Volume 11, Issue 1 (Autumn 2025)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025, 11(1): 53-64 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nosratabadi M, Amini-Rarani M, Atighechian G. Are Iranian Medical Sciences Curricula Equipped to Effectively Respond to Incidents and Disasters? A Content Analysis. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025; 11 (1) :53-64

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-628-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-628-en.html

1- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Health Management and Economics Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Health in Disasters and Emergencies, Health Management and Economics Research Center, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,atighechian_golrokh@yahoo.com

2- Health Management and Economics Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Health in Disasters and Emergencies, Health Management and Economics Research Center, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 489 kb]

(471 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1904 Views)

Full-Text: (268 Views)

Introduction

We live in a world with rapidly accelerating hazards, both natural and man-made [1]. Disasters impact the lives of millions around the world and disrupt the development of nations and communities [2]. Between 2010 and 2014, 1,728 natural disasters occurred in the world alone, resulting in nearly 400,000 deaths and more than 850 billion USD in costs [3]. Also, in 2023, the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) documented 399 natural hazard-related disasters that caused 86,473 deaths and impacted 93.1 million individuals. The financial damages totaled 202.7 billion USD [4]. Iran is also a vulnerable and devastating disaster-prone nation [5]. Furthermore, the frequency and severity of many climate change-related disasters are expected to rise within the coming decades due to climate change and global warming [6]. Also, as threats develop, vulnerabilities grow, and new vulnerabilities arise.

The healthcare system in Iran and many other countries around the world faced one of the most important historical challenges in 2020 as a result of the worldwide epidemic of COVID-19. This emerging pandemic challenged not only many achievements in medical and health sciences but also a large number of social and political foundations, raising serious issues [7]. In this regard, Tripathi points out that the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of enhancing awareness and preparedness, particularly among healthcare providers [8]. Saffari-darberazi et al. also showed that one of the most significant infrastructures for hospital resilience against COVID-19 was the training and enhancement of the educational abilities of healthcare providers in hospitals [9].

Therefore, in such situations, it is vital to avoid the occurrence of hazards, mitigate their effects, and handle them effectively. Preparedness with modern knowledge of the types of hazards and methods of prevention is essential for an efficient response to disasters and emergencies. People who wish to be capable of responding adequately to disasters and emergencies must be educated in this crucial area. To minimize the effects of disasters, communities should be well informed of how to respond to disasters by health practitioners, and health practitioners primarily should be well educated in disaster management [10, 11]. According to studies, disaster education is a practical, operational, and cost-effective risk management method.

On the other hand, a great deal of study has been conducted on the educational needs of healthcare professionals in the event of disasters and emergencies. Studies conducted by Alhani and Jalalinia, Zarea et al., Nekooei Moghaddam et al., Taghizadeh et al., Pesiridis et al., and Oztekin et al. also confirm the high educational needs of healthcare providers to provide disaster services [12-17]. However, the level of preparedness of healthcare providers for disasters in many countries is inadequate [18]. This is also demonstrated by research in European countries, such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy [19-21], and is even more pronounced in developing countries, such as Yemen, Saudi Arabia, China, Ethiopia, and Malaysia [21-24]. Also, similar conditions exist in Iran [25].

However, to develop a policy document on disaster management training in the health sector and to implement training tasks in the field of disaster management law in Iran, plans are underway to create a course on “disaster risk reduction and preparedness” in the form of two compulsory courses for all medical science disciplines [26]. Developing a subject specific to the requirements of society and providing responsive education for this course primarily requires an analysis of current medical science curricula, focusing on the role of the concept of disaster. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the content of the official medical science curriculum from the perspective of disaster and emergencies.

Materials and Methods

In this qualitative content analysis study, the content of the official curricula of undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) of Iran was explored from a disasters and emergencies point of view. We considered each educational curriculum as a unit of analysis.

Screening

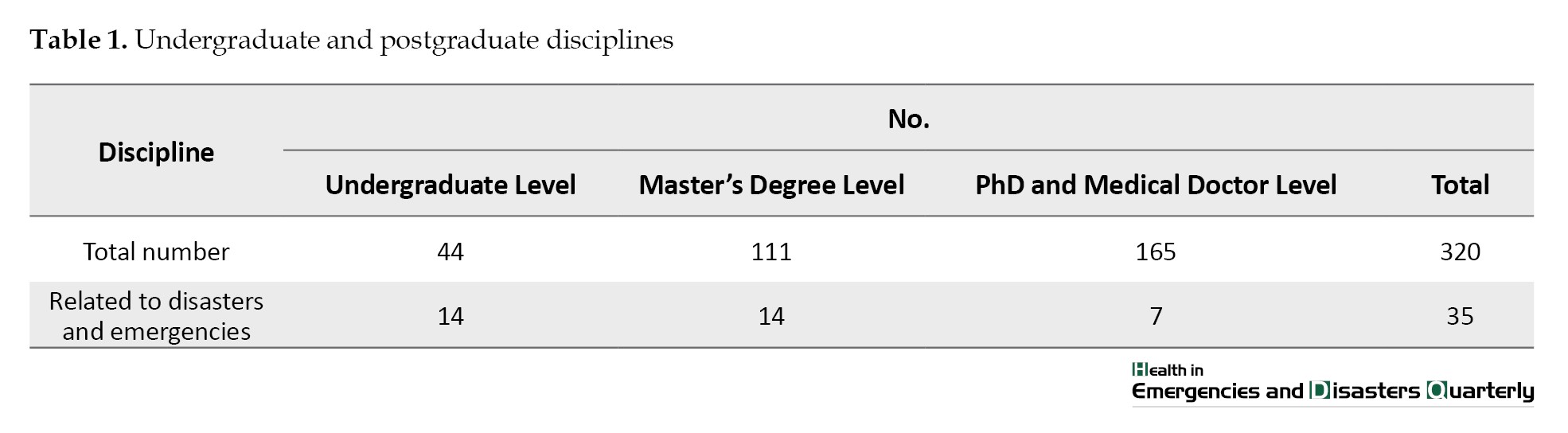

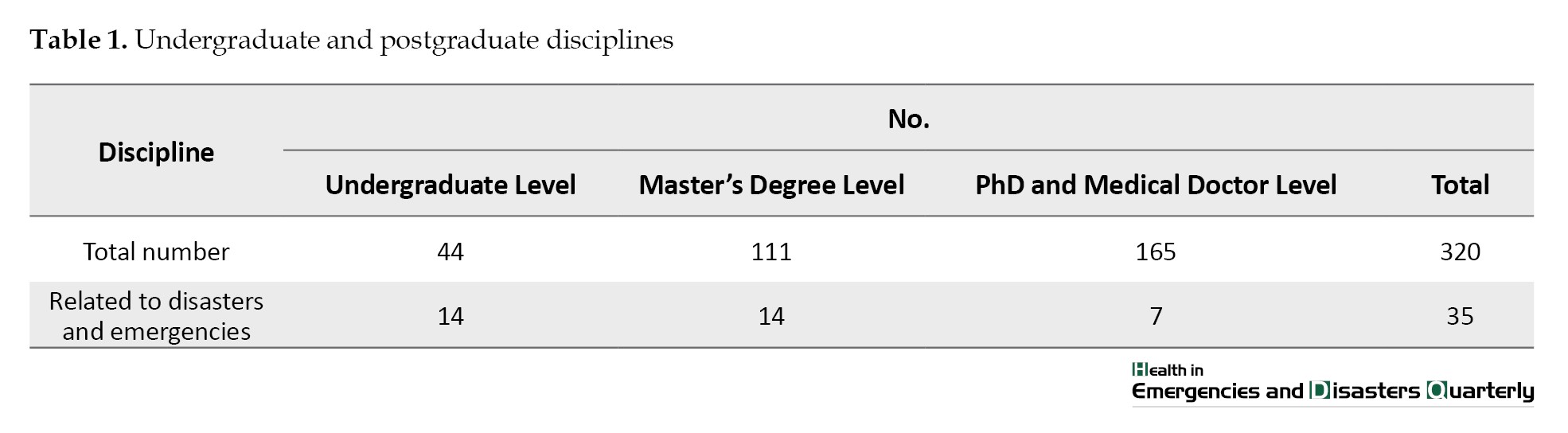

All undergraduate and postgraduate disciplines (320 courses) at MOHME of Iran were identified (Table 1).

The curricula of the disciplines were then screened based on the main concepts of disaster, incident, emergency, and disaster management. Consequently, disciplines unrelated to these concepts were excluded based on face validity (n=285). Finally, the remaining disciplines (n=35) were carefully reviewed and analyzed.

Qualitative content analysis

The conventional (inductive) content analysis approach [27] was used to analyze the content of curricula. Conventional (inductive) content analysis is a research methodology used to analyze and interpret the meaning of textual data. It is an inductive qualitative content analysis that involves a systematic and objective examination of the content to identify patterns, themes, and meanings. Here are the steps involved in the conventional content analysis approach:

Step 1: Research objectives

The objectives of this research were:

To analyze the content of Iranian medical sciences curricula;

To identify the extent to which the curricula address disaster response and management.

Step 2: Data collection

The researchers collected the medical sciences curricula from Offices of the Council for Medical, Pharmacy, Dentistry, Basic Sciences, Health, and Specialized Education on the Iranian MOHME website, which served as the data for the study.

Step 3: Data preparation

The curricula were reviewed, and relevant sections related to disaster response and management were extracted and organized for analysis.

Step 4: Coding

A coding scheme was developed to identify themes and concepts related to disaster response and management, such as: Disaster preparedness, emergency response, crisis management, disaster mitigation, and Public health emergency preparedness.

Step 5: Coding application

The coding scheme was applied to the extracted curriculum content, and codes were assigned to relevant segments of the text.

Step 6: Data analysis

The coded data were analyzed to identify patterns, themes, and relationships between the codes. The frequency, intensity, and context of the codes were examined to determine the emphasis placed on disaster response and management in the curricula.

Step 7: Theme identification

Themes emerged from the data analysis, such as: Lack of emphasis on disaster preparedness, inadequate coverage of emergency response protocols, limited focus on crisis management, insufficient training on disaster mitigation strategies, and inadequate public health emergency preparedness

Step 8: Theme interpretation

The themes were interpreted in the context of the research question and objectives. The findings suggest that Iranian medical sciences curricula may not be adequately equipped to prepare graduates to effectively respond to incidents and disasters.

Step 9: Reporting

The results were reported in a clear and concise manner, using tables, figures, and narratives to present the findings.

Step 10: Validation

According to Guba and Lincoln [28], to enhance rigor in this study, we employed several strategies:

Credibility: We achieved credibility through prolonged engagement and member checking.

Dependability: We ensured dependability by auditing our methods and cross-checking the data.

Confirmability: The research team maintained objectivity in conducting the study and deriving unbiased findings.

Transferability: We facilitated transferability by providing detailed descriptions and conducting data collection and analysis concurrently.

Results

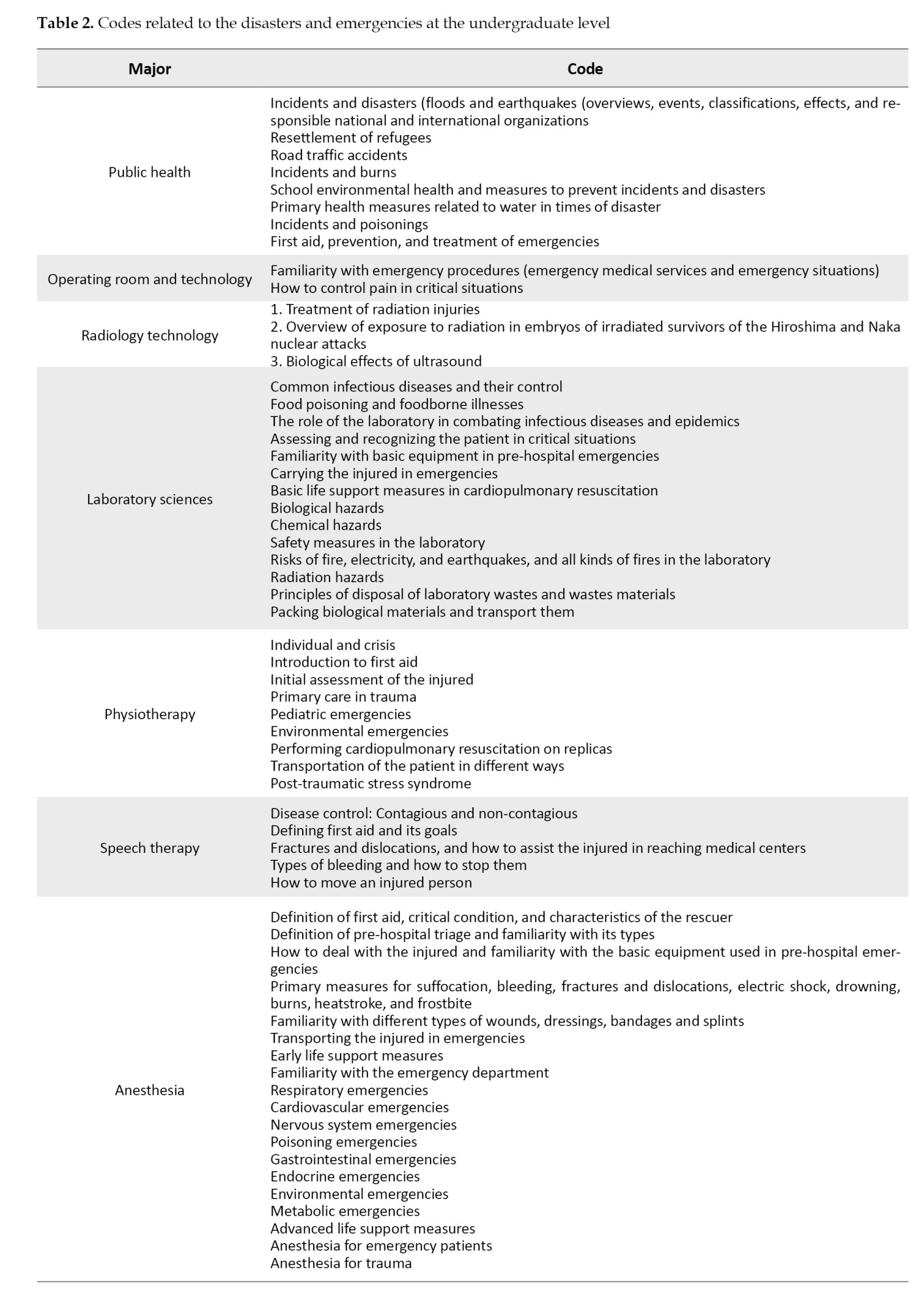

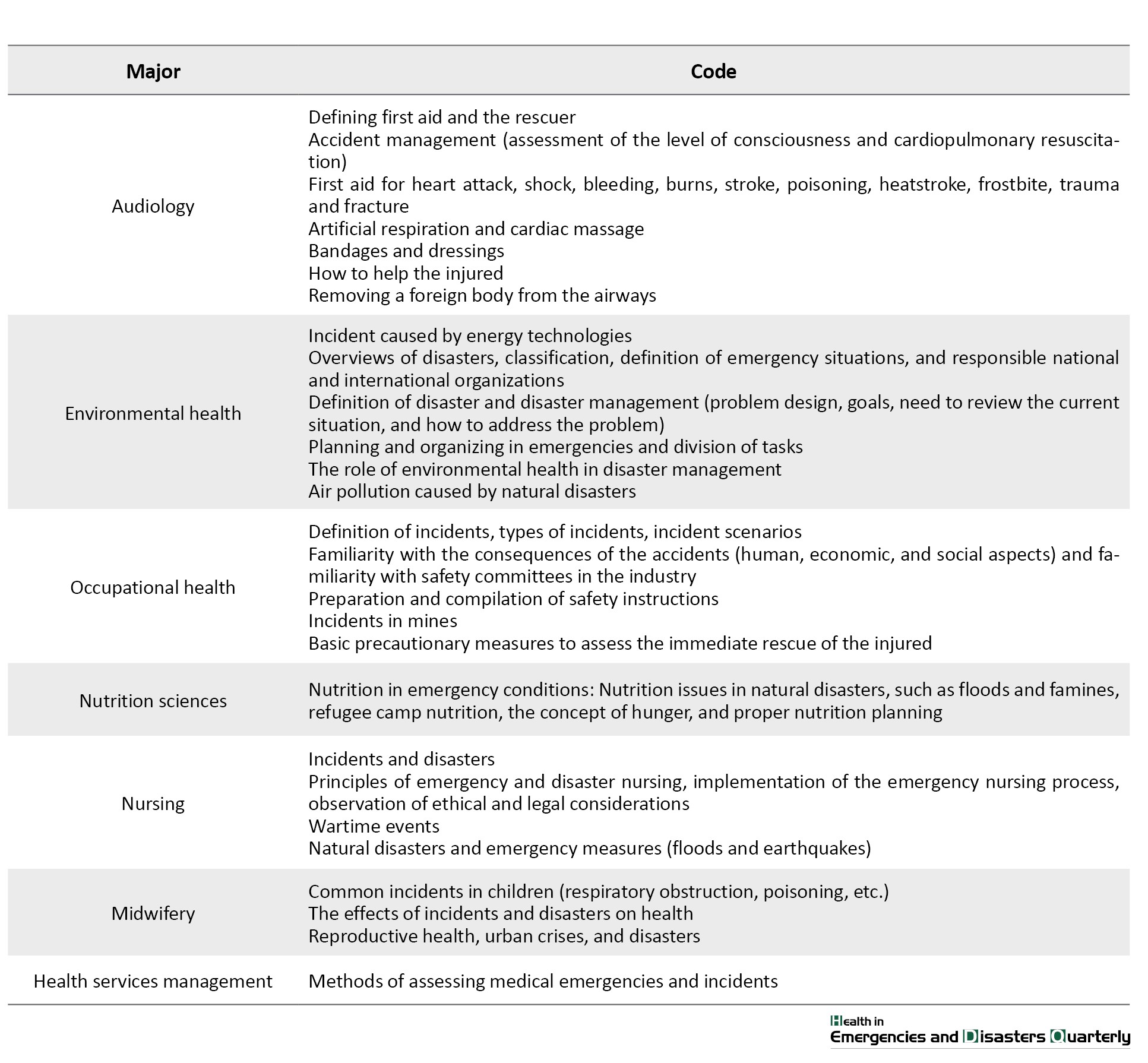

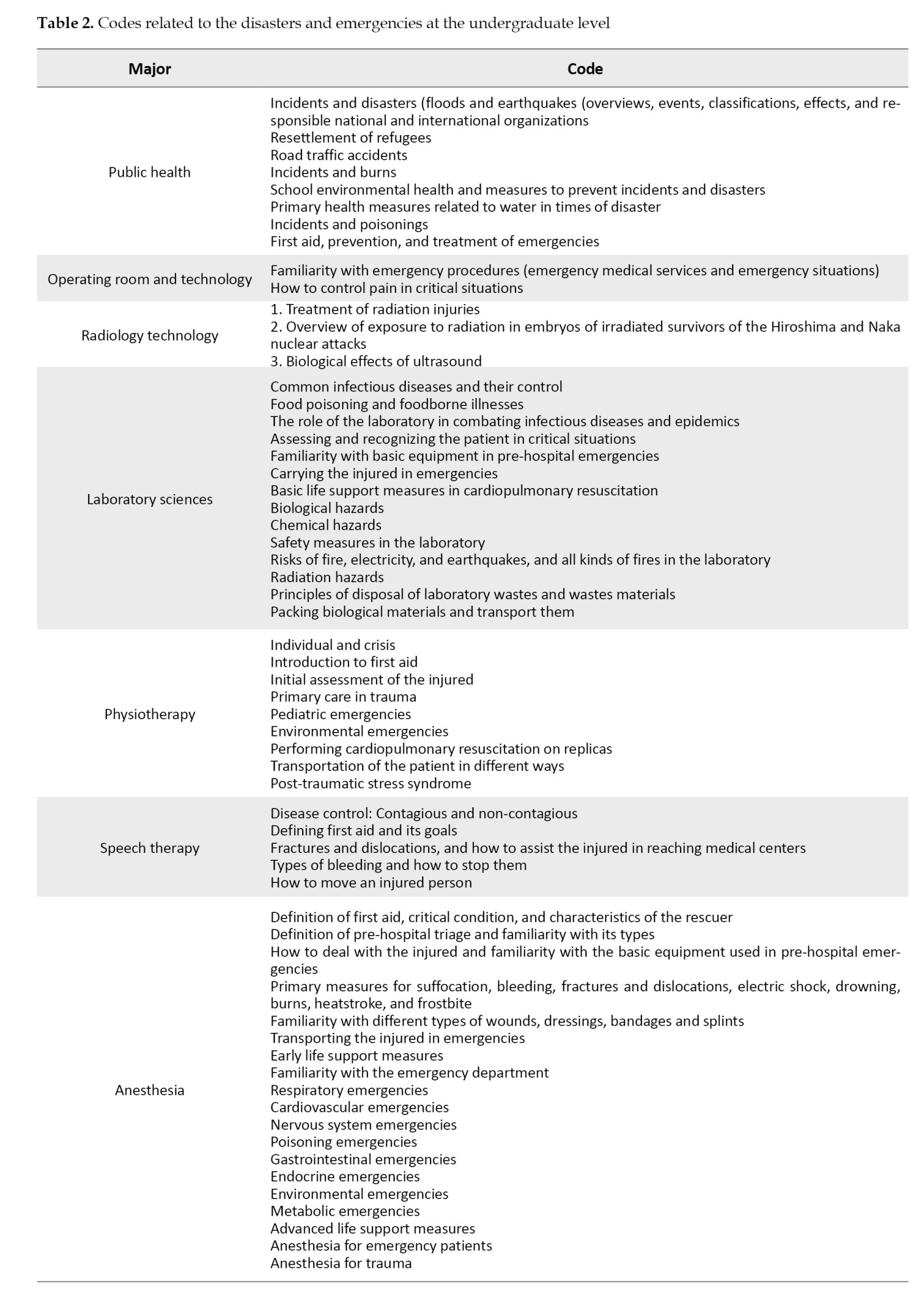

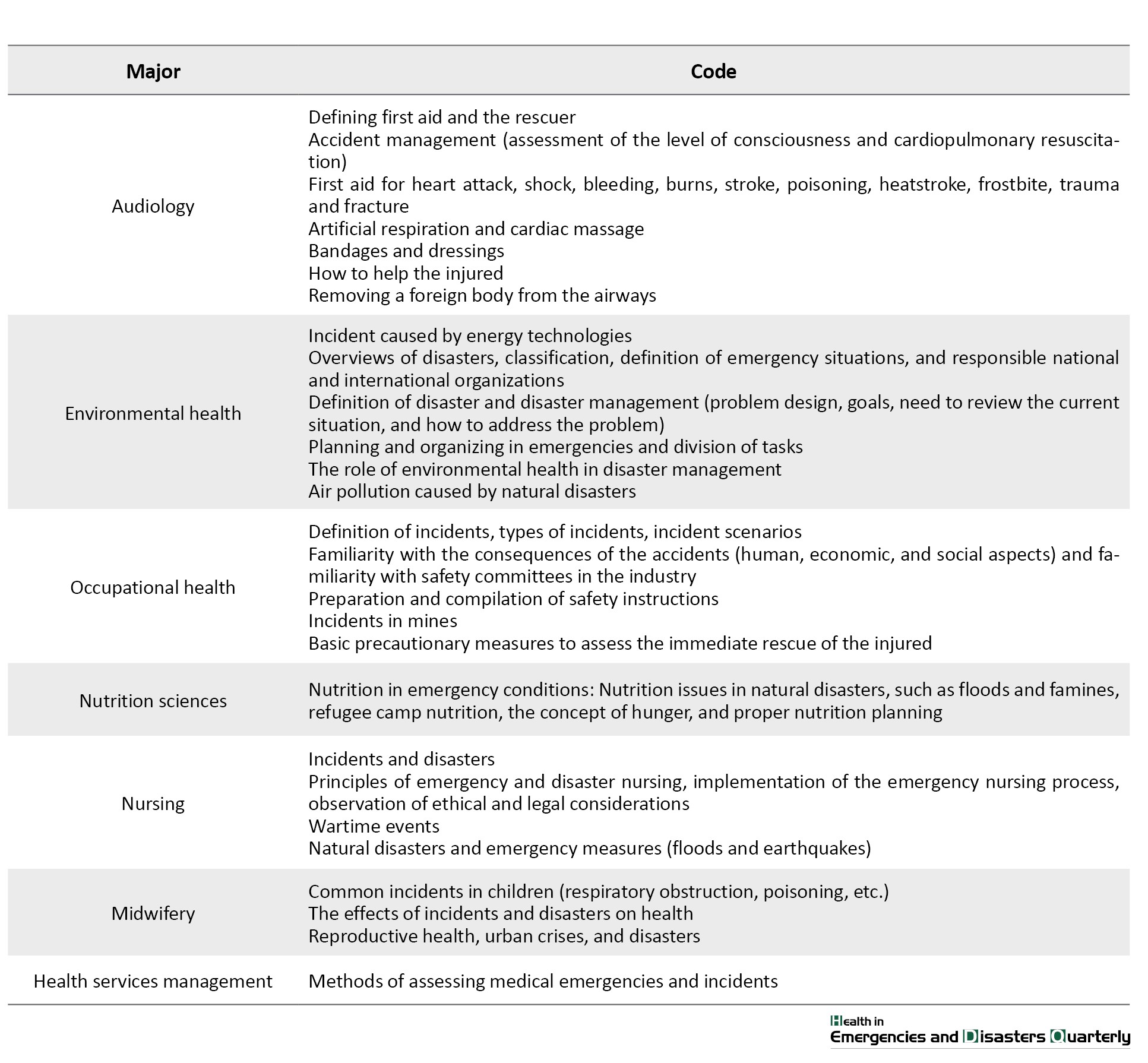

Table 2 lists the codes related to the theme of disaster and emergencies by area of study at the undergraduate level.

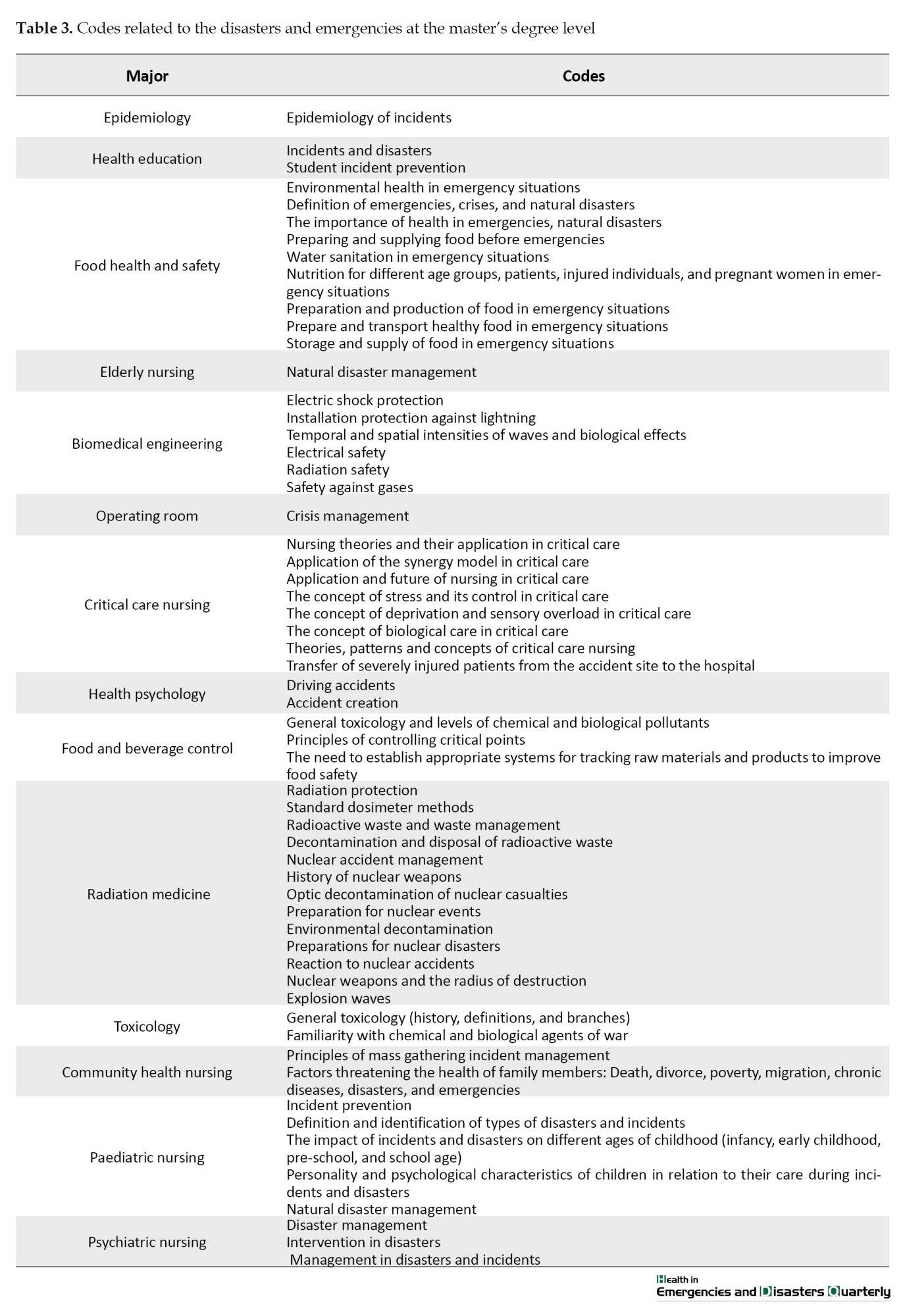

As seen in Table 3, most of the topics related to disaster and emergencies belonged to anesthesia (19 times), laboratory sciences (14 times), and public health (11 times).

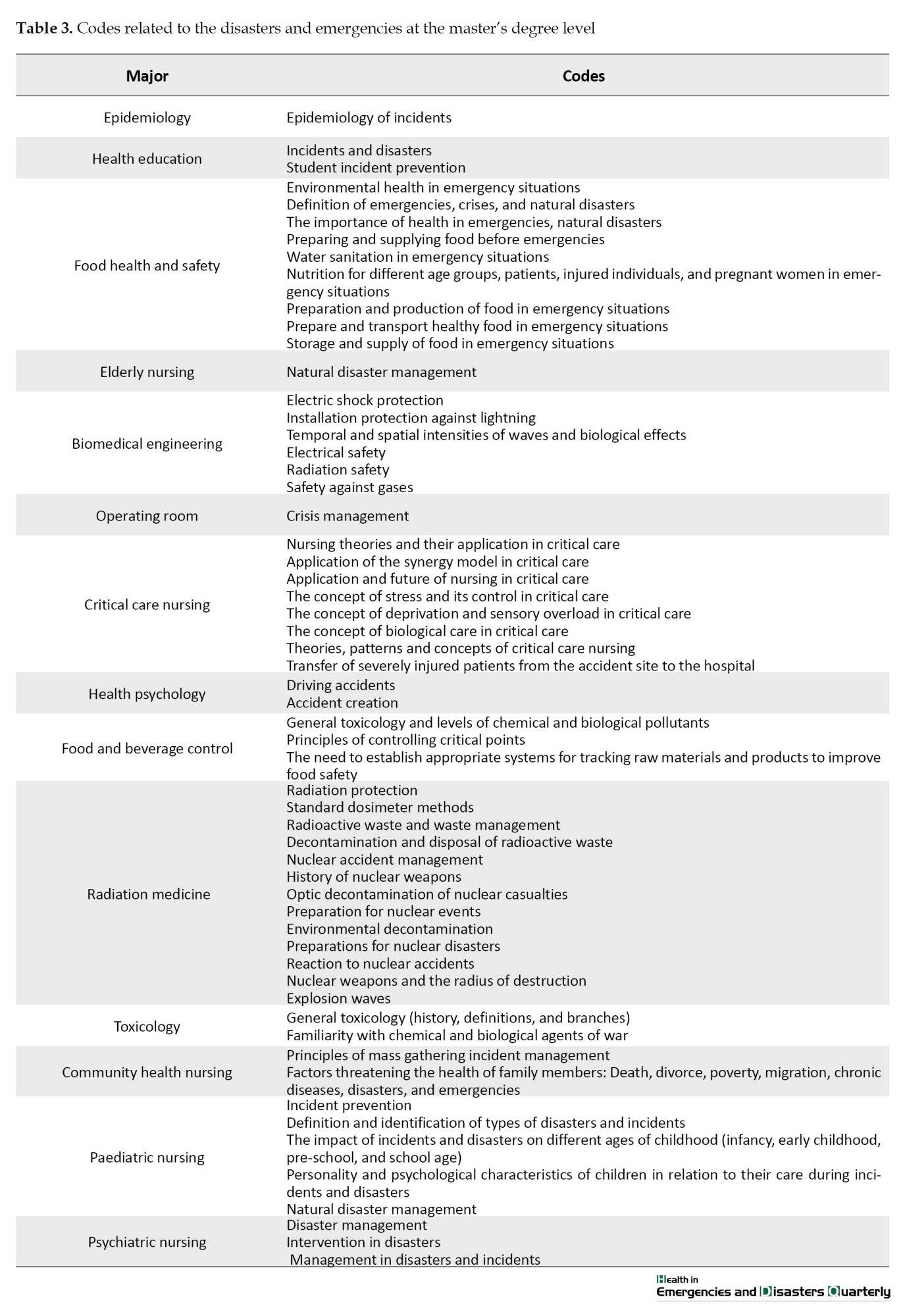

In the master’s degree, the field of radiation medicine has the most codes related to disasters and emergencies (13 times), while food health and safety is in second place (9 times). Besides, 13 majors, such as medical education, health information technology, physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, library and medical information, audiology, pharmaceutical supervision, health economics, social welfare, health sciences in nutrition, nutrition sciences, and health services management, did not have any codes in terms of disaster and emergencies.

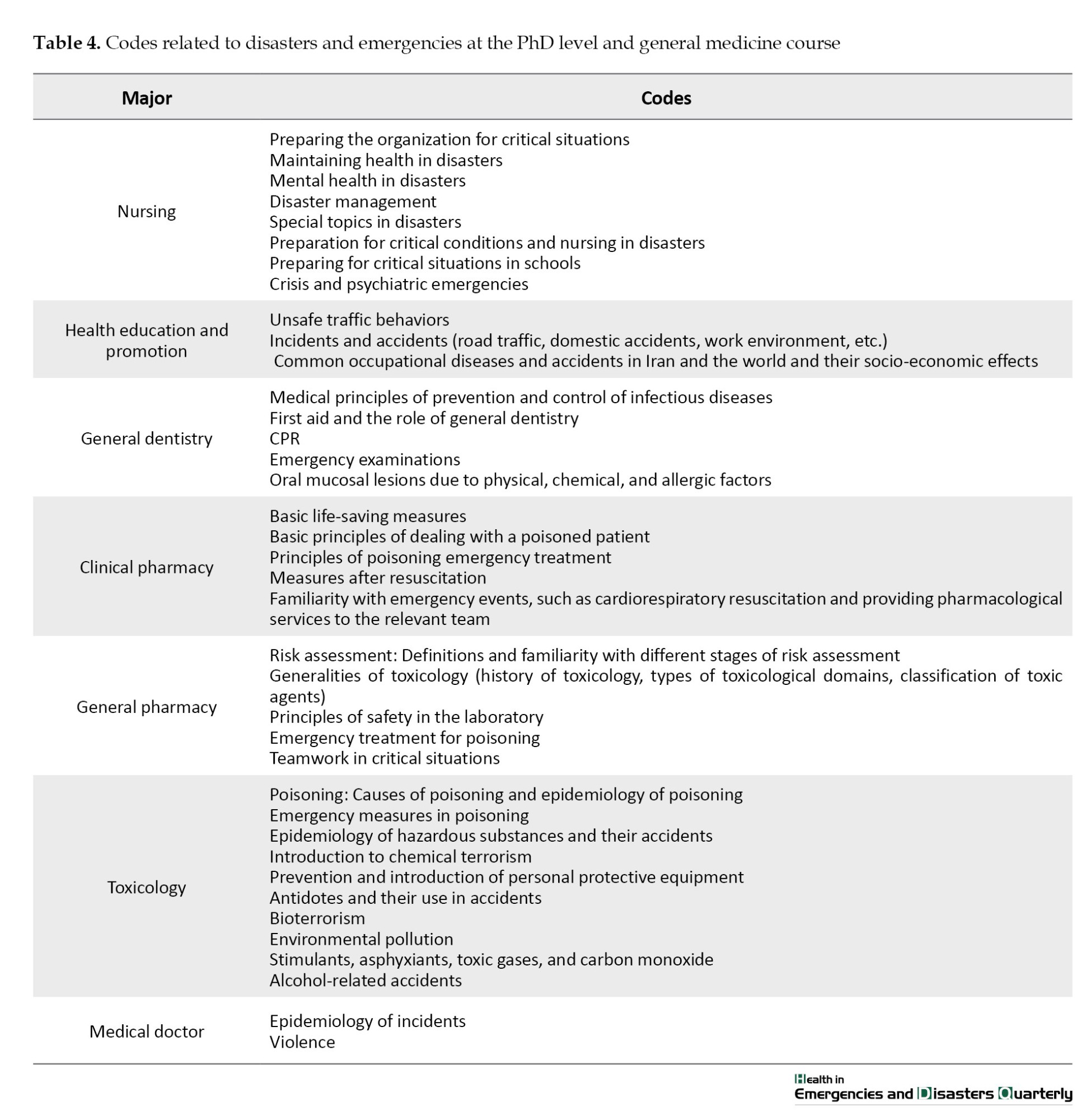

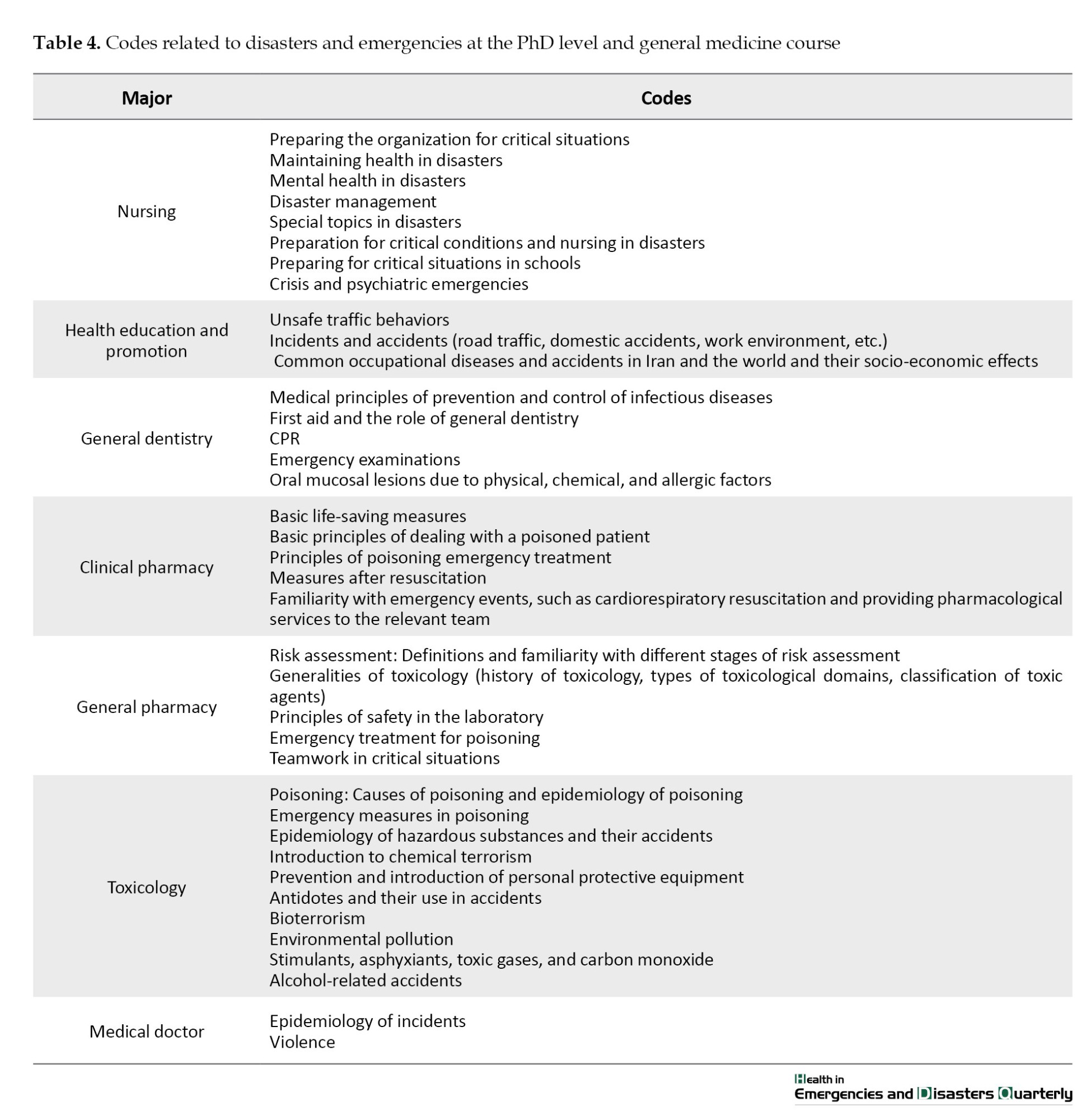

Regarding the PhD majors and medical doctor course, codes in terms of disaster and emergencies were mentioned 10 times in the field of toxicology, 8 times in nursing, and 4 times in education and community health promotion. However, there were no codes related to disasters and emergencies in the 8 majors, including nutrition sciences, health services management, orthotics and prosthetics, medical library, medical pharmacology, nuclear pharmacy, traditional pharmacy, and economics and drug management.

Discussion

Incidents and disasters, whether natural or man-made, can have devastating consequences for individuals, communities, and healthcare systems. The ability of healthcare professionals to respond effectively in these situations is critical to mitigating the impact of disasters and saving lives. Medical sciences education plays a vital role in preparing healthcare professionals to respond to incidents and disasters, yet there is growing concern that many medical sciences curricula may not be adequately equipping graduates with the necessary knowledge and skills to do so. This study aimed to address this knowledge gap by conducting a content analysis of the official curricula of undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in medical sciences in Iran, focusing on disaster response and management. In general, the findings showed that the concept of disasters and emergencies has been more expressed in the undergraduate courses of medical sciences and, in this respect, more focus has been paid to this concept in the majors of anesthesia, laboratory sciences, and public health. Notwithstanding the significance of the disasters and emergencies and their interdisciplinary nature, only 14 undergraduate courses cover topics related to this area. The findings also revealed that there are only two topics related to disasters and emergencies in the medical doctor course, but they are not technical or professional. Regarding the postgraduate and PhD degrees, nearly all majors suffer from a paucity of topics related to disasters and emergencies.

Physicians, as one of the basic pillars, have an important role in disaster management. In Iran, most emergency departments of hospitals and emergency management systems (EMS) are managed by general practitioners (GPs) or specialist assistants. On the other hand, during disasters and emergencies, they are the first line of treatment as members of the disaster medical assistance team (DMAT). However, there is insufficient instruction on the introduction of natural and man-made events, triage, and hospital and pre-hospital emergency care facilities in the general medicine and residency training programs.

The results of Kianmehr et al.’s research are in line with this research and show that there is not enough education about disasters and emergencies for physicians, both at the level of GPs and the level of specialists [25]. Adequate and continuous training for the complete preparation of physicians, in particular general practitioners, will also be useful in enhancing the quality of emergency services given to injured individuals and the management of the healthcare system in the case of disasters.

Nursing is in a better situation than the medical doctor course regarding the inclusion of disasters and emergencies, which have been addressed to varying degrees in nursing. However, the findings of Nejadshafiee et al.’s research suggest that the amount of attention paid to issues of disaster and emergencies in the current nursing curriculum is very limited. Therefore, it is important to revise undergraduate nursing courses to enhance the capacity to care for injured people during disasters and emergencies [29]. Alhani and Jalalinia further point out that there are shortcomings in educational planning and the implementation of the nursing curriculum. Nurses graduating from medical universities are not adequately prepared for disasters. Furthermore, the current preparation approaches are not adequate to prepare nurses for clinical practice in disaster situations [12].

In general, research conducted in Iran and around the world reveals that the preparedness of healthcare providers to provide healthcare in disaster circumstances is poor and requires more attention [13-16, 30-32]. However, many medical disciplines do not have enough topics related to disasters and emergencies and do not provide any training courses in this respect. Regarding dentistry, the findings of Aljarbou’s study have shown that clinical dental students have little knowledge of how to provide dental services during COVID-19 [33], despite the critical significance of biological incidents and pandemics in the context of disasters. The findings of this study showed that dentistry has limited topics related to this field.

Pharmacy faces similar conditions. The results of McCourt et al.’s systematic review regarding the level of preparedness of pharmacists and pharmacy students in disasters were consistent with those of this study [34]. Their results show that preparedness in both groups is assessed as poor to moderate, which may have negative effects on patients injured in disasters. The results of this study also indicated that, due to the importance of general pharmacy, the issues related to disasters and emergencies are insufficiently addressed.

Rehabilitation courses exhibit the same conditions. Hong and Cho show that occupational therapy students have little knowledge about the symptoms, growth mechanism, and diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and do not receive adequate training on disaster and emergencies [35]. The findings of this study also showed that occupational therapy lacks topics related to disasters and emergencies.

Safapour et al. claim that the general perception of disasters and emergencies has improved; however, there is still no consistent strategy for preparing medical sciences students [36]. Tan et al.’s research also found that just 50 percent of college students are able to rescue the injured in a disaster on the basis of their knowledge and skills [37].

The results of the current research also suggest that few topics related to disasters and emergencies have been considered in various areas of medical science. Many of the course topics are theoretical, and the design of courses does not adequately focus on enhancing students’ skills, particularly in the area of psychomotor skills related to disasters and emergencies.

Nipa et al. also point out that there is sufficient evidence of the significance of incorporating disaster-related subjects in academic disciplines [38]. However, the findings of Schilly et al.’s research demonstrate that the curriculum effectively enhanced participants’ initial perspectives on the education requirements of health professionals, their readiness to merge professional roles into emergency response systems, and confidence in assessing exposure risks and triage skills. The majority of participants had minimal recent disaster training and drill exposure. Particularly noteworthy was the consistent belief among most participants throughout the study that disaster preparedness training should be mandatory for medical licensure [39].

What is really important, however, is to adapt topics to the specialized and technical needs of the disciplines. Meanwhile, a course entitled “principles and basics of risk management of disasters and emergencies” has recently been planned and announced in Iran in 2020. This course has a common theme for all disciplines and is discussed entirely from a technical perspective. With this approach, medical sciences students who provide health care in the event of an incident will not acquire practical skills in their field of specialization. However, the functions and methods of providing care in disasters and emergencies are completely different from those in usual circumstances, and students must have sufficient knowledge and skills in this area.

Conclusion

Our research highlights a significant gap in the inclusion of topics related to disasters and emergencies across various medical sciences curricula in Iran. The findings reveal that, while certain fields, such as anesthesia, laboratory sciences, and public health, exhibit a higher frequency of relevant content, many critical areas—particularly at the master’s and doctoral levels—lack any emphasis on disaster preparedness and response. Overall, the absence of disaster and emergency topics in medical sciences majors is evident. Iran, like many other countries around the world, is facing an increasing number of disasters and emergencies. The importance of enhancing the knowledge and skills of health care professionals has become more apparent. As medical science graduates serve as healthcare providers in disasters and emergencies, it seems important to incorporate related topics into education curricula.

It is suggested that, considering the broad variety of disasters and emergencies, it is not advisable to design generic topics for all fields of medical science. Instead, it is more important to propose specialized topics tailored to the needs of each major and different educational levels in a theoretical-practical manner. This approach ensures that incident and disaster training is delivered based on specific requirements, skills, and comprehensive experiences, representing a step toward adopting responsive training.

Limitations

Limited generalizability: Given the specific focus on Iranian medical sciences curricula, the study’s findings cannot be generalizable to other countries or contexts.

Limited depth of analysis: We only conducted a content analysis of the curricula and did not explore the implementation or effectiveness of the curricula in practice.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (NASR), Tehran, Iran (Code: 960306).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (NASR), Tehran, Iran (Code: 960306).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mehdi Nosratabadi and Mostafa Amini-Rarani; Methodology: Golrokh Atighechian; Data collection and analysis: Mostafa Amini-Rarani and Golrokh Atighechian; Investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (NASR), Tehran, Iran, for their support of this study. Their commitment to advancing research in medical education has been invaluable to this work.

We live in a world with rapidly accelerating hazards, both natural and man-made [1]. Disasters impact the lives of millions around the world and disrupt the development of nations and communities [2]. Between 2010 and 2014, 1,728 natural disasters occurred in the world alone, resulting in nearly 400,000 deaths and more than 850 billion USD in costs [3]. Also, in 2023, the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) documented 399 natural hazard-related disasters that caused 86,473 deaths and impacted 93.1 million individuals. The financial damages totaled 202.7 billion USD [4]. Iran is also a vulnerable and devastating disaster-prone nation [5]. Furthermore, the frequency and severity of many climate change-related disasters are expected to rise within the coming decades due to climate change and global warming [6]. Also, as threats develop, vulnerabilities grow, and new vulnerabilities arise.

The healthcare system in Iran and many other countries around the world faced one of the most important historical challenges in 2020 as a result of the worldwide epidemic of COVID-19. This emerging pandemic challenged not only many achievements in medical and health sciences but also a large number of social and political foundations, raising serious issues [7]. In this regard, Tripathi points out that the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of enhancing awareness and preparedness, particularly among healthcare providers [8]. Saffari-darberazi et al. also showed that one of the most significant infrastructures for hospital resilience against COVID-19 was the training and enhancement of the educational abilities of healthcare providers in hospitals [9].

Therefore, in such situations, it is vital to avoid the occurrence of hazards, mitigate their effects, and handle them effectively. Preparedness with modern knowledge of the types of hazards and methods of prevention is essential for an efficient response to disasters and emergencies. People who wish to be capable of responding adequately to disasters and emergencies must be educated in this crucial area. To minimize the effects of disasters, communities should be well informed of how to respond to disasters by health practitioners, and health practitioners primarily should be well educated in disaster management [10, 11]. According to studies, disaster education is a practical, operational, and cost-effective risk management method.

On the other hand, a great deal of study has been conducted on the educational needs of healthcare professionals in the event of disasters and emergencies. Studies conducted by Alhani and Jalalinia, Zarea et al., Nekooei Moghaddam et al., Taghizadeh et al., Pesiridis et al., and Oztekin et al. also confirm the high educational needs of healthcare providers to provide disaster services [12-17]. However, the level of preparedness of healthcare providers for disasters in many countries is inadequate [18]. This is also demonstrated by research in European countries, such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy [19-21], and is even more pronounced in developing countries, such as Yemen, Saudi Arabia, China, Ethiopia, and Malaysia [21-24]. Also, similar conditions exist in Iran [25].

However, to develop a policy document on disaster management training in the health sector and to implement training tasks in the field of disaster management law in Iran, plans are underway to create a course on “disaster risk reduction and preparedness” in the form of two compulsory courses for all medical science disciplines [26]. Developing a subject specific to the requirements of society and providing responsive education for this course primarily requires an analysis of current medical science curricula, focusing on the role of the concept of disaster. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the content of the official medical science curriculum from the perspective of disaster and emergencies.

Materials and Methods

In this qualitative content analysis study, the content of the official curricula of undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) of Iran was explored from a disasters and emergencies point of view. We considered each educational curriculum as a unit of analysis.

Screening

All undergraduate and postgraduate disciplines (320 courses) at MOHME of Iran were identified (Table 1).

The curricula of the disciplines were then screened based on the main concepts of disaster, incident, emergency, and disaster management. Consequently, disciplines unrelated to these concepts were excluded based on face validity (n=285). Finally, the remaining disciplines (n=35) were carefully reviewed and analyzed.

Qualitative content analysis

The conventional (inductive) content analysis approach [27] was used to analyze the content of curricula. Conventional (inductive) content analysis is a research methodology used to analyze and interpret the meaning of textual data. It is an inductive qualitative content analysis that involves a systematic and objective examination of the content to identify patterns, themes, and meanings. Here are the steps involved in the conventional content analysis approach:

Step 1: Research objectives

The objectives of this research were:

To analyze the content of Iranian medical sciences curricula;

To identify the extent to which the curricula address disaster response and management.

Step 2: Data collection

The researchers collected the medical sciences curricula from Offices of the Council for Medical, Pharmacy, Dentistry, Basic Sciences, Health, and Specialized Education on the Iranian MOHME website, which served as the data for the study.

Step 3: Data preparation

The curricula were reviewed, and relevant sections related to disaster response and management were extracted and organized for analysis.

Step 4: Coding

A coding scheme was developed to identify themes and concepts related to disaster response and management, such as: Disaster preparedness, emergency response, crisis management, disaster mitigation, and Public health emergency preparedness.

Step 5: Coding application

The coding scheme was applied to the extracted curriculum content, and codes were assigned to relevant segments of the text.

Step 6: Data analysis

The coded data were analyzed to identify patterns, themes, and relationships between the codes. The frequency, intensity, and context of the codes were examined to determine the emphasis placed on disaster response and management in the curricula.

Step 7: Theme identification

Themes emerged from the data analysis, such as: Lack of emphasis on disaster preparedness, inadequate coverage of emergency response protocols, limited focus on crisis management, insufficient training on disaster mitigation strategies, and inadequate public health emergency preparedness

Step 8: Theme interpretation

The themes were interpreted in the context of the research question and objectives. The findings suggest that Iranian medical sciences curricula may not be adequately equipped to prepare graduates to effectively respond to incidents and disasters.

Step 9: Reporting

The results were reported in a clear and concise manner, using tables, figures, and narratives to present the findings.

Step 10: Validation

According to Guba and Lincoln [28], to enhance rigor in this study, we employed several strategies:

Credibility: We achieved credibility through prolonged engagement and member checking.

Dependability: We ensured dependability by auditing our methods and cross-checking the data.

Confirmability: The research team maintained objectivity in conducting the study and deriving unbiased findings.

Transferability: We facilitated transferability by providing detailed descriptions and conducting data collection and analysis concurrently.

Results

Table 2 lists the codes related to the theme of disaster and emergencies by area of study at the undergraduate level.

As seen in Table 3, most of the topics related to disaster and emergencies belonged to anesthesia (19 times), laboratory sciences (14 times), and public health (11 times).

In the master’s degree, the field of radiation medicine has the most codes related to disasters and emergencies (13 times), while food health and safety is in second place (9 times). Besides, 13 majors, such as medical education, health information technology, physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, library and medical information, audiology, pharmaceutical supervision, health economics, social welfare, health sciences in nutrition, nutrition sciences, and health services management, did not have any codes in terms of disaster and emergencies.

Regarding the PhD majors and medical doctor course, codes in terms of disaster and emergencies were mentioned 10 times in the field of toxicology, 8 times in nursing, and 4 times in education and community health promotion. However, there were no codes related to disasters and emergencies in the 8 majors, including nutrition sciences, health services management, orthotics and prosthetics, medical library, medical pharmacology, nuclear pharmacy, traditional pharmacy, and economics and drug management.

Discussion

Incidents and disasters, whether natural or man-made, can have devastating consequences for individuals, communities, and healthcare systems. The ability of healthcare professionals to respond effectively in these situations is critical to mitigating the impact of disasters and saving lives. Medical sciences education plays a vital role in preparing healthcare professionals to respond to incidents and disasters, yet there is growing concern that many medical sciences curricula may not be adequately equipping graduates with the necessary knowledge and skills to do so. This study aimed to address this knowledge gap by conducting a content analysis of the official curricula of undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in medical sciences in Iran, focusing on disaster response and management. In general, the findings showed that the concept of disasters and emergencies has been more expressed in the undergraduate courses of medical sciences and, in this respect, more focus has been paid to this concept in the majors of anesthesia, laboratory sciences, and public health. Notwithstanding the significance of the disasters and emergencies and their interdisciplinary nature, only 14 undergraduate courses cover topics related to this area. The findings also revealed that there are only two topics related to disasters and emergencies in the medical doctor course, but they are not technical or professional. Regarding the postgraduate and PhD degrees, nearly all majors suffer from a paucity of topics related to disasters and emergencies.

Physicians, as one of the basic pillars, have an important role in disaster management. In Iran, most emergency departments of hospitals and emergency management systems (EMS) are managed by general practitioners (GPs) or specialist assistants. On the other hand, during disasters and emergencies, they are the first line of treatment as members of the disaster medical assistance team (DMAT). However, there is insufficient instruction on the introduction of natural and man-made events, triage, and hospital and pre-hospital emergency care facilities in the general medicine and residency training programs.

The results of Kianmehr et al.’s research are in line with this research and show that there is not enough education about disasters and emergencies for physicians, both at the level of GPs and the level of specialists [25]. Adequate and continuous training for the complete preparation of physicians, in particular general practitioners, will also be useful in enhancing the quality of emergency services given to injured individuals and the management of the healthcare system in the case of disasters.

Nursing is in a better situation than the medical doctor course regarding the inclusion of disasters and emergencies, which have been addressed to varying degrees in nursing. However, the findings of Nejadshafiee et al.’s research suggest that the amount of attention paid to issues of disaster and emergencies in the current nursing curriculum is very limited. Therefore, it is important to revise undergraduate nursing courses to enhance the capacity to care for injured people during disasters and emergencies [29]. Alhani and Jalalinia further point out that there are shortcomings in educational planning and the implementation of the nursing curriculum. Nurses graduating from medical universities are not adequately prepared for disasters. Furthermore, the current preparation approaches are not adequate to prepare nurses for clinical practice in disaster situations [12].

In general, research conducted in Iran and around the world reveals that the preparedness of healthcare providers to provide healthcare in disaster circumstances is poor and requires more attention [13-16, 30-32]. However, many medical disciplines do not have enough topics related to disasters and emergencies and do not provide any training courses in this respect. Regarding dentistry, the findings of Aljarbou’s study have shown that clinical dental students have little knowledge of how to provide dental services during COVID-19 [33], despite the critical significance of biological incidents and pandemics in the context of disasters. The findings of this study showed that dentistry has limited topics related to this field.

Pharmacy faces similar conditions. The results of McCourt et al.’s systematic review regarding the level of preparedness of pharmacists and pharmacy students in disasters were consistent with those of this study [34]. Their results show that preparedness in both groups is assessed as poor to moderate, which may have negative effects on patients injured in disasters. The results of this study also indicated that, due to the importance of general pharmacy, the issues related to disasters and emergencies are insufficiently addressed.

Rehabilitation courses exhibit the same conditions. Hong and Cho show that occupational therapy students have little knowledge about the symptoms, growth mechanism, and diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and do not receive adequate training on disaster and emergencies [35]. The findings of this study also showed that occupational therapy lacks topics related to disasters and emergencies.

Safapour et al. claim that the general perception of disasters and emergencies has improved; however, there is still no consistent strategy for preparing medical sciences students [36]. Tan et al.’s research also found that just 50 percent of college students are able to rescue the injured in a disaster on the basis of their knowledge and skills [37].

The results of the current research also suggest that few topics related to disasters and emergencies have been considered in various areas of medical science. Many of the course topics are theoretical, and the design of courses does not adequately focus on enhancing students’ skills, particularly in the area of psychomotor skills related to disasters and emergencies.

Nipa et al. also point out that there is sufficient evidence of the significance of incorporating disaster-related subjects in academic disciplines [38]. However, the findings of Schilly et al.’s research demonstrate that the curriculum effectively enhanced participants’ initial perspectives on the education requirements of health professionals, their readiness to merge professional roles into emergency response systems, and confidence in assessing exposure risks and triage skills. The majority of participants had minimal recent disaster training and drill exposure. Particularly noteworthy was the consistent belief among most participants throughout the study that disaster preparedness training should be mandatory for medical licensure [39].

What is really important, however, is to adapt topics to the specialized and technical needs of the disciplines. Meanwhile, a course entitled “principles and basics of risk management of disasters and emergencies” has recently been planned and announced in Iran in 2020. This course has a common theme for all disciplines and is discussed entirely from a technical perspective. With this approach, medical sciences students who provide health care in the event of an incident will not acquire practical skills in their field of specialization. However, the functions and methods of providing care in disasters and emergencies are completely different from those in usual circumstances, and students must have sufficient knowledge and skills in this area.

Conclusion

Our research highlights a significant gap in the inclusion of topics related to disasters and emergencies across various medical sciences curricula in Iran. The findings reveal that, while certain fields, such as anesthesia, laboratory sciences, and public health, exhibit a higher frequency of relevant content, many critical areas—particularly at the master’s and doctoral levels—lack any emphasis on disaster preparedness and response. Overall, the absence of disaster and emergency topics in medical sciences majors is evident. Iran, like many other countries around the world, is facing an increasing number of disasters and emergencies. The importance of enhancing the knowledge and skills of health care professionals has become more apparent. As medical science graduates serve as healthcare providers in disasters and emergencies, it seems important to incorporate related topics into education curricula.

It is suggested that, considering the broad variety of disasters and emergencies, it is not advisable to design generic topics for all fields of medical science. Instead, it is more important to propose specialized topics tailored to the needs of each major and different educational levels in a theoretical-practical manner. This approach ensures that incident and disaster training is delivered based on specific requirements, skills, and comprehensive experiences, representing a step toward adopting responsive training.

Limitations

Limited generalizability: Given the specific focus on Iranian medical sciences curricula, the study’s findings cannot be generalizable to other countries or contexts.

Limited depth of analysis: We only conducted a content analysis of the curricula and did not explore the implementation or effectiveness of the curricula in practice.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (NASR), Tehran, Iran (Code: 960306).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (NASR), Tehran, Iran (Code: 960306).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mehdi Nosratabadi and Mostafa Amini-Rarani; Methodology: Golrokh Atighechian; Data collection and analysis: Mostafa Amini-Rarani and Golrokh Atighechian; Investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education (NASR), Tehran, Iran, for their support of this study. Their commitment to advancing research in medical education has been invaluable to this work.

References

- Otoufi M, Sharififar S, Pishgooie A, Habibi H. [Disasters characteristics; an effective factor in risk perception of healthcare middle managers in armed forces: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Military Caring Sciences. 2019; 6(3):215-27. [DOI:10.29252/mcs.6.3.7]

- Poursoleyman L, Aliyari SH, Sharififar ST, Pishgooie SAH. [Development of instructional curriculum of maternal and newborn care for army health providers in disasters (Persian)]. Military Caring Sciences. 2018; 5(1):1-12. [DOI:10.29252/mcs.5.1.1]

- Tanner A, Doberstein B. Emergency preparedness amongst university students. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2015; 13: 409-13. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.08.007]

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). Disaster in numbers. Brussels: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters; 2023. [Link]

- Fekete A, Asadzadeh A, Ghafory-Ashtiany M, Amini-Hosseini K, Hetkämper Ch, Moghadas M, et al. Pathways for advancing integrative disaster risk and resilience management in Iran: Needs, challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2020; 49:101635.[DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101635]

- Mousavi A, Ardalan A, Takian A, Ostadtaghizadeh A, Naddafi K, Bavani AM. Climate change and health in Iran: A narrative review. Journal of Environmental Health Science & Engineering. 2020; 18(1):367-78. [DOI:10.1007/s40201-020-00462-3] [PMID]

- Heidari M. The necessity of knowledge management in novel coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis. Depiction of Health. 2020; 11(2):94-7. [DOI:10.34172/doh.2020.10]

- Tripathi R, Alqahtani SS, Albarraq AA, Meraya AM, Tripathi P, Banji D, Alshahrani S, et al. Awareness and preparedness of covid-19 outbreak among healthcare workers and other residents of South-West Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional survey. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020; 8:482. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00482] [PMID]

- Saffari-Darberazi A, Malekinejad P, Ziaeian M, Ajdari A. [Designing a comprehensive model of hospital resilience in the face of COVID-19 disease (Persian)]. Journal of Health Administration. 2020; 32(2):76-88. [DOI:10.29252/jha.23.2.76]

- Alrazeeni D. Saudi EMS students’ perception of and attitudes toward their preparedness for disaster management. Journal of Education and Practice. 2015; 6(35):110-6. [Link]

- Li T, Wang Q, Xie Z. Disaster response knowledge and its social determinants: A cross-sectional study in Beijing, China. Plos One. 2019; 14(3):e0214367. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0214367] [PMID]

- Jalalinia F, Alhani F. [Pathology of training the course on emergency, and crisis management in nursing curriculum: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2011; 11(3):254-68. [Link]

- Zarea K, Beiranvand S, Sheini-Jaberi P, Nikbakht-Nasrabadi A. Disaster nursing in Iran: Challenges and opportunities. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2014; 17(4):190-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.aenj.2014.05.006] [PMID]

- Nekooei Moghaddam M, Saeed S, Khanjani N, Arab M. Nurses' requirements for relief and casualty support in disasters: A qualitative study. Nursing and Midwifery Studies. 2014; 3(1):e9939. [DOI:10.17795/nmsjournal9939] [PMID]

- Taghizadeh Z, Montazeri A, Khoshnamrad M. Educational needs of midwifery students regarding mother and infant mortality prevention services in critical situation. Hayat. 2015; 21(2):54- 66. [Link]

- Pesiridis T, Sourtzi P, Galanis P, Kalokairinou A. Development, implementation and evaluation of a disaster training programme for nurses: A switching replications randomized controlled trial. Nurse Education in Practice. 2015; 15(1):63-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2014.02.001] [PMID]

- Oztekin SD, Larson EE, Altun Ugras G, Yuksel S. Educational needs concerning disaster preparedness and response: A comparison of undergraduate nursing students from Istanbul, Turkey, and Miyazaki, Japan. Japan Journal of Nursing Science. 2014; 11(2):94-101. [DOI:10.1111/jjns.12008] [PMID]

- Gillani AH, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, Akbar J, Fang Y. Evaluation of disaster medicine preparedness among healthcare profession students: A cross-sectional study in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):2027. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17062027] [PMID]

- Wunderlich R, Ragazzoni L, Ingrassia PL, Corte FD, Grundgeiger J, Bickelmayer JW, et al. Self-perception of medical students' knowledge and interest in disaster medicine: Nine years after the approval of the curriculum in German universities. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2017; 32(4):374-81. [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X17000280] [PMID]

- Ragazzoni L, Ingrassia PL, Gugliotta G, Tengattini M, Franc JM, Corte FD. Italian medical students and disaster medicine: Awareness and formative needs. American Journal of Disaster Medicine. 2013; 8(2):127-36. [DOI:10.5055/ajdm.2013.0119] [PMID]

- Mortelmans LJ, Bouman SJ, Gaakeer MI, Dieltiens G, Anseeuw K, Sabbe MB. Dutch senior medical students and disaster medicine: A national survey. International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2015; 8(1):77. [DOI:10.1186/s12245-015-0077-0] [PMID]

- Berhanu N, Abrha H, Ejigu Y, Woldemichael K. Knowledge, experiences and training needs of health professionals about disaster preparedness and response in Southwest Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences. 2016; 26(5):415-26. [DOI:10.4314/ejhs.v26i5.3] [PMID]

- Ahayalimudin N, Osman NN. Disaster management: Emergency nursing and medical personnel's knowledge, attitude and practices of the east coast region hospitals of Malaysia. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal. 2016; 19(4):203-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.aenj.2016.08.001] [PMID]

- Nofal A, Alfayyad I, Khan A, Al Aseri Z, Abu-Shaheen A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of emergency department staff towards disaster and emergency preparedness at tertiary health care hospital in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2018; 39(11):1123-9. [DOI:10.15537/smj.2018.11.23026] [PMID]

- Kianmehr N, Mofidi M, Nejati A. [Evaluation of physicians’ knowledge of unexpected events (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of the Medical System Organization of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2009; 27(2):189-4. [Link]

- Mehr News Agency. [Compilation of the course “Preparedness for Disasters” for all majors and grades of medical sciences (Persian)] [Internet]. 2021 [Updated 7 September 2021]. Available from: [Link]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15(9):1277-88. [DOI:10.1177/1049732305276687] [PMID]

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS, Denzin NK. Handbook of qualitative research. Califónia: Sage; 1994. [Link]

- Nejadshafiee M, Sarhangi F, Rahmani A, Salari M.M. Necessity for learning the knowledge and skills required for nurses in disaster. Education Strategies in Medical Sciences. 2016; 9(5):328-34. [Link]

- Castillo MS, Corsino MA, Calibo AP, Zeck W, Capili DS, Andrade LC, et al. Turning disaster into an opportunity for quality improvement in essential intrapartum and newborn care services in the Philippines: Pre- to Posttraining assessments. BioMed Research International. 2016; 2016:6264249.[DOI:10.1155/2016/6264249] [PMID]

- Alim S, Kawabata M, Nakazawa M. Evaluation of disaster preparedness training and disaster drill for nursing students. Nurse Education Today. 2015; 35(1):25-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2014.04.016] [PMID]

- Al-Ziftawi NH, Elamin FM, Mohamed Ibrahim MI. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to practice regarding disaster medicine and preparedness among university health students. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2021; 15(3):316-24. [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2019.157] [PMID]

- Aljarbou FA, Bukhary SM, Althemery AU, Alqedairi AS. Clinical dental students' knowledge regarding proper dental settings for treating patient during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2021; 37(2):503-9. [DOI:10.12669/pjms.37.2.3768] [PMID]

- McCourt E, Singleton J, Tippett V, Nissen L. Disaster preparedness amongst pharmacists and pharmacy students: A systematic literature review. The International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2021; 29(1):12-20. [DOI:10.1111/ijpp.12669] [PMID]

- Hong Young-Ho, Cho SB. Awareness of disaster and post traumatic stress disorder in occupational therapy students. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial cooperation Society. 2017; 18(7):539-47. [Link]

- Safapour E, Kermanshachi S. Investigation of the challenges and their best practices for post-disaster reconstruction safety: Educational approach for construction hazards. Paper presented at: 99th Transportation Research Board Conference. January 12–16, 2020; Washington, DC, USA. [Link]

- Tan Y, Liao X, Su H, Li C, Xiang J, Dong Z. Disaster preparedness among university students in Guangzhou, China: Assessment of status and demand for disaster education. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2017; 11(3):310-7. [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2016.124] [PMID]

- Nipa TJ, Kermanshachi Sh, Patel R, Tafazzoli MS. Disaster preparedness education: construction curriculum requirements to increase students’ preparedness in pre- and post-disaster activities. Associated Schools of Construction Proceedings of the 56th Annual International Conference. 2020; 1:142-51. [Link]

- Schilly K, Huhn M, Visker JD, Cox C. Evaluation of a disaster preparedness curriculum and medical students' views on preparedness education requirements for health professionals. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2024; 18:e8. [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2023.230] [PMID]

Type of article: Research |

Subject:

Qualitative

Received: 2024/06/8 | Accepted: 2025/02/15 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2024/06/8 | Accepted: 2025/02/15 | Published: 2025/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |