Volume 10, Issue 3 (Spring 2025)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025, 10(3): 227-236 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Purnomo E, Hamid A Y S, Gayatri D, Setiawan A. Functions and Obstacles of Nurse Leadership in Disaster Management in West Sulawesi, Indonesia: A Qualitative Study. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025; 10 (3) :227-236

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-639-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-639-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia. , edipurnomo041077@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychiatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia.

3- Department of Nursing Basics and Basic Nursing, University Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia.

4- Department of Community Nursing, University Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia.

2- Department of Psychiatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia.

3- Department of Nursing Basics and Basic Nursing, University Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia.

4- Department of Community Nursing, University Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia.

Keywords: Disasters, Disaster planning, Disaster nursing, Earthquakes, Leadership, Qualitative research

Full-Text [PDF 497 kb]

(290 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1815 Views)

Full-Text: (400 Views)

Introduction

Nurses' role in preparing for and reacting to disasters has been extensively acknowledged [1, 2]. We must enhance the readiness of nurses to tackle disasters when they strike effectively. This gap in preparedness must be addressed to ensure better outcomes in crises [3]. Little attention has been paid to preparing nurse leaders for disaster preparedness, response, and recovery [4, 5, 6, 7]. Nurse leaders play a vital role in guiding and coordinating various emergency response responsibilities amidst critical situations due to disasters, both locally, regionally, and nationally [1, 4, 8]. Thus, to expand findings and develop capacity-building programs for nurse leadership and disaster risk management with relevant literature, input from disaster nursing experts and nurses' experiences during disasters is needed. These resources are critical to effectively empowering nursing leadership in disaster preparedness.

Indonesia is at the meeting point of four major tectonic plates: Eurasian, Indo-Australian, Philippine, and Pacific [9, 10]. This distinct location makes Indonesia particularly vulnerable to natural disasters [11, 12, 13]. Indonesia is a country vulnerable to disasters, making it the third most vulnerable country in the world [14, 15]. West Sulawesi Province is one of the provinces that has the potential to contribute to disaster events in Indonesia [9]. On January 15, 2021, a tectonic earthquake with a magnitude of 6.2 occurred [16]. This earthquake led to 105 fatalities, 3369 injuries, 89524 displaced people, and 7922 damaged buildings [17, 18].

Considering the health impacts of disasters, a comprehensive strategy to reduce disaster risk and losses is very important. It must involve all parties, especially healthcare providers [19], including nurses who interact directly with the community [12]. As health professionals, nurses represent one of the largest groups of healthcare providers [11, 19]. They work in health centers and are at the forefront of primary health services [12]. Given their essential role in the healthcare system, nurses should be able to respond well when disasters strike [13, 19–21].

Nursing leaders face obstacles in navigating situational uncertainty and the potential for large-scale disasters [2, 22]. This uncertainty requires leaders to be adaptable and develop contingency plans that can be quickly modified as the situation evolves [23]. Nurse leaders must have good problem-solving, decision-making, communication, and prioritization skills to plan, respond, and learn from critical events during disaster emergency response [2, 8, 24].

Leadership and management are different, but both have essential functions. Leadership and management are frequently used together as a single concept [25]. Disaster management is crucial to leadership, with nurse leaders describing nurses in leadership and management roles [2]. Successful leadership can mitigate the damage caused by a disastrous event, while poor leadership can worsen its effects [26]. Despite the critical importance of nursing leadership during disasters, few empirical studies have examined their specific roles.

This research is essential considering the crucial role of nurses when an earthquake occurs. They are the first to respond when a disaster occurs. In addition, nurses' role has contributed to reducing risks and losses due to catastrophe even though this is their first disaster experience. The management of disaster nursing management has not become a serious concern by stakeholders as a solution to overcome the current earthquake disaster problem. These findings can be the basis for policy formulation and the development of more effective training programs to increase the leadership capacity of nurses in responding to disasters. This research describes how nurse leaders implement disaster management functions in response to earthquake disasters.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Qualitative research methodology is conducted through a phenomenological approach, followed by content analysis [27]. Qualitative content analysis offers excellent flexibility in analyzing different data types, from text to visuals. As such, this method is beneficial for understanding the complex nuances of human experience and social problems [28, 29]. The method is best for generating knowledge, stating facts, and offering guidance to achieve this study's goals [30].

Participants and setting

This research was conducted in four health centers in West Sulawesi. This location was chosen as an area severely affected by the 2021 earthquake and was a primary health service center during the disaster. Nurses selected for this study were chosen using purposive sampling methods. The inclusion criteria were nurses who had direct involvement in the 2021 earthquake in West Sulawesi, those able to recount their experiences while delivering nursing care during the disaster, individuals with at least 5 years of experience at the health center, and those who were willing to take part in the research.

Data collection

We gathered valuable data by conducting focus group discussions (FGDs) and taking detailed field notes from March to July 2024. A research team created guidelines to examine nurses’ experiences in disaster management, human resource management, family roles and responsibilities, and communication and coordination barriers. The FGD was conducted on 32 health center nurses, divided into 4 groups of 8 people each. The decision to conduct the FGD on the four focus groups was based on consideration of data saturation and other relevant factors. Each group comprises a moderator and a note-taker to help things run smoothly and keep the conversation flowing. This setup encourages everyone to participate in discussions actively. We strive to establish a safe space for nurses to share their thoughts and feelings about their experiences in disaster leadership. This initiative will enhance our understanding of the complexities involved in the role of nurses during emergencies. Overall, these activities create a warm environment for lively discussions. Open-ended questions encouraged nurses to reflect and voice their ideas and experiences in dealing with barriers to leadership and disaster management. Researchers act as moderators and take field notes. These notes observe and record verbal behaviors, such as pauses, facial expressions, and actions, during FGD. Each FGD lasted between 60 and 90 minutes, or until critical insights emerged. The entire process was captured through audio and video recordings, ensuring valuable information was preserved for further analysis. The FGD included four main questions: (i) What is your experience related to management during disasters?

(ii) How is human resource management during disasters?

(iii) How do you balance roles and responsibilities during disasters?

(iv) What obstacles do you experience when coordinating and communicating across sectors during disaster management?

Data Analysis

This study adopts a qualitative content analysis approach to explore the deep meaning of the data [31]. To ensure a thorough understanding of participant perspectives, FGDs were digitally recorded, transcribed, coded, and analyzed concurrently throughout the data collection process. This approach guarantees that valuable insights are captured and utilized effectively. The lead author identified categories, which were verified for consistency by two co-authors. Statements supporting each category were discussed until a consensus was reached. All authors had experience in disaster management, helping them identify research gaps. The researchers used reflective notebooks to minimize personal bias and consulted disaster experts.

Trustworthiness

We used four criteria as a reference to test reliability and increase confidence in our findings [32]. Data credibility was achieved by returning the results of the FGD interview transcripts to participants. The goal is to ensure the accuracy of the data and interpretation by the participant experience. To control data dependability, researchers conduct data transcripts and data analysis in a thorough and structured manner so that other independent researchers can replicate the data interpretation results and produce similar conclusions. The research team conducts a peer check to encode and categorize the research results to ensure data conformity. Then, the code and categories that have been created are evaluated by the researchers. If there is a disagreement regarding specific codes and categories, further discussions will be held to clarify the differences and reach a mutual agreement. The researcher carried out transferability by providing the results of data transcripts to nurses with the same criteria at other health centers so they could read and agree on the findings.

Results

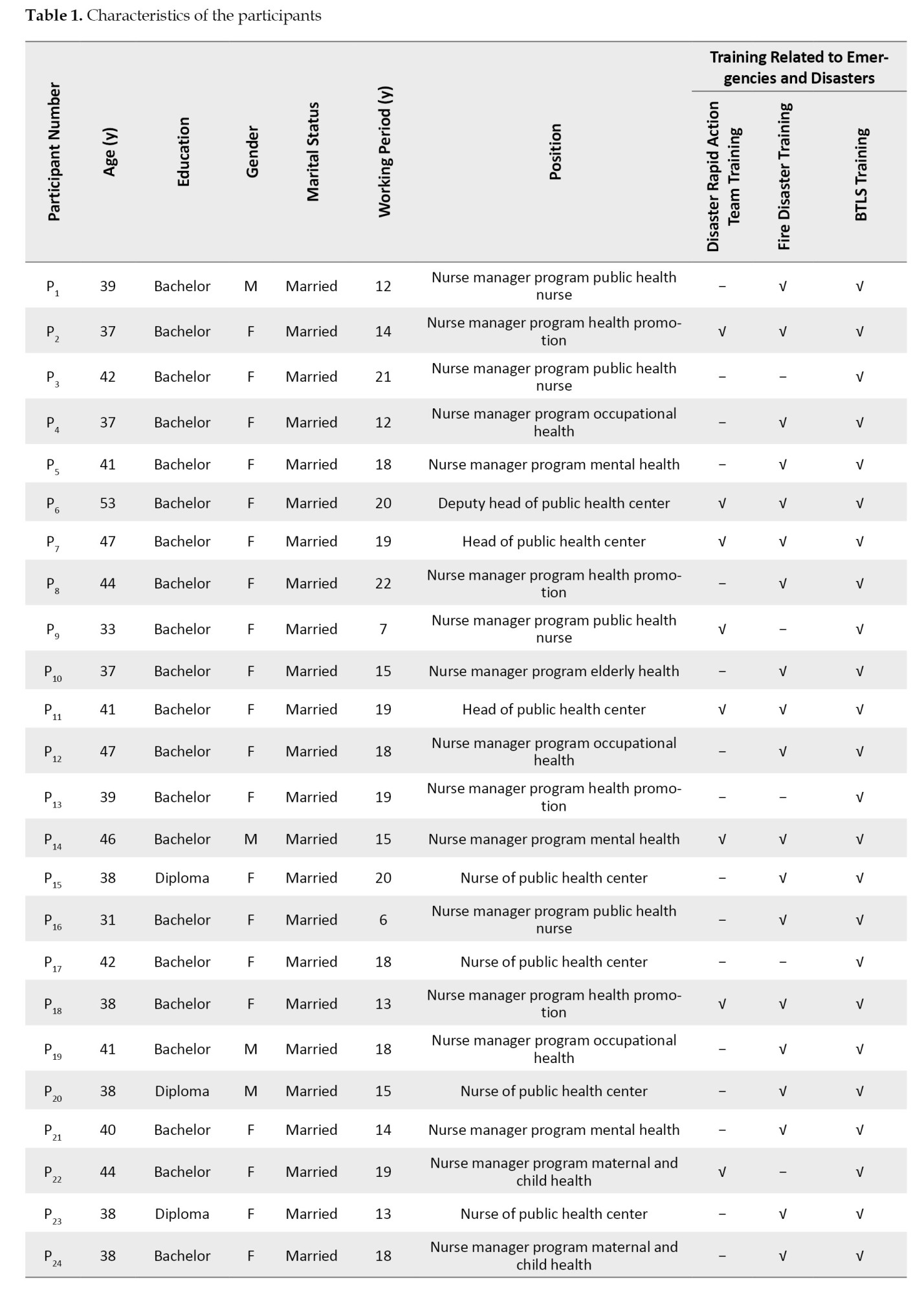

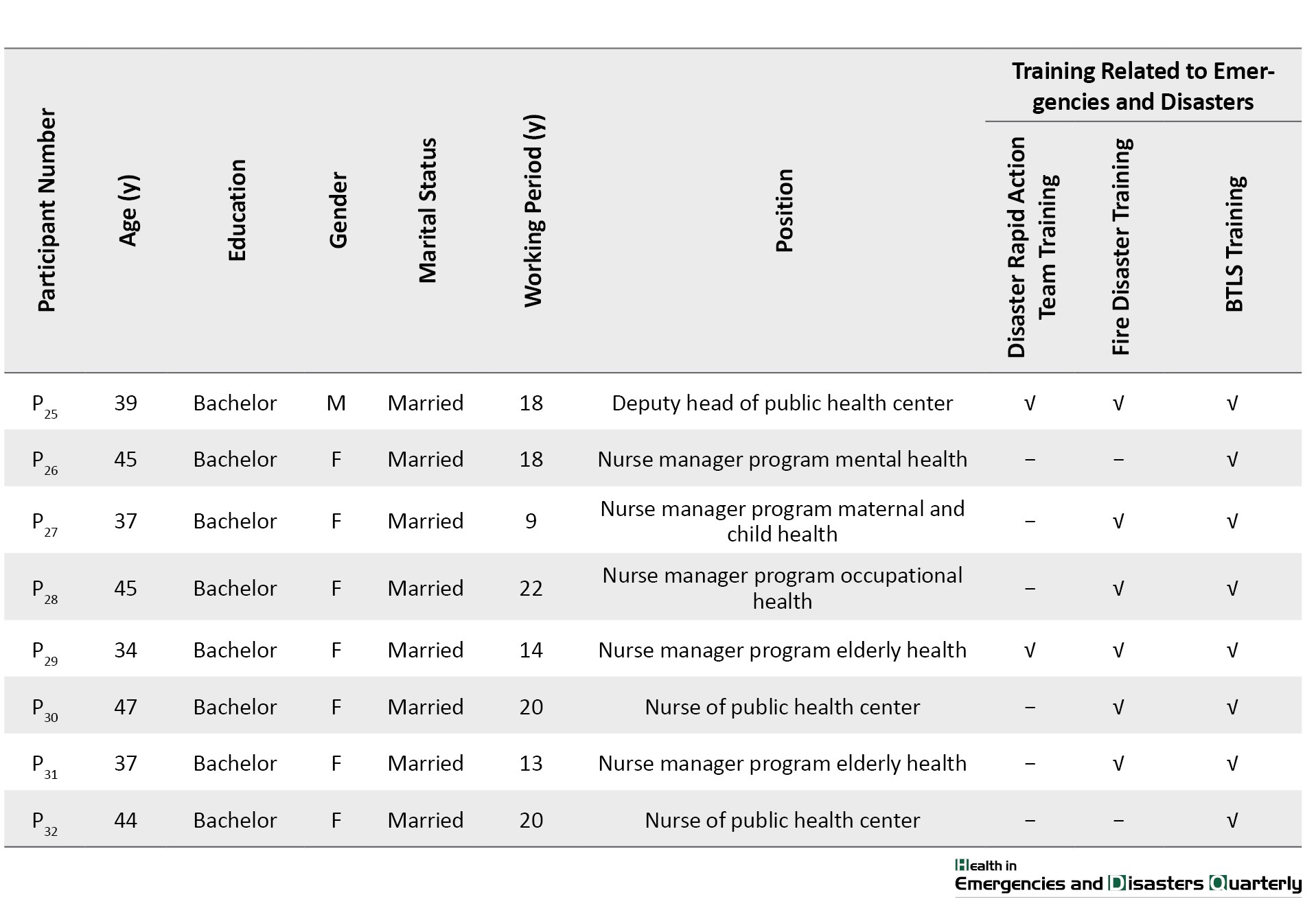

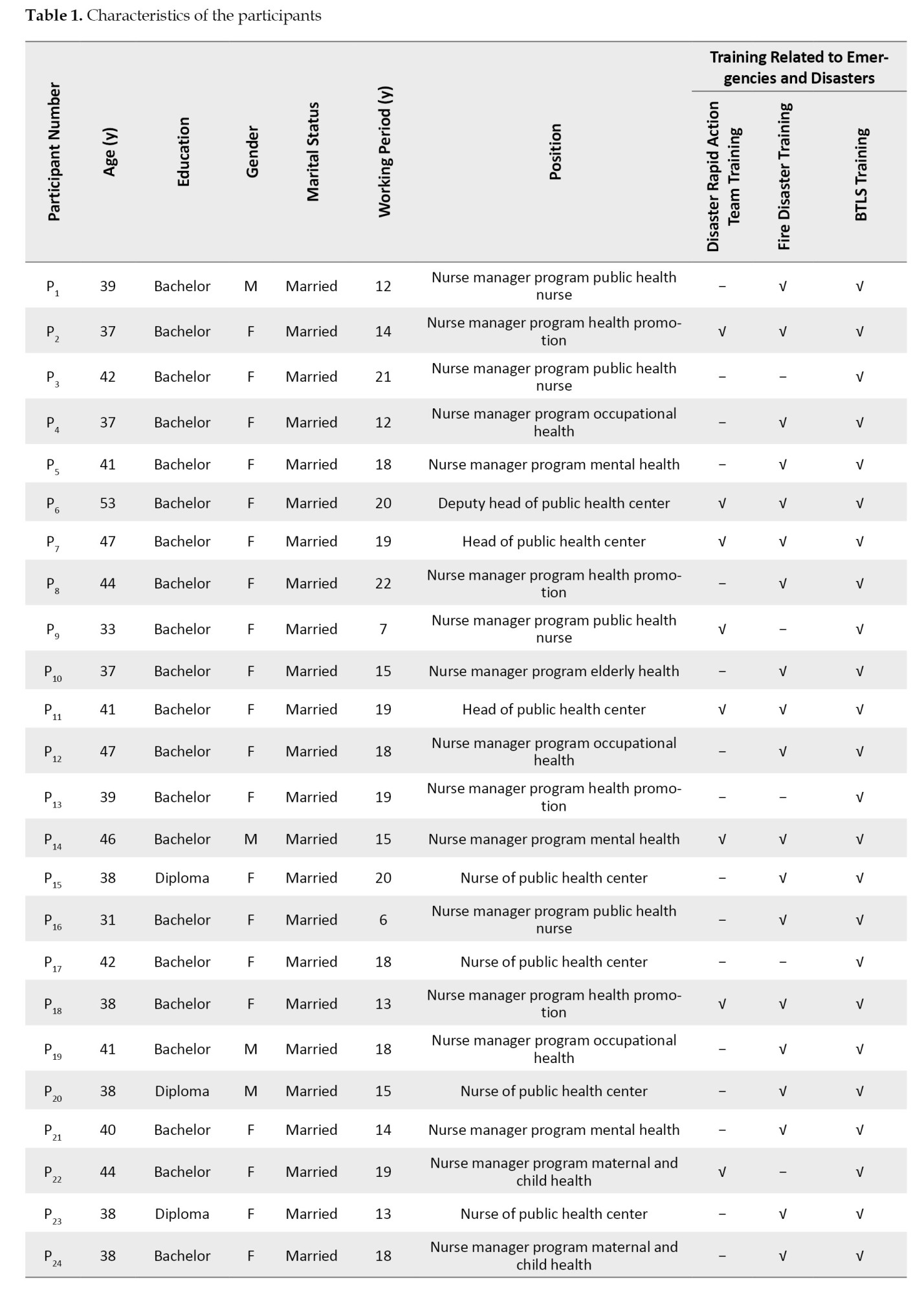

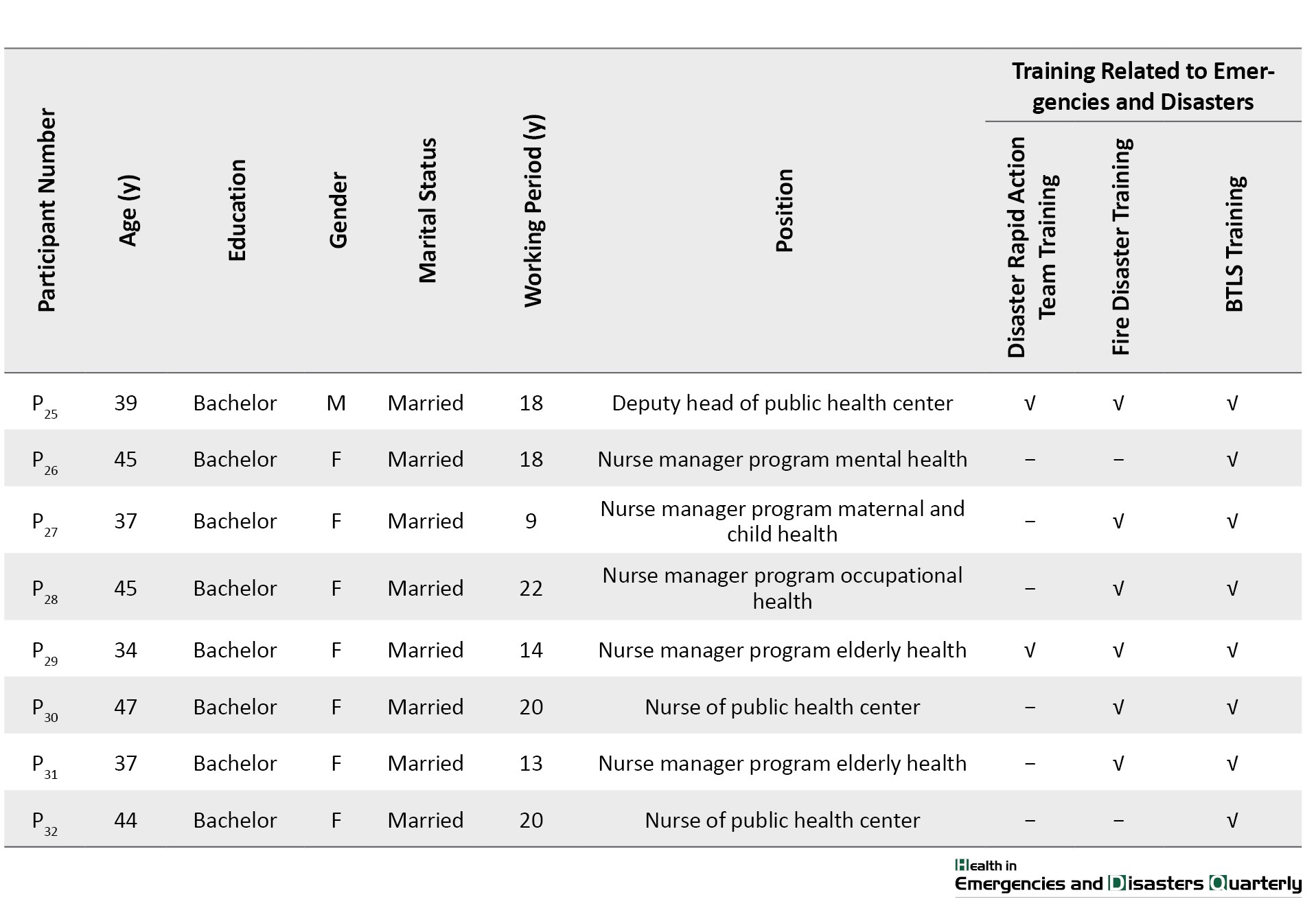

The characteristics of nurse participants were as follows: Their median age was 40.59 years (40.59±4.69), the majority were female (84.37%), all participants were married, and their highest education was bachelor’s (90.62%), their Mean±SD length of employment was 16.22±4.12 years. The participants’ positions consisted of 2 heads of health centers (6.25%), 2 deputy heads of health centers (6.25%), 28 nurses in charge of the program (87.5%), and 6 nurses (18.75). Regarding the history of disaster training, all participated in basic trauma live support (BTLS) training, 10(31.3%) in disaster rapid action team training, and 25(78.1%) in fire disaster training (Table 1).

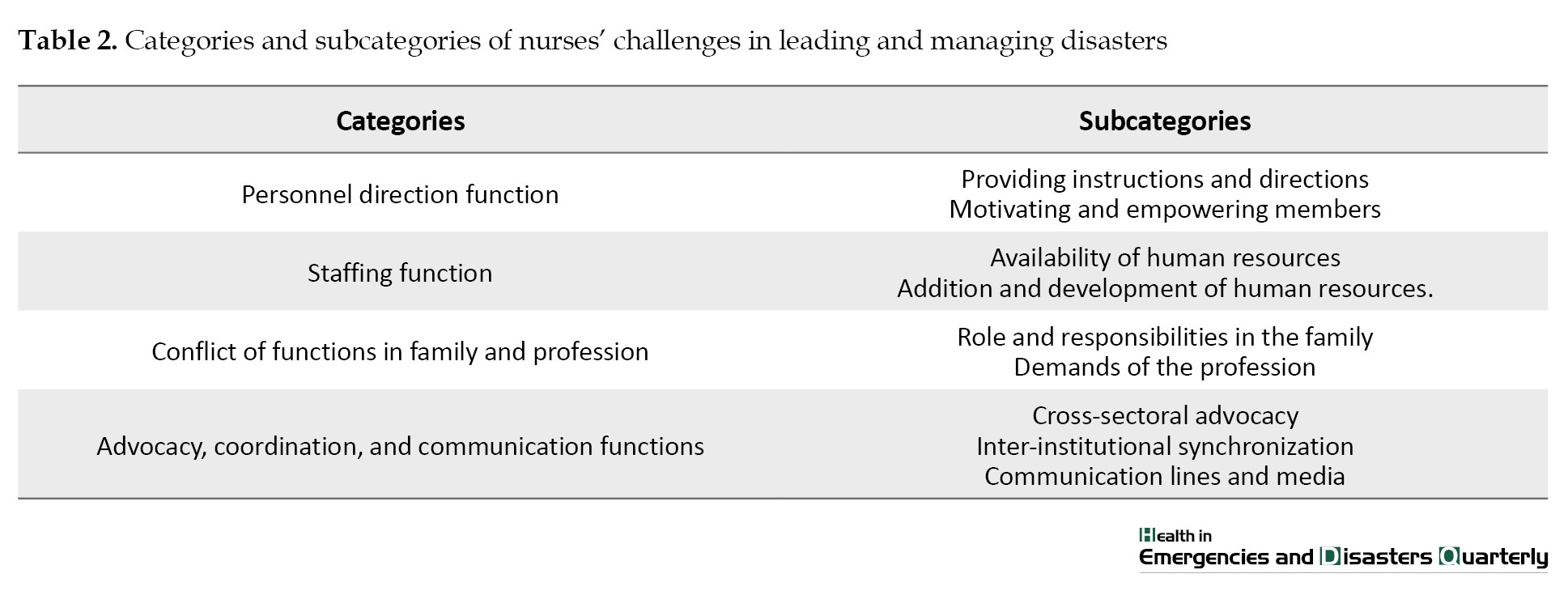

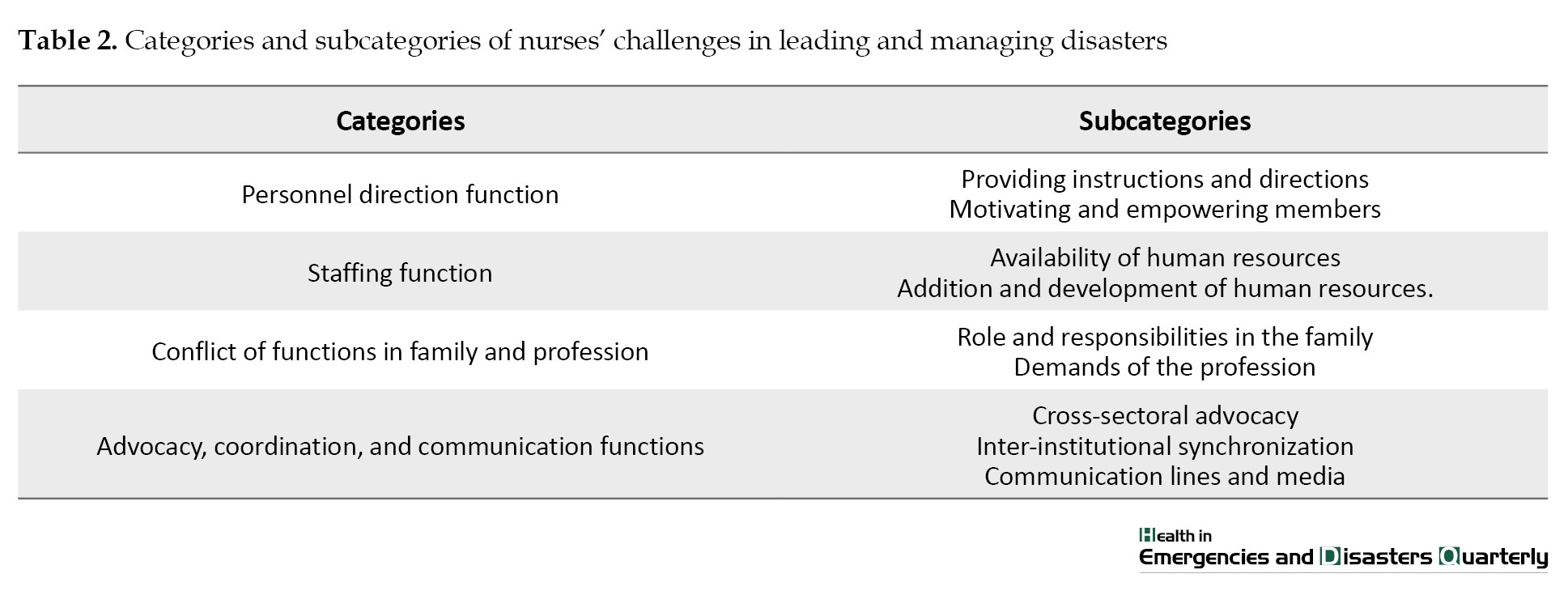

Experiences regarding challenges in nursing leadership and disaster management among nurses were divided into 4 categories: 1) Personnel direction function, 2) Staffing function, 3) Conflict of functions in family and profession, and 4) Advocacy, coordination, and communication functions (Table 2).

Personnel direction function

Based on the participants’ experience in this study, the personnel direction function is vital in disaster emergency response situations. It can ensure the health team works optimally and encourage team participation in decision-making. With proper personnel direction, the entire potential of the team can be optimally utilized to handle disaster victims. This category has two subcategories: providing instructions and directions and motivating and empowering members.

Providing instructions and directions

According to the participants, providing instructions, immediately opening posts, having to open services, and posting schedules are some of the essential functions of nurses in directing personnel during disaster emergency response. About this, the following sentences were stated:

“Instructing all health center staff to resume providing health services” (Participant [P] 1), “Immediately open posts at the health center, health center pharmacists issue all medicines needed for health services” (P3), “The morning after the earthquake my husband and I went to the health center and had to open health center services and we anticipated victims due to the disaster” (P11), “Daily reports must be made and must attend according to the roster at several post points” (P14).

Motivating and empowering members

Some participants said that they took the initiative in handling victims, proposing simplified administration and the need for expertise in leading and managing members through the participants’ statements below:

“I took the initiative to invite other friends to come to the health center” (P5), “Our area was more affected, proposing simplified administrative logistics and infrastructure for faster distribution” (P8), “The need for leadership in managing all members, yesterday it was overwhelmed because dealing with earthquake disasters with covid 19” (P13).

Staffing function

Staffing or organizing staff is one of the critical leadership functions in disaster management. Nurses, as leaders, must be able to compile and organize the staff needed to handle disaster victims effectively. This category has two subcategories: the availability of human resources and the addition and development of human resources.

Availability of human resources

The number of human resources needed is often not proportional to the scale of the disaster. Some participants conveyed inadequate human resource availability through the participants’ statements below:

“The number of health workers who could come was around 20% of the total health center staff. The rest were far away in refugee camps” (P3), “The heavier the tasks in the field with limited staff who could come to the health center” (P15). “At that time, there were still frequent aftershocks; many patients came and were angry to be treated first, and no additional staff could come (P17). “We lack staff because they are divided to go into the field and keep posts at disaster sites” (P10).

Addition and development of human resources

In such emergencies, the presence of volunteers from various regions is very much needed to assist in the evacuation and treatment of victims, according to the participants’ statements below:

“Joined volunteers from the HIPGABI Palu one day after the earthquake to help the health center post” (P19), “The next day, there were already volunteers from Palu who had arrived; the community really needed volunteer assistance” (P5).

Conflict of functions in family and profession

Role conflict between family and professional functions often occurs in nurses assigned to assist in handling disaster victims outside their city or region. This category has two subcategories: the role and responsibilities in the family and the profession’s demands.

Role and responsibilities in the family

Ensuring the family is in a safe condition before departing for duty. If necessary, evacuate the family to a safer place, as in the participants’ statements below:

“I am also a West Sulawesi volunteer who has not moved because I am taking care of a family that cannot be left behind and the community also needs us” (P20), “It happened that I was taking care of a family from a village who was sick” (P30), “At that time I did not participate in handling the disaster because of a young child who could not be left behind and taking care of a sick parent” (P32).

Demands of the profession

Nurses often face a dilemma when having to choose between staying with family or going to help victims at the disaster site, as in the participants’ statements below:

“Asking permission from parents and husband that we are safe, this is my nursing profession to return to Mamuju to help disaster services at the post” (P25). “I wanted to come down, but my husband didn’t allow it, and I had to take care of my parents who were still sick” (P19).

Advocacy, coordination, and communication functions

The functions of advocacy, coordination, and communication are important aspects of nursing leadership during disasters but often become obstacles. This category has three subcategories: cross-sectoral advocacy, inter-institutional synchronization, and communication lines and media.

Cross-sectoral advocacy

Intensive advocacy across all sectors between government and society is needed to ensure rapid and adequate assistance for disaster victims, as in the following participant statements:

“Involving all related sectors in the distribution of disaster logistics and basic needs for refugees” (P23). “At the Regional Police, for highland areas, there are recommendations from the government regarding safe refugee locations” (P18).

Inter-institutional synchronization

Poor cross-sectoral communication and coordination between various institutions when a disaster occurs impacts the hampered synchronization in channeling aid and relief to victims, as in the following participant statements:

“Good cross-sectoral communication facilitates assisting disaster victims” (P4). “The absence of effective coordination with local government leads to significant delays; many individuals are left uncertain about where to seek assistance” (P15).

Communication lines and media

Disrupted communication due to congested telephone and internet networks during large-scale disasters directly impacts the difficult coordination of victim handling between related parties, as in the following participant statements:

“Lack of communication with the regional government that forced us to open posts outside the area even though our area was more affected” (P11). “Before the network went out, there was an appeal from BMKG [Badan Meteorologi, Klimatologi dan Geofisika] for the public to be vigilant” (P20), “A lot of unclear information circulated among the public post-earthquake” (P25). “During a disaster emergency, we had to take care of administration to request assistance in the form of tents and health needs to related agencies” (P30).

Discussion

The main findings obtained by the researcher regarding the functions and obstacles of nurse leadership in disaster management include the function of personnel direction, personnel function, functional conflict in the family and profession, advocacy, coordination, and communication functions. This study's findings support previous research indicating that nursing leadership and disaster management are crucial for disaster preparedness and response [6, 8, 33]. In line with Thrwi et al., nurse leaders face many challenges in disaster response, including uncertainty, scarcity of resources, communication barriers, psychological stress, and complexity of interprofessional collaboration [22].

The present study highlights that nurses face obstacles in directing personnel functions, including giving instructions, directing, motivating, and empowering team members in emergency disaster situations. According to Madhyvadany and Panboli, the directing function is considered the most vital management function in achieving organizational goals because it provides clear instructions and focuses the efforts of all team members to implement plans and policies effectively [34]. However, investing in human resources and supporting health workers during critical phases is essential to enhance leadership effectiveness, as their exhaustion can impact results [35]. Therefore, strong leadership is needed to foster a culture of responsibility, motivate staff engagement, and encourage them to take the initiative according to their respective capacities [36].

This study found that nurses face difficulties in carrying out staffing functions, including the availability of human resources that are not comparable to the needs and scale of disasters and the need for additional development of human resources for proper disaster management. According to several studies, the shortage of nursing staff during disaster emergency response is a common problem because many nurses become victims or are affected by disasters, so they cannot work; this was found in studies in various countries [37, 38]. Therefore, volunteers are needed to assist in evacuation and victim care. However, organizing volunteers and their duties needs to be done correctly so that the division of labor is effective. Organizing human resources is vital for nurse leaders to respond adequately during disasters [39].

Another critical finding of this study was the problem of conflicts of functions in family and profession. These factors are the conflicts between the roles of nurses and their family responsibilities and the profession's demands when assigned to disaster areas. Many nurses struggle to balance their health with patient care, family responsibilities, and professional commitments during disasters [30, 40]. Enhancing financial and psychological support for nurses is crucial to reducing moral distress and preventing burnout. This focus can improve talent retention and ensure quality patient care, fostering a healthier work environment and encouraging nurses to stay in their roles [41].

Participants in the study reported experiencing more obstacles in advocacy, coordination, and communication functions for nursing leadership during disasters, including cross-sectoral advocacy, inter-institutional synchronization, and communication lines and media. According to several studies, intensive cross-sectoral advocacy is needed to ensure a rapid and adequate response [42]. However, unprepared response coordination can often result in wasteful utilization of already scarce time and resources [40, 43]. Effective and reliable communication is the foundation of disaster management. Therefore, nurse leaders must build a resilient communication system that can operate even when infrastructure is disrupted to coordinate response properly [22, 44].

Nurse leadership plays an essential role in disaster management but faces several obstacles in carrying out their functions. To overcome this problem, it is necessary to increase the leadership capacity of nurses through special training in disaster management so that they are better prepared to lead their teams. In addition, it is necessary to prepare a database of trained nurses and volunteers who can be mobilized during disasters, as well as psychosocial and financial support for nurses. Cross-sectoral coordination needs to be improved through regular simulations and joint exercises. Building a robust communication system that integrates various channels and technologies is also essential. With these steps, it is hoped that nurse leadership can perform its vital role more optimally in disaster management.

Conclusion

This study identified several obstacles nurses face in leadership and disaster management during the earthquake emergency response, including personnel direction, staffing, balancing family and professional roles, and coordination, communication, and advocacy functions. Limited human resources, unclear instructions, poor inter-agency coordination, and communication barriers affected nursing leadership and coordination during the disaster. These findings highlight the importance of improving nurse competencies in disaster management through training and simulation. Nurse leaders must have crisis decision-making skills, resource management, effective communication, and coping strategies. Improving coordination and collaboration between health institutions and other related agencies must also be a priority to optimize disaster response. Further research is needed to develop training models and nursing and government policy recommendations to empower nurse leaders during disasters.

Limitations and future study

The study highlights limitations and proposes future research to enhance our understanding of the topic. First, the study was limited to nurses from 4 health centers in West Sulawesi, so the experiences and challenges may differ from those in other areas affected by the earthquake. Therefore, a broader study involving more participants from affected and non-affected earthquake regions is necessary to obtain a more comprehensive picture. Second, the participants in this study are primarily women, so they do not represent the experience of male nurses. Further studies are needed with a balanced proportion of male and female participants. Finally, the data were collected only through FGD, so there was a possibility of not fully exploring the individual experiences of each participant. It is necessary to consider in-depth interview methods to complement the data.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has official approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia (Code: Nu.077/UN2.F12.D121/PPM.00.02/2024). Before participating in the study, the participants were given complete information about the purpose and methodology of the research. The researchers then asked the participants to sign an informed consent form before participating in the study. The confidentiality of the participant’s identity was guaranteed, and the participant was free to withdraw. Their comfort and trust were our top priorities.

Funding

This paper is based on Edi Purnomo’s approved PhD dissertation from the Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia. This research was conducted without the use of any funding.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Edi Purnomo and Achir Yani S. Hamid; Methodology, data analysis, and investigation: Dewi Gayatri and Edi Purnomo; Data collection, and writing: Edi Purnomo and Agus Setiawan; Funding administration: Edi Purnomo; Final approval : All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors were dedicated to transparency and declared no competing interests or conflicts related to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Mamuju Health Polytechnic Indonesia for supporting the primary author throughout the research.

References

Nurses' role in preparing for and reacting to disasters has been extensively acknowledged [1, 2]. We must enhance the readiness of nurses to tackle disasters when they strike effectively. This gap in preparedness must be addressed to ensure better outcomes in crises [3]. Little attention has been paid to preparing nurse leaders for disaster preparedness, response, and recovery [4, 5, 6, 7]. Nurse leaders play a vital role in guiding and coordinating various emergency response responsibilities amidst critical situations due to disasters, both locally, regionally, and nationally [1, 4, 8]. Thus, to expand findings and develop capacity-building programs for nurse leadership and disaster risk management with relevant literature, input from disaster nursing experts and nurses' experiences during disasters is needed. These resources are critical to effectively empowering nursing leadership in disaster preparedness.

Indonesia is at the meeting point of four major tectonic plates: Eurasian, Indo-Australian, Philippine, and Pacific [9, 10]. This distinct location makes Indonesia particularly vulnerable to natural disasters [11, 12, 13]. Indonesia is a country vulnerable to disasters, making it the third most vulnerable country in the world [14, 15]. West Sulawesi Province is one of the provinces that has the potential to contribute to disaster events in Indonesia [9]. On January 15, 2021, a tectonic earthquake with a magnitude of 6.2 occurred [16]. This earthquake led to 105 fatalities, 3369 injuries, 89524 displaced people, and 7922 damaged buildings [17, 18].

Considering the health impacts of disasters, a comprehensive strategy to reduce disaster risk and losses is very important. It must involve all parties, especially healthcare providers [19], including nurses who interact directly with the community [12]. As health professionals, nurses represent one of the largest groups of healthcare providers [11, 19]. They work in health centers and are at the forefront of primary health services [12]. Given their essential role in the healthcare system, nurses should be able to respond well when disasters strike [13, 19–21].

Nursing leaders face obstacles in navigating situational uncertainty and the potential for large-scale disasters [2, 22]. This uncertainty requires leaders to be adaptable and develop contingency plans that can be quickly modified as the situation evolves [23]. Nurse leaders must have good problem-solving, decision-making, communication, and prioritization skills to plan, respond, and learn from critical events during disaster emergency response [2, 8, 24].

Leadership and management are different, but both have essential functions. Leadership and management are frequently used together as a single concept [25]. Disaster management is crucial to leadership, with nurse leaders describing nurses in leadership and management roles [2]. Successful leadership can mitigate the damage caused by a disastrous event, while poor leadership can worsen its effects [26]. Despite the critical importance of nursing leadership during disasters, few empirical studies have examined their specific roles.

This research is essential considering the crucial role of nurses when an earthquake occurs. They are the first to respond when a disaster occurs. In addition, nurses' role has contributed to reducing risks and losses due to catastrophe even though this is their first disaster experience. The management of disaster nursing management has not become a serious concern by stakeholders as a solution to overcome the current earthquake disaster problem. These findings can be the basis for policy formulation and the development of more effective training programs to increase the leadership capacity of nurses in responding to disasters. This research describes how nurse leaders implement disaster management functions in response to earthquake disasters.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Qualitative research methodology is conducted through a phenomenological approach, followed by content analysis [27]. Qualitative content analysis offers excellent flexibility in analyzing different data types, from text to visuals. As such, this method is beneficial for understanding the complex nuances of human experience and social problems [28, 29]. The method is best for generating knowledge, stating facts, and offering guidance to achieve this study's goals [30].

Participants and setting

This research was conducted in four health centers in West Sulawesi. This location was chosen as an area severely affected by the 2021 earthquake and was a primary health service center during the disaster. Nurses selected for this study were chosen using purposive sampling methods. The inclusion criteria were nurses who had direct involvement in the 2021 earthquake in West Sulawesi, those able to recount their experiences while delivering nursing care during the disaster, individuals with at least 5 years of experience at the health center, and those who were willing to take part in the research.

Data collection

We gathered valuable data by conducting focus group discussions (FGDs) and taking detailed field notes from March to July 2024. A research team created guidelines to examine nurses’ experiences in disaster management, human resource management, family roles and responsibilities, and communication and coordination barriers. The FGD was conducted on 32 health center nurses, divided into 4 groups of 8 people each. The decision to conduct the FGD on the four focus groups was based on consideration of data saturation and other relevant factors. Each group comprises a moderator and a note-taker to help things run smoothly and keep the conversation flowing. This setup encourages everyone to participate in discussions actively. We strive to establish a safe space for nurses to share their thoughts and feelings about their experiences in disaster leadership. This initiative will enhance our understanding of the complexities involved in the role of nurses during emergencies. Overall, these activities create a warm environment for lively discussions. Open-ended questions encouraged nurses to reflect and voice their ideas and experiences in dealing with barriers to leadership and disaster management. Researchers act as moderators and take field notes. These notes observe and record verbal behaviors, such as pauses, facial expressions, and actions, during FGD. Each FGD lasted between 60 and 90 minutes, or until critical insights emerged. The entire process was captured through audio and video recordings, ensuring valuable information was preserved for further analysis. The FGD included four main questions: (i) What is your experience related to management during disasters?

(ii) How is human resource management during disasters?

(iii) How do you balance roles and responsibilities during disasters?

(iv) What obstacles do you experience when coordinating and communicating across sectors during disaster management?

Data Analysis

This study adopts a qualitative content analysis approach to explore the deep meaning of the data [31]. To ensure a thorough understanding of participant perspectives, FGDs were digitally recorded, transcribed, coded, and analyzed concurrently throughout the data collection process. This approach guarantees that valuable insights are captured and utilized effectively. The lead author identified categories, which were verified for consistency by two co-authors. Statements supporting each category were discussed until a consensus was reached. All authors had experience in disaster management, helping them identify research gaps. The researchers used reflective notebooks to minimize personal bias and consulted disaster experts.

Trustworthiness

We used four criteria as a reference to test reliability and increase confidence in our findings [32]. Data credibility was achieved by returning the results of the FGD interview transcripts to participants. The goal is to ensure the accuracy of the data and interpretation by the participant experience. To control data dependability, researchers conduct data transcripts and data analysis in a thorough and structured manner so that other independent researchers can replicate the data interpretation results and produce similar conclusions. The research team conducts a peer check to encode and categorize the research results to ensure data conformity. Then, the code and categories that have been created are evaluated by the researchers. If there is a disagreement regarding specific codes and categories, further discussions will be held to clarify the differences and reach a mutual agreement. The researcher carried out transferability by providing the results of data transcripts to nurses with the same criteria at other health centers so they could read and agree on the findings.

Results

The characteristics of nurse participants were as follows: Their median age was 40.59 years (40.59±4.69), the majority were female (84.37%), all participants were married, and their highest education was bachelor’s (90.62%), their Mean±SD length of employment was 16.22±4.12 years. The participants’ positions consisted of 2 heads of health centers (6.25%), 2 deputy heads of health centers (6.25%), 28 nurses in charge of the program (87.5%), and 6 nurses (18.75). Regarding the history of disaster training, all participated in basic trauma live support (BTLS) training, 10(31.3%) in disaster rapid action team training, and 25(78.1%) in fire disaster training (Table 1).

Experiences regarding challenges in nursing leadership and disaster management among nurses were divided into 4 categories: 1) Personnel direction function, 2) Staffing function, 3) Conflict of functions in family and profession, and 4) Advocacy, coordination, and communication functions (Table 2).

Personnel direction function

Based on the participants’ experience in this study, the personnel direction function is vital in disaster emergency response situations. It can ensure the health team works optimally and encourage team participation in decision-making. With proper personnel direction, the entire potential of the team can be optimally utilized to handle disaster victims. This category has two subcategories: providing instructions and directions and motivating and empowering members.

Providing instructions and directions

According to the participants, providing instructions, immediately opening posts, having to open services, and posting schedules are some of the essential functions of nurses in directing personnel during disaster emergency response. About this, the following sentences were stated:

“Instructing all health center staff to resume providing health services” (Participant [P] 1), “Immediately open posts at the health center, health center pharmacists issue all medicines needed for health services” (P3), “The morning after the earthquake my husband and I went to the health center and had to open health center services and we anticipated victims due to the disaster” (P11), “Daily reports must be made and must attend according to the roster at several post points” (P14).

Motivating and empowering members

Some participants said that they took the initiative in handling victims, proposing simplified administration and the need for expertise in leading and managing members through the participants’ statements below:

“I took the initiative to invite other friends to come to the health center” (P5), “Our area was more affected, proposing simplified administrative logistics and infrastructure for faster distribution” (P8), “The need for leadership in managing all members, yesterday it was overwhelmed because dealing with earthquake disasters with covid 19” (P13).

Staffing function

Staffing or organizing staff is one of the critical leadership functions in disaster management. Nurses, as leaders, must be able to compile and organize the staff needed to handle disaster victims effectively. This category has two subcategories: the availability of human resources and the addition and development of human resources.

Availability of human resources

The number of human resources needed is often not proportional to the scale of the disaster. Some participants conveyed inadequate human resource availability through the participants’ statements below:

“The number of health workers who could come was around 20% of the total health center staff. The rest were far away in refugee camps” (P3), “The heavier the tasks in the field with limited staff who could come to the health center” (P15). “At that time, there were still frequent aftershocks; many patients came and were angry to be treated first, and no additional staff could come (P17). “We lack staff because they are divided to go into the field and keep posts at disaster sites” (P10).

Addition and development of human resources

In such emergencies, the presence of volunteers from various regions is very much needed to assist in the evacuation and treatment of victims, according to the participants’ statements below:

“Joined volunteers from the HIPGABI Palu one day after the earthquake to help the health center post” (P19), “The next day, there were already volunteers from Palu who had arrived; the community really needed volunteer assistance” (P5).

Conflict of functions in family and profession

Role conflict between family and professional functions often occurs in nurses assigned to assist in handling disaster victims outside their city or region. This category has two subcategories: the role and responsibilities in the family and the profession’s demands.

Role and responsibilities in the family

Ensuring the family is in a safe condition before departing for duty. If necessary, evacuate the family to a safer place, as in the participants’ statements below:

“I am also a West Sulawesi volunteer who has not moved because I am taking care of a family that cannot be left behind and the community also needs us” (P20), “It happened that I was taking care of a family from a village who was sick” (P30), “At that time I did not participate in handling the disaster because of a young child who could not be left behind and taking care of a sick parent” (P32).

Demands of the profession

Nurses often face a dilemma when having to choose between staying with family or going to help victims at the disaster site, as in the participants’ statements below:

“Asking permission from parents and husband that we are safe, this is my nursing profession to return to Mamuju to help disaster services at the post” (P25). “I wanted to come down, but my husband didn’t allow it, and I had to take care of my parents who were still sick” (P19).

Advocacy, coordination, and communication functions

The functions of advocacy, coordination, and communication are important aspects of nursing leadership during disasters but often become obstacles. This category has three subcategories: cross-sectoral advocacy, inter-institutional synchronization, and communication lines and media.

Cross-sectoral advocacy

Intensive advocacy across all sectors between government and society is needed to ensure rapid and adequate assistance for disaster victims, as in the following participant statements:

“Involving all related sectors in the distribution of disaster logistics and basic needs for refugees” (P23). “At the Regional Police, for highland areas, there are recommendations from the government regarding safe refugee locations” (P18).

Inter-institutional synchronization

Poor cross-sectoral communication and coordination between various institutions when a disaster occurs impacts the hampered synchronization in channeling aid and relief to victims, as in the following participant statements:

“Good cross-sectoral communication facilitates assisting disaster victims” (P4). “The absence of effective coordination with local government leads to significant delays; many individuals are left uncertain about where to seek assistance” (P15).

Communication lines and media

Disrupted communication due to congested telephone and internet networks during large-scale disasters directly impacts the difficult coordination of victim handling between related parties, as in the following participant statements:

“Lack of communication with the regional government that forced us to open posts outside the area even though our area was more affected” (P11). “Before the network went out, there was an appeal from BMKG [Badan Meteorologi, Klimatologi dan Geofisika] for the public to be vigilant” (P20), “A lot of unclear information circulated among the public post-earthquake” (P25). “During a disaster emergency, we had to take care of administration to request assistance in the form of tents and health needs to related agencies” (P30).

Discussion

The main findings obtained by the researcher regarding the functions and obstacles of nurse leadership in disaster management include the function of personnel direction, personnel function, functional conflict in the family and profession, advocacy, coordination, and communication functions. This study's findings support previous research indicating that nursing leadership and disaster management are crucial for disaster preparedness and response [6, 8, 33]. In line with Thrwi et al., nurse leaders face many challenges in disaster response, including uncertainty, scarcity of resources, communication barriers, psychological stress, and complexity of interprofessional collaboration [22].

The present study highlights that nurses face obstacles in directing personnel functions, including giving instructions, directing, motivating, and empowering team members in emergency disaster situations. According to Madhyvadany and Panboli, the directing function is considered the most vital management function in achieving organizational goals because it provides clear instructions and focuses the efforts of all team members to implement plans and policies effectively [34]. However, investing in human resources and supporting health workers during critical phases is essential to enhance leadership effectiveness, as their exhaustion can impact results [35]. Therefore, strong leadership is needed to foster a culture of responsibility, motivate staff engagement, and encourage them to take the initiative according to their respective capacities [36].

This study found that nurses face difficulties in carrying out staffing functions, including the availability of human resources that are not comparable to the needs and scale of disasters and the need for additional development of human resources for proper disaster management. According to several studies, the shortage of nursing staff during disaster emergency response is a common problem because many nurses become victims or are affected by disasters, so they cannot work; this was found in studies in various countries [37, 38]. Therefore, volunteers are needed to assist in evacuation and victim care. However, organizing volunteers and their duties needs to be done correctly so that the division of labor is effective. Organizing human resources is vital for nurse leaders to respond adequately during disasters [39].

Another critical finding of this study was the problem of conflicts of functions in family and profession. These factors are the conflicts between the roles of nurses and their family responsibilities and the profession's demands when assigned to disaster areas. Many nurses struggle to balance their health with patient care, family responsibilities, and professional commitments during disasters [30, 40]. Enhancing financial and psychological support for nurses is crucial to reducing moral distress and preventing burnout. This focus can improve talent retention and ensure quality patient care, fostering a healthier work environment and encouraging nurses to stay in their roles [41].

Participants in the study reported experiencing more obstacles in advocacy, coordination, and communication functions for nursing leadership during disasters, including cross-sectoral advocacy, inter-institutional synchronization, and communication lines and media. According to several studies, intensive cross-sectoral advocacy is needed to ensure a rapid and adequate response [42]. However, unprepared response coordination can often result in wasteful utilization of already scarce time and resources [40, 43]. Effective and reliable communication is the foundation of disaster management. Therefore, nurse leaders must build a resilient communication system that can operate even when infrastructure is disrupted to coordinate response properly [22, 44].

Nurse leadership plays an essential role in disaster management but faces several obstacles in carrying out their functions. To overcome this problem, it is necessary to increase the leadership capacity of nurses through special training in disaster management so that they are better prepared to lead their teams. In addition, it is necessary to prepare a database of trained nurses and volunteers who can be mobilized during disasters, as well as psychosocial and financial support for nurses. Cross-sectoral coordination needs to be improved through regular simulations and joint exercises. Building a robust communication system that integrates various channels and technologies is also essential. With these steps, it is hoped that nurse leadership can perform its vital role more optimally in disaster management.

Conclusion

This study identified several obstacles nurses face in leadership and disaster management during the earthquake emergency response, including personnel direction, staffing, balancing family and professional roles, and coordination, communication, and advocacy functions. Limited human resources, unclear instructions, poor inter-agency coordination, and communication barriers affected nursing leadership and coordination during the disaster. These findings highlight the importance of improving nurse competencies in disaster management through training and simulation. Nurse leaders must have crisis decision-making skills, resource management, effective communication, and coping strategies. Improving coordination and collaboration between health institutions and other related agencies must also be a priority to optimize disaster response. Further research is needed to develop training models and nursing and government policy recommendations to empower nurse leaders during disasters.

Limitations and future study

The study highlights limitations and proposes future research to enhance our understanding of the topic. First, the study was limited to nurses from 4 health centers in West Sulawesi, so the experiences and challenges may differ from those in other areas affected by the earthquake. Therefore, a broader study involving more participants from affected and non-affected earthquake regions is necessary to obtain a more comprehensive picture. Second, the participants in this study are primarily women, so they do not represent the experience of male nurses. Further studies are needed with a balanced proportion of male and female participants. Finally, the data were collected only through FGD, so there was a possibility of not fully exploring the individual experiences of each participant. It is necessary to consider in-depth interview methods to complement the data.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has official approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia (Code: Nu.077/UN2.F12.D121/PPM.00.02/2024). Before participating in the study, the participants were given complete information about the purpose and methodology of the research. The researchers then asked the participants to sign an informed consent form before participating in the study. The confidentiality of the participant’s identity was guaranteed, and the participant was free to withdraw. Their comfort and trust were our top priorities.

Funding

This paper is based on Edi Purnomo’s approved PhD dissertation from the Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia. This research was conducted without the use of any funding.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Edi Purnomo and Achir Yani S. Hamid; Methodology, data analysis, and investigation: Dewi Gayatri and Edi Purnomo; Data collection, and writing: Edi Purnomo and Agus Setiawan; Funding administration: Edi Purnomo; Final approval : All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors were dedicated to transparency and declared no competing interests or conflicts related to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Mamuju Health Polytechnic Indonesia for supporting the primary author throughout the research.

References

- Veenema TG, Griffin A, Gable AR, Macintyre L, Simons RN, Couig MP, et al. Nurses as leaders in disaster preparedness and response-A call to action. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2016; 48(2):187-200. [DOI:10.1111/jnu.12198] [PMID]

- Hopkinson SG, Jennings BM. Nurse leader expertise for pandemic management: Highlighting the essentials. Military Medicine. 2021; 186(12 Suppl 2):9-14. [DOI:10.1093/milmed/usab066] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Labrague LJ, Hammad K. Disaster preparedness among nurses in disaster-prone countries: A systematic review. Australasian Emergency Care. 2024; 27(2):88-96. [DOI:10.1016/j.auec.2023.09.002] [PMID]

- Knebel AR, Toomey L, Libby M. Nursing leadership in disaster preparedness and response. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 2012; 30(1):21-45. [DOI:10.1891/0739-6686.30.21] [PMID]

- Veenema TG, Deruggiero K, Losinski S, Barnett D. Hospital administration and nursing leadership in disasters: An exploratory study using concept mapping. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2017; 41(2):151-63. [DOI:10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000224] [PMID]

- Veenemav T, Losinski SL, Newton SM, Seal S. Exploration and development of standardized nursing leadership competencies during disasters. Health Emergency and Disaster Nursing. 2017; 4(1):26-38. [Link]

- Shuman CJ, Costa DK. Stepping in, stepping up, and stepping out: Competencies for ICU nursing leadership during disasters, emergencies, and outbreaks. American Journal of Critical Care. 2021; 29(5):403-6. [DOI:10.4037/ajcc2020421] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lim HW, Li Z, Fang D. Impact of management, leadership, and group integration on the hospital response readiness for earthquakes. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2020; 48:101586. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101586]

- Adi AW, Shalih O, Shabrina FZ, Rizqi A, Putra AS, Karimah R, et al. [Indonesia disaster risk: Understanding systemic risk in Indonesia (Indonesian)].Indonesia: Pusat Data, Informasi, dan Komunikasi Kebencanaan BNPB; 2023. [Link]

- Ayuningtyas D, Windiarti S, Sapoan Hadi M, Fasrini UU, Barinda S. Disaster preparedness and mitigation in indonesia: A narrative review. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2021; 50(8):1536-46. [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v50i8.6799] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sofyana H, Ibrahim K, Afriandi I, Herawati E. The implementation of disaster preparedness training integration model based on Public Health Nursing (ILATGANA-PHN) to increase community capacity in natural disaster-prone areas. BMC Nursing. 2024; 23(1):105. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-024-01755-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sangkala MS, Gerdtz MF. Disaster preparedness and learning needs among community health nurse coordinators in South Sulawesi Indonesia. Australasian Emergency Care. 2018; 21(1):23-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.auec.2017.11.002] [PMID]

- Winarti W, Gracia N. Exploring nurses’ perceptions of disaster preparedness competencies. Nurse Media Journal of Nursing. 2023; 13(2):236-45. [DOI:10.14710/nmjn.v13i2.51936]

- Ishiwatari M. Disaster risk reduction. In: Lackner M, Sajjadi B, Chen WY, editors. Handbook of climate change mitigation and adaptation. Cham: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-72579-2_147]

- Atwii F, Sandvik KB, Kirch L, Paragi B, Radtke K, Schneider S, et al. World Risk Report 2022. Bochum: Ruhr University Bochum; 2022. [Link]

- Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysical Agency (Badan Meteorologi, Klimatologi, dan Geofisika). [Results of the M 6.2 Mamuju-Majene Earthquake Survey (Indonesian)]. Jakarta: Badan Meteorologi Klimatologi. Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysical Agency (Badan Meteorologi, Klimatologi, dan Geofisika); 2021. [Link]

- Suwargana H, Karim A. [Impact of Earthquake in West Sulawesi and Mitigation Efforts (Indonesian)]. Jurnal Geominerba (Jurnal Geologi, Mineral Dan Batubara). 2022; 7(2):104-18. [Link]

- Purnomo E, Gayatri D, Setiawan A, Hamid AYS. Perception on nurses’ preparedness for flooding disaster: A qualitative study. Jurnal Kesehatan Manarang. 2024; 10(1):11-26. [DOI:10.33490/jkm.v10i1.1267]

- Akbari K, Yari A, Ostadtaghizadeh A. Nurses’ experiences of providing medical services during the Kermanshah earthquake in Iran: A qualitative study. BMC Emergency Medicine. 2024; 24(1):4. [DOI:10.1186/s12873-023-00920-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tas F, Cakir M. Nurses’ knowledge levels and preparedness for disasters: A systematic review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2022; 80:103230. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103230]

- Ahmadi B, Foroushani AR, Tanha N, Abad AM, Asadi H. Study of Functional Vulnerability Status of Tehran Hospitals in Dealing With Natural Disasters. Electron Physician. 2016; 8(11):3198-204. [DOI:10.19082/3198] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Thrwi AM, Mousa A, Hazmi A, Kalfout AM, Kariri HM, Aldabyan TY, et al. Nursing leadership in disaster preparedness and response lessons learned and future directions. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health. 2024; 11(8):3261–5. [DOI:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20241989]

- Guerdan BR. Disaster preparedness and disaster management : The development and piloting of a self-assessment survey to judge the adequacy of community-based physician knowledge. American Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2009; 6(3):32-40. [Link]

- Reed D. Developing nursing leadership skills when working with disaster response programs. Nurs Leader. 2023; 21(3):415-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.mnl.2023.02.001]

- Gallagher CR. Muddling leadership and management in the United States Army. Army Press Online J. 2016; 108:16-32.[Link]

- Demiroz F, Kapucu N. The role of leadership in managing emergencies and disasters. European Journal of Economic & Political Studies. 2012; 5(1):91-101. [Link]

- Lovrić R, Farčić N, Mikšić Š, Včev A. Studying during the covid-19 pandemic: A qualitative inductive content analysis of nursing students’ perceptions and experiences. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(7):188. [DOI:10.3390/educsci10070188]

- Bleiker J, Morgan-Trimmer S, Knapp K, Hopkins S. Navigating the maze: Qualitative research methodologies and their philosophical foundations. Radiography (Lond). 2019; 25(Suppl 1):S4-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.radi.2019.06.008] [PMID]

- Kleinheksel AJ, Rockich-Winston N, Tawfik H, Wyatt TR. Demystifying content analysis. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2020; 84(1):7113. [DOI:10.5688/ajpe7113] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Salehi H, Karampourian A, Gharae H. Explaining the challenges of providing healthcare services during covid-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly. 2024; 9(4):283-94. [DOI:10.32598/hdq.9.4.494.5]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry: Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1985, 416 pp., $25.00 (Cloth). International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1985; 9(4):438-9.[DOI:10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8]

- Lam SKK, Kwong EWY, Hung MSY, Pang SMC, Chiang VCL. Nurses’ preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks: A literature review and narrative synthesis of qualitative evidence. The Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018; 27(7-8):e1244-55. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.14210]

- Madhyvadany M, Panboli S. A review on influence of direction function on employee engagement. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology. 2019; 29(5):1326-31.[Link]

- Maznieda M, Dalila R, Rosnah S, Rohaida I, Rosmanajihah ML, Mizanurfakhri G, et al. The soft skills emergency management that matters at the hardest time: A phenomenology study of healthcare worker’s experiences during Kelantan flood 2014. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2022; 75:102916. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102916]

- Alruwaili RF, Alsadaan N, Alruwaili AN, Alrumayh AG. Unveiling the symbiosis of environmental sustainability and infection control in health care settings: A systematic review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):15728. [DOI:10.3390/su152215728]

- Usher K, Mills J, West C, Casella E, Dorji P, Guo A, et al. Cross-sectional survey of the disaster preparedness of nurses across the Asia-Pacific region. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2015; 17(4):434-43. [DOI:10.1111/nhs.12211] [PMID]

- Labrague LJ, Yboa BC, Mcenroe-Petitte DM, Lobrino LR, Brennan MGB. Disaster Preparedness in Philippine Nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2016; 48(1):98-105. [DOI:10.1111/jnu.12186] [PMID]

- Labrague LJ, Hammad K, Gloe DS, McEnroe-Petitte DM, Fronda DC, Obeidat AA, et al. Disaster preparedness among nurses: A systematic review of literature. International Nursing Review. 2018; 65(1):41-53. [DOI:10.1111/inr.12369] [PMID]

- Farokhzadian J, Mangolian Shahrbabaki P, Farahmandnia H, Taskiran Eskici G, Soltani Goki F. Nurses’ challenges for disaster response: A qualitative study. BMC Emergency Medicine. 2024; 24(1):1-16. [DOI:10.1186/s12873-023-00921-8]

- Druwé P, Monsieurs KG, Gagg J, Nakahara S, Cocchi MN, Élő G, et al. Impact of perceived inappropiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation on emergency clinicians’ intention to leave the job: Results from a cross-sectional survey in 288 centres across 24 countries. Resuscitation. 2021; 158:41-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.10.043] [PMID]

- Djalante R, Lassa J, Setiamarga D, Sudjatma A, Indrawan M, Haryanto B, et al. Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020. Progress in Disaster Science. 2020; 6:100091. [DOI:10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100091] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kheradmand JA, Khankeh H, Borujeni SMH, Nasiri A, Shahrestanki YA, Ghanbari V, et al. Analysis of Healthcare Services in 2019 Arbaeen March: A qualitative study. Health in Emergencies & Disasters Quarterly. 2024; 9(2):125-36. [DOI:10.32598/hdq.9.2.524.1]

- Purnomo E, Hamid AY, Gayatri D, Setiawan A. Challenges and needs in disaster preparedness: A qualitative study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnologia. 2025; 5:1225. [Link]

Protocol: Research |

Subject:

Qualitative

Received: 2024/08/3 | Accepted: 2024/11/5 | Published: 2025/04/1

Received: 2024/08/3 | Accepted: 2024/11/5 | Published: 2025/04/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |