Volume 11, Issue 2 (Winter 2026)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2026, 11(2): 139-150 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR. TBZMED.REC.1399.1079

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Javanmardi K, Feizollahzadeh H, Gilani N, Dadashzadeh A, Dehghannejad J. Exposure Risk Assessment and Management of Pre-hospital Paramedics During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2026; 11 (2) :139-150

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-617-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-617-en.html

Karim Javanmardi1

, Hosein Feizollahzadeh2

, Hosein Feizollahzadeh2

, Neda Gilani3

, Neda Gilani3

, Abbas Dadashzadeh *4

, Abbas Dadashzadeh *4

, Javad Dehghannejad2

, Javad Dehghannejad2

, Hosein Feizollahzadeh2

, Hosein Feizollahzadeh2

, Neda Gilani3

, Neda Gilani3

, Abbas Dadashzadeh *4

, Abbas Dadashzadeh *4

, Javad Dehghannejad2

, Javad Dehghannejad2

1- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran.

2- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

3- Department of Statistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Health, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. & Medical Education Research Center, Health Management and Safety Promotion Research Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

4- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. ,ddshzd@yahoo.com

2- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

3- Department of Statistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Health, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. & Medical Education Research Center, Health Management and Safety Promotion Research Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

4- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 596 kb]

(232 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (601 Views)

Full-Text: (30 Views)

Introduction

Pre-hospital emergency medical technicians or paramedics provide medical care in diverse, unique, uncontrolled, and dangerous environments [1]. Accordingly, they encounter numerous infectious patients with unknown histories who require urgent treatment, which may expose them to infectious diseases [2]. Because of caring for patients and providing emergency care, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), suctioning and intubation, paramedics are at high risk of infectious diseases [3]. Therefore, paramedics risk management and safety is an important issue in emergency management.

Exposure risk is defined as contact with a suspected or infected COVID-19 patient without the use of standard personal protective equipment (PPE) components by pre-hospital paramedics [4], while risk management involves the activities undertaken to reduce exposure to COVID-19 [5].

During the recent COVID-19 pandemic crisis, pre-hospital paramedics were the first healthcare providers for patients and played an important role in health outcomes [6]. They were placed at great risk to save patients’ lives [7, 8]. In a 2020 study by Ashinyo et al., in Ghana, 80.4% of pre-hospital personnel were at high COVID-19 exposure risk [9], and this rate was 32.7% in another study from Korea [10]. As an emerging and contagious disease, the COVID-19 pandemic reated a major challenge for pre-hospital paramedics that requires strict adherence to protocols [11]. During this time, emergency medical service (EMS) dispatch missions worldwide increased dramatically. Because paramedics encountered many infected patients, they were at higher risk of illness, and an unprecedented workload was imposed on them [6, 7, 12-15]. During this period, the number of missions to transport patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome and CPR increased by 56% and 58%, respectively [13-16]. To avoid infection, paramedics should strictly follow protocols and guidelines and use PPE [17]. They should take advantage of PPE to comply with standards when transporting or caring for patients with COVID-19 [17, 18]. The use of PPE was part of EMS standards when dealing with COVID-19 patients, which was recommended by World Health Organization (WHO) [19]. PPE offers different levels of protection depending on the nature of its components, which include gloves, face masks, N95 masks, face shields, protective clothing, etc. [20]. Adequate access to PPE components, as well as their proper and principled use, reduces the risk of occupational exposure to the disease for paramedics [6]. Lack of access to this equipment, along with insufficient knowledge and training, can cause irreparable harm to paramedics [21]. Subsequently, it is important to evaluate and manage the risk ratio among paramedics during the COVID-19 pandemic [22]. The provided information can help improve paramedic safety during emerging diseases and pandemic crises.

According to the Iran EMS system report, during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, daily calls to emergency medical care unit escalated unprecedentedly, and the number of missions increased by 35%, with 10-20% of daily missions dedicated to patients who were suspected or infected with COVID-19 [7]. However, the exposure risk rate, level of risk management, and safety of paramedics are not known in most cities of Iran. The aim of this study was to assess the exposure risk and risk management of paramedics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Tabriz and Urmia cities in Iran.

Materials and Methods

Design and samples

This descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted between March and May 2021. Data were collected from 49 rescue stations serving the metropolitan regions of Urmia and Tabriz located in northwestern of Iran with a total population of approximately 3,200,000 residents. In these regions, over 700,000 emergency calls are received by emergency medical centers annually, of which more than 150,000 result in emergency operations requiring the use of ambulances. The COVID-19 outbreak led to a sharp increase in the number of emergency calls and medical transports.

Sampling was done through a census; the sample size was equal to the population size, and all 335 pre-hospital paramedics employed in 49 emergency medical stations were selected. The inclusion criteria were a minimum of six months of work experience and prior experience caring for at least one patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 in the pre-hospital setting. Employees who worked part-time or in hospital emergency departments were not included in the study. Based on the exclusion criteria, questionnaires with more than 10% incomplete or missing responses were excluded from the analysis.

Data collection and tools

Data were collected using two questionnaires. The first questionnaire covered demographic and professional characteristics, such as age, marital status, highest level of qualification, history of COVID-19 infection (you and your family), work experience, hours worked per week, place of work, field of education, average number of missions, average number infected patients with COVID-19, and the median duration of contact with each patient.

The second questionnaire was adapted from a questionnaire developed by WHO to assess the risk and management of exposure to COVID-19. This tool is intended for healthcare facilities working with COVID-19 patients. It helps assess the risk to healthcare workers (HCWs) after exposure and provides recommendations for their management [23]. The questionnaire consists of three domains: Community exposure to the COVID-19 virus (2 items with yes/no responses), occupational exposure to the COVID-19 virus (6 items with yes/no responses), and adherence to infection prevention and control measures when in contact with suspected or infected COVID-19 patients (22 items with a four-point Likert scale response). This questionnaire assesses the type of activity in which the HCW is involved. In addition, it measures the level of risk based on low- or high-risk events. If an HCW answers “yes” to any of the activities reported in the community and occupational exposure subscales, the individual is considered to be at high risk of exposure to the COVID-19 virus. If an HCW responds with other options, the individual is assessed as being at high risk for infection with the COVID-19 virus [9, 24, 25].

To calculate the overall exposure risk score, one point was assigned to high-risk items and zero points to low-risk items. The sum of the overall scores from the questionnaire items was considered the individual’s total exposure risk score (score range=0-30). Finally, considering a score of 50%, values ≥15 were classified as high risk of exposure to COVID-19, while those <15 were classified as low risk of exposure [9].

In the present study, the questionnaires were first translated into Persian by a professional translator and then translated back into English by another professional translator. Both the translators and researchers evaluated all versions of the questionnaires, and the final Persian version was developed and approved through consensus after achieving good agreement for all items. For content validity, the Persian version was given to 10 professors from the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and their suggestions were taken into account. Additionally, face validity was assessed based on interviews with 10 pre-hospital paramedics. The reliability of the scale was assessed using Cronbach’s α coefficient in a pilot study involving 30 pre-hospital paramedics (α=0.89). These paramedics were not included in the research sample. To collect data, the questionnaires were administered online via Porsline, an online survey tool widely used in Iran. In coordination with the emergency services, contact information for paramedics was collected and the link to the questionnaires was distributed to participants via e-mail and social media, including WhatsApp, Telegram, and short message service (SMS). To maximize response rates, three reminder messages were sent over a two-month period. The response rate for the questionnaires was 90%. This methodology enabled the collection of a large dataset on the practical experiences of paramedics in treating COVID-19 patients in the pre-hospital setting.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, such as the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, as well as univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis using SPSS software, version 21.

Results

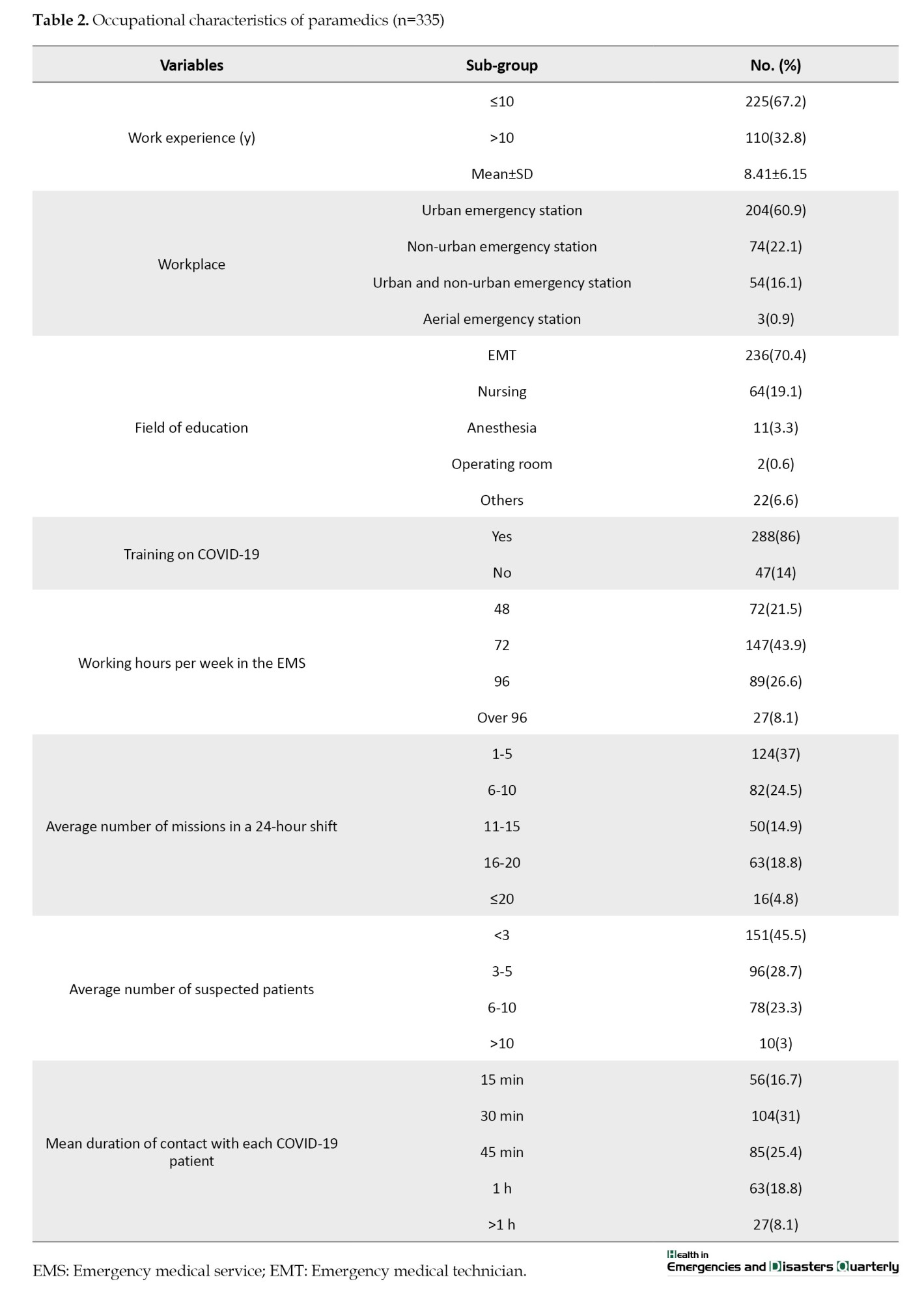

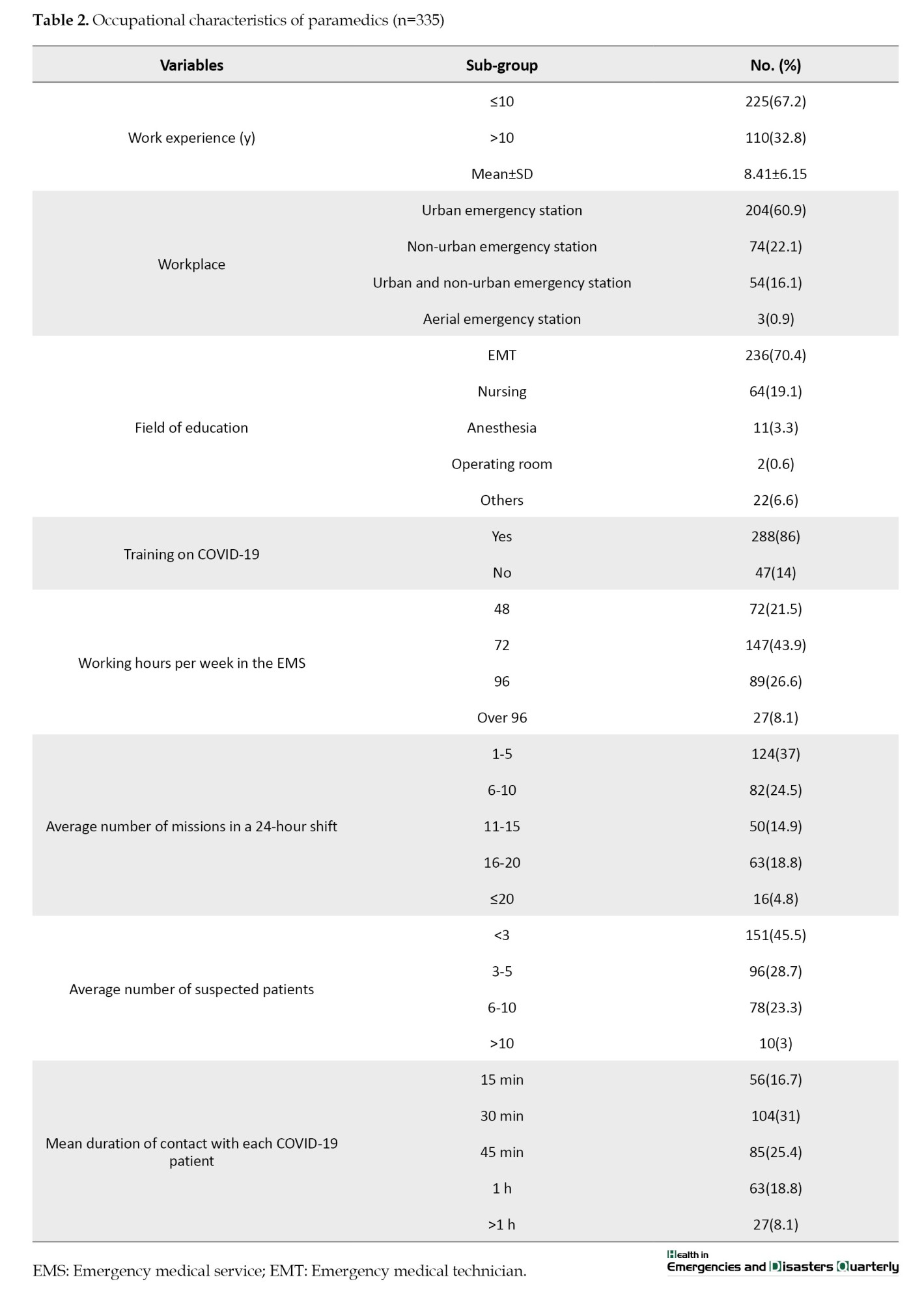

In this study, all participating pre-hospital paramedics were male with a mean age of 32.81±6.81 years and their mean work experience was 8.41±6.15 years. Over two-thirds (68.7%) of paramedics were married. Pre-hospital paramedics reported being in close contact with COVID-19 patients while providing care services, with a mean contact time of 30 minutes with each patient during emergency missions. Tables 1 and 2 provide further details on demographic features of participants.

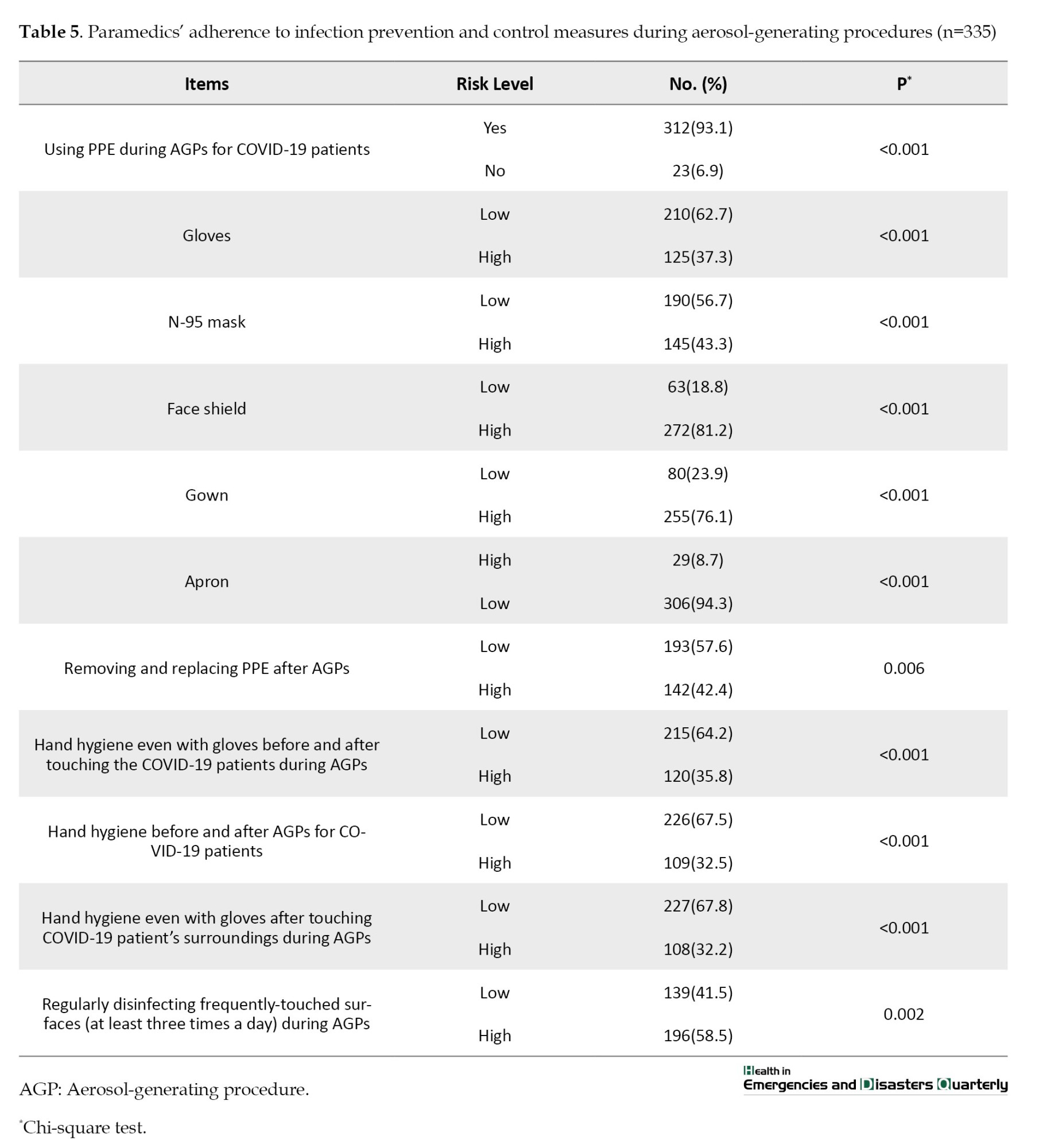

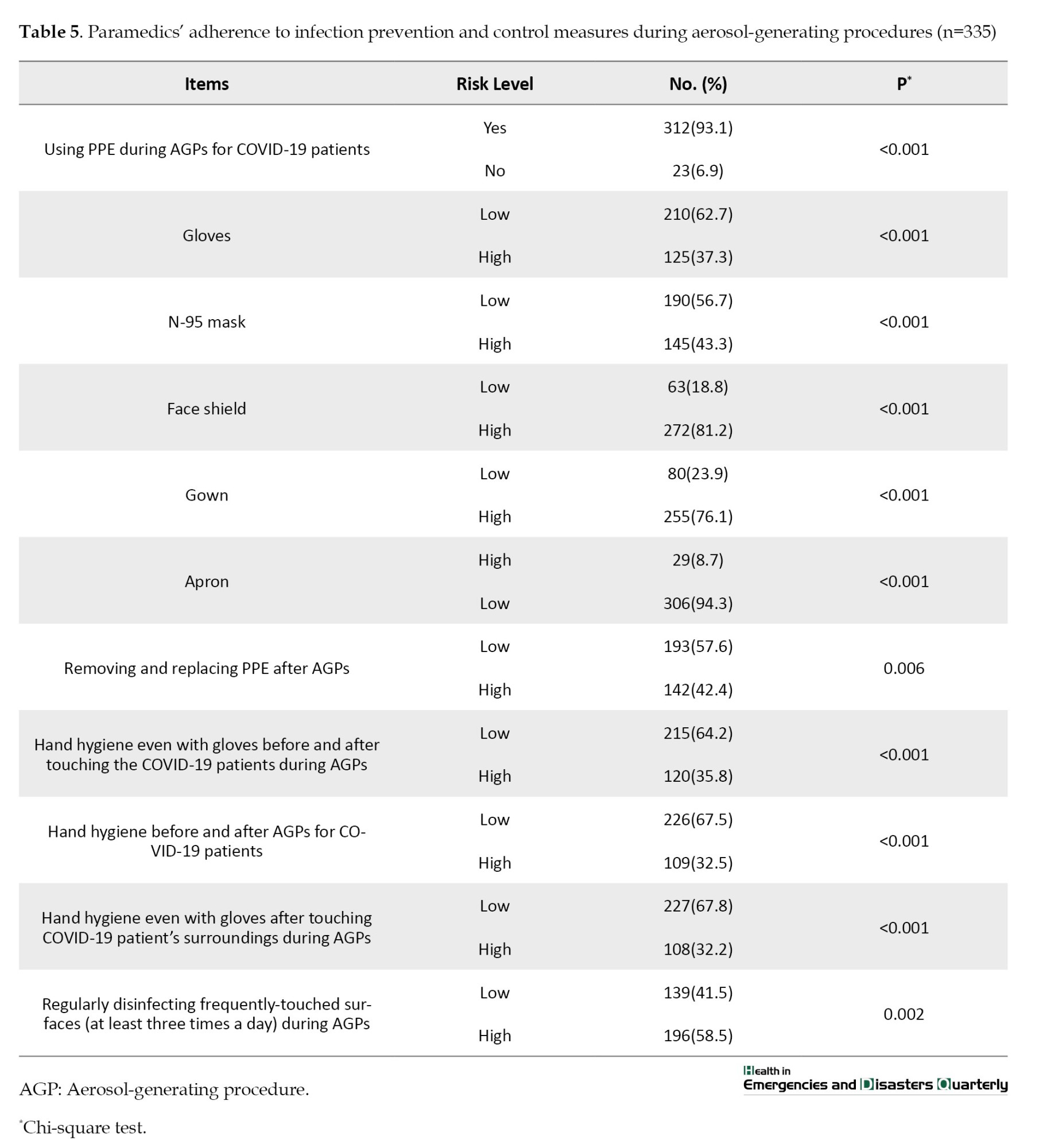

Regarding exposure to COVID-19, 93.4% of paramedics had a history of indoor contact with COVID-19 patients. Tables 3, 4, and 5 provide further details on participants’ exposure risk to COVID-19 and risk management.

In terms of exposure risk rate, the highest exposure risk (86.0%) was found in the domain of occupational exposure, and in general, 55.2% of paramedics were at high risk of exposure to COVID-19. Tables 6 and 7 provide further details on paramedics’ exposure risk rates and regression analyses.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that most pre-hospital paramedics were at high risk of exposure to COVID-19, and the highest risk of exposure was found in the domain of occupational exposure. Some paramedics and their families contracted COVID-19. Consistent with the present study, other investigations concluded that HCWs have high rates of exposure to COVID-19 [9, 10, 26, 27]. These results are also consistent with reports of previous epidemics, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) [20, 28].

The high risk of exposure to a contagious disease, such as COVID-19 should be managed appropriately as it can lead to infection, as well as psychological effects, such as burnout, reduced job satisfaction, intention to leave the job, etc. The results of a study showed that burnout was high among those who cared for long-term infected patients and among those who had a history of COVID-19 [29]. In this regard, Lee and Kim emphasized that relevant organizations and managers must focus on preventive measures in the workplace to control the pandemic [10]. Since pre-hospital paramedics are at the forefront of the emergency response to pandemic [6] and are at high risk of exposure in the workplace, it is recommended that they receive proper training and fully comply with infection control standards [20, 30].

In the present study, most paramedics adhered to infection prevention measures and used PPE when caring for patients and performing aerosol-generating procedures, which may lead to appropriate exposure risk management and improvement in their safety. While the results of some other studies indicated that compliance with infection prevention measures and the use of PPE by pre-hospital paramedics is challenging [1, 17].

Gulsen et al. reported a low prevalence of COVID-19 among pre-hospital emergency personnel in Turkey. They explained that timely provision of necessary PPE, regular work programs, planning multiple scenarios for unexpected situations, and involving staff in decision-making are effective in controlling the disease and reducing exposure among them [19]. Murphy et al. reported that to reduce occupational exposure in pre-hospital paramedics, the implementation of risk reduction strategies, adequate access to PPE, and the principled and proper application of it are the most effective measures [31].

In this study, the risk of exposure to COVID-19 was higher among staff who provided more intensive medical care to the infected patients. Given that prolonged contact with infected individuals increases the risk of illness [1], paramedics must use standard PPE and decrease the time spent with such patients as much as possible to improve their safety [1, 32].

Conclusion

Pre-hospital paramedics were at high risk of exposure to COVID-19, and the highest risk of exposure was found in the domain of occupational exposure. Hence, staff training, adequate access to PPE and training on its use, adherence to standards in implementing protective protocols, minimizing the length of stay for infected patients, and disinfecting ambulances and medical equipment will be helpful in preventing the spread of COVID-19 and reducing the risk of infection.

Limitations

This study relied on self-reported questionnaires to collect data and evaluate paramedics’ performance; therefore, there may be recall bias. Furthermore, the research was only conducted in the cities of Tabriz and Urmia in Iran, which limits the transferability to other regions of the country. Future studies using objective performance metrics across a larger geographic area would strengthen conclusions regarding paramedics’ competencies at a national level. In addition, the assessment was limited to the personnel of pre-hospital emergency service. Comparative analyzes of pre-hospital and hospital-based findings could provide valuable insights to optimize the continuity of care for patients with COVID-19. Another limitation of our study was online data collection; as a result, the accuracy and authenticity of the subjects may differ from those obtained in a field survey.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the regional research ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (Code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.1079). To collect the data, the necessary coordination was made with the responsible authorities. At the beginning of the questionnaire, there was a question about consent to participate in the study. While the necessary explanations were given to the paramedics, their informed consent to participate in the study was obtained. The principle of data confidentiality was respected by the researchers.

Funding

This study was taken from the master's thesis of Karim Javanmardi, approved by the Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing & Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, and writing the original draft: Karim Javanmardi; Data analysis and interpretation: Karim Javanmardi and Neda Gilani; Review and editing: Abbas Dadashzadeh, Hosein Feizollahzadeh, and Javad Dehghannejad; Final approval: Abbas Dadashzadeh; Supervision: Abbas Dadashzadeh, Hosein Feizollahzadeh, Neda Gilani, and Javad Dehghannejad;

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the dean of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and the officials of emergency services at Urmia and Tabriz for supporting this work. In addition, the authors would like to thank the paramedics who generously contributed their time and insights to this study.

Pre-hospital emergency medical technicians or paramedics provide medical care in diverse, unique, uncontrolled, and dangerous environments [1]. Accordingly, they encounter numerous infectious patients with unknown histories who require urgent treatment, which may expose them to infectious diseases [2]. Because of caring for patients and providing emergency care, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), suctioning and intubation, paramedics are at high risk of infectious diseases [3]. Therefore, paramedics risk management and safety is an important issue in emergency management.

Exposure risk is defined as contact with a suspected or infected COVID-19 patient without the use of standard personal protective equipment (PPE) components by pre-hospital paramedics [4], while risk management involves the activities undertaken to reduce exposure to COVID-19 [5].

During the recent COVID-19 pandemic crisis, pre-hospital paramedics were the first healthcare providers for patients and played an important role in health outcomes [6]. They were placed at great risk to save patients’ lives [7, 8]. In a 2020 study by Ashinyo et al., in Ghana, 80.4% of pre-hospital personnel were at high COVID-19 exposure risk [9], and this rate was 32.7% in another study from Korea [10]. As an emerging and contagious disease, the COVID-19 pandemic reated a major challenge for pre-hospital paramedics that requires strict adherence to protocols [11]. During this time, emergency medical service (EMS) dispatch missions worldwide increased dramatically. Because paramedics encountered many infected patients, they were at higher risk of illness, and an unprecedented workload was imposed on them [6, 7, 12-15]. During this period, the number of missions to transport patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome and CPR increased by 56% and 58%, respectively [13-16]. To avoid infection, paramedics should strictly follow protocols and guidelines and use PPE [17]. They should take advantage of PPE to comply with standards when transporting or caring for patients with COVID-19 [17, 18]. The use of PPE was part of EMS standards when dealing with COVID-19 patients, which was recommended by World Health Organization (WHO) [19]. PPE offers different levels of protection depending on the nature of its components, which include gloves, face masks, N95 masks, face shields, protective clothing, etc. [20]. Adequate access to PPE components, as well as their proper and principled use, reduces the risk of occupational exposure to the disease for paramedics [6]. Lack of access to this equipment, along with insufficient knowledge and training, can cause irreparable harm to paramedics [21]. Subsequently, it is important to evaluate and manage the risk ratio among paramedics during the COVID-19 pandemic [22]. The provided information can help improve paramedic safety during emerging diseases and pandemic crises.

According to the Iran EMS system report, during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, daily calls to emergency medical care unit escalated unprecedentedly, and the number of missions increased by 35%, with 10-20% of daily missions dedicated to patients who were suspected or infected with COVID-19 [7]. However, the exposure risk rate, level of risk management, and safety of paramedics are not known in most cities of Iran. The aim of this study was to assess the exposure risk and risk management of paramedics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Tabriz and Urmia cities in Iran.

Materials and Methods

Design and samples

This descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted between March and May 2021. Data were collected from 49 rescue stations serving the metropolitan regions of Urmia and Tabriz located in northwestern of Iran with a total population of approximately 3,200,000 residents. In these regions, over 700,000 emergency calls are received by emergency medical centers annually, of which more than 150,000 result in emergency operations requiring the use of ambulances. The COVID-19 outbreak led to a sharp increase in the number of emergency calls and medical transports.

Sampling was done through a census; the sample size was equal to the population size, and all 335 pre-hospital paramedics employed in 49 emergency medical stations were selected. The inclusion criteria were a minimum of six months of work experience and prior experience caring for at least one patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 in the pre-hospital setting. Employees who worked part-time or in hospital emergency departments were not included in the study. Based on the exclusion criteria, questionnaires with more than 10% incomplete or missing responses were excluded from the analysis.

Data collection and tools

Data were collected using two questionnaires. The first questionnaire covered demographic and professional characteristics, such as age, marital status, highest level of qualification, history of COVID-19 infection (you and your family), work experience, hours worked per week, place of work, field of education, average number of missions, average number infected patients with COVID-19, and the median duration of contact with each patient.

The second questionnaire was adapted from a questionnaire developed by WHO to assess the risk and management of exposure to COVID-19. This tool is intended for healthcare facilities working with COVID-19 patients. It helps assess the risk to healthcare workers (HCWs) after exposure and provides recommendations for their management [23]. The questionnaire consists of three domains: Community exposure to the COVID-19 virus (2 items with yes/no responses), occupational exposure to the COVID-19 virus (6 items with yes/no responses), and adherence to infection prevention and control measures when in contact with suspected or infected COVID-19 patients (22 items with a four-point Likert scale response). This questionnaire assesses the type of activity in which the HCW is involved. In addition, it measures the level of risk based on low- or high-risk events. If an HCW answers “yes” to any of the activities reported in the community and occupational exposure subscales, the individual is considered to be at high risk of exposure to the COVID-19 virus. If an HCW responds with other options, the individual is assessed as being at high risk for infection with the COVID-19 virus [9, 24, 25].

To calculate the overall exposure risk score, one point was assigned to high-risk items and zero points to low-risk items. The sum of the overall scores from the questionnaire items was considered the individual’s total exposure risk score (score range=0-30). Finally, considering a score of 50%, values ≥15 were classified as high risk of exposure to COVID-19, while those <15 were classified as low risk of exposure [9].

In the present study, the questionnaires were first translated into Persian by a professional translator and then translated back into English by another professional translator. Both the translators and researchers evaluated all versions of the questionnaires, and the final Persian version was developed and approved through consensus after achieving good agreement for all items. For content validity, the Persian version was given to 10 professors from the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and their suggestions were taken into account. Additionally, face validity was assessed based on interviews with 10 pre-hospital paramedics. The reliability of the scale was assessed using Cronbach’s α coefficient in a pilot study involving 30 pre-hospital paramedics (α=0.89). These paramedics were not included in the research sample. To collect data, the questionnaires were administered online via Porsline, an online survey tool widely used in Iran. In coordination with the emergency services, contact information for paramedics was collected and the link to the questionnaires was distributed to participants via e-mail and social media, including WhatsApp, Telegram, and short message service (SMS). To maximize response rates, three reminder messages were sent over a two-month period. The response rate for the questionnaires was 90%. This methodology enabled the collection of a large dataset on the practical experiences of paramedics in treating COVID-19 patients in the pre-hospital setting.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, such as the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, as well as univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis using SPSS software, version 21.

Results

In this study, all participating pre-hospital paramedics were male with a mean age of 32.81±6.81 years and their mean work experience was 8.41±6.15 years. Over two-thirds (68.7%) of paramedics were married. Pre-hospital paramedics reported being in close contact with COVID-19 patients while providing care services, with a mean contact time of 30 minutes with each patient during emergency missions. Tables 1 and 2 provide further details on demographic features of participants.

Regarding exposure to COVID-19, 93.4% of paramedics had a history of indoor contact with COVID-19 patients. Tables 3, 4, and 5 provide further details on participants’ exposure risk to COVID-19 and risk management.

In terms of exposure risk rate, the highest exposure risk (86.0%) was found in the domain of occupational exposure, and in general, 55.2% of paramedics were at high risk of exposure to COVID-19. Tables 6 and 7 provide further details on paramedics’ exposure risk rates and regression analyses.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that most pre-hospital paramedics were at high risk of exposure to COVID-19, and the highest risk of exposure was found in the domain of occupational exposure. Some paramedics and their families contracted COVID-19. Consistent with the present study, other investigations concluded that HCWs have high rates of exposure to COVID-19 [9, 10, 26, 27]. These results are also consistent with reports of previous epidemics, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) [20, 28].

The high risk of exposure to a contagious disease, such as COVID-19 should be managed appropriately as it can lead to infection, as well as psychological effects, such as burnout, reduced job satisfaction, intention to leave the job, etc. The results of a study showed that burnout was high among those who cared for long-term infected patients and among those who had a history of COVID-19 [29]. In this regard, Lee and Kim emphasized that relevant organizations and managers must focus on preventive measures in the workplace to control the pandemic [10]. Since pre-hospital paramedics are at the forefront of the emergency response to pandemic [6] and are at high risk of exposure in the workplace, it is recommended that they receive proper training and fully comply with infection control standards [20, 30].

In the present study, most paramedics adhered to infection prevention measures and used PPE when caring for patients and performing aerosol-generating procedures, which may lead to appropriate exposure risk management and improvement in their safety. While the results of some other studies indicated that compliance with infection prevention measures and the use of PPE by pre-hospital paramedics is challenging [1, 17].

Gulsen et al. reported a low prevalence of COVID-19 among pre-hospital emergency personnel in Turkey. They explained that timely provision of necessary PPE, regular work programs, planning multiple scenarios for unexpected situations, and involving staff in decision-making are effective in controlling the disease and reducing exposure among them [19]. Murphy et al. reported that to reduce occupational exposure in pre-hospital paramedics, the implementation of risk reduction strategies, adequate access to PPE, and the principled and proper application of it are the most effective measures [31].

In this study, the risk of exposure to COVID-19 was higher among staff who provided more intensive medical care to the infected patients. Given that prolonged contact with infected individuals increases the risk of illness [1], paramedics must use standard PPE and decrease the time spent with such patients as much as possible to improve their safety [1, 32].

Conclusion

Pre-hospital paramedics were at high risk of exposure to COVID-19, and the highest risk of exposure was found in the domain of occupational exposure. Hence, staff training, adequate access to PPE and training on its use, adherence to standards in implementing protective protocols, minimizing the length of stay for infected patients, and disinfecting ambulances and medical equipment will be helpful in preventing the spread of COVID-19 and reducing the risk of infection.

Limitations

This study relied on self-reported questionnaires to collect data and evaluate paramedics’ performance; therefore, there may be recall bias. Furthermore, the research was only conducted in the cities of Tabriz and Urmia in Iran, which limits the transferability to other regions of the country. Future studies using objective performance metrics across a larger geographic area would strengthen conclusions regarding paramedics’ competencies at a national level. In addition, the assessment was limited to the personnel of pre-hospital emergency service. Comparative analyzes of pre-hospital and hospital-based findings could provide valuable insights to optimize the continuity of care for patients with COVID-19. Another limitation of our study was online data collection; as a result, the accuracy and authenticity of the subjects may differ from those obtained in a field survey.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the regional research ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (Code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.1079). To collect the data, the necessary coordination was made with the responsible authorities. At the beginning of the questionnaire, there was a question about consent to participate in the study. While the necessary explanations were given to the paramedics, their informed consent to participate in the study was obtained. The principle of data confidentiality was respected by the researchers.

Funding

This study was taken from the master's thesis of Karim Javanmardi, approved by the Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing & Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, and writing the original draft: Karim Javanmardi; Data analysis and interpretation: Karim Javanmardi and Neda Gilani; Review and editing: Abbas Dadashzadeh, Hosein Feizollahzadeh, and Javad Dehghannejad; Final approval: Abbas Dadashzadeh; Supervision: Abbas Dadashzadeh, Hosein Feizollahzadeh, Neda Gilani, and Javad Dehghannejad;

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the dean of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and the officials of emergency services at Urmia and Tabriz for supporting this work. In addition, the authors would like to thank the paramedics who generously contributed their time and insights to this study.

References

- Alshammaria A, Baila JB, Parilloa SJ. PPE misuse and its effect on infectious disease among EMS in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Student Research. 2019; 8(1):51-8. [DOI:10.47611/jsr.v8i1.592]

- Costa M, Oberholzer-Riss M, Hatz C, Steffen R, Puhan M, Schlagenhauf P. Pre-travel health advice guidelines for humanitarian workers: A systematic review. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2015; 13(6):449-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.11.006] [PMID]

- Al-Shaqsi S. Models of international emergency medical service (EMS) systems. Oman Medical Journal. 2010; 25(4):320-3. [DOI:10.5001/omj.2010.92] [PMID]

- Kaur R, Kant S, Bairwa M, Kumar A, Dhakad S, Dwarakanathan V, et al. Risk stratification as a tool to rationalize quarantine of health care workers exposed to COVID-19 cases: Evidence from a tertiary health care center in India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2021; 33(1):134-7. [DOI:10.1177/1010539520977310] [PMID]

- Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS. Standardized risk assessment and management of exposure amongst healthcare workers to coronavirus disease 2019. Germs. 2020; 10(2):126-8. [DOI:10.18683/germs.2020.1196] [PMID]

- Ventura C, Gibson C, Collier GD. Emergency Medical Services resource capacity and competency amid COVID-19 in the United States: Preliminary findings from a national survey. Heliyon. 2020; 6(5):e03900. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03900] [PMID]

- Jalili M. How should emergency medical services personnel protect themselves and the patients during COVID-19 pandemic? Frontiers in Emergency Medicine. 2020; 4(2s):e37. [Link]

- Greenland K, Tsui D, Goodyear P, Irwin M. Personal protection equipment for biological hazards: Does it affect tracheal intubation performance? Resuscitation. 2007; 74(1):119-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.11.011] [PMID]

- Ashinyo ME, Dubik SD, Duti V, Amegah KE, Ashinyo A, Larsen-Reindorf R, et al. Healthcare workers exposure risk assessment: A survey among frontline workers in designated COVID-19 treatment centers in Ghana. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2020; 11:2150132720969483. [DOI:10.1177/2150132720969483] [PMID]

- Lee J, Kim M. Estimation of the number of working population at high-risk of COVID-19 infection in Korea. Epidemiology and Health. 2020; 42:e2020051. [DOI:10.4178/epih.e2020051] [PMID]

- Smereka J, Szarpak L. COVID 19 a challenge for emergency medicine and every health care professional. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020; 38(10):2232-3. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2m020.03.038] [PMID]

- Baldi E, Sechi GM, Mare C, Canevari F, Brancaglione A, Primi R, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the Covid-19 outbreak in Italy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020; 383(5):496-8. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMc2010418] [PMID]

- Ehrlich H, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Defending the front lines during the COVID-19 pandemic: Protecting our first responders and emergency medical service personnel. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021; 40:213-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.068] [PMID]

- Stella F, Alexopoulos C, Scquizzato T, Zorzi A. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on emergency medical system missions and emergency department visits in the Venice area. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020; 27(4):298-300. [DOI:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000724] [PMID]

- Cavaliere GA. COVID-19: Is now the time for EMS-initiated Refusal [Internet]? 2020 [Updated 2020 April 15]. Available from: [Link]

- Fernandez AR, Crowe RP, Bourn S, Matt SE, Brown AL, Hawthorn AB, et al. COVID-19 Preliminary case series: Characteristics of EMS encounters with linked hospital diagnoses. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2021; 25(1):16-27. [DOI:10.1080/10903127.2020.1792016] [PMID]

- Holland M, Zaloga DJ, Friderici CS. COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE) for the emergency physician. Visual Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020; 19:100740. [DOI:10.1016/j.visj.2020.100740] [PMID]

- Sprague RM, Ladd M, Ashurst JV. EMS resuscitation during contamination while wearing PPE. Treasure Island: StatPearls; 2018. [Link]

- Gulsen MF, Kurt M, Kaleli I, Ulasti A. Personal protective equipment (ppe) using in antalya 112 emergency ambulance services during outbreak. Journal of Emergency Medicine Trauma & Surgical Care. 2020; S1:002. [DOI:10.24966/ETS-8798/S1002]

- Visentin LM, Bondy SJ, Schwartz B, Morrison LJ. Use of personal protective equipment during infectious disease outbreak and nonoutbreak conditions: A survey of emergency medical technicians. CJEM. 2009; 11(1):44-56. [DOI:10.1017/S1481803500010915] [PMID]

- Maguire BJ, O’Neill BJ, Shearer K, McKeown J, Phelps S, Gerard DR, et al. The ethics of PPE and EMS in the COVID-19 era [Internet]. 2020 [Updated 2020 April 10]. Available from: [Link]

- Labrague LJ, de Los Santos JAA. Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. Journal of Nursing Management. 2021; 29(3):395-403. [DOI:10.1111/jonm.13168] [PMID]

- World Health Organization. Risk assessment and management of exposure of health care workers in the context of COVID-19: Interim guidance [Internet]. 2020 [Updated 2020 March 19]. Available from: [Link]

- Khalil MM, Alam MM, Arefin MK, Chowdhury MR, Huq MR, Chowdhury JA, et al. Role of personal protective measures in prevention of COVID-19 spread among physicians in Bangladesh: A multicenter cross-sectional comparative study. SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine. 2020; 2(10):1733-9. [DOI:10.1007/s42399-020-00471-1] [PMID]

- Bani-Issa WA, Al Nusair H, Altamimi A, Hatahet S, Deyab F, Fakhry R, et al. Self-report assessment of nurses' risk for infection after exposure to patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2021; 53(2):171-9. [DOI:10.1111/jnu.12625] [PMID]

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020; 323(11):1061-9. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.1585] [PMID]

- Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, Joshi AD, Guo CG, Ma W, et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet. Public Health. 2020; 5(9):e475-83. [DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X] [PMID]

- Oh HS, Uhm D. Occupational exposure to infection risk and use of personal protective equipment by emergency medical personnel in the Republic of Korea. American Journal of Infection Control. 2016; 44(6):647-51. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.12.022] [PMID]

- Sarboozi Hoseinabadi T, Kakhki S, Teimori G, Nayyeri S. Burnout and its influencing factors between frontline nurses and nurses from other wards during the outbreak of Coronavirus Disease -COVID-19- in Iran. Investigacion Y Educacion En Enfermeria. 2020; 38(2):e3. [DOI:10.17533/udea.iee.v38n2e03] [PMID]

- Adeleye OO, Adeyemi AS, Oyem JC, Akindokun SS, Ayanlade JI. Rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE) among health workers in COVID-19 frontline. European Journal of Pharmaceutical and Medical Research. 2020; 7(12):445-51. [Link]

- Murphy DL, Barnard LM, Drucker CJ, Yang BY, Emert JM, Schwarcz L, et al. Occupational exposures and programmatic response to COVID-19 pandemic: An emergency medical services experience. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2020; 37(11):707-13. [Doi:10.1136/Emermed-2020-210095] [PMID]

- Ko PC, Chen WJ, Ma MH, Chiang WC, Su CP, Huang CH, et al. Emergency medical services utilization during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the incidence of SARS-associated coronavirus infection among emergency medical technicians. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2004; 11(9):903-11. [DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2004.03.016] [PMID]

Protocol: Research |

Subject:

Risk assessment

Received: 2024/11/8 | Accepted: 2025/04/23 | Published: 2026/01/1

Received: 2024/11/8 | Accepted: 2025/04/23 | Published: 2026/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |