 by knowing the facts and sharing them with others. Creating an environment in which information about the disease can be honestly and effectively shared is critical during a pandemic [11, 15].

The findings highlighted media inconsistencies as a prominent factor driving the use of white lies. Given the propensity for people to share rumors and misinformation through the media, it became crucial for media outlets to exercise self-censorship. It is recommended that they refrain from disseminating information that lacks a foundation in scientific evidence. Other research indicates that exposure to media-delivered information can induce significant fear in individuals. Therefore, a cautious and evidence-based approach by the media is essential to mitigate the unintentional spread of false information and its potential negative impact on public perceptions and emotions [16, 17, 18]. In a study by Cheung (2015), one of the methods identified for the dissemination of rumors and the subsequent instigation of fears was the use of training trainers [19]. In addressing this issue, the media can access current and precise information from the databases of reputable organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization (WHO). By focusing on the advancements in treatment, vaccine development, and successful prevention methods, the media can play a pivotal role in averting the spread of public fear. Additionally, sharing the experiences of individuals who have successfully recovered from COVID-19 contributes to public awareness of the facts and available treatment options. One of the categories we found in the present study in connection with the use of white lies was negligence with the subcategories of lack of awareness and ignoring the effects of secrecy. According to the findings of Person et al. (2004), when the general public needs to receive prompt information about a disease, there is a high risk of spreading false and untrue information [20]. Where information is unclear and open to interpretation, this can lead to people creating their own, and possibly ineffective, rules [21]. Creating a high level of awareness plays an important role in primary prevention and health promotion. In addition, it causes early detection of symptoms in the community [22].

According to the findings of this study, one of the main reasons for the use of white lies is breaking free from quarantine. Although the Iranian government initially did not accept quarantine, after the further spread of the disease, it restricted travel to big cities [23]. The study conducted by Webster et al. (2020) revealed a wide range of adherence to quarantine measures, spanning from 0% to 93% among individuals. The factors influencing people’s adherence to quarantine were identified as their understanding of the infectious disease outbreak and quarantine procedures, adherence to social norms, recognition of the benefits of quarantine, perceived risk of disease, and practical considerations of being in quarantine. In light of these findings, public health officials are urged to furnish the public with timely and clear protocols. Additionally, ensuring the availability of essential medical, food, and financial support for individuals during quarantine is imperative [24].

Conclusion

While individuals may resort to white lies to alleviate stress and prevent psychological harm, the inadvertent propagation of inaccurate information poses a risk to public health, potentially exacerbating the spread of the disease. During a pandemic, the dissemination of transparent and truthful information at the community level is crucial for fostering public understanding and acceptance of factual circumstances. It is advisable to rely on and reference scientific databases approved by organizations, such as the WHO, countering personal interpretations and rumors. Therefore, health authorities and the media play a pivotal role in providing reasoned and unambiguous information to curb the continued dissemination of white lies within the community during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study limitations:

The limited sample size and the qualitative nature of the study constrain the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, in line with the inherent nature of qualitative studies, the primary objective was not generalization. Despite these limitations, the outcomes of this study contribute valuable insights to the existing body of knowledge in this field.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was conducted under the oversight of the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, with the following assigned (Code: IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1397.568) Before participation, all individuals were provided with detailed information about the study’s objectives and methodology. Subsequently, they were requested to sign a written consent form. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their data, and the option of withdrawing from the study at any point was explicitly explained to them.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Mahboobeh Shali, approved by Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and was funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Alireza Nikbakht Nasrabadi, Zahra Abbasi Dolatabadi and Soodabeh Joolaee; Data collection: Touraj Harati Khalilabad; Data analyzing: Elham Navab and Maryam Esmaeili; Writing: Mahbobeh Shali; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants who generously contributed to this study. Additionally, appreciation is extended to the Tehran University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support to facilitate the completion of this project.

References

- Yang W, Cao Q, Qin L, Wang X, Cheng Z, Pan A, et al. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19):A multicenter study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. The Journal of Infection. 2020; 80(4):388-93. [DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.016] [PMID]

- Dolatabadi ZA, Shali M, Foodani MN, Delkhosh M, Shahmari M, Nikbakhtnasrabadi A. Experiences and lessons learned by clinical nurse managers during covid-19 pandemic in Iran. Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Sciences. 2023; 10(2):e138161. [Link]

- Foodani MN, Abdulhusein M, Imanipour M, Bahrampouri S, Dolatabadi ZA. Relationship between professional quality of life and covid-19 anxiety among nurses of emergency and intensive care units in Najaf, Iraq. Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Sciences. 2023; 10(2):e135972. [Link]

- Nash M. EBOOK: Physical health and well-being in mental health nursing: Clinical skills for practice. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014. [Link]

- Chamsi-Pasha H, Albar MA. Ethical dilemmas at the end of life: Islamic perspective. Journal of Religion and Health. 2017; 56(2):400-10. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-016-0181-3] [PMID]

- Zamani A, Shahsanai A, Kivan S, Hematti S. [Iranian physicians and patients attitude toward truth telling of cancer (Persian)]. Journal of Isfahan Medical School. 2011; 29(143):752-60. [Link]

- Miresmaeeli SS, Esmaeili N, Sadeghi Ashlaghi S, Abbasi Dolatabadi Z. Disaster risk assessment among Iranian exceptional schools. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2022; 16(2):678-82. [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2020.425] [PMID]

- Hasselkus BR. Everyday ethics in dementia day care: Narratives of crossing the line. The Gerontologist. 1997; 37(5):640-9. [DOI:10.1093/geront/37.5.640] [PMID]

- Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Joolaee S, Navvab E, Esmaeilie M, Shali M. [A concept analysis of white lie from nurses’ perspectives: A hybrid model (Persian)]. Journal of Hayat. 2019; 25(3):309-24. [Link]

- Hekmat Afshar M, Jooybari L, Sanagou A, Kalantari S. [Study of factors affecting moral distress among nurses: A review of previous studies (Persian)]. Education and Ethics In Nursing. 2013; 1(1):22-8. [Link]

- Seyedin H, Moradimajd P, Bagheri H, Abbasi Dolatabadi Z, Nasiri A. [Providing a chemical events and Threatâ s preparedness model for hospitals in the country: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Journal of Military Medicine. 2022; 23(3):220-7. [DOI:10.30491/JMM.23.3.220]

- James IA, Wood-Mitchell AJ, Waterworth AM, Mackenzie LE, Cunningham J. Lying to people with dementia: Developing ethical guidelines for care settings. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006; 21(8):800-1. [DOI:10.1002/gps.1551] [PMID]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15(9):1277-88. [DOI:10.1177/1049732305276687] [PMID]

- Kakaei S, Zakerimoghadam M, Rahmanian M, Dolatabadi ZA. The impact of climate change on heart failure: A narrative review study. Shiraz E-Medical Journal. 2021; 22(9):e107895 [DOI:10.5812/semj.107895]

- Garfin DR, Silver RC, Holman EA. The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychology. 2020; 39(5):355-7. [DOI:10.1037/hea0000875] [PMID]

- Mertens G, Gerritsen L, Duijndam S, Salemink E, Engelhard IM. Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020; 74:102258. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102258]

- Navab E, Negarandeh R, Peyrovi H, Navab P. Stigma among Iranian family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A hermeneutic study. Nursing and Health Sciences. 2013; 15(2):201-6. [DOI:10.1111/nhs.12017] [PMID]

- Cheung EL. An outbreak of fear, rumours and stigma: Psychosocial support for the Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in West Africa. Intervention. 2015; 13(1):45 - 76. [DOI:10.1097/WTF.0000000000000079]

- Person B, Sy F, Holton K, Govert B, Liang A; National Center for Inectious Diseases/SARS Community Outreach Team. Fear and stigma: The epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004; 10(2):358-63. [DOI:10.3201/eid1002.030750] [PMID]

- Braunack-Mayer A, Tooher R, Collins JE, Street JM, Marshall H. Understanding the school community’s response to school closures during the H1N1 2009 influenza pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13:344. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-13-344] [PMID]

- Ahmed EF, Shehata MAA, Elheeny AAH. COVID-19 awareness among a group of Egyptians and their perception toward the role of dentists in its prevention: A pilot cross-sectional survey Journal of Public Health. 2022; 30(2):435-40. [DOI:10.1007/s10389-020-01318-8] [PMID]

- Abdi M, Mirzaei R. Iran without mandatory quarantine and with social distancing strategy against coronavirus disease (covid-19). Health Security. 2020; 18(3):257-9. [DOI:10.1089/hs.2020.0041] [PMID]

- Webster RK, Brooks SK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Rubin GJ. How to improve adherence with quarantine: Rapid review of the evidence. Public Health. 2020; 182:163-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.007] [PMID]

Type of article: Research |

Subject:

Qualitative

Received: 2023/06/6 | Accepted: 2023/11/8 | Published: 2024/01/1

Received: 2023/06/6 | Accepted: 2023/11/8 | Published: 2024/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |