Volume 10, Issue 2 (Winter 2025)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025, 10(2): 131-142 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yarmohammadian M H, Akbari F, Niaraees Zavare A S, Rezaei F. Community-based Disaster Preparedness; A Training Program Based on Needs Assessment. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025; 10 (2) :131-142

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-597-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-597-en.html

1- Department of Health in Disasters and Emergencies, Health and Economics Research Center (HMERC), School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Isfahan, Iran.

2- Health Management and Economics Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Health Economics, School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Health in Disasters and Emergencies, Social Determinants of Health (SDH) Research Center, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Isfahan, Iran. ,f.rezaei.pro@gmail.com

2- Health Management and Economics Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Health Economics, School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Health in Disasters and Emergencies, Social Determinants of Health (SDH) Research Center, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Isfahan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 525 kb]

(972 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3828 Views)

Full-Text: (1053 Views)

Introduction

Community-based health organizations (CBHOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have a gatekeeping role where public participation can be achieved to promote community-based preparedness measures [1]. In developed countries, community-based organizations (CBOs) and faith-based organizations (FBOs) are the main partners of health systems as they are well-equipped with community knowledge, structure, and resources. They have received the necessary training in risk communication and building social trust in public organizations during disasters [2-4]. According to the Sendai framework, all countries should reduce the risk of disasters by 2030 and promote local cooperation and risk communications through CBOs and NGOs along with the use of knowledge, innovation, and education based on the Hyogo framework [5, 6]. Therefore, the training of NGOs/CBOs plays a vital role in providing early support and health services, disseminating important information, providing logistics services, and facilitating opportunities to discuss policies and operational plans in emergencies [7-9]. The CBOs/NGOs can help emergency management organizations access and manage social networks and voluntary resources [10]. Accordingly, specialized CBOs/NGOs can provide well-qualified health care and rehabilitation services to vulnerable groups when governments suffer from limited resources after disasters [11, 12].

To address the educational needs of a community, Takahashi et al. [13] and Prasetyo et al. [14] suggested that setting up of a school health is the most applicable strategy due to the inefficiency of practical training that only relies on successful interactive, inquiry-based, and experiential learning data. The continuous education of disaster risk reduction teachers is another challenge. Therefore, due to the gaps in disaster health risk literacy, Kagawa et al. [15] and Chan et al. [16] showed that it is necessary to develop a more systematized, reinforced, and sustainable educational program. Among the five main factors needed for the success of community participation identified by Enshassi et al. [17], the factors of risk perception, education and knowledge, and awareness of disaster management are directly influenced by community education. Hajito et al. [18] emphasized that communities with proper training and education have a higher ability to cope with disasters. In the same way, training provides a golden opportunity to develop the capabilities of CBOs/NGOs and their registered volunteers [19, 20] which led to less sensitiveness and responsibility of CBOs.

Community education is a cornerstone for fostering community partnerships and enhancing disaster management abilities. Also, education can improve the proficiency of CBOs/NGOs and their volunteers, equipping them with the tools to find and effectively mitigate the challenges posed by disasters. In this regard, in this qualitative study, we tried to develop a well-structured education program and answer the question, “What are the main concepts that CBHOs/NGOs in Iran should know before participating in managing disasters and emergency situations?”

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This qualitative study was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 25 key informants from 135 registered CBHOs and NGOs in Isfahan, Iran, with previous experience of cooperation with the health system in natural disasters who were experts in the field of social services. They were selected using purposive and snowball sampling methods. Snowball sampling was employed to identify the hard-to-reach key informants, as some of them were not registered workers in any organization (e.g. female volunteers) or had retired from their jobs. Moreover, 13 documents and instructions provided by the Iranian government to guide the participation of the non-government sector were also reviewed by two independent interviewers. In case of a dispute between them, the third researcher made the final decision. The content analysis method was used to identify the basic educational needs of CBHOs/NGOs before participating in disaster management. In the second phase, three focus group discussion (FGD) meetings were held to enrich and refine the main concepts identified in the first phase using a checklist. The key informants in FDG meetings were directors or members of the board of trustees of CBHOs, NGOs, or professors in disaster health and medical education.

Data collection and management

An interview guide was developed by the authors before conducting the interviews which included supporting items related to the goals, objectives, and syllabuses of an educational program for the organizations. The interview protocol was first tested as a pilot with the participation of five key informants who were not from among the participants. Finally, the interviews were conducted. Each interview lasted 30 minutes to an hour and was conducted in a location determined by the interviewees. All interviewees signed an informed consent form before recording their voices. We also obtained permission from the head of the institution and state government. The interview continued until reaching data saturation. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. After reaching the main categories, they were provided to interviewees to comment on the emerging concepts. The transcripts were entered into MAXQDA software, version 2018. Weekly sessions were held to analyze the transcriptions. The semantic units were coded and categorized. Throughout the coding process, the coders compared the codes and discussed disagreements. Finally, they came to an agreement on the final codes (a 97.6% agreement). Credibility was achieved after reviewing the literature and participating in CBHOs/NGOs coalition meetings.

In the second phase, the thematic content analysis led to a curriculum design that translates categories of educational needs into goals and objectives of the curriculum. Other components of the curriculum, such as syllabus, duration, budgeting, teaching methods/strategies, duration, and target groups were designed according to the curriculum development process. In this phase, the research team considered all the misconceptions and made reasonable changes in the main concepts until reaching the cohesion of goals, syllabuses, teaching strategies/methods, and evaluation tools. The experts had enough time (two weeks) to provide any suggestions in a WhatsApp group and discuss more details to reach a mutual agreement. Adjusting teaching methods/strategies based on the syllabuses and related goals was the most challenging part. In this regard, the research team elicited the opinions of participating experts and other experts in the field of education. The designed curriculum was finally reviewed and validated by experts.

Results

Participants included 17 members of the CBHOs’ board of trustees and 8 community plan liaison officers of NGOs. They were in the age range of 45-81 years. The majority of them were male (n=17, 5%) and had master’s degrees in nursing or were undergraduates and graduates, with 4-35 years of experience in the CBHOs.

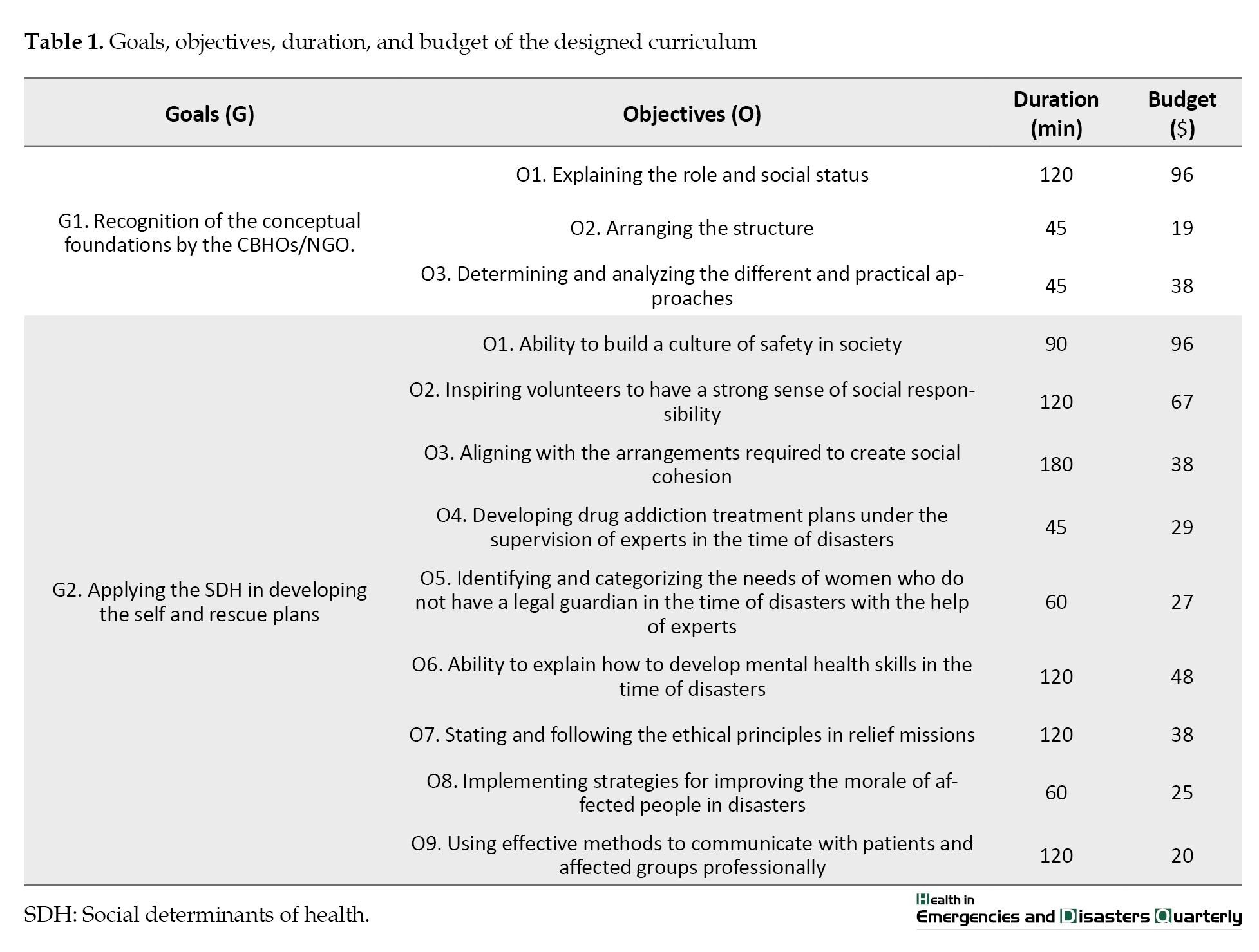

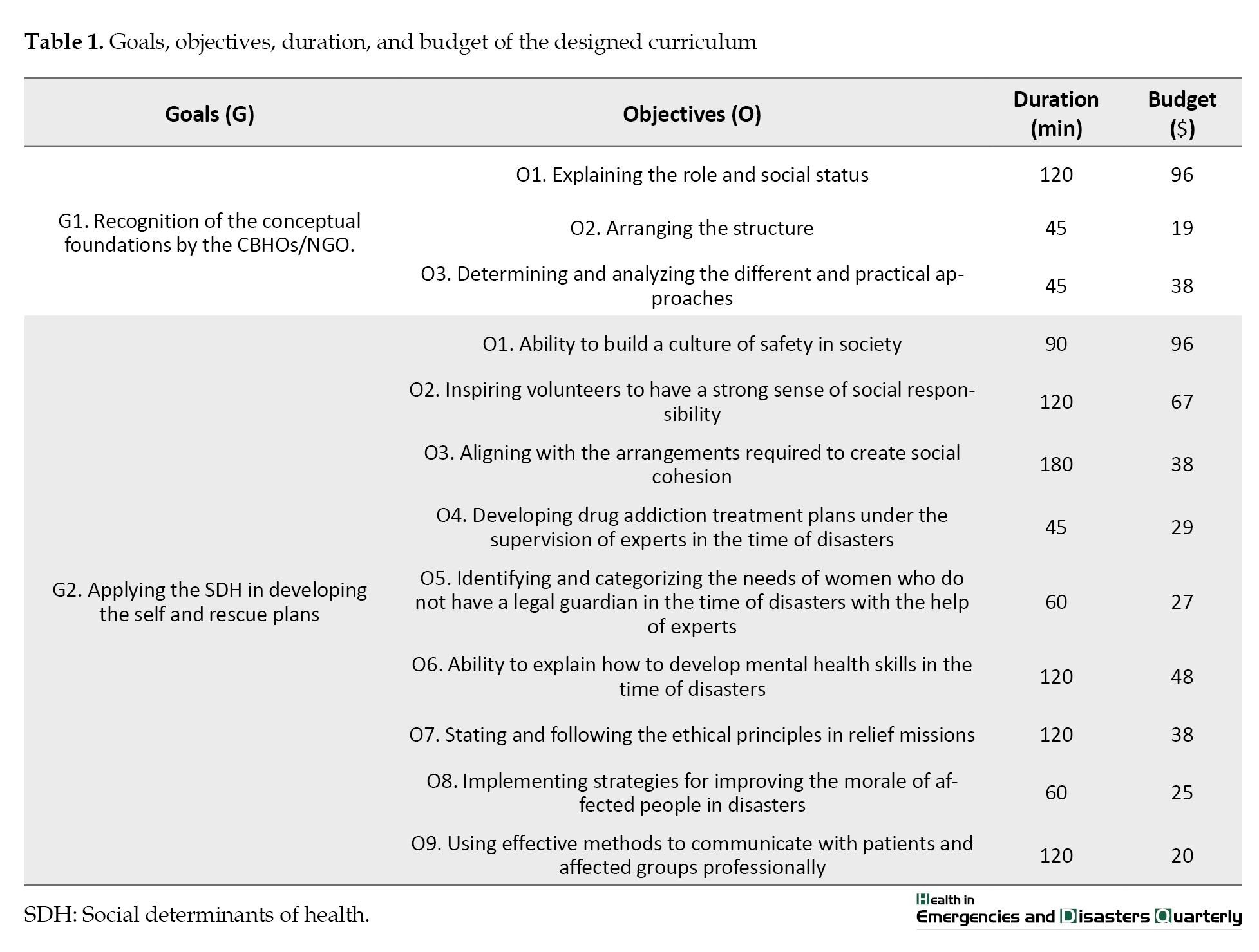

In the first phase, the extracted main theme was “The theoretical concept, social role, official position, and structure of CBHOs/NGOs in disasters”. Two categories (goals) and 12 sub-categories (objectives) were extracted after analysis (Table 1).

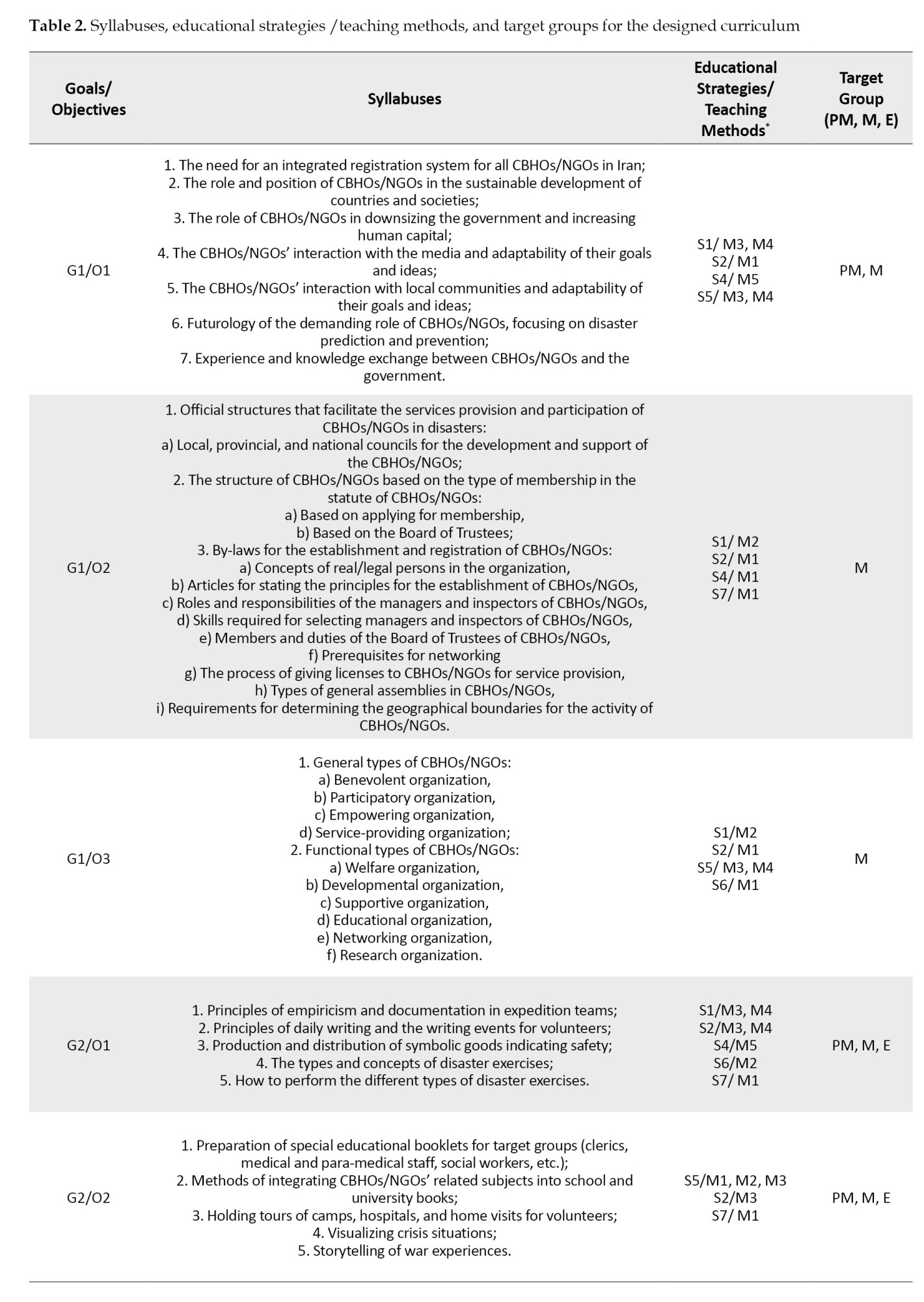

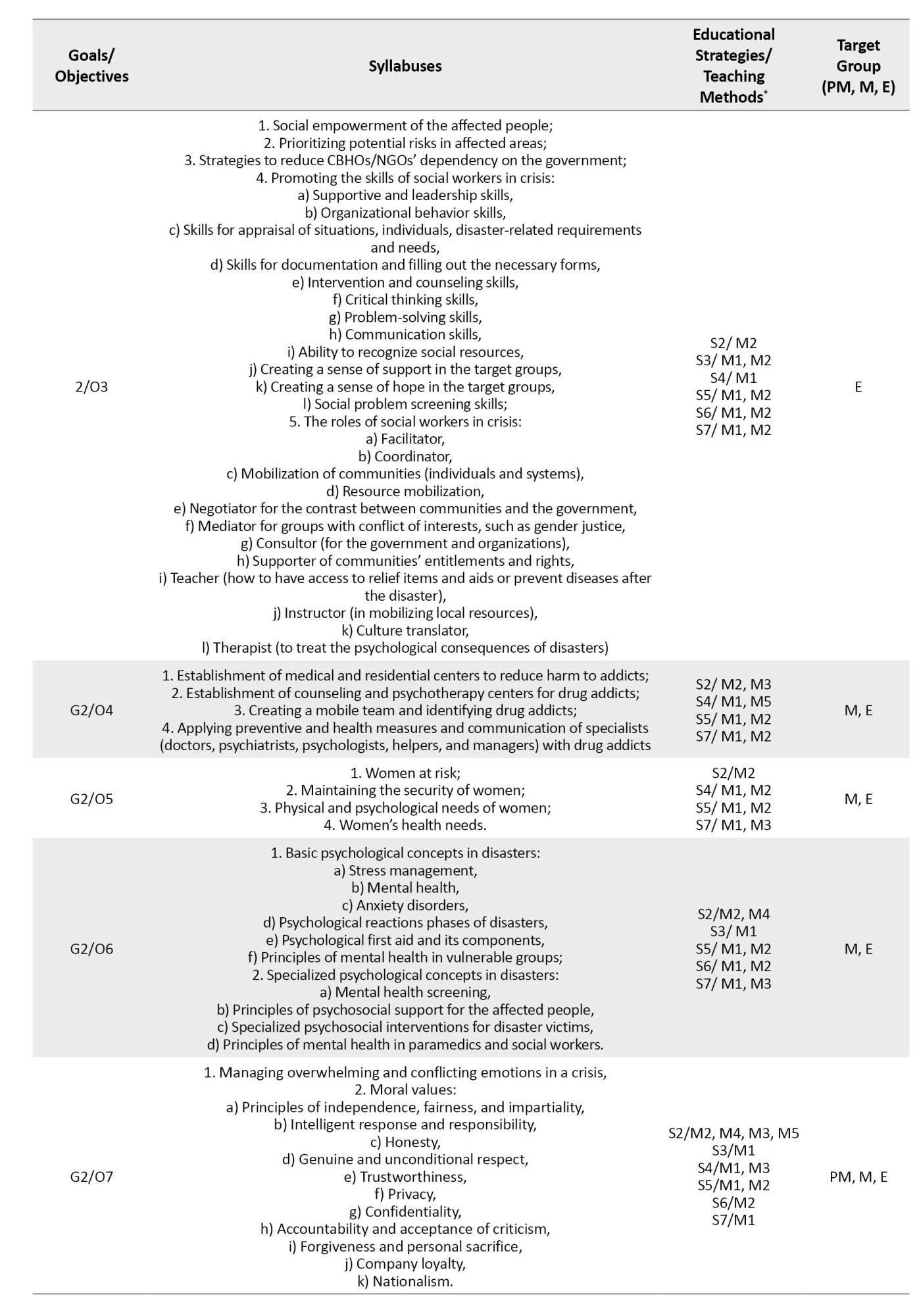

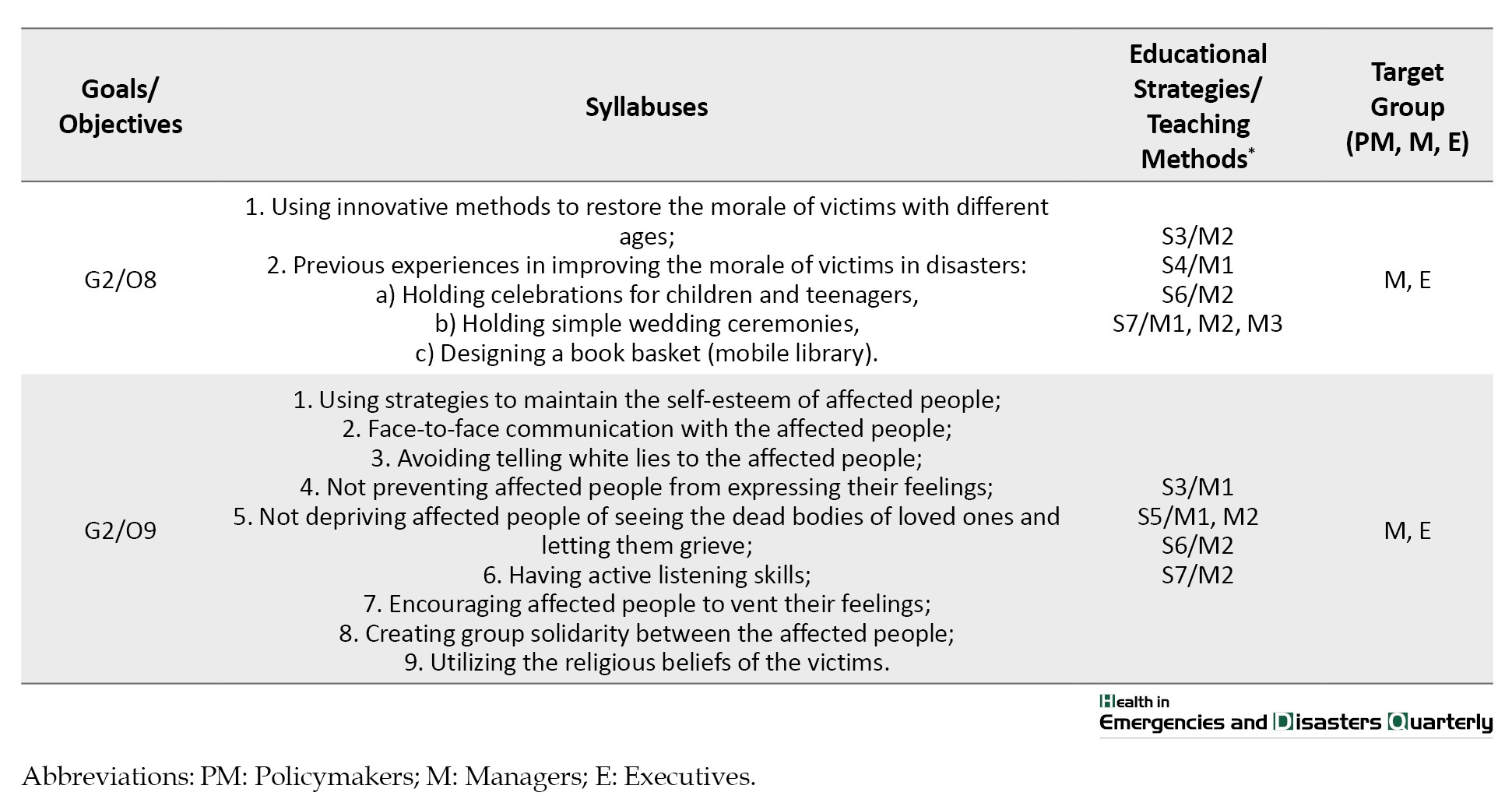

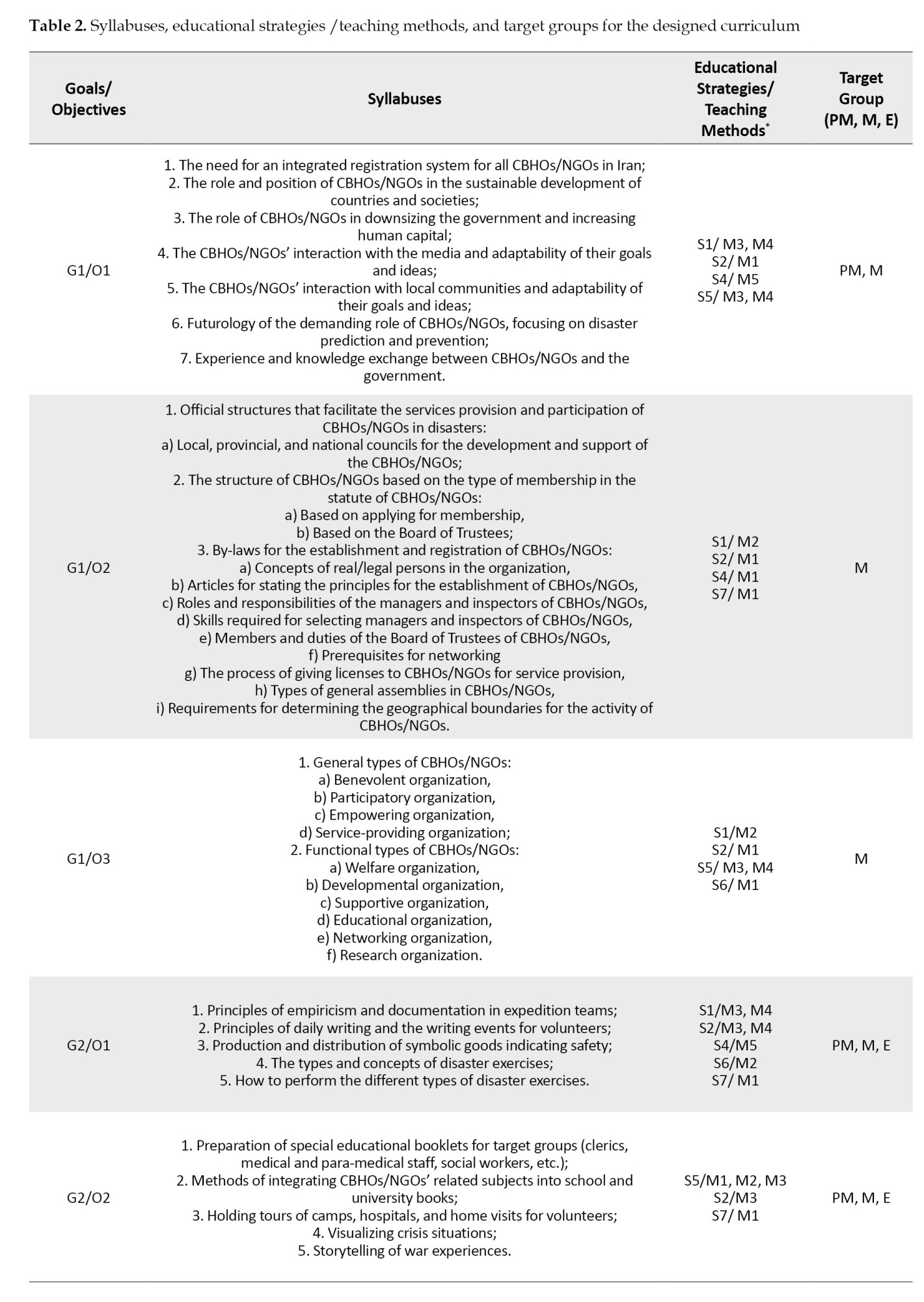

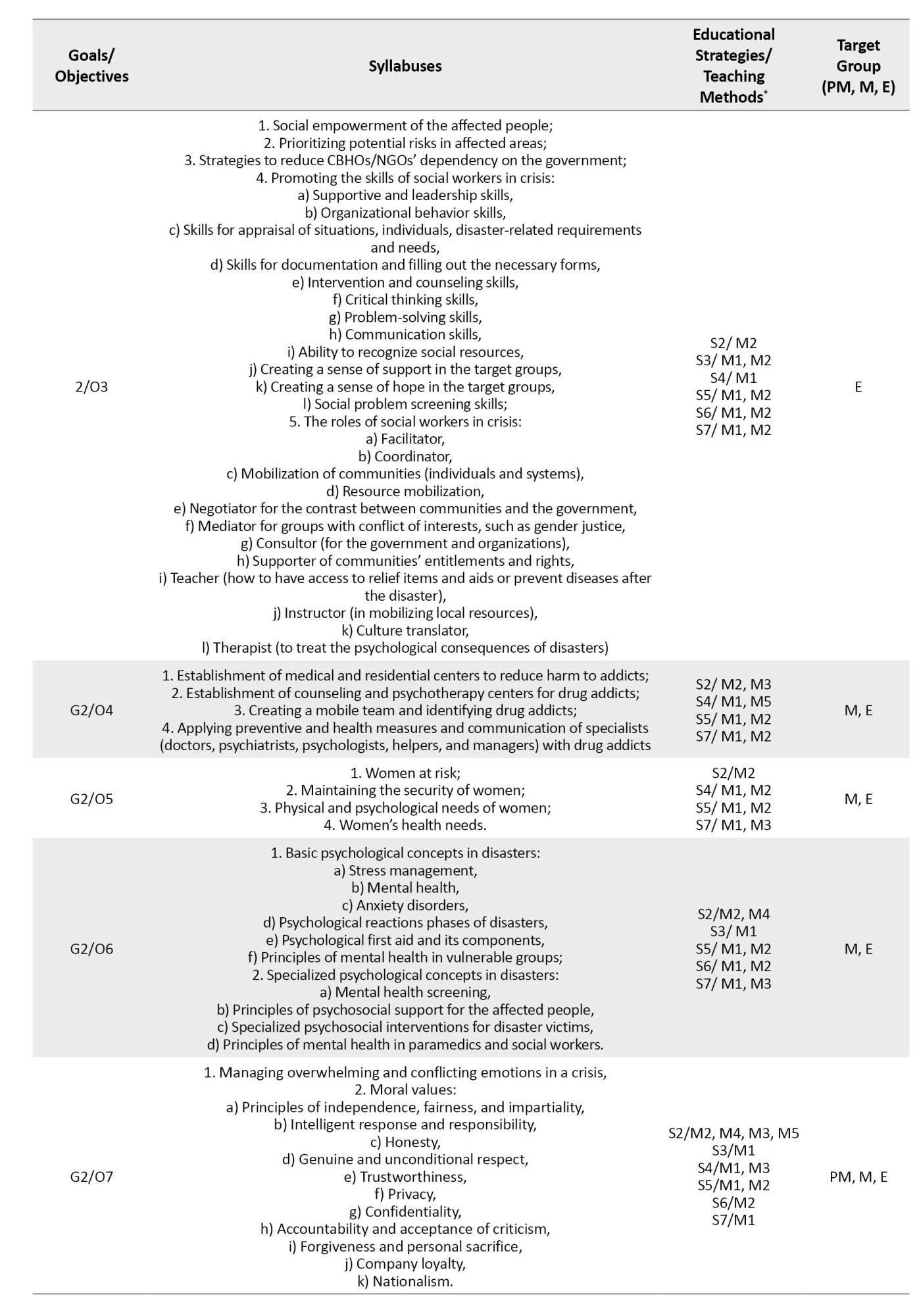

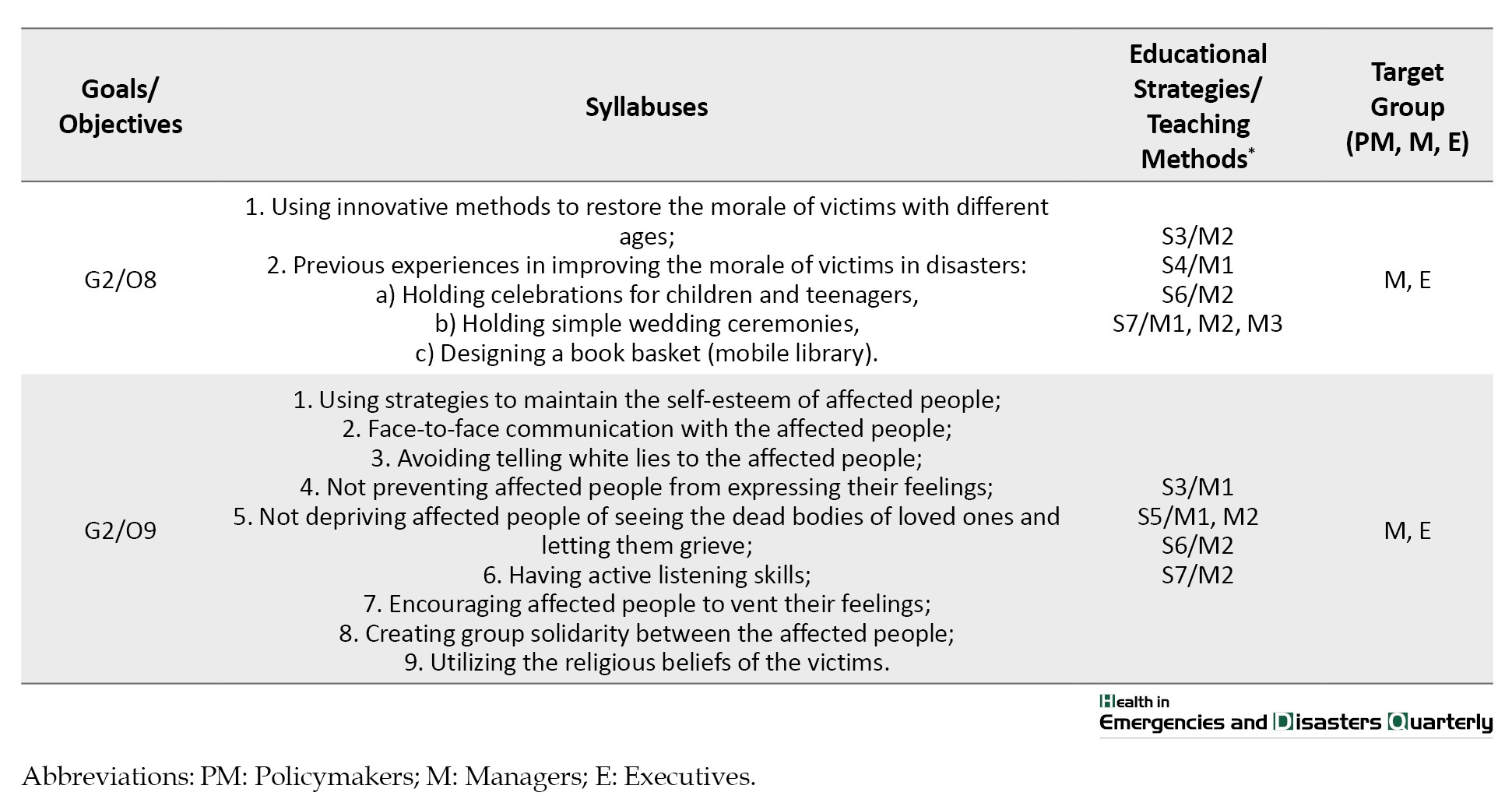

The first goal was to recognize the conceptual foundations of the CBHOs and NGOs before participation in disaster management through three corresponding objectives. The second goal was to consider the social determinants of health (SDH) to help organizations have safe and secure plans based on nine objectives. Each objective was defined based on budget, time, educational strategies/teaching methods, and target groups (Table 2).

Discussion

The role and social status of HCBOs/NGOs participating in disaster management have been growing, which has made it difficult for the governments to manage. They have emerged as exigent sectors for disaster management. These organizations enhance communication and accelerate collective actions to improve community resilience and social/environmental goals [21]. Therefore, based on the first subcategory (objective) of the first category (goal) identified in this study, educational courses should make HCBOs/NGOs aware of their social impacts on affected communities after disasters. They should not act beyond the pre-defined roles and tasks in which they have no expertise to avoid adverse effects. Moreover, the structures of HCBOs/NGOs vary in hierarchies from a relatively strong central authority to a more loos local arrangement. Alternatively, they may be based in a single country and operate transnationally. Based on the second subcategory (objective), with the improvement in structure, more HCBOs/NGOs can become active at the national or even the global level [22]. Therefore, the educational program in this study for these organizations is not just to hold some classes without any theoretical and conceptual framework that can influence their work. Without a framework, it becomes difficult for field workers to effectively transfer knowledge and share experiential learning in any location, status, background, or expertise. The classification of participatory approaches for disaster management (the third objective) has also been recommended by the United Nations agencies [23]. The HCBOs/NGOs are well-recognized providers of social, educational and health services in partnership with private and public actors. We recommend these practice-based goals and objectives for CBHOs/NGOs to be more knowledgeable of their roles.

Based on the second category (goal) identified in this study with nine subcategories (objectives), which was the consideration of SDH in education, the first objective was to build a culture of safety in society, which refers to the product of values and attitudes in employees, managers, customers, and community members that determine the safety in dangerous situations, and all organizations should have a stake in it. In the response phase of disaster management, each individual and each organization should be aware of the unknown risks and dangers caused by various activities [24]. Education in safety culture can satisfy individuals and organizations and reduce casualties in the event of a disaster [25, 26]. Educational courses should aim to create spontaneous behaviors in volunteer groups and organizations and enhance safety to adapt to disasters. Inspiring volunteers to have a strong sense of social responsibility was the second objective, which is a key principle in reducing disaster risk and creating resilience. One way to improve the capacity and accountability of the health system in disasters in line with the second priority of the Sendai framework regarding disaster risk governance is to increase the quantity and quality of volunteers by using clients and students as organizations’ volunteers [27, 28]. In developed countries, disaster management relies highly on professionals. Given the increased risk of disasters worldwide [29], it is likely that volunteers can increase the capacity needed to respond to emergencies and disasters in the future. If communities want to maintain or increase their resilience to disasters and thus reduce their vulnerability, the motivational and social resources that lead to citizens’ participation in disasters should be defined well. To strengthen voluntary participation in disasters, the importance of motivation factor for volunteerism should be taught in educational courses to create the right conditions for further participation.

Social cohesion is an important factor in the welfare of society, especially in the time of disasters. Based on the third objective, the emergent social cohesion managed by social media can play an important role in improving communities’ ability to cope with disasters. Fan et al. also showed that during Hurricane Harvey, a good history of social cohesion in affected regions influenced communication and physical closeness [30]. Chowdhury showed that access to local loans provided by a CBO positively affected social cohesion during the recovery phase [31]. Samarakoon and Abeykoon showed that social cohesion can emerge as a latent function of a disaster and play an essential role in the victims’ recovery. According to them, receiving help from non-victims for more than three months may reduce psychosocial tension in victims [32]. Social cohesion in times of disasters is transparent in our country. However, donations are mostly sent in the first month. This somehow creates community dependency, but the sudden decline in donations has devastating effects on the community. Therefore, the volunteer groups need to be trained in this field.

In line with the fourth objective (drug addiction treatment planning), the Iranian Office of Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse has recently acknowledged that the prevention and treatment of substance abuse disorders should be included in the disaster preparedness, response, and recovery phases, but empirical information on how to perform these approaches is scarce. The disasters can cause individual and social harm, which can increase stress. People react to these adverse effects in different ways, such as the use of drugs [33]. The support programs for substance abuse prevention can be provided to people who were drug addict before disasters and to people who are at risk of drug addiction followed by experiencing disasters. The CBHOs/NGOs can participate in providing these support programs by preparing trained volunteers who can screen and identify the groups at risk of addiction and provide pre-disaster treatment (cognitive-behavioral therapy) and post-disaster plans to reduce substance use (assertive community treatment) [34]. However, it is important to know how to handle clients’ resistance and manage scarce resources.

Women and girls are more vulnerable during disasters, especially those who do not have a legal guardian. There are several reports of gender discrimination in providing relief services, women’s less access to information and resources, and gender poverty. At the political level, the opinions of women about disaster management are not sufficiently considered, indicating the need for education in this field. There is also growing evidence of increased violence against women and girls during and after disasters [35, 36], including non-partner or partner violence, rape, honor killings, and trafficking. There were reports of widespread rape after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and a 40% increase in partner sexual violence after the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand [36]. Increased violence against women and girls after disasters may have adverse health consequences for them throughout their lives. It can lead to unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infections, physical injuries, various mental health issues, and even murder or suicide. Decreased facilities and low access to health and emergency services can delay the delivery of timely and quality treatment and potentially worsen health outcomes [37]. In line with the fifth objective, Hossain et al. also recommended the participation of women in CBOs to provide them with more information about their rights through proper education and enhance their disaster resilience [38]. In this regard, it is necessary to teach all CBOs and NGOs about practical measurements in this field.

Based on the sixth objective, the mental health of volunteer groups and deployed workers should be improved before disasters. Affected communities may experience anxiety, sadness, fear, interpersonal conflict, and anger and show physical reactions such as changes in eating habits, sleep quality, stomach pain, and increased alcohol or drug use [39]. Regarding the fact that Iran is one of the disaster-prone countries in the world [40], preparedness for the mental health consequences of disasters in this country is more important. Therefore, the development of action plans and programs aimed at strengthening the mental resilience of at-risk communities is essential to help them know how to deal with potential psychological disorders [39]. Laborde et al. used the train-the-trainer model for training community leaders and indicated that the culturally relevant component-based workshops facilitated the recruitment for disaster participation of volunteers and extended trainer support in future field trials [41]. Therefore, educational courses for the volunteers on how to communicate and interact with affected communities are significant to prevent further adverse effects.

Ethical guidance, along with legal and medical frameworks, is one of the most common component of disaster response plans. The purpose of the ethical guidelines is to strengthen the disaster resilience by giving ethical content to sustainable development, human rights and human vulnerability related to gender, society, and environment [42]. Due to the universal nature of ethical principles, they involve all parties, including the victims, in responding to disasters at any time and place. Fundamental human rights should be exercised periodically, and there are no exceptions for volunteer first responders. During emergencies, sometimes there is a need to make decisions that can be morally difficult; disaster relief workers need to be prepared to deal with the situation. Raising awareness of moral problems that disaster responders may face can increase participation, as ethical awareness helps better problem-solving during a disaster. Therefore, based on the seventh objective, a culture of resilience accompanied by the observation of human rights can help develop a “code of ethics” that is important for preventing the devastating effects of disasters [43].

Morale is a psychological factor that leads to positive behaviors and increased work and performance [44]. A higher morale level seems to be associated with a more positive attitude and better coping with a disaster. Disasters always affect people’s financial and economic status. Welfare and morale are elements that contribute to disaster response management [45]. Improving the morale of volunteers, disaster responders, and victims can help people quickly recover. The potential role of morale has been neglected by researchers and organizations [45]. Gunessee et al. [46] concluded that a social preferences motivating framework can guide spontaneous voluntarism during relief operations. Therefore, based on the eighth objective, all disaster responders should receive training on how to improve the morale of affected people. Effective communication with patients and affected groups should also be taken into account (ninth objective), which can reduce complications and subsequent events [47]. The CBHOs/NGOs should communicate quickly and frequently with multiple stakeholders to prevent disaster panic and implement a regular response plan [48]. They are the gatekeepers of gathering first-hand information and can provide risk communication in responding to disasters [50]. To provide effective risk communication during a disaster, education should be provided to these organizations.

Although providing social services is one of the most important activities of CBOs during disasters, the lack of competence and capacity can cause devastating effects in a community. Therefore, they should acquire both legal approval and knowledge-based authentication in all the fields discussed above.

Conclusion

One of the challenging aspects of establishing and launching CBHOs and NGOs in Iran is the lack of attention to their basic educational needs. Therefore, constant educational courses based on needs assessment are needed for these organizations. The permission for their activity extension should be subjected to passing specialized educational courses. In this study, the program syllabuses and educational strategies/teaching methods based on target groups were proposed for the CBHOs/NGOs in Iran to promote their participation in managing natural disasters. In this regard, the first focus should be on the conceptual foundations of CBHOs/NGOs to determine their role and social status, practical functions, and structure before participation in disaster management. The second focus should be on the SDH in developing rescue plans to create a culture of safety and improve social responsibility, social cohesion, drug addiction prevention, mental health, ethics in relief operations, morale of the affected people, patient communication, and women’s need fulfillment. We recommend these educational needs for all CBHOs/NGOs in Iran before participation in disaster management, which can help them manage donations, technical assistance, networking, resource utilization, and mobilizations. The designed educational program can be used in other countries after modifications based on local government requirements and structure.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUI.REC.1399.018).

Funding

This research was funded by the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (WHO-EMRO) (Grant No.: RPPH20-125).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and supervision: Mohammad H Yarmohammadian and Fatemeh Rezaei; Investigation: Fatemeh Rezaei; Data collection and writing: Faezeh Akbari and Asal Sadat Niaraees Zavare; Data analysis: Faezeh Akbari, Asal Sadat Niaraees Zavare, and Fatemeh Rezaei; Funding acquisition and resources: Mohammad H Yarmohammadian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for their invaluable support throughout this research. Special thanks to Mahmoud Keyvanara, the coordinator, for his exceptional guidance and assistance. The authors also wish to acknowledge Nasrin Shaarbafchizadeh, another coordinator, whose contributions were instrumental in the success of this project. Additionally, they are grateful to Golrokh Atighechian, the external supervisor, for her insightful feedback and encouragement.

References

Community-based health organizations (CBHOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have a gatekeeping role where public participation can be achieved to promote community-based preparedness measures [1]. In developed countries, community-based organizations (CBOs) and faith-based organizations (FBOs) are the main partners of health systems as they are well-equipped with community knowledge, structure, and resources. They have received the necessary training in risk communication and building social trust in public organizations during disasters [2-4]. According to the Sendai framework, all countries should reduce the risk of disasters by 2030 and promote local cooperation and risk communications through CBOs and NGOs along with the use of knowledge, innovation, and education based on the Hyogo framework [5, 6]. Therefore, the training of NGOs/CBOs plays a vital role in providing early support and health services, disseminating important information, providing logistics services, and facilitating opportunities to discuss policies and operational plans in emergencies [7-9]. The CBOs/NGOs can help emergency management organizations access and manage social networks and voluntary resources [10]. Accordingly, specialized CBOs/NGOs can provide well-qualified health care and rehabilitation services to vulnerable groups when governments suffer from limited resources after disasters [11, 12].

To address the educational needs of a community, Takahashi et al. [13] and Prasetyo et al. [14] suggested that setting up of a school health is the most applicable strategy due to the inefficiency of practical training that only relies on successful interactive, inquiry-based, and experiential learning data. The continuous education of disaster risk reduction teachers is another challenge. Therefore, due to the gaps in disaster health risk literacy, Kagawa et al. [15] and Chan et al. [16] showed that it is necessary to develop a more systematized, reinforced, and sustainable educational program. Among the five main factors needed for the success of community participation identified by Enshassi et al. [17], the factors of risk perception, education and knowledge, and awareness of disaster management are directly influenced by community education. Hajito et al. [18] emphasized that communities with proper training and education have a higher ability to cope with disasters. In the same way, training provides a golden opportunity to develop the capabilities of CBOs/NGOs and their registered volunteers [19, 20] which led to less sensitiveness and responsibility of CBOs.

Community education is a cornerstone for fostering community partnerships and enhancing disaster management abilities. Also, education can improve the proficiency of CBOs/NGOs and their volunteers, equipping them with the tools to find and effectively mitigate the challenges posed by disasters. In this regard, in this qualitative study, we tried to develop a well-structured education program and answer the question, “What are the main concepts that CBHOs/NGOs in Iran should know before participating in managing disasters and emergency situations?”

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This qualitative study was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 25 key informants from 135 registered CBHOs and NGOs in Isfahan, Iran, with previous experience of cooperation with the health system in natural disasters who were experts in the field of social services. They were selected using purposive and snowball sampling methods. Snowball sampling was employed to identify the hard-to-reach key informants, as some of them were not registered workers in any organization (e.g. female volunteers) or had retired from their jobs. Moreover, 13 documents and instructions provided by the Iranian government to guide the participation of the non-government sector were also reviewed by two independent interviewers. In case of a dispute between them, the third researcher made the final decision. The content analysis method was used to identify the basic educational needs of CBHOs/NGOs before participating in disaster management. In the second phase, three focus group discussion (FGD) meetings were held to enrich and refine the main concepts identified in the first phase using a checklist. The key informants in FDG meetings were directors or members of the board of trustees of CBHOs, NGOs, or professors in disaster health and medical education.

Data collection and management

An interview guide was developed by the authors before conducting the interviews which included supporting items related to the goals, objectives, and syllabuses of an educational program for the organizations. The interview protocol was first tested as a pilot with the participation of five key informants who were not from among the participants. Finally, the interviews were conducted. Each interview lasted 30 minutes to an hour and was conducted in a location determined by the interviewees. All interviewees signed an informed consent form before recording their voices. We also obtained permission from the head of the institution and state government. The interview continued until reaching data saturation. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. After reaching the main categories, they were provided to interviewees to comment on the emerging concepts. The transcripts were entered into MAXQDA software, version 2018. Weekly sessions were held to analyze the transcriptions. The semantic units were coded and categorized. Throughout the coding process, the coders compared the codes and discussed disagreements. Finally, they came to an agreement on the final codes (a 97.6% agreement). Credibility was achieved after reviewing the literature and participating in CBHOs/NGOs coalition meetings.

In the second phase, the thematic content analysis led to a curriculum design that translates categories of educational needs into goals and objectives of the curriculum. Other components of the curriculum, such as syllabus, duration, budgeting, teaching methods/strategies, duration, and target groups were designed according to the curriculum development process. In this phase, the research team considered all the misconceptions and made reasonable changes in the main concepts until reaching the cohesion of goals, syllabuses, teaching strategies/methods, and evaluation tools. The experts had enough time (two weeks) to provide any suggestions in a WhatsApp group and discuss more details to reach a mutual agreement. Adjusting teaching methods/strategies based on the syllabuses and related goals was the most challenging part. In this regard, the research team elicited the opinions of participating experts and other experts in the field of education. The designed curriculum was finally reviewed and validated by experts.

Results

Participants included 17 members of the CBHOs’ board of trustees and 8 community plan liaison officers of NGOs. They were in the age range of 45-81 years. The majority of them were male (n=17, 5%) and had master’s degrees in nursing or were undergraduates and graduates, with 4-35 years of experience in the CBHOs.

In the first phase, the extracted main theme was “The theoretical concept, social role, official position, and structure of CBHOs/NGOs in disasters”. Two categories (goals) and 12 sub-categories (objectives) were extracted after analysis (Table 1).

The first goal was to recognize the conceptual foundations of the CBHOs and NGOs before participation in disaster management through three corresponding objectives. The second goal was to consider the social determinants of health (SDH) to help organizations have safe and secure plans based on nine objectives. Each objective was defined based on budget, time, educational strategies/teaching methods, and target groups (Table 2).

Discussion

The role and social status of HCBOs/NGOs participating in disaster management have been growing, which has made it difficult for the governments to manage. They have emerged as exigent sectors for disaster management. These organizations enhance communication and accelerate collective actions to improve community resilience and social/environmental goals [21]. Therefore, based on the first subcategory (objective) of the first category (goal) identified in this study, educational courses should make HCBOs/NGOs aware of their social impacts on affected communities after disasters. They should not act beyond the pre-defined roles and tasks in which they have no expertise to avoid adverse effects. Moreover, the structures of HCBOs/NGOs vary in hierarchies from a relatively strong central authority to a more loos local arrangement. Alternatively, they may be based in a single country and operate transnationally. Based on the second subcategory (objective), with the improvement in structure, more HCBOs/NGOs can become active at the national or even the global level [22]. Therefore, the educational program in this study for these organizations is not just to hold some classes without any theoretical and conceptual framework that can influence their work. Without a framework, it becomes difficult for field workers to effectively transfer knowledge and share experiential learning in any location, status, background, or expertise. The classification of participatory approaches for disaster management (the third objective) has also been recommended by the United Nations agencies [23]. The HCBOs/NGOs are well-recognized providers of social, educational and health services in partnership with private and public actors. We recommend these practice-based goals and objectives for CBHOs/NGOs to be more knowledgeable of their roles.

Based on the second category (goal) identified in this study with nine subcategories (objectives), which was the consideration of SDH in education, the first objective was to build a culture of safety in society, which refers to the product of values and attitudes in employees, managers, customers, and community members that determine the safety in dangerous situations, and all organizations should have a stake in it. In the response phase of disaster management, each individual and each organization should be aware of the unknown risks and dangers caused by various activities [24]. Education in safety culture can satisfy individuals and organizations and reduce casualties in the event of a disaster [25, 26]. Educational courses should aim to create spontaneous behaviors in volunteer groups and organizations and enhance safety to adapt to disasters. Inspiring volunteers to have a strong sense of social responsibility was the second objective, which is a key principle in reducing disaster risk and creating resilience. One way to improve the capacity and accountability of the health system in disasters in line with the second priority of the Sendai framework regarding disaster risk governance is to increase the quantity and quality of volunteers by using clients and students as organizations’ volunteers [27, 28]. In developed countries, disaster management relies highly on professionals. Given the increased risk of disasters worldwide [29], it is likely that volunteers can increase the capacity needed to respond to emergencies and disasters in the future. If communities want to maintain or increase their resilience to disasters and thus reduce their vulnerability, the motivational and social resources that lead to citizens’ participation in disasters should be defined well. To strengthen voluntary participation in disasters, the importance of motivation factor for volunteerism should be taught in educational courses to create the right conditions for further participation.

Social cohesion is an important factor in the welfare of society, especially in the time of disasters. Based on the third objective, the emergent social cohesion managed by social media can play an important role in improving communities’ ability to cope with disasters. Fan et al. also showed that during Hurricane Harvey, a good history of social cohesion in affected regions influenced communication and physical closeness [30]. Chowdhury showed that access to local loans provided by a CBO positively affected social cohesion during the recovery phase [31]. Samarakoon and Abeykoon showed that social cohesion can emerge as a latent function of a disaster and play an essential role in the victims’ recovery. According to them, receiving help from non-victims for more than three months may reduce psychosocial tension in victims [32]. Social cohesion in times of disasters is transparent in our country. However, donations are mostly sent in the first month. This somehow creates community dependency, but the sudden decline in donations has devastating effects on the community. Therefore, the volunteer groups need to be trained in this field.

In line with the fourth objective (drug addiction treatment planning), the Iranian Office of Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse has recently acknowledged that the prevention and treatment of substance abuse disorders should be included in the disaster preparedness, response, and recovery phases, but empirical information on how to perform these approaches is scarce. The disasters can cause individual and social harm, which can increase stress. People react to these adverse effects in different ways, such as the use of drugs [33]. The support programs for substance abuse prevention can be provided to people who were drug addict before disasters and to people who are at risk of drug addiction followed by experiencing disasters. The CBHOs/NGOs can participate in providing these support programs by preparing trained volunteers who can screen and identify the groups at risk of addiction and provide pre-disaster treatment (cognitive-behavioral therapy) and post-disaster plans to reduce substance use (assertive community treatment) [34]. However, it is important to know how to handle clients’ resistance and manage scarce resources.

Women and girls are more vulnerable during disasters, especially those who do not have a legal guardian. There are several reports of gender discrimination in providing relief services, women’s less access to information and resources, and gender poverty. At the political level, the opinions of women about disaster management are not sufficiently considered, indicating the need for education in this field. There is also growing evidence of increased violence against women and girls during and after disasters [35, 36], including non-partner or partner violence, rape, honor killings, and trafficking. There were reports of widespread rape after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and a 40% increase in partner sexual violence after the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand [36]. Increased violence against women and girls after disasters may have adverse health consequences for them throughout their lives. It can lead to unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infections, physical injuries, various mental health issues, and even murder or suicide. Decreased facilities and low access to health and emergency services can delay the delivery of timely and quality treatment and potentially worsen health outcomes [37]. In line with the fifth objective, Hossain et al. also recommended the participation of women in CBOs to provide them with more information about their rights through proper education and enhance their disaster resilience [38]. In this regard, it is necessary to teach all CBOs and NGOs about practical measurements in this field.

Based on the sixth objective, the mental health of volunteer groups and deployed workers should be improved before disasters. Affected communities may experience anxiety, sadness, fear, interpersonal conflict, and anger and show physical reactions such as changes in eating habits, sleep quality, stomach pain, and increased alcohol or drug use [39]. Regarding the fact that Iran is one of the disaster-prone countries in the world [40], preparedness for the mental health consequences of disasters in this country is more important. Therefore, the development of action plans and programs aimed at strengthening the mental resilience of at-risk communities is essential to help them know how to deal with potential psychological disorders [39]. Laborde et al. used the train-the-trainer model for training community leaders and indicated that the culturally relevant component-based workshops facilitated the recruitment for disaster participation of volunteers and extended trainer support in future field trials [41]. Therefore, educational courses for the volunteers on how to communicate and interact with affected communities are significant to prevent further adverse effects.

Ethical guidance, along with legal and medical frameworks, is one of the most common component of disaster response plans. The purpose of the ethical guidelines is to strengthen the disaster resilience by giving ethical content to sustainable development, human rights and human vulnerability related to gender, society, and environment [42]. Due to the universal nature of ethical principles, they involve all parties, including the victims, in responding to disasters at any time and place. Fundamental human rights should be exercised periodically, and there are no exceptions for volunteer first responders. During emergencies, sometimes there is a need to make decisions that can be morally difficult; disaster relief workers need to be prepared to deal with the situation. Raising awareness of moral problems that disaster responders may face can increase participation, as ethical awareness helps better problem-solving during a disaster. Therefore, based on the seventh objective, a culture of resilience accompanied by the observation of human rights can help develop a “code of ethics” that is important for preventing the devastating effects of disasters [43].

Morale is a psychological factor that leads to positive behaviors and increased work and performance [44]. A higher morale level seems to be associated with a more positive attitude and better coping with a disaster. Disasters always affect people’s financial and economic status. Welfare and morale are elements that contribute to disaster response management [45]. Improving the morale of volunteers, disaster responders, and victims can help people quickly recover. The potential role of morale has been neglected by researchers and organizations [45]. Gunessee et al. [46] concluded that a social preferences motivating framework can guide spontaneous voluntarism during relief operations. Therefore, based on the eighth objective, all disaster responders should receive training on how to improve the morale of affected people. Effective communication with patients and affected groups should also be taken into account (ninth objective), which can reduce complications and subsequent events [47]. The CBHOs/NGOs should communicate quickly and frequently with multiple stakeholders to prevent disaster panic and implement a regular response plan [48]. They are the gatekeepers of gathering first-hand information and can provide risk communication in responding to disasters [50]. To provide effective risk communication during a disaster, education should be provided to these organizations.

Although providing social services is one of the most important activities of CBOs during disasters, the lack of competence and capacity can cause devastating effects in a community. Therefore, they should acquire both legal approval and knowledge-based authentication in all the fields discussed above.

Conclusion

One of the challenging aspects of establishing and launching CBHOs and NGOs in Iran is the lack of attention to their basic educational needs. Therefore, constant educational courses based on needs assessment are needed for these organizations. The permission for their activity extension should be subjected to passing specialized educational courses. In this study, the program syllabuses and educational strategies/teaching methods based on target groups were proposed for the CBHOs/NGOs in Iran to promote their participation in managing natural disasters. In this regard, the first focus should be on the conceptual foundations of CBHOs/NGOs to determine their role and social status, practical functions, and structure before participation in disaster management. The second focus should be on the SDH in developing rescue plans to create a culture of safety and improve social responsibility, social cohesion, drug addiction prevention, mental health, ethics in relief operations, morale of the affected people, patient communication, and women’s need fulfillment. We recommend these educational needs for all CBHOs/NGOs in Iran before participation in disaster management, which can help them manage donations, technical assistance, networking, resource utilization, and mobilizations. The designed educational program can be used in other countries after modifications based on local government requirements and structure.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUI.REC.1399.018).

Funding

This research was funded by the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (WHO-EMRO) (Grant No.: RPPH20-125).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and supervision: Mohammad H Yarmohammadian and Fatemeh Rezaei; Investigation: Fatemeh Rezaei; Data collection and writing: Faezeh Akbari and Asal Sadat Niaraees Zavare; Data analysis: Faezeh Akbari, Asal Sadat Niaraees Zavare, and Fatemeh Rezaei; Funding acquisition and resources: Mohammad H Yarmohammadian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for their invaluable support throughout this research. Special thanks to Mahmoud Keyvanara, the coordinator, for his exceptional guidance and assistance. The authors also wish to acknowledge Nasrin Shaarbafchizadeh, another coordinator, whose contributions were instrumental in the success of this project. Additionally, they are grateful to Golrokh Atighechian, the external supervisor, for her insightful feedback and encouragement.

References

- Abrams LS, Shannon SKS, Sangalang C. Transition services for incarcerated youth: A mixed methods evaluation study.Children and Youth Services Review. 2008; 30(5):522-32. [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.11.003]

- McElfish PA, Rowland B, Hall S, CarlLee S, Reece S, Macechko MD, et al. Comparing community-driven covid-19 vaccine distribution methods: Faith-based organizations vs. outpatient clinics. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2022; 11(10):6081-6.[DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_327_22] [PMID]

- Levin J, Idler EL, VanderWeele TJ. Faith-based organizations and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Challenges and recommendations. Public Health Reports. 2022; 137(1):11-16. [PMID]

- Soni GK, Bhatnagar A, Gupta A, Kumari A, Arora S, Seth S, et al. Engaging faith-based organizations for promoting the uptake of COVID-19 Vaccine in India: A case study of a multi-faith society. Vaccines (Basel). 2023; 11(4):837. [DOI:10.3390/vaccines11040837] [PMID]

- UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030. Geneva: UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction; 2015. [Link]

- UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters. Geneva: UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction; 2007. [Link]

- Wieland ML, Asiedu GB, Njeru JW, Weis JA, Lantz K, Abbenyi A, et al. Community-engaged bidirectional crisis and emergency risk communication with immigrant and refugee populations during the covid-19 pandemic. Public Health Reports. 2022; 137(2):352-61. [DOI:10.1177/00333549211065514] [PMID]

- Eller W, Gerber BJ, Branch LE. Voluntary Nonprofit Organizations and disaster management: Identifying the nature of inter-sector coordination and collaboration in disaster service assistance provision. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy. 2015; 6(2):223-38. [DOI:10.1002/rhc3.12081]

- Sayarifard A, Nazari M, Rajabi F, Ghadirian L, Sajadi HS. Identifying the Non-Governmental Organizations’ activities and challenges in response to the covid-19 pandemic in Iran.BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):704. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-022-13080-5] [PMID]

- Waldman S, Yumagulova L, Mackwani Z, Benson C, Stone J. Canadian citizens volunteering in disasters: From emergence to networked governance. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2018; 26(3):394-402. [DOI:10.1111/1468-5973.12206]

- Ali A, Khan A. Benefits of community based organizations for community development. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies. 2014; 5(2):89-93. [Link]

- Yakubovich AR, Sherr L, Cluver LD, Skeen S, Hensels IS, Macedo A, et al. Community-based organizations for vulnerable children in South Africa: Reach, psychosocial correlates, and potential mechanisms, Children and Youth Services Review. 2016; 62:58-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.01.016] [PMID]

- Takahashi K, Kodama M, Gregorio ER, Tomokawa S, Asakura T, Waikagul J, et al. School Health: An essential strategy in promoting community resilience and preparedness for natural disasters. Global Health Action. 2015; 8:29106.[DOI:10.3402/gha.v8.29106] [PMID]

- Prasetyo I, Tohani E, Suharta RB. Model of integrated disaster awareness community to Community Learning Center (CLC) in Bantul and Sleman Distric BT. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference for Science Educators and Teachers. 2017; 675-80. [DOI:10.2991/icset-17.2017.112]

- Selby D, Kagawa F. Disaster risk reduction in school curricula: Case studies from thirty countries. Paris: Unesco; 2012. [Link]

- Chan EYY, Hung KKC, Yue JSK, Kim JH, Lee PPY, Cheung EYLCheung, et al. Preliminary findings on urban disaster risk literacy and preparedness in a Chinese Community. Paper presented at: The 13th World Congress on Public Health.April 2012 ;Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Link]

- Enshassi A, Shakalaih S, Mohamed S. Success factors for community participation in the pre-disaster phase. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2019; 294. [DOI:10.1088/1755-1315/294/1/012027]

- Hajito KW, Gesesew HA, Bayu NB, Tsehay YE. Community awareness and perception on hazards in Southwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2015; 13:350-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.07.012]

- Rezaei F, Keyvanara M, Yarmohammadian MH. Participation’ goals of community- based organizations in the covid-19 pandemic based on capacity gaps: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2022; 11:336. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1672_21] [PMID]

- Engelman A, Guzzardo MT, Antolin Muñiz M, Arenas L, Gomez A. Assessing the Emergency Response Role of Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) serving people with disabilities and older adults in puerto rico post-hurricane maría and during the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2156. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19042156] [PMID]

- Park ES, Yoon DK. The Value of NGOs in disaster management and governance in South Korea and Japan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2022; 69:102739.[DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102739]

- Rezaei F, Maracy MR, Yarmohammadian MH, Keyvanara M. How can community-based health organisations play a role in biohazards? A thematic analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development. 2020; 30(1):47-61. [DOI:10.1080/02185385.2019.1709100]

- Al-Jazairi AF. Disasters and disaster medicine. In Subhy Alsheikhly A (editor). Essentials of accident and emergency medicine. Vienna: Intech Open; 2019. [Link]

- Nair S, Siddiqui N. Safety culture and basic risk management principles. Journal of Industrial Pollution Control. 2013.

- Pidgeon NF. Safety culture and risk management in organizations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1991; 22(1):129-40. [DOI:10.1177/0022022191221009]

- Blenner SR, Lang CM, Prelip ML. Shifting the culture around public health advocacy: Training future public health professionals to be effective agents of change. Health Promotion Practice. 2017; 18(6):785-8. [DOI:10.1177/1524839917726764] [PMID]

- Kapucu N, Augustin ME, Krause M. Capacity building for community-based small nonprofit minority health agencies in Central Florida.The International Journal of Volunteer Administration. 2007; XXIV(3):10-17. [Link]

- Chong M. Employee participation in CSR and corporate identity: Insights from a disaster-response program in the Asia-Pacific. Corporate Reputation Review. 2009; 12:106-19. [DOI:10.1057/crr.2009.8]

- Rezaei F, Maracy MR, Yarmohammadian MH, Sheikhbardsiri H. Hospitals preparedness using WHO guideline : A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018; 25(4):211-22. [DOI:10.1177/1024907918760123]

- Fan C, Jiang Y, Mostafavi A. Emergent social cohesion for coping with community disruptions in disasters. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2020; 17(164):20190778. [DOI:10.1098/rsif.2019.0778] [PMID]

- M Chowdhury. Social cohesion and natural disaster loss recovery of households: Experience from Bangladesh [internet]. 2011 [Updated 2024 December 22]. vailable FROM: [Link]

- Samarakoon U, Abeykoon W. Emergence of social cohesion after a disaster: (With Reference to two flood affected locations in Colombo District-Sri Lanka). Procedia Engineering. 2018; 212:887-93. [DOI:10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.114]

- Kopak AM, Van Brown B. Substance use in the life cycle of a disaster: A research agenda and methodological considerations. American Behavioral Scientist. 2020; 64(8):1095-110. [DOI:10.1177/00027642209381]

- Amodeo M, Lundgren L, Cohen A, Rose D, Chassler D, Beltrame C, et al. Barriers to implementing evidence-based practices in addiction treatment programs: Comparing staff reports on motivational interviewing, adolescent community reinforcement approach, assertive community treatment, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2011; 34(4):382-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.02.005] [PMID]

- True J. Gendered violence in natural disasters: Learning from New Orleans, Haiti and Christchurch. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work. 2016; 25(2):78–89. [DOI:10.11157/anzswj-vol25iss2id83]

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). Unseen, unheard: Gender-based violence in disasters. Geneva: IFRC; 2015. [Link]

- Thurston AM, Stöckl H, Ranganathan M. Natural hazards, disasters and violence against women and girls: A global mixed- methods systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2021; 6(4):e004377. [DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004377] [PMID]

- Hossain BR, Hassan SK, Islam S, Nabi FD. Empowering the vulnerable women in disaster Prone Areas: A case study of Southern and Northern Region of Bangladesh. IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science. 2017; 22(9):14-21. [Link]

- WHO. Health services must stop leaving older people behind. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Link]

- Khankeh HR, Khorasani-Zavareh D, Johanson E, Mohammadi R, Ahmadi F, Mohammadi R. Disaster health related challenges and requirements: A grounded theory study in Iran. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2011; 26(3):151-8. [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X11006200] [PMID]

- Laborde DJ, Magruder K, Caye J, Parrish T. Feasibility of disaster mental health preparedness training for black communities. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2013; 7(3):302-12. [DOI:10.1001/dmp.2012.18] [PMID]

- Leider JP, DeBruin D, Reynolds N, Koch A, Seaberg J. Ethical guidance for disaster response, specifically around crisis standards of care: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health. 2017; 107(9):e1-9. [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303882] [PMID]

- Prieur M. Ethical principles on disaster risk reductionand people’s resilience. European and Mediterranean Major Hazards Agreement (EUR-OPA). Strasbourg: Democracy Council of Europe; 2015. [Link]

- Mallik A, Mallik L, Keerthi D. Impact of employee morale on organizational success. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE). 2019; 8(4):3289-93. [Link]

- Roslan NH, Abdullah H, Mohamed R. Relationship between welfare and morale of infantry personnel with disaster response management. ZULFAQAR Journal of Defence Management, Social Science& Humanities. 2021; 4(2):98-104. [Link]

- Eshel Y, Kimhi S, Marciano H, Adini B. Morale and perceived threats as predictors of psychological coping with distress in pandemic and armed conflict times. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8759. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18168759] [PMID]

- Gunessee S, Subramanian N, Roscoe S, Ramanathan J. The social preferences of local citizens and spontaneous volunteerism during disaster relief operations. International Journal of Production Research. 2017; 56(21):6793-808. [DOI:10.1080/00207543.2017.1414330]

- Sellnow TL, Sellnow DD, Lane DR, Littlefield RS. The value of instructional communication in crisis situations: Restoring order to chaos. Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of The Society for Risk Analysis. 2012; 32(4):633-43. [DOI:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01634.x] [PMID]

- Kapucu N, Yuldashev F, Feldheim MA. Nonprofit organizations in disaster response and management: A network analysis. Journal of Economics and Financial Analysis. 2018; 2(1):69-98. [DOI:10.1991/jefa.v2i1.a13]

- Khairi Zahari R, Raja Ariffin RN. Community-based disaster management in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 85:493-501. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.378]

Type of article: Research |

Subject:

Qualitative

Received: 2024/01/6 | Accepted: 2024/07/20 | Published: 2025/01/1

Received: 2024/01/6 | Accepted: 2024/07/20 | Published: 2025/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |