Volume 10, Issue 4 (Summer 2025)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025, 10(4): 259-270 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hamidi Razey S, Alipour F, Mardani M, Ostadhashemi L, Sabzi Khoshnami M, Elyasi F. Exploring the Individual, Family and Social Experiences of Patients With Multiple Sclerosis During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025; 10 (4) :259-270

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-633-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-633-en.html

Soraya Hamidi Razey1

, Fardin Alipour *2

, Fardin Alipour *2

, Mostafa Mardani3

, Mostafa Mardani3

, Leila Ostadhashemi3

, Leila Ostadhashemi3

, Mohammad Sabzi Khoshnami3

, Mohammad Sabzi Khoshnami3

, Foroogh Elyasi4

, Foroogh Elyasi4

, Fardin Alipour *2

, Fardin Alipour *2

, Mostafa Mardani3

, Mostafa Mardani3

, Leila Ostadhashemi3

, Leila Ostadhashemi3

, Mohammad Sabzi Khoshnami3

, Mohammad Sabzi Khoshnami3

, Foroogh Elyasi4

, Foroogh Elyasi4

1- Student Research Committee, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Social Welfare Management Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,barbodalipour@gmail.com

3- Department of Social Work, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- MS Tavanmandsazi Charity Institute, Tehran, Iran.

2- Social Welfare Management Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Social Work, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- MS Tavanmandsazi Charity Institute, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Multiple sclerosis (MS), Individual experiences, Family experiences, Social experiences, Content analysis

Full-Text [PDF 523 kb]

(695 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3344 Views)

Full-Text: (427 Views)

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system that disrupts the myelin sheath, resulting in physical impairments and associated mental health challenges [1]. Typically manifesting between the ages of 20 and 40, MS affects women at twice the rate of men. Key symptoms include weakness, fatigue, sensory-motor nerve dysfunction, and cognitive or mood disturbances [2]. With a relatively higher prevalence among chronic neurological conditions, MS requires management focused on maintenance and patient care due to its progressive and incurable nature [3]. Globally, the prevalence of MS was estimated at 35.9 per 100000 in 2020, marking a significant increase since 2013 [4]. In Iran, the prevalence is notably higher, at approximately 100 per 100000, designating it as a high-prevalence region [5-9]. Rates vary significantly by area in Iran, with Tehran Province reporting the highest prevalence and provinces like Khuzestan and Sistan-Baluchestan the lowest [10]. Notably, the prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran continue to rise [10], surpassing those in some neighboring Middle Eastern countries [9].

Emerged in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, the COVID-19 pandemic rapidly became a global health crisis, impacting personal, familial and psychological well-being through social distancing and travel restrictions [11]. Among vulnerable populations, MS patients faced unique challenges related to lifestyle, health and treatment despite MS itself not increasing COVID-19 mortality risk [12, 13]. Patients undergoing disease-modifying therapies were particularly vulnerable to infections and heightened emotional disorders, including anxiety, stress, anger, and stigma, exacerbated by quarantine and uncertainty [14, 15]. Depression and anxiety, common among MS patients, further diminished their quality of life and treatment adherence [16]. While MS patients’ infection and mortality rates from COVID-19 were similar to the general population (3-6%), their hospitalization rates were significantly higher [17-19]. Fatigue, a prevalent and debilitating symptom in approximately 80% of MS patients [3] and heightened sensitivity to stressors, which may trigger relapses [16], added to their burden [20]. Addressing the pandemic’s less visible psychological and stress-related impacts could mitigate disease severity and recurrence [20].

Most international researchers have descriptively examined the personal and psychological effects of the coronavirus pandemic on MS patients [21-23]. In some cases, they have also addressed its social and occupational consequences [24, 25]. Domestic studies, on the other hand, have primarily focused on the psychological effects of the pandemic on MS patients [6, 20] or have investigated the psychological impact of MS in non-crisis periods before the COVID-19 pandemic [26, 27]. It is also important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with a new wave of international economic sanctions against Iran, creating unique challenges for chronic patients, including those with MS, which appear to have affected their care and health [28-30].

Existing studies emphasize the need further to explore MS patients’ experiences during epidemics like COVID-19 to inform therapeutic approaches and theoretical models. Comprehensive research can deepen understanding of these patients’ unique needs, fostering advancements in the field. This study aims to holistically examine shared human experiences by synthesizing qualitative findings, offering insights to shape services and interventions for rehabilitating MS patients during epidemics. By reviewing past experiences, the research seeks to identify gaps, analyze key issues, and determine necessary services and measures to address the multifaceted impacts of epidemics on MS patients.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative research employs a methodology grounded in the philosophy of naturalism, focusing on studying a natural phenomenon—the COVID-19 pandemic—through a holistic perspective. The patients’ experiences were examined holistically, considering their environment, context, values, daily perceptions, personal biographies, and factors related to these patients. Given the lack of sufficient theoretical resources, the analysis was conducted using a contract content analysis model based on Lundman and Granheim’s approach [31], which enabled a deep and systematic identification of the individual, familial, and social experiences of people with MS during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research was conducted in Ardabil and the participants included 24 individuals: 17 MS patients aged at least 18 years and 7 experts with significant experience working with MS patients. Participants were selected through purposive sampling, guided by specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, and employing a maximum diversity approach. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: Participants must be over 18 years old, have a minimum disease duration of one year, and provide written informed consent to participate. The exclusion criteria included the presence of cognitive disorders, mental health issues requiring treatment for three months or less and unwillingness to participate in the study. Additionally, specialists in the study must have at least three years of experience working with MS patients. The selection of participants continued until data saturation was reached. Research data were collected through semi-structured interviews between the winter of 2022 and the summer of 2022, following the necessary permissions and adherence to general ethical guidelines and specific ethical codes pertaining to vulnerable groups in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Some of these general ethical guidelines included providing special protection for participating patients, informing participants about the purpose of the research, obtaining informed consent, and ensuring professional confidentiality.

Given the special circumstances surrounding the coronavirus in the country and in accordance with the regulations set by the Corona Management Headquarters, most interviews were conducted when there were no commuting restrictions in the city. During the peak of the pandemic restrictions, some interviews were held online through social networks. The timing and location of the interviews were arranged to accommodate the participants’ convenience while adhering to health protocols specified by the Corona Management Headquarters, such as using air conditioning, wearing masks, and maintaining a safe distance. The interviews ranged from 30 to 80 minutes, depending on the patient’s condition, willingness to engage in conversation, and the nature and extent of their experiences.

Moreover, with a commitment to safeguarding confidentiality in handling information and interviews, all participants were assured that only the researcher would have access to these materials. In addition, confidentiality principles were followed, and participants were assured of privacy. Detailed explanations of the study’s protocols were provided to them, accompanied by written informed consent for their review and signature. Informed consent was obtained from all participants to record the interviews. To build rapport and ease participants into the process, the initial questions were open-ended and interpretative, such as: “How many years have you been living with MS?” and “Could you describe the first few days after your diagnosis?” As trust was established and participants became more comfortable, more specific questions followed, such as: “How did the coronavirus pandemic begin for you?” Or “how did the pandemic impact your family?” Based on participants’ responses, the interview was further explored with probing and interpretative questions like: “Could you elaborate on that?” Or “did you mean to say that...?”

After the interview, participants were provided information on contacting the researcher in case they wished to share additional details, amend their responses, or withdraw from the study. The interviewer also noted participants’ verbal, physical, and emotional reactions and any pauses or silences for use in the subsequent content analysis. Each interview was transcribed verbatim, and semantic units and initial codes were assigned. The initial codes were reviewed and refined through repeated analysis and then organized into categories and subcategories based on thematic similarities and differences.

The validity and rigor of the research data were ensured through the four criteria of reliability in qualitative research: Credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability, as outlined by Graneheim and Lundman [32]. Several strategies were employed to enhance the credibility of the research. The researcher maintained continuous engagement with the data to foster immersion and established ongoing communication with participants to review and clarify points raised in their quotes. Additionally, maximum diversity in the selected samples was ensured in terms of age, gender, educational level and job position. Supervisors and advisors facilitated data reviews during weekly and monthly meetings.

The dependability and trustworthiness of the data were ensured through external and continuous monitoring of the research stages and data collection by supervisors and advisors, who provided corrective feedback throughout the research process, particularly during data collection. To establish confirmability, which relates to the integrity of the data and the absence of bias, the researcher made a conscious effort to avoid imposing personal assumptions during data collection and analysis. Additionally, select interviews, codes, and categories developed by the research team and two qualitative research experts were reviewed to verify coding accuracy. For transferability, the researcher focused on several factors: Acknowledging the social and cultural backgrounds of the participants, defining clear criteria for participant selection (including conditions for entering or exiting the study), and employing specific methods for data collection and analysis. Concrete examples of participant quotes were also included to enhance the transferability of the findings to similar groups and contexts.

Results

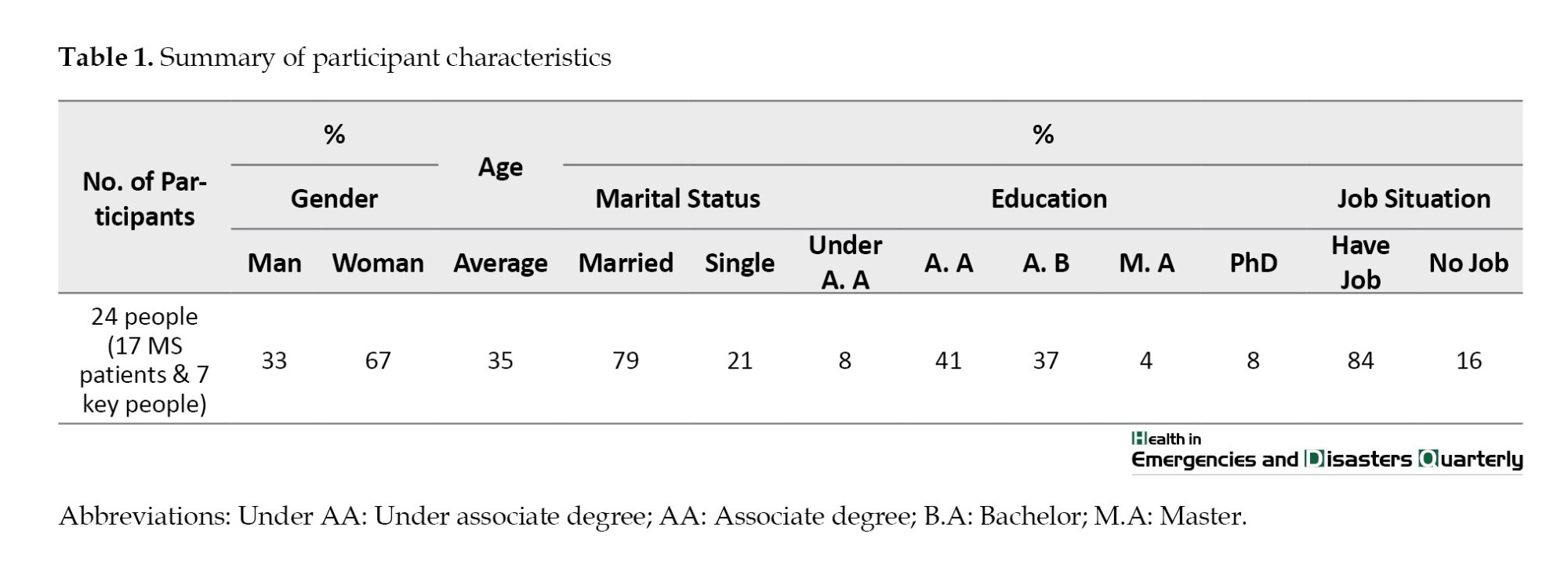

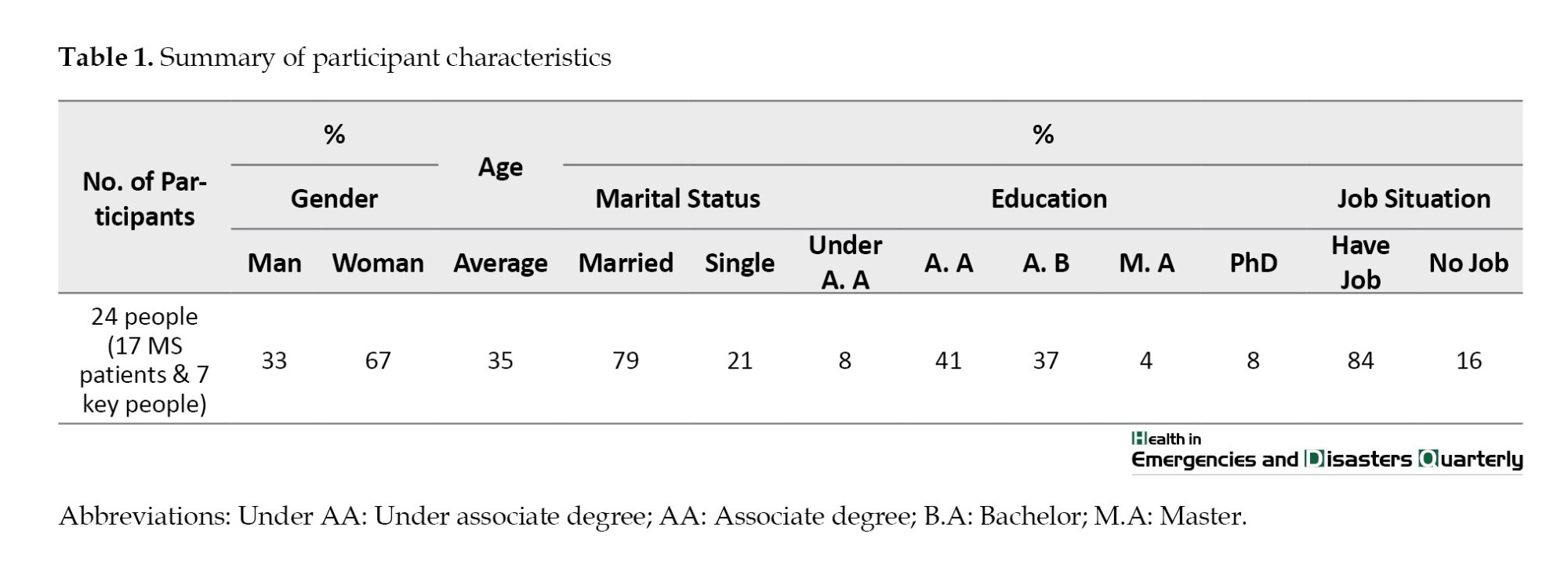

This research explored the personal, family and social experiences of patients with MS during the COVID-19 pandemic from the winter of 2022 to the summer of 2022 in Ardabil City, Iran. The demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

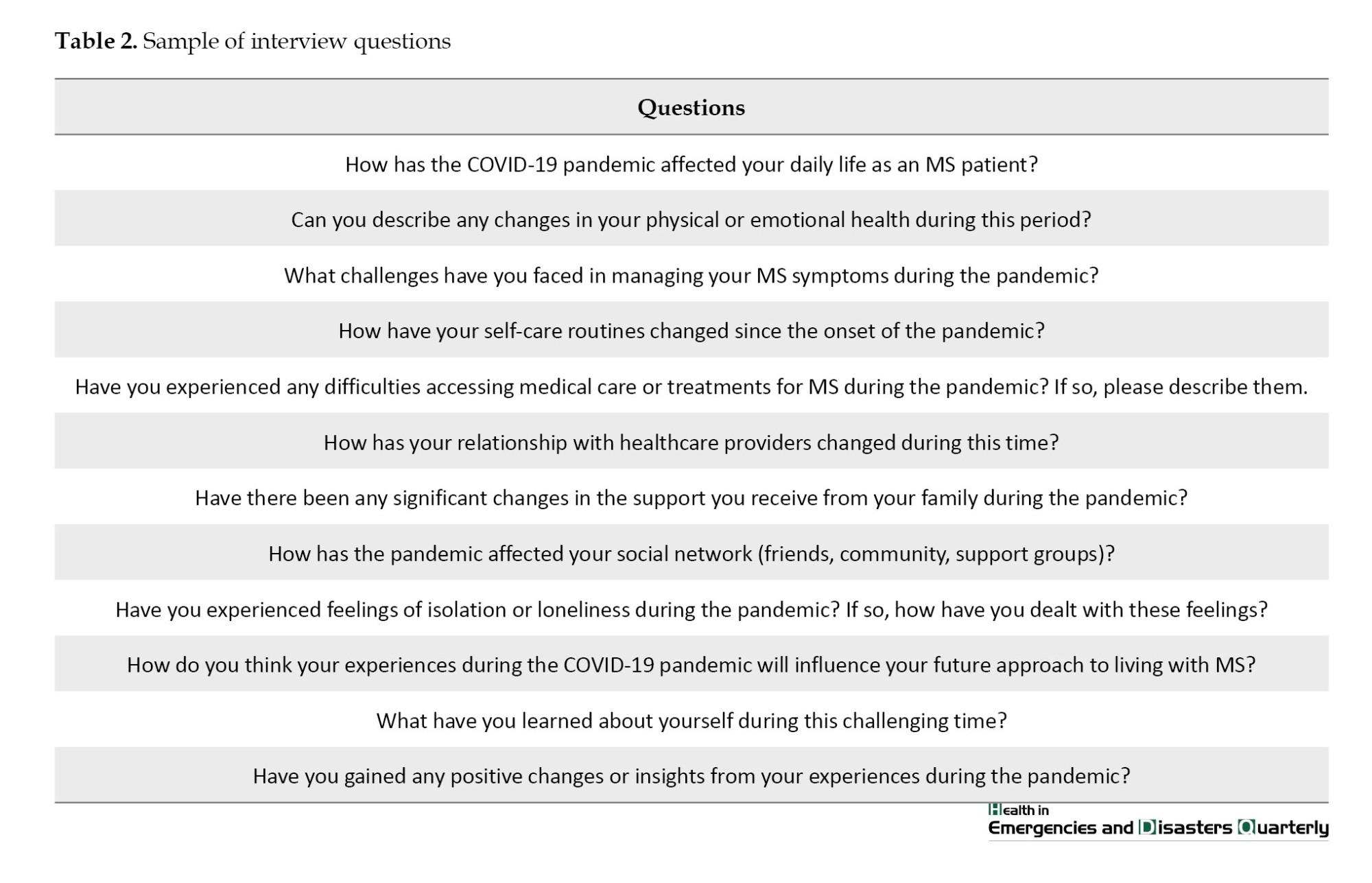

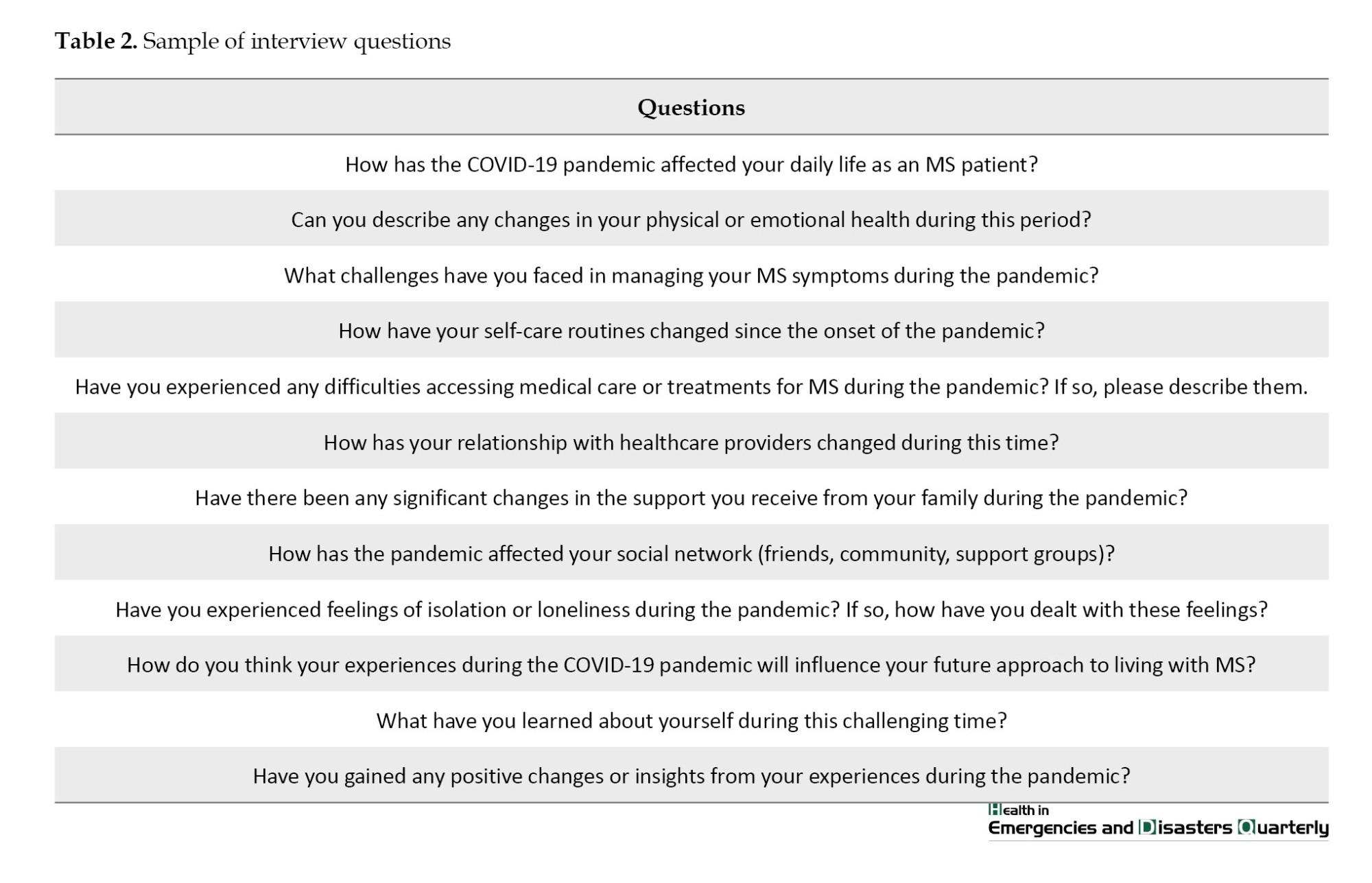

A sample of interview questions is mentioned in Table 2.

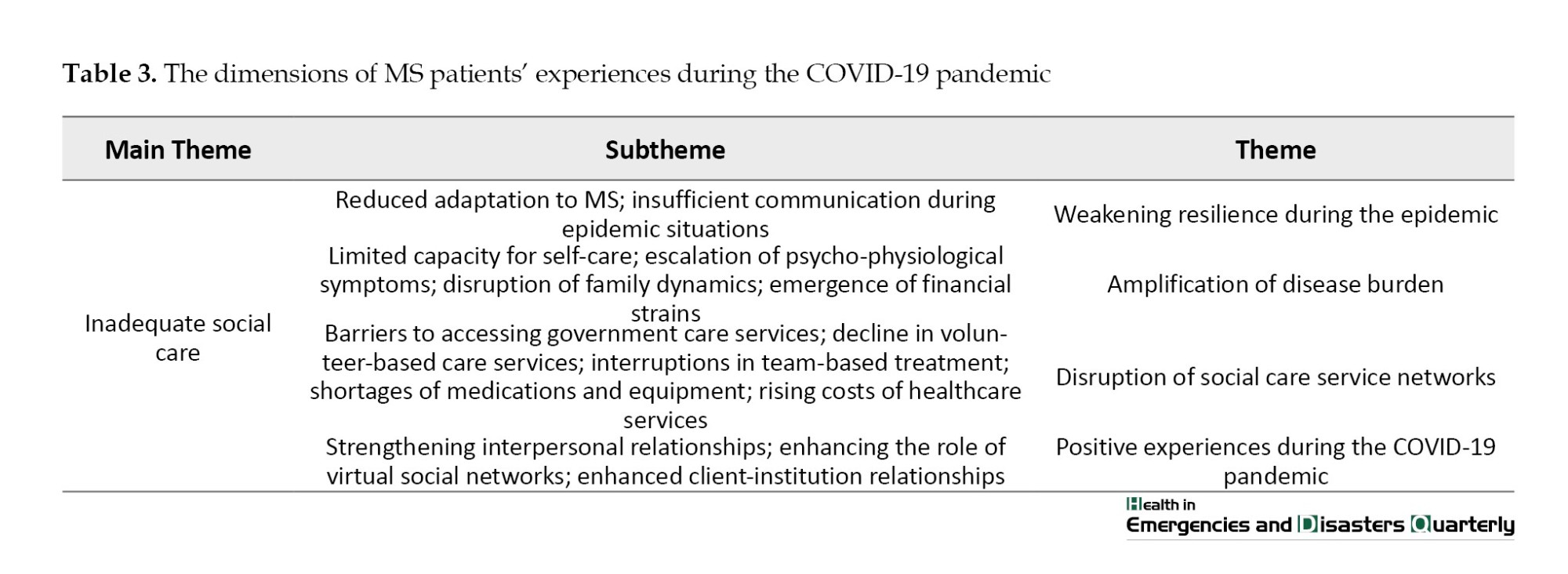

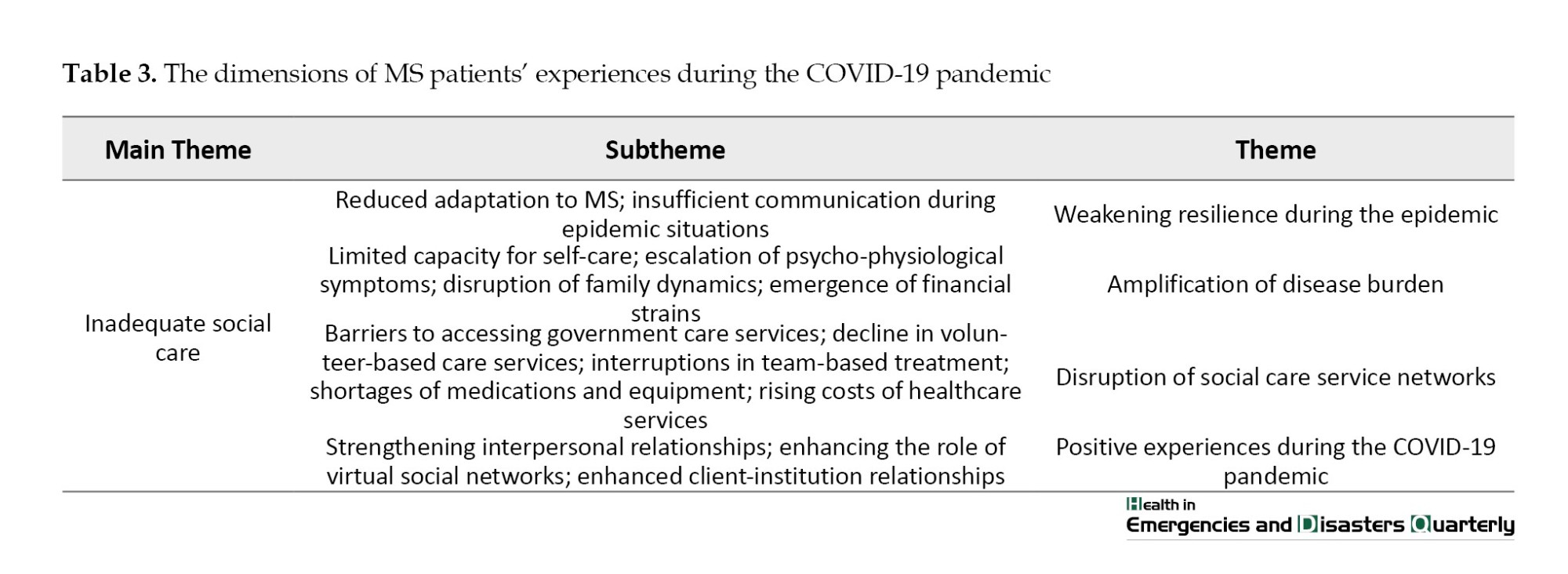

The final results of the data analysis are presented in detail in Table 3, comprising 835 semantic units, 14 subthemes and 4 overarching themes.

Theme 1: Weakening resilience during the epidemic

This theme indicates that the lack of acceptance of MS and insufficient information regarding the disease and its care during critical conditions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have undermined patients’ resilience and reduced their ability to adapt to the pandemic’s challenges effectively.

Reduced adaptation to MS

This subtheme reflects the experiences reported by most participants, indicating that before the COVID-19 pandemic, societal awareness of MS was low. Consequently, MS patients were often perceived as disabled individuals who imposed a burden on their families and society. This negative self-image has diminished both the acceptance of the disease by patients and their families, while the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this sense of incompatibility:

“I gave them an example; I said that now I am like a broken-down car on the side of the highway” (Participant [P]1).

Insufficient communication during epidemic situations

In this subtheme, participants expressed concerns regarding the general public’s lack of awareness and misinformation about MS, often stemming from portrayals in films and television series. Additionally, many participants highlighted the insufficient information available to MS patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the exaggerated portrayal of the risks associated with COVID-19 for individuals with MS. They also noted the absence of appropriate guidance on managing MS during the pandemic in the mass media. One participant articulated this sentiment:

“On the radio and television, they discussed the coronavirus epidemic as if getting infected meant certain death. If you survived, you would surely be incapacitated! The news made it seem as though a virus had been released that would turn us into zombies! I really felt that way. The radio and television did not give us proper information” (P7).

Theme 2: Amplification of disease burden

This theme reflects the participants’ experiences regarding the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on exacerbating the burden of MS. The limitations on self-care, intensified psychological and physiological complications, disruptions in family interactions and the emergence of livelihood challenges have all contributed to an increased burden of the disease. Consequently, many participants reported spending the majority of their days experiencing fatigue and disability.

Limited capacity for self-care

This subtheme addresses the impact of the critical conditions surrounding the coronavirus on the routine and standard care of MS patients. As one participant noted:

“Due to the stress and fear associated with the coronavirus, I did not adhere to my routine MS treatments. For example, I refrained from taking corticosteroids because they made me feel weak. As a taxi driver, I could not afford to be physically weak while behind the wheel” (P1).

Escalation of psycho-physiological symptoms

This subtheme, which included the most primary codes, highlighted the wide range of anxiety, mood disorders, stress and psychosomatic issues experienced by MS patients during the coronavirus pandemic. These issues encompassed isolation, depression, fatigue, aggression, circadian rhythm disturbances, and relapses of MS exacerbated by the mental pressure stemming from the pandemic. One participant described experiences:

“In June 2019, my MS relapsed again due to factors such as the stress of potentially not finding the medication, the lack of available treatments, and the unavailability of a specialist doctor with whom I felt comfortable. Additionally, the delay in administering my medication and problems related to renewing my insurance contributed to my distress” (P7).

Disruption of family dynamics

This subtheme explores the family experiences of MS patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the participants, they faced disruptions in their marital and emotional relationships, as well as in the interactions between parents and children and among siblings during the pandemic. One participant noted:

“Our marital relationship was weak before, and it became even weaker when the epidemic started. He keeps telling me that I don’t have enough energy for a marital relationship” (P10).

Another participant expressed

“It was very difficult for me because of my son. I am very sensitive about his studies, and I even took it hard and imposed strict expectations” (P2).

Emergence of financial strains

This subtheme reflects the experiences of MS patients and their families regarding livelihood and economic challenges during the pandemic. Participants reported issues such as reduced working hours and family income, workplace closures, lack of direct financial support from the government, insufficient funds to purchase medication and nutritious food, children dropping out of school due to economic hardship and an inability to maintain routine medical care. One participant shared:

“It’s not the old days anymore; I’m very careful with my expenses. During the pandemic, we reduced our spending on food, clothing and entertainment, prioritizing our medication and treatment during this time” (P8).

Theme 3: Disruption of social care service networks

This theme was derived from the analysis of five subthemes: Impairment of team-based treatment, limited access to government care services, reduction of voluntary network care services, increased healthcare costs and shortages of medications and medical equipment.

Barriers to accessing government care services

In this subtheme, participants discussed their lack of access to, or the difficulties in accessing, government health and medical services during the pandemic:

“The government hospital was extremely dirty and overcrowded. There were no suitable rooms or beds for patients. It felt as crowded as a women’s restroom and did not provide a sense of comfort or privacy. The arrangement of the beds was also poor, offering no mental peace at all” (P6).

“If we had an MS patient who contracted the coronavirus, we were not notified. They would only call if there were a chance to inform us; otherwise, we would remain uninformed” (P24).

Decline in volunteer-based care services

This subtheme reflects the experiences of participants, both as individuals living with MS and as providers of specialized services to MS patients, regarding the lack of progress or stagnation of non-governmental and voluntary medical and care services during the pandemic:

“During the pandemic, there was so much fear that non-governmental organizations with limited financial resources were practically reluctant to take action or raise awareness” (P20).

Interruptions in team-based treatment

In this subtheme, participants shared their experiences regarding the lack of collaborative care networks, which include doctors, psychiatrists and counselors:

“During the pandemic, when everyone was anxious, it would have been beneficial to form a team and utilize available resources to alleviate anxiety” (P18).

“I can say from a clinical and medical perspective that all necessary actions were taken in terms of diagnosis and medication prescription. However, I have no information about collaborative care, such as rehabilitation services, social work, and counseling” (P21).

Shortage of medication and equipment

This subtheme reflects the participants’ experiences regarding the scarcity of essential and supplementary MS medications. It highlights the unavailability of specific care devices, such as rehabilitation equipment, during the coronavirus pandemic:

“Every time I went to the Red Crescent, I witnessed one or two people arguing over the unavailability of a specific medication” (P4).

“During the pandemic, I was overwhelmed by the fear that actovex would not be available due to the new wave of rising prices and economic inflation and that I would have to resort to using cinnovex” (P7).

Rising costs of healthcare services

This subtheme addresses the changes in medication prices and costs associated with inpatient and outpatient services in public hospitals, which emerged due to increased economic instability (exacerbated by international economic sanctions against Iran) during the coronavirus pandemic. This situation led to significant challenges for MS patients in obtaining their medications and routine care:

“Before the pandemic, hospital services were free, but now, during the pandemic, we have to pay for treatments, including serums and injections; only the emergency corticosteroids are provided at no cost” (P13).

“Previously, there was a 50% subsidy for foreign medications, but during the pandemic, this subsidy decreased to 10%” (P22).

Theme 4: Positive experiences during the covid-19 pandemic

This theme highlights the positive experiences of participants during the coronavirus pandemic. It consists of four subthemes: Strengthening interpersonal relationships, enhancing the role of virtual social networks, and improving the relationship between clients and institutions.

Strengthening interpersonal relationships

This subcategory indicates that the relationships among friends and relatives of MS patients were strengthened due to pandemic-related restrictions, such as home quarantines, which led to a greater appreciation for one another.

“Coronavirus gave people motivation! For example, people appreciated each other more; gatherings indeed decreased, but individuals recognized each other’s value more” (P12).

Enhancing the role of virtual social networks

This subtheme pertains to the role of virtual social networks in facilitating leisure activities, obtaining information, providing entertainment, and fostering social interactions during the pandemic, particularly during home quarantine.

“I had a page on Instagram that was a fan page for one of the singers, and it had many members. During this time, I tried to manage the page. I also studied and watched movies, which helped me feel better” (P4).

Enhanced client-institution relationships

The final subtheme pertains to enhancing the relationship between clients (MS patients) and the institution (the MS Association). Participants discussed various aspects of this relationship, including communication between MS patients and the Association, interactions among patients facilitated by the association, the Association’s efforts to provide rare medications and health supplies, and outreach to patients during the pandemic.

“Sometimes, when the MS Association calls to inquire about our medications, it has a very positive effect on us. It is reassuring to know that someone is thinking of me” (P8).

Discussion

This research aimed to explore the personal, family, and social experiences of patients with MS during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ardabil. The findings reveal that poor acceptance or low adaptation to MS, coupled with insufficient health information, reduced patients’ resilience during the pandemic. The inability to adapt effectively made many patients struggle with planning their personal, family and social lives. In some cases, much of their energy was spent proving they were no different from healthy individuals. As a result, many doctors’ recommendations and health protocols were disregarded. These findings are consistent with studies indicating that challenges in managing energy and fatigue among MS patients can trigger relapses and disrupt care follow-ups [33-35]. Furthermore, a lack of acceptance of the disease by patients or their families can reduce resilience [36], highlighting the need for educational and therapeutic interventions to address this issue for both patients and their families [37-39].

Concerning the lack of accurate information during the crisis, this research revealed that specific mass media programs have contributed to the creation of harmful stereotypes about MS patients and their capabilities, which has led to difficulties in gaining acceptance from both family and society. The combination of society’s flawed perceptions of MS with exaggerated media coverage about their heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 has intensified anxiety and fear among MS patients. Although research indicates that many people prefer receiving COVID-19-related news through mass media rather than from friends or social networks [40], participants in this study expressed a preference for obtaining pandemic updates through friends or virtual networks due to a lack of trust in mass media, concerns about exaggerated reports, and insufficient information tailored to the lifestyles of MS patients during the pandemic. These findings, which highlight the need for accurate information for MS patients and the role of mass media in promoting preventive and care behaviors, align with existing studies [35, 40-43].

The increased psychological, social, and economic burden on MS patients during the COVID-19 pandemic is another key finding of this research. The crisis caused these patients to experience heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and mood disorders, which disrupted their daily lives and strained family interactions. This condition, in turn, led to MS relapses as patients delayed necessary care, resulting in significant direct and indirect costs for the patients, their families, and society. These findings align with previous research that highlights the growing burden of MS [44, 45], the impact of the pandemic on delayed self-care [22], the prevalence of debilitating mental health symptoms [6, 20, 21, 26, 41] and the role of psychological distress in reducing treatment adherence and triggering relapses [46, 47].

Another key finding of this research is the limited access to governmental, non-governmental, and voluntary care services for MS patients during the pandemic. Additionally, the lack of communication with patients regarding available care services contributed to their inability to access regular and team-based care, such as medical consultations, physical therapy and mental health support. These results align with studies emphasizing the importance of integrated care services for patients [24, 34], the disruption of healthcare services during crises [48], the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare systems [22] and the role of social support networks in aiding vulnerable populations [49]. In addition to the challenges previously mentioned, the overlap of the coronavirus crisis with severe economic instability—triggered by a new wave of international sanctions on Iran—exacerbated the shortage of medicines and medical equipment. This condition caused a significant increase in healthcare costs, particularly for MS patients. As a result, many patients could not access routine care, medications, and necessary equipment [30, 50], thus violating their right to health, a fundamental human right according to the United Nations charter.

Despite these difficulties, the pandemic also brought positive experiences for patients, such as strengthening interpersonal relationships, enhancing the role of virtual social networks, and improving the connection between patients and institutions like the MS Association. Related research findings also reflect these positive outcomes [49, 51]. To ensure effective support for MS patients during crises, healthcare professionals must prioritize the establishment of integrated care teams that provide regular medical care, psychological support, and rehabilitation services. Policymakers should focus on improving the accessibility and affordability of essential medications and healthcare services by enhancing insurance coverage and addressing supply chain disruptions. Furthermore, public health campaigns should be tailored to disseminate accurate and accessible information on managing chronic conditions like MS during critical periods. Support organizations also play a crucial role and should expand their outreach by leveraging virtual platforms to provide psychological counseling and peer support, reducing isolation and fostering resilience among MS patients. Implementing these targeted measures will help mitigate the unique challenges faced by this vulnerable population and ensure that their care and support needs are met in future crises.

Conclusion

Based on the research findings, MS patients’ preparedness and response to crises like the COVID-19 pandemic are influenced by their ability to adapt to their condition and their knowledge of both MS and the pandemic. Their capacity to apply this knowledge effectively is crucial for managing their chronic illness in critical situations. Public health experts should consider these findings in psychological and social interventions. The pandemic disrupted MS patients’ living conditions, family dynamics, and well-being, leading to delays in care and symptom management, which increased their burden of disease. Additionally, inadequate coordination between care systems and the lack of support from formal and informal networks exacerbated the neglect of MS patients during the pandemic. Furthermore, MS patients faced three simultaneous crises: The disease itself, the economic challenges worsened by international sanctions, and the pandemic. These compounded difficulties in accessing medications, medical equipment and health insurance infringe on their rights to health and dignity and reduce their motivation for self-care, ultimately diminish their quality of life. The insights from this study can inform the development of targeted policies and interventions for MS patients during the pandemic, helping them manage their challenges. This research advances knowledge in the field and offers practical guidance for addressing the unique needs of this population.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR. REC.1400. 256).

Funding

This article is extracted from the master’s thesis of Soraya Hamidi Razey, approved by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Soraya Hamidi Razey, and Fardin Alipour; Supervision: Fardin Alipour, Leila Ostad Hashemi, and Mohammad Sabzi Khoshnami; Data analysis: Soraya Hamidi Razey, and Leila Ostad Hashemi; Data interpretation: Soraya Hamidi Razey, and Mohammad Sabzi Khoshnami; Data collection and writing the original draft: Soraya Hamidi Razey; Review and editing: Soraya Hamidi Razey, Fardin Alipour, Foroogh Elyasi and Mostafa Mardani; Critical revision: Foroogh Elyasi, and Mostafa Mardani; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the Ardabil MS Society and the participants who helped us during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system that disrupts the myelin sheath, resulting in physical impairments and associated mental health challenges [1]. Typically manifesting between the ages of 20 and 40, MS affects women at twice the rate of men. Key symptoms include weakness, fatigue, sensory-motor nerve dysfunction, and cognitive or mood disturbances [2]. With a relatively higher prevalence among chronic neurological conditions, MS requires management focused on maintenance and patient care due to its progressive and incurable nature [3]. Globally, the prevalence of MS was estimated at 35.9 per 100000 in 2020, marking a significant increase since 2013 [4]. In Iran, the prevalence is notably higher, at approximately 100 per 100000, designating it as a high-prevalence region [5-9]. Rates vary significantly by area in Iran, with Tehran Province reporting the highest prevalence and provinces like Khuzestan and Sistan-Baluchestan the lowest [10]. Notably, the prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran continue to rise [10], surpassing those in some neighboring Middle Eastern countries [9].

Emerged in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, the COVID-19 pandemic rapidly became a global health crisis, impacting personal, familial and psychological well-being through social distancing and travel restrictions [11]. Among vulnerable populations, MS patients faced unique challenges related to lifestyle, health and treatment despite MS itself not increasing COVID-19 mortality risk [12, 13]. Patients undergoing disease-modifying therapies were particularly vulnerable to infections and heightened emotional disorders, including anxiety, stress, anger, and stigma, exacerbated by quarantine and uncertainty [14, 15]. Depression and anxiety, common among MS patients, further diminished their quality of life and treatment adherence [16]. While MS patients’ infection and mortality rates from COVID-19 were similar to the general population (3-6%), their hospitalization rates were significantly higher [17-19]. Fatigue, a prevalent and debilitating symptom in approximately 80% of MS patients [3] and heightened sensitivity to stressors, which may trigger relapses [16], added to their burden [20]. Addressing the pandemic’s less visible psychological and stress-related impacts could mitigate disease severity and recurrence [20].

Most international researchers have descriptively examined the personal and psychological effects of the coronavirus pandemic on MS patients [21-23]. In some cases, they have also addressed its social and occupational consequences [24, 25]. Domestic studies, on the other hand, have primarily focused on the psychological effects of the pandemic on MS patients [6, 20] or have investigated the psychological impact of MS in non-crisis periods before the COVID-19 pandemic [26, 27]. It is also important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with a new wave of international economic sanctions against Iran, creating unique challenges for chronic patients, including those with MS, which appear to have affected their care and health [28-30].

Existing studies emphasize the need further to explore MS patients’ experiences during epidemics like COVID-19 to inform therapeutic approaches and theoretical models. Comprehensive research can deepen understanding of these patients’ unique needs, fostering advancements in the field. This study aims to holistically examine shared human experiences by synthesizing qualitative findings, offering insights to shape services and interventions for rehabilitating MS patients during epidemics. By reviewing past experiences, the research seeks to identify gaps, analyze key issues, and determine necessary services and measures to address the multifaceted impacts of epidemics on MS patients.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative research employs a methodology grounded in the philosophy of naturalism, focusing on studying a natural phenomenon—the COVID-19 pandemic—through a holistic perspective. The patients’ experiences were examined holistically, considering their environment, context, values, daily perceptions, personal biographies, and factors related to these patients. Given the lack of sufficient theoretical resources, the analysis was conducted using a contract content analysis model based on Lundman and Granheim’s approach [31], which enabled a deep and systematic identification of the individual, familial, and social experiences of people with MS during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research was conducted in Ardabil and the participants included 24 individuals: 17 MS patients aged at least 18 years and 7 experts with significant experience working with MS patients. Participants were selected through purposive sampling, guided by specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, and employing a maximum diversity approach. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: Participants must be over 18 years old, have a minimum disease duration of one year, and provide written informed consent to participate. The exclusion criteria included the presence of cognitive disorders, mental health issues requiring treatment for three months or less and unwillingness to participate in the study. Additionally, specialists in the study must have at least three years of experience working with MS patients. The selection of participants continued until data saturation was reached. Research data were collected through semi-structured interviews between the winter of 2022 and the summer of 2022, following the necessary permissions and adherence to general ethical guidelines and specific ethical codes pertaining to vulnerable groups in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Some of these general ethical guidelines included providing special protection for participating patients, informing participants about the purpose of the research, obtaining informed consent, and ensuring professional confidentiality.

Given the special circumstances surrounding the coronavirus in the country and in accordance with the regulations set by the Corona Management Headquarters, most interviews were conducted when there were no commuting restrictions in the city. During the peak of the pandemic restrictions, some interviews were held online through social networks. The timing and location of the interviews were arranged to accommodate the participants’ convenience while adhering to health protocols specified by the Corona Management Headquarters, such as using air conditioning, wearing masks, and maintaining a safe distance. The interviews ranged from 30 to 80 minutes, depending on the patient’s condition, willingness to engage in conversation, and the nature and extent of their experiences.

Moreover, with a commitment to safeguarding confidentiality in handling information and interviews, all participants were assured that only the researcher would have access to these materials. In addition, confidentiality principles were followed, and participants were assured of privacy. Detailed explanations of the study’s protocols were provided to them, accompanied by written informed consent for their review and signature. Informed consent was obtained from all participants to record the interviews. To build rapport and ease participants into the process, the initial questions were open-ended and interpretative, such as: “How many years have you been living with MS?” and “Could you describe the first few days after your diagnosis?” As trust was established and participants became more comfortable, more specific questions followed, such as: “How did the coronavirus pandemic begin for you?” Or “how did the pandemic impact your family?” Based on participants’ responses, the interview was further explored with probing and interpretative questions like: “Could you elaborate on that?” Or “did you mean to say that...?”

After the interview, participants were provided information on contacting the researcher in case they wished to share additional details, amend their responses, or withdraw from the study. The interviewer also noted participants’ verbal, physical, and emotional reactions and any pauses or silences for use in the subsequent content analysis. Each interview was transcribed verbatim, and semantic units and initial codes were assigned. The initial codes were reviewed and refined through repeated analysis and then organized into categories and subcategories based on thematic similarities and differences.

The validity and rigor of the research data were ensured through the four criteria of reliability in qualitative research: Credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability, as outlined by Graneheim and Lundman [32]. Several strategies were employed to enhance the credibility of the research. The researcher maintained continuous engagement with the data to foster immersion and established ongoing communication with participants to review and clarify points raised in their quotes. Additionally, maximum diversity in the selected samples was ensured in terms of age, gender, educational level and job position. Supervisors and advisors facilitated data reviews during weekly and monthly meetings.

The dependability and trustworthiness of the data were ensured through external and continuous monitoring of the research stages and data collection by supervisors and advisors, who provided corrective feedback throughout the research process, particularly during data collection. To establish confirmability, which relates to the integrity of the data and the absence of bias, the researcher made a conscious effort to avoid imposing personal assumptions during data collection and analysis. Additionally, select interviews, codes, and categories developed by the research team and two qualitative research experts were reviewed to verify coding accuracy. For transferability, the researcher focused on several factors: Acknowledging the social and cultural backgrounds of the participants, defining clear criteria for participant selection (including conditions for entering or exiting the study), and employing specific methods for data collection and analysis. Concrete examples of participant quotes were also included to enhance the transferability of the findings to similar groups and contexts.

Results

This research explored the personal, family and social experiences of patients with MS during the COVID-19 pandemic from the winter of 2022 to the summer of 2022 in Ardabil City, Iran. The demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

A sample of interview questions is mentioned in Table 2.

The final results of the data analysis are presented in detail in Table 3, comprising 835 semantic units, 14 subthemes and 4 overarching themes.

Theme 1: Weakening resilience during the epidemic

This theme indicates that the lack of acceptance of MS and insufficient information regarding the disease and its care during critical conditions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have undermined patients’ resilience and reduced their ability to adapt to the pandemic’s challenges effectively.

Reduced adaptation to MS

This subtheme reflects the experiences reported by most participants, indicating that before the COVID-19 pandemic, societal awareness of MS was low. Consequently, MS patients were often perceived as disabled individuals who imposed a burden on their families and society. This negative self-image has diminished both the acceptance of the disease by patients and their families, while the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this sense of incompatibility:

“I gave them an example; I said that now I am like a broken-down car on the side of the highway” (Participant [P]1).

Insufficient communication during epidemic situations

In this subtheme, participants expressed concerns regarding the general public’s lack of awareness and misinformation about MS, often stemming from portrayals in films and television series. Additionally, many participants highlighted the insufficient information available to MS patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the exaggerated portrayal of the risks associated with COVID-19 for individuals with MS. They also noted the absence of appropriate guidance on managing MS during the pandemic in the mass media. One participant articulated this sentiment:

“On the radio and television, they discussed the coronavirus epidemic as if getting infected meant certain death. If you survived, you would surely be incapacitated! The news made it seem as though a virus had been released that would turn us into zombies! I really felt that way. The radio and television did not give us proper information” (P7).

Theme 2: Amplification of disease burden

This theme reflects the participants’ experiences regarding the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on exacerbating the burden of MS. The limitations on self-care, intensified psychological and physiological complications, disruptions in family interactions and the emergence of livelihood challenges have all contributed to an increased burden of the disease. Consequently, many participants reported spending the majority of their days experiencing fatigue and disability.

Limited capacity for self-care

This subtheme addresses the impact of the critical conditions surrounding the coronavirus on the routine and standard care of MS patients. As one participant noted:

“Due to the stress and fear associated with the coronavirus, I did not adhere to my routine MS treatments. For example, I refrained from taking corticosteroids because they made me feel weak. As a taxi driver, I could not afford to be physically weak while behind the wheel” (P1).

Escalation of psycho-physiological symptoms

This subtheme, which included the most primary codes, highlighted the wide range of anxiety, mood disorders, stress and psychosomatic issues experienced by MS patients during the coronavirus pandemic. These issues encompassed isolation, depression, fatigue, aggression, circadian rhythm disturbances, and relapses of MS exacerbated by the mental pressure stemming from the pandemic. One participant described experiences:

“In June 2019, my MS relapsed again due to factors such as the stress of potentially not finding the medication, the lack of available treatments, and the unavailability of a specialist doctor with whom I felt comfortable. Additionally, the delay in administering my medication and problems related to renewing my insurance contributed to my distress” (P7).

Disruption of family dynamics

This subtheme explores the family experiences of MS patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the participants, they faced disruptions in their marital and emotional relationships, as well as in the interactions between parents and children and among siblings during the pandemic. One participant noted:

“Our marital relationship was weak before, and it became even weaker when the epidemic started. He keeps telling me that I don’t have enough energy for a marital relationship” (P10).

Another participant expressed

“It was very difficult for me because of my son. I am very sensitive about his studies, and I even took it hard and imposed strict expectations” (P2).

Emergence of financial strains

This subtheme reflects the experiences of MS patients and their families regarding livelihood and economic challenges during the pandemic. Participants reported issues such as reduced working hours and family income, workplace closures, lack of direct financial support from the government, insufficient funds to purchase medication and nutritious food, children dropping out of school due to economic hardship and an inability to maintain routine medical care. One participant shared:

“It’s not the old days anymore; I’m very careful with my expenses. During the pandemic, we reduced our spending on food, clothing and entertainment, prioritizing our medication and treatment during this time” (P8).

Theme 3: Disruption of social care service networks

This theme was derived from the analysis of five subthemes: Impairment of team-based treatment, limited access to government care services, reduction of voluntary network care services, increased healthcare costs and shortages of medications and medical equipment.

Barriers to accessing government care services

In this subtheme, participants discussed their lack of access to, or the difficulties in accessing, government health and medical services during the pandemic:

“The government hospital was extremely dirty and overcrowded. There were no suitable rooms or beds for patients. It felt as crowded as a women’s restroom and did not provide a sense of comfort or privacy. The arrangement of the beds was also poor, offering no mental peace at all” (P6).

“If we had an MS patient who contracted the coronavirus, we were not notified. They would only call if there were a chance to inform us; otherwise, we would remain uninformed” (P24).

Decline in volunteer-based care services

This subtheme reflects the experiences of participants, both as individuals living with MS and as providers of specialized services to MS patients, regarding the lack of progress or stagnation of non-governmental and voluntary medical and care services during the pandemic:

“During the pandemic, there was so much fear that non-governmental organizations with limited financial resources were practically reluctant to take action or raise awareness” (P20).

Interruptions in team-based treatment

In this subtheme, participants shared their experiences regarding the lack of collaborative care networks, which include doctors, psychiatrists and counselors:

“During the pandemic, when everyone was anxious, it would have been beneficial to form a team and utilize available resources to alleviate anxiety” (P18).

“I can say from a clinical and medical perspective that all necessary actions were taken in terms of diagnosis and medication prescription. However, I have no information about collaborative care, such as rehabilitation services, social work, and counseling” (P21).

Shortage of medication and equipment

This subtheme reflects the participants’ experiences regarding the scarcity of essential and supplementary MS medications. It highlights the unavailability of specific care devices, such as rehabilitation equipment, during the coronavirus pandemic:

“Every time I went to the Red Crescent, I witnessed one or two people arguing over the unavailability of a specific medication” (P4).

“During the pandemic, I was overwhelmed by the fear that actovex would not be available due to the new wave of rising prices and economic inflation and that I would have to resort to using cinnovex” (P7).

Rising costs of healthcare services

This subtheme addresses the changes in medication prices and costs associated with inpatient and outpatient services in public hospitals, which emerged due to increased economic instability (exacerbated by international economic sanctions against Iran) during the coronavirus pandemic. This situation led to significant challenges for MS patients in obtaining their medications and routine care:

“Before the pandemic, hospital services were free, but now, during the pandemic, we have to pay for treatments, including serums and injections; only the emergency corticosteroids are provided at no cost” (P13).

“Previously, there was a 50% subsidy for foreign medications, but during the pandemic, this subsidy decreased to 10%” (P22).

Theme 4: Positive experiences during the covid-19 pandemic

This theme highlights the positive experiences of participants during the coronavirus pandemic. It consists of four subthemes: Strengthening interpersonal relationships, enhancing the role of virtual social networks, and improving the relationship between clients and institutions.

Strengthening interpersonal relationships

This subcategory indicates that the relationships among friends and relatives of MS patients were strengthened due to pandemic-related restrictions, such as home quarantines, which led to a greater appreciation for one another.

“Coronavirus gave people motivation! For example, people appreciated each other more; gatherings indeed decreased, but individuals recognized each other’s value more” (P12).

Enhancing the role of virtual social networks

This subtheme pertains to the role of virtual social networks in facilitating leisure activities, obtaining information, providing entertainment, and fostering social interactions during the pandemic, particularly during home quarantine.

“I had a page on Instagram that was a fan page for one of the singers, and it had many members. During this time, I tried to manage the page. I also studied and watched movies, which helped me feel better” (P4).

Enhanced client-institution relationships

The final subtheme pertains to enhancing the relationship between clients (MS patients) and the institution (the MS Association). Participants discussed various aspects of this relationship, including communication between MS patients and the Association, interactions among patients facilitated by the association, the Association’s efforts to provide rare medications and health supplies, and outreach to patients during the pandemic.

“Sometimes, when the MS Association calls to inquire about our medications, it has a very positive effect on us. It is reassuring to know that someone is thinking of me” (P8).

Discussion

This research aimed to explore the personal, family, and social experiences of patients with MS during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ardabil. The findings reveal that poor acceptance or low adaptation to MS, coupled with insufficient health information, reduced patients’ resilience during the pandemic. The inability to adapt effectively made many patients struggle with planning their personal, family and social lives. In some cases, much of their energy was spent proving they were no different from healthy individuals. As a result, many doctors’ recommendations and health protocols were disregarded. These findings are consistent with studies indicating that challenges in managing energy and fatigue among MS patients can trigger relapses and disrupt care follow-ups [33-35]. Furthermore, a lack of acceptance of the disease by patients or their families can reduce resilience [36], highlighting the need for educational and therapeutic interventions to address this issue for both patients and their families [37-39].

Concerning the lack of accurate information during the crisis, this research revealed that specific mass media programs have contributed to the creation of harmful stereotypes about MS patients and their capabilities, which has led to difficulties in gaining acceptance from both family and society. The combination of society’s flawed perceptions of MS with exaggerated media coverage about their heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 has intensified anxiety and fear among MS patients. Although research indicates that many people prefer receiving COVID-19-related news through mass media rather than from friends or social networks [40], participants in this study expressed a preference for obtaining pandemic updates through friends or virtual networks due to a lack of trust in mass media, concerns about exaggerated reports, and insufficient information tailored to the lifestyles of MS patients during the pandemic. These findings, which highlight the need for accurate information for MS patients and the role of mass media in promoting preventive and care behaviors, align with existing studies [35, 40-43].

The increased psychological, social, and economic burden on MS patients during the COVID-19 pandemic is another key finding of this research. The crisis caused these patients to experience heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and mood disorders, which disrupted their daily lives and strained family interactions. This condition, in turn, led to MS relapses as patients delayed necessary care, resulting in significant direct and indirect costs for the patients, their families, and society. These findings align with previous research that highlights the growing burden of MS [44, 45], the impact of the pandemic on delayed self-care [22], the prevalence of debilitating mental health symptoms [6, 20, 21, 26, 41] and the role of psychological distress in reducing treatment adherence and triggering relapses [46, 47].

Another key finding of this research is the limited access to governmental, non-governmental, and voluntary care services for MS patients during the pandemic. Additionally, the lack of communication with patients regarding available care services contributed to their inability to access regular and team-based care, such as medical consultations, physical therapy and mental health support. These results align with studies emphasizing the importance of integrated care services for patients [24, 34], the disruption of healthcare services during crises [48], the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare systems [22] and the role of social support networks in aiding vulnerable populations [49]. In addition to the challenges previously mentioned, the overlap of the coronavirus crisis with severe economic instability—triggered by a new wave of international sanctions on Iran—exacerbated the shortage of medicines and medical equipment. This condition caused a significant increase in healthcare costs, particularly for MS patients. As a result, many patients could not access routine care, medications, and necessary equipment [30, 50], thus violating their right to health, a fundamental human right according to the United Nations charter.

Despite these difficulties, the pandemic also brought positive experiences for patients, such as strengthening interpersonal relationships, enhancing the role of virtual social networks, and improving the connection between patients and institutions like the MS Association. Related research findings also reflect these positive outcomes [49, 51]. To ensure effective support for MS patients during crises, healthcare professionals must prioritize the establishment of integrated care teams that provide regular medical care, psychological support, and rehabilitation services. Policymakers should focus on improving the accessibility and affordability of essential medications and healthcare services by enhancing insurance coverage and addressing supply chain disruptions. Furthermore, public health campaigns should be tailored to disseminate accurate and accessible information on managing chronic conditions like MS during critical periods. Support organizations also play a crucial role and should expand their outreach by leveraging virtual platforms to provide psychological counseling and peer support, reducing isolation and fostering resilience among MS patients. Implementing these targeted measures will help mitigate the unique challenges faced by this vulnerable population and ensure that their care and support needs are met in future crises.

Conclusion

Based on the research findings, MS patients’ preparedness and response to crises like the COVID-19 pandemic are influenced by their ability to adapt to their condition and their knowledge of both MS and the pandemic. Their capacity to apply this knowledge effectively is crucial for managing their chronic illness in critical situations. Public health experts should consider these findings in psychological and social interventions. The pandemic disrupted MS patients’ living conditions, family dynamics, and well-being, leading to delays in care and symptom management, which increased their burden of disease. Additionally, inadequate coordination between care systems and the lack of support from formal and informal networks exacerbated the neglect of MS patients during the pandemic. Furthermore, MS patients faced three simultaneous crises: The disease itself, the economic challenges worsened by international sanctions, and the pandemic. These compounded difficulties in accessing medications, medical equipment and health insurance infringe on their rights to health and dignity and reduce their motivation for self-care, ultimately diminish their quality of life. The insights from this study can inform the development of targeted policies and interventions for MS patients during the pandemic, helping them manage their challenges. This research advances knowledge in the field and offers practical guidance for addressing the unique needs of this population.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR. REC.1400. 256).

Funding

This article is extracted from the master’s thesis of Soraya Hamidi Razey, approved by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Soraya Hamidi Razey, and Fardin Alipour; Supervision: Fardin Alipour, Leila Ostad Hashemi, and Mohammad Sabzi Khoshnami; Data analysis: Soraya Hamidi Razey, and Leila Ostad Hashemi; Data interpretation: Soraya Hamidi Razey, and Mohammad Sabzi Khoshnami; Data collection and writing the original draft: Soraya Hamidi Razey; Review and editing: Soraya Hamidi Razey, Fardin Alipour, Foroogh Elyasi and Mostafa Mardani; Critical revision: Foroogh Elyasi, and Mostafa Mardani; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the Ardabil MS Society and the participants who helped us during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- Russell N, Gallagher S, Msetfi RM, Hayes S, Motl RW, Coote S. Experiences of people with multiple sclerosis participating in a social cognitive behavior change physical activity intervention. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2023; 39(5):954-62. [DOI:10.1080/09593985.2022.2030828] [PMID]

- Learmonth YC, Motl RW. Physical activity and exercise training in multiple sclerosis: A review and content analysis of qualitative research identifying perceived determinants and consequences. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2016; 38(13):1227-42. [DOI:10.3109/09638288.2015.1077397] [PMID]

- Ovšonková A, Hlinková E, Miertová M, Žiaková K. Selected social aspects in the life of patients with multiple sclerosis. KONTAKT-Journal of Nursing & Social Sciences Related to Health & Illness. 2020; 22(2):104-10. [DOI:10.32725/kont.2020.012]

- Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, Kaye W, Leray E, Marrie RA, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2020; 26(14):1816-21. [DOI:10.1177/1352458520970841] [PMID]

- Cheong WL, Mohan D, Warren N, Reidpath DD. Multiple sclerosis in the asia pacific region: A systematic review of a neglected neurological disease. Frontiers in Neurology. 2018; 9:432. [DOI:10.3389/fneur.2018.00432] [PMID]

- Shaygannejad V, Mirmosayyeb O, Nehzat N, Ghajarzadeh M. Fear of relapse, social support, and psychological well-being (depression, anxiety, and stress level) of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) during the COVID-19 pandemic stage. Neurological Sciences. 2021; 42(7):2615-8. [DOI:10.1007/s10072-021-05253-8] [PMID]

- Yamout BI, Assaad W, Tamim H, Mrabet S, Goueider R. Epidemiology and phenotypes of multiple sclerosis in the Middle East North Africa (MENA) region. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2020; 6(1):2055217319841881. [DOI:10.1177/2055217319841881] [PMID]

- Hosseinzadeh A, Baneshi M, Sedighi B, Kermanchi J, Haghdoost A. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in Iran: A nationwide, population-based study. Public Health. 2019; 175:138-44. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2019.07.013] [PMID]

- Azami M, YektaKooshali MH, Shohani M, Khorshidi A, Mahmudi L. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One. 2019; 14(4):e0214738. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0214738] [PMID]

- Mirmosayyeb O, Shaygannejad V, Bagherieh S, Hosseinabadi AM, Ghajarzadeh M. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurological Sciences. 2022; 43(1):233-41. [DOI:10.1007/s10072-021-05750-w] [PMID]

- Asgari M, Choubdari A, Skandari H. Exploring the life experiences of people with Corona Virus disease in personal,family and social relationships and strategies to prevent and control the psychological effects. Counseling Culture and Psycotherapy. 2021; 12(45):33-52. [DOI:10.22054/qccpc.2020.53244.2453]

- Barzegar M, Mirmosayyeb O, Gajarzadeh M, Afshari-Safavi A, Nehzat N, Vaheb S, et al. COVID-19 among patients with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Neurology. 2021; 8(4):e1001. [DOI:10.1212/NXI.0000000000001001] [PMID]

- Bsteh G, Bitschnau C, Hegen H, Auer M, Di Pauli F, Rommer P, et al. Multiple sclerosis and COVID‐19: How many are at risk? European Journal of Neurology. 2021; 28(10):3369-74. [DOI:10.1111/ene.14555] [PMID]

- Flaherty GT, Hession P, Liew CH, Lim BCW, Leong TK, Lim V, et al. COVID-19 in adult patients with pre-existing chronic cardiac, respiratory and metabolic disease: A critical literature review with clinical recommendations. Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines. 2020; 6:16 [DOI:10.1186/s40794-020-00118-y] [PMID]

- Nesbitt C, Rath L, Yeh WZ, Zhong M, Wesselingh R, Monif M, et al. MSCOVID19: Using social media to achieve rapid dissemination of health information. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2020; 45:102338. [DOI:10.1016/j.msard.2020.102338] [PMID]

- Kang C, Yang S, Yuan J, Xu L, Zhao X, Yang J. Patients with chronic illness urgently need integrated physical and psychological care during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020; 51:102081. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102081] [PMID]

- Möhn N, Konen FF, Pul R, Kleinschnitz C, Prüss H, Witte T, et al. Experience in multiple sclerosis patients with COVID-19 and disease-modifying therapies: A review of 873 published cases. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(12):4067. [DOI:10.3390/jcm9124067] [PMID]

- Naser Moghadasi A. Evaluation of the level of anxiety among iranian multiple sclerosis fellowships during the outbreak of COVID-19. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2020; 23(4):283. [DOI:10.34172/aim.2020.13] [PMID]

- Loonstra FC, Hoitsma E, van Kempen ZL, Killestein J, Mostert JP. COVID-19 in multiple sclerosis: The Dutch experience. Multiple Sclerosis. 2020; 26(10):1256-60. [DOI:10.1177/1352458520942198] [PMID]

- Naser Moghadasi A. One aspect of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Iran: High anxiety among MS patients. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2020; 41:102138. [DOI:10.1016/j.msard.2020.102138] [PMID]

- Motolese F, Rossi M, Albergo G, Stelitano D, Villanova M, Di Lazzaro V, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with multiple sclerosis. Frontiers in Neurology. 2020; 11:580507. [DOI:10.3389/fneur.2020.580507] [PMID]

- Vogel AC, Schmidt H, Loud S, McBurney R, Mateen FJ. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health care of >1,000 People living with multiple sclerosis: A cross-sectional study. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2020; 46:102512. [DOI:10.1016/j.msard.2020.102512] [PMID]

- Morris-Bankole H, Ho AK. The COVID-19 pandemic experience in multiple sclerosis: The good, the bad and the neutral. Neurology and Therapy. 2021; 10(1):279-91. [DOI:10.1007/s40120-021-00241-8] [PMID]

- Sastre-Garriga J, Tintoré M, Montalban X. Keeping standards of multiple sclerosis care through the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2020; 26(10):1153-6. [DOI:10.1177/1352458520931785] [PMID]

- Zhang GX, Sanabria C, Martinez D, Zhang WT, Gao SS, Alemán A, et al. Social and professional consequences of COVID-19 lockdown in patients with multiple sclerosis from 2 very different populations. Neurología. 2021; 36(1):16-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.nrleng.2020.08.007]

- Zarei M, Hasanzade MA, Sheykh S. [Assessment of the prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression in multiple sclerosis patients conducted in Zahedan (Persian)]. Beyhagh. 2015; 19(3):13-21. [Link]

- Shabany M, Ayoubi S, Naser Moghadasi A, Najafi M, Eskandarieh S. Explaining the individual challenges of women affected by neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis: A comparative content analysis Study. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2021; 207:106789. [DOI:10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106789] [PMID]

- Cheraghali AM. Impacts of international sanctions on Iranian pharmaceutical market. Daru. 2013; 21(1):64. [DOI:10.1186/2008-2231-21-64] [PMID]

- Garfield R, Devin J, Fausey J. The health impact of economic sanctions. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1995; 72(2):454-69. [PMID]

- Abdollahi MR, Abolhassan Shirazi H. The direct impact of sanctions on health, physical and mental health. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences. 2021; 28(3):229-45. [Link]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Mohammadpur A. [Qualitative research method counter method2: The practical stages and procedures in qualitative methodology (Persian)]. Tehran: Sociologists Publications; 2013. [Link]

- Kalb R, Brown TR, Coote S, Costello K, Dalgas U, Garmon E, et al. Exercise and lifestyle physical activity recommendations for people with multiple sclerosis throughout the disease course. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2020; 26(12):1459-69. [DOI:10.1177/1352458520915629] [PMID]

- Kalb R, Holland N, Giesser B. Multiple sclerosis for dummies. Hoboken: Wiley; 2007. [Link]

- Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Ghafari S, Mohammadi E. [Exploring barriers of rehabilitation care in patients with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Nursing and Midwifery Journal. 2014; 11(11):863-74. [Link]

- Kheftan P, Gholami Jam F, Arshi M, Vameghi R, Khankeh HR, Fathi M. [Explaining the individual problems of women affected by Multiple sclerosis: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Journal of Jiroft University of Medical Sciences. 2017; 3(2):47-54. [Link]

- Mirmoeini P, Bayazi MH, Khalatbari J. [Comparing the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy and compassion focused therapy on worry severity and loneliness among the patients with multiple sclerosis (Persian)]. Internal Medicine Today. 2021; 27(4):534-49. [DOI:10.32598/hms.27.4.3426.1]

- Parsa M, Sabahi P, Mohammadifar MA. [The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment group therapy to improving the quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018; 10(1):21-8. [DOI:10.22075/jcp.2018.11686.1156]

- Potter KJ, Golijana-Moghaddam N, Evangelou N, Mhizha-Murira JR, das Nair R. Self-help acceptance and commitment therapy for carers of people with multiple sclerosis: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2021; 28(2):279-94. [DOI:10.1007/s10880-020-09711-x] [PMID]

- Anwar A, Malik M, Raees V, Anwar A. Role of mass media and public health communications in the covid-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2020; 12(9):e10453. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.10453]

- Alipour F, Arshi M, Ahmadi S, LeBeau R, Shaabani A, Ostadhashemi L. Psychosocial challenges and concerns of COVID-19: A qualitative study in Iran. Health. 2022; 26(6):702-19. [DOI:10.1177/1363459320976752] [PMID]

- Hejazi S, Peyman N, Tajfard M, Esmaily H. [The impact of education based on self-efficacy theory on health literacy, self-efficacy and self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2018; 5(4):296-303. [DOI:10.30699/acadpub.ijhehp.5.4.296]

- Pooryaghob M, Abdollahi F, Mobadery T, Haji Shabanha N, Bajalan Z. [Assesse the health literacy in multiple sclerosis patients (Persian)]. Journal of Health Literacy. 2018; 2(4):266-74. [DOI:10.29252/jhl.2.4.6]

- Dahham J, Rizk R, Kremer I, Evers S, Hiligsmann M. Economic burden of multiple sclerosis in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021; 39(7):789-807. [DOI:10.1007/s40273-021-01032-7] [PMID]

- Battaglia MA, Bezzini D, Cecchini I, Cordioli C, Fiorentino F, Manacorda T, et al. Patients with multiple sclerosis: A burden and cost of illness study. Journal of Neurology. 2022; 269(9):5127-35. [DOI:10.1007/s00415-022-11169-w] [PMID]

- Patel VP, Walker LA, Feinstein A. Revisiting cognitive reserve and cognition in multiple sclerosis: A closer look at depression. Multiple Sclerosis. 2018; 24(2):186-95. [DOI:10.1177/1352458517692887] [PMID]

- Mohr DC, Cox D. Multiple sclerosis: Empirical literature for the clinical health psychologist. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001; 57(4):479-99. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.1042] [PMID]

- Khankeh HR, Mohammadi R, Ahmadi F. [Barriers and facilitators of health care services at the time of natural disasters (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2005; 6(1):23-30. [Link]

- Payne M. Modern social work theory, fourth edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Link]

- Akbarialiabad H, Rastegar A, Bastani B. How sanctions have impacted Iranian healthcare sector: A brief review. Arch Iran Med. 2021; 24(1):58-63. [DOI:10.34172/aim.2021.09] [PMID]

- Gholamzad S, Saeidi N, Danesh S, Ranjbar H, Zarei M. [Analyzing the elderly’s quarantine-related experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic (Persian)]. Salmand. 2021; 16(1):30-45. [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.2083.3]

Type of article: Research |

Subject:

Qualitative

Received: 2024/06/28 | Accepted: 2025/01/5 | Published: 2025/07/9

Received: 2024/06/28 | Accepted: 2025/01/5 | Published: 2025/07/9

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |