Volume 10, Issue 4 (Summer 2025)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025, 10(4): 315-328 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.AJAUMS.REC.1401.209

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Malekabad E S, Sharififar S, Zareian A, Jafari Golestan N, Azizi M, Pishgooie S A H. Factors Influencing Military Personnel’s Resilience During Natural Disasters in Iran: A Qualitative Study. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2025; 10 (4) :315-328

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-675-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-675-en.html

Ebadallah Shiri Malekabad1

, Simintaj Sharififar1

, Simintaj Sharififar1

, Armin Zareian2

, Armin Zareian2

, Nasrin Jafari Golestan2

, Nasrin Jafari Golestan2

, Maryam Azizi2

, Maryam Azizi2

, Seyed Amir Hosein Pishgooie *3

, Seyed Amir Hosein Pishgooie *3

, Simintaj Sharififar1

, Simintaj Sharififar1

, Armin Zareian2

, Armin Zareian2

, Nasrin Jafari Golestan2

, Nasrin Jafari Golestan2

, Maryam Azizi2

, Maryam Azizi2

, Seyed Amir Hosein Pishgooie *3

, Seyed Amir Hosein Pishgooie *3

1- Department of Health in Emergencies and Disasters and Emergencies, School of Nursing, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- School of Nursing, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- School of Nursing, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,apishgooie@yahoo.com

2- School of Nursing, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- School of Nursing, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 835 kb]

(1151 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3052 Views)

Full-Text: (876 Views)

Introduction

Natural disasters create significant destruction and casualties, resulting in a wide range of incidents with multiple causes and consequences that can be sudden and hazardous [1]. Natural disasters result in various hazardous outcomes, encompassing immediate and long-term risks. Physical hazards include loss of life, injuries, and infrastructure destruction, as seen in events like the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, which caused radioactive contamination and long-term health risks [2, 3]. Psychological hazards comprise posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, for example, post-hurricane Katrina mental health crisis [4], and environmental hazards like soil contamination and habitat loss, deforestation and habitat destruction [5]. Furthermore, disasters can trigger cascading hazards, where one event leads to a chain of subsequent risks, such as an earthquake causing dam failure, flooding, and power disruptions, amplifying the overall impact [6]. In recent years, the frequency of natural disasters has increased globally, driven by factors such as climate change, urbanization, and environmental degradation. The number of natural disasters globally rose from 4212 in 1980–1999 to 7348 in 2000–2019 [7]. Asia is the most disaster-prone region globally, accounting for 40% of all natural disasters in the past two decades. Countries like India, China, and the Philippines have experienced a significant increase in cyclones, floods and landslides [8]. Over the past 20 years, Iran has experienced a significant increase in disasters, primarily due to the emergence of anthropogenic climate change [9]. As one of the first responder groups, military personnel play a critical role in disaster management. However, they face heightened mental health risks due to chronic exposure to high-stress environments [10]. These individuals experience significant stress and heavy workloads while on duty, leading to a higher incidence of mental health disorders that can disrupt their performance and overall well-being [11]. There is increasing concern regarding mental health issues among military personnel [12] who may suffer from various conditions such as musculoskeletal injuries, mood disorders, PTSD, depression, anxiety, mild traumatic brain injuries, psychological injuries and sleep disorders [12-14]. Resilience is a key skill for coping with emergencies, disasters and stressors, defined as the ability to adapt positively despite significant stress [15, 16]. It involves successfully managing challenging events, such as disasters or wars, with minimal or no trauma symptoms and reflects the capacity to thrive in adversity [17]. Resilience includes internal “assets” that refer to inherent personality traits such as coping skills and “resources,” which refer to external protective factors like high-quality social support systems [18]. Given the high rates of mental health issues among military personnel, it is essential to develop strategies to prevent the escalation of psychological symptoms into severe mental health problems [19].

Resilience is critical for ensuring the health and safety of military personnel; it is defined as a system’s capacity to withstand, recover from, improve upon, or adapt to disturbances caused by challenges or stressors [20]. Individuals with higher resilience often return to their baseline state by generating positive emotions after facing stressful challenges without experiencing declines in mental health or the onset of psychological disorders [21]. Resilience reduces mental health risks by minimizing negative emotions, enhancing goal achievement, and improving military personnel’s ability to cope with stress [22-24]. In Iran, where natural disasters cause significant human, financial, and social losses, military personnel are critical as one of the first responder groups first responders [25]. Their stress management and resilience directly influence disaster response outcomes. Enhancing resilience improves mental health and ensures effective performance under pressure, reducing disaster impacts. This study aims to identify factors influencing military personnel’s resilience during natural disasters to advise tailored preventive strategies.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative study was conducted using a content analysis approach. Qualitative content analysis is a suitable method for generating knowledge and new ideas, presenting facts, and providing practical guidance to achieve the goals of this research. The present study was conducted in Tehran, Kermanshah, Lorestan and Golestan provinces, Iran.

Setting and participants

This study selected participants using purposive and accessible sampling methods appropriate for qualitative research. Military personnel were interviewed as individuals who had directly responded to recent emergencies and disasters. Military personnel play a critical role as first responders during disasters and emergencies, helping search for and rescue affected people. While they serve as part of the first responder group, the interviews focused on their experiences and coping mechanisms during relief efforts in emergencies and disasters. This approach allowed us to gain insight into their resilience and individual perspectives, which is critical to understanding how military personnel navigate challenging crises. Key strengths of the military forces include rapid mobilization and deployment, which allows them to quickly assess situations and coordinate relief efforts after natural disasters such as earthquakes and floods. In addition, military medical teams provide emergency health care services, including emergency surgery triage, and often deploy mobile hospitals in areas where civilian health care systems are under strain. The military forces help build community resilience through training and preparedness programs to support long-term recovery. The provinces of Tehran, Kermanshah, Lorestan and Golestan were chosen due to their significant exposure to natural disasters in recent years, including floods and earthquakes (for example, floods in Golestan and Lorestan provinces and an earthquake in Kermanshah). Given the deployment of numerous specialized military units in Tehran, in most disasters and emergencies that the provinces and regions involved cannot respond to promptly, military forces are dispatched to search, rescue, and make relief efforts for their fellow citizens. Tehran as the capital of Iran, and due to the deployment of numerous and diverse specialized military units, in most disasters and emergencies that the provinces and regions involved cannot respond to, forces are dispatched to provide relief and rescue to fellow citizens. Moreover, Tehran, as the capital of Iran, has a diverse population of military personnel (including specialized and unique operations military forces) who have experience providing relief in emergencies and disasters, and their capacity is used in most emergencies and disasters.

By including participants from multiple provinces, we aimed to ensure maximum diversity in the sample and experience participating in recent emergencies and disasters as rescuers. This diversity enriches the data collected and allows for a more comprehensive understanding of resilience factors among military personnel who have directly provided relief in search and rescue and, finally, relief to the affected populations. Participants were selected to ensure maximum diversity in age, gender, marital status, education and more. Data collection took place from July 2022 to April 2023. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: Willingness to participate in the interview and provide necessary information, experience in emergencies and disasters, and at least five years of work experience in military occupations. Individuals unwilling to be interviewed or participate in the study were excluded. The sample size was consistent with qualitative studies and continued until data saturation was reached, meaning sampling continued until no new data emerged, resulting in the selection of 24 military personnel who participated in the interviews.

Collecting data

The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format, scheduled in advance by the principal researcher. They were recorded using a digital voice recorder after obtaining permission from the participants. The recorded interviews were transcribed word-for-word immediately after each session to ensure data saturation and improve the accuracy of the transcripts. Each interview lasted between 30 to 45 minutes and was conducted individually. Additionally, two interviews were held with individuals not part of the participant group to validate the questions and ensure their relevance from the respondents’ perspective. Based on their feedback, necessary adjustments were made to improve any shortcomings. The analysis of the interviews was conducted right after they were completed. The questions focused on open-ended inquiries to identify the factors influencing military resilience. Participants were asked questions such as: “Please describe your experiences from missions and your presence in emergencies and disasters as a military individual?” “How did you cope with these situations?” “What characteristics do you think helped you deal with these situations?” “Besides your traits and abilities, what else has helped you cope with specific situations?”

Data analysis

The content analysis method was used to analyze the data at each stage. Qualitative content analysis is a specialized method for processing scientific data to determine the presence of specific words and concepts in the text, allowing for data summarization, description, and interpretation [26]. The data analysis method followed the framework of Kyngäs et al. which included open coding, listing codes, grouping, categorizing and abstracting [27]. Open coding is the initial step in the coding process of qualitative data analysis. It involves breaking down qualitative data into discrete parts, examining them closely and comparing them for similarities and differences. During open coding, researchers identify and label concepts, themes, or categories that emerge from the data [28]. Abstraction in qualitative research refers to synthesizing and summarizing the coded data into broader themes or categories. It involves moving from specific observations to more generalized concepts that capture the essence of the data [29]. During the preparation phase, the transcribed text from each interview was read multiple times to facilitate immersion in the data. Each interview was then divided into semantic units, summarized and coded. In the organization phase, the researchers created an unconstrained matrix to analyze the data based on a general conceptual model of resilience derived from McLarnon et al’s. study [30]. After each interview, the transcribed text was read and reviewed multiple times to ensure immersion in the data. The recorded audio was listened to repeatedly, and handwritten notes were reviewed several times to decide how to divide the text into semantic units. The abstraction of semantic units and code selection were carried out. The principal researcher analyzed the interview texts independently, while other authors oversaw the data analysis process. MAXQDA software, version 10 was used to help organize, classify, and retrieve data.

Reliability of the study

Trustworthiness was assessed as an alternative to validity and reliability using the gold standard outlined by Guba and Lincoln [31]. To ensure trustworthiness and rigor in the data, credibility was established through continuous study and review of the data (transcribing interviews onto paper and reviewing them until the main themes emerged), peer review of the analysis by the authors, and member checking of the written content by the participants. For conformability, a detailed description of the findings was provided. To ensure transferability, consultations were held with two experts who were not involved in the research. The researcher shared parts of the interviews and interpretations with them to discuss meanings and reach a consensus on ideas. Methods for determining credibility included member checking, reviewing interview texts, revising initial codes and categories, and obtaining feedback on the data.

Results

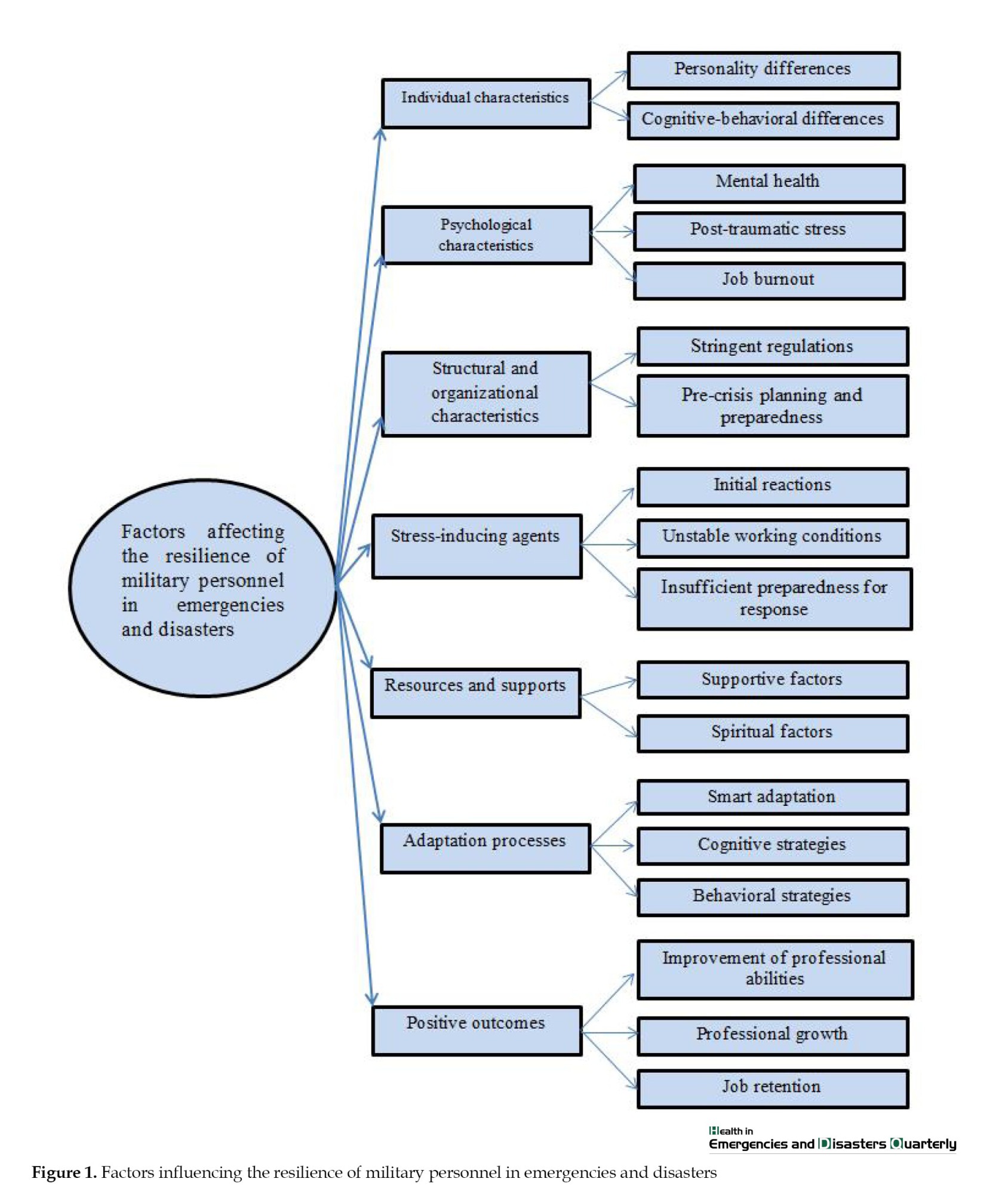

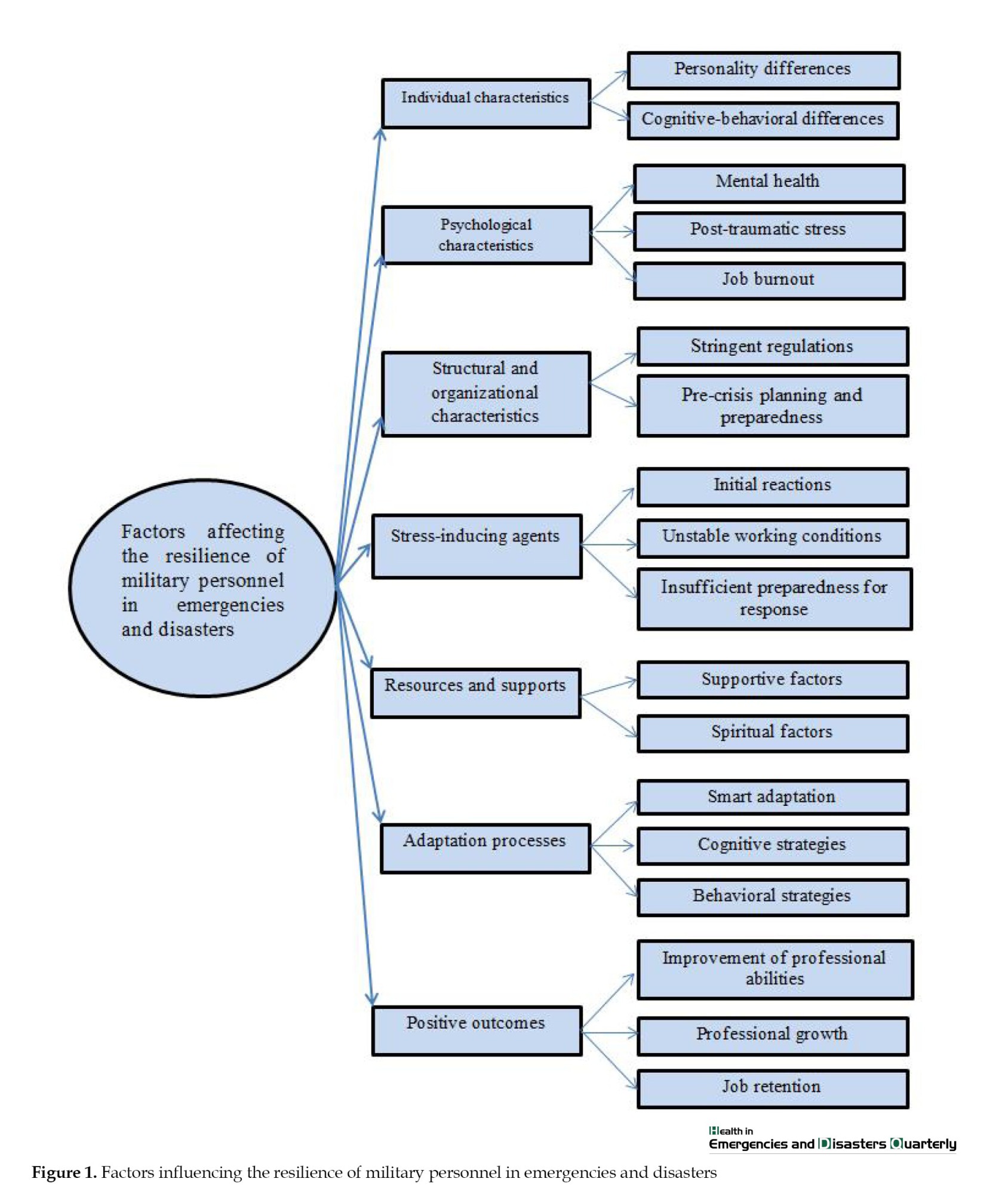

The study sample involved 24 military personnel. The roles of the participants are specified: 15 served as rescuers, 5 were unit leaders, and 4 acted as rescue operation commanders. The educational qualifications of the participants were a bachelor’s degree in 16 participants, a master’s degree in 4 and a doctoral degree in 4. This information is relevant because it can affect their understanding of resilience and their ability to articulate their experiences during interviews. The average age of the participants was 39.29 years. Their average work experience is 18.3 years, with an average of 2 experiences in emergencies. These qualifications suggest the participants have substantial professional experience, likely notifying their views on resilience in high-pressure situations. The paragraph concludes with findings from the content analysis of semi-structured interviews, indicating that eighteen factors influence military resilience in emergencies. These factors were organized into seven main categories (Figure 1). This summary implies that the study aims to identify and categorize key elements contributing to resilience, which can be critical for developing training or support systems for military personnel.

Individual characteristics

This category is derived from discussions about personal characteristics and coping mechanisms influencing resilience. Individual factors encompass personal characteristics and coping strategies that affect resilience. These factors were identified through thematic analysis of participant interviews, highlighting how unique personal experiences and traits contribute to resilience in stressful situations. One participant said: “I always try to focus on what I can control. My previous disaster experiences taught me to stay calm and think clearly.”

Personality differences

Military personnel mentioned characteristics such as patience, compassion, sacrifice, selflessness, responsibility, empathy, and altruism. One participant shared, “During the earthquake and the call for the mission, despite severe family problems, I went on the mission and stayed there for several days to help” (Participant [P] 4).

Cognitive-behavioral differences

Military personnel referred to characteristics such as interest in teamwork, commitment to work, responsibility, ability to cope with challenges, work ethic, decision-making power, appreciation, dutifulness, ability to manage situations during crises and high presence of mind, which fall under the category of individual cognitive-behavioral abilities. They also mentioned characteristics such as having high physical readiness, robustness, sufficient skills, high speed of action, work experience, management ability and communication skills, which refer to the cognitive flexibility of military personnel. These qualities create a sense of meaning and coherence, and their content includes active learning, being in search of new experiences, actively testing and having an open and highly accurate mind. “I learned to control my emotions and feelings in emergencies and disasters, control myself at that time, and help. I learned and applied this in my own life, too. When something comes up, I gather myself and try to use my abilities to solve that problem or do whatever I can” (P8).

Psychological characteristics

Employment in special occupations such as military occupations and in special situations such as presence at the scene of emergencies and disasters is one of the stressful experiences that threatens the mental health of individuals, which is followed by PTSD and job burnout for personnel. This category is named based on insights related to mental health, emotional regulation, and stress management strategies. Psychological factors refer to mental health aspects, including stress management and emotional regulation. Participants indicated that their ability to manage anxiety and maintain a positive mindset significantly affected their resilience. One participant said: “Maintaining a positive outlook was crucial for me. I learned that if I could keep my mind clear, I could handle anything that came my way.”

Mental health

I always feel stress and anxiety when starting a mission that whether my family and I are safe or not (P15).

Posttraumatic stress

After the earthquake, I had nightmares for several consecutive nights and woke up feeling like the rubble had fallen on my head (P3).

Job burnout

I feel that after 20 years of service, I no longer have the initial motivation and energy and get tired earlier than before, and my tolerance has decreased (P10) .

Structural and organizational characteristics

Structural and organizational characteristics play a significant role in the resilience of military personnel. This category includes stringent regulations, pre-emergency, disaster planning, and preparedness. This category reflects the influence of military structure, leadership, and organizational support on resilience. This subgroup includes elements related to the military structure and organizational support systems that facilitate resilience. Insights from interviews revealed that effective communication and leadership play vital roles in preparing personnel for natural disasters. One participant said: “Our unit had a solid plan, and knowing that gave us confidence. Good leadership made us feel supported during the crisis.”

Stringent regulations

In the content analysis conducted, military personnel referred to strict organizational regulations, such as the chain of command and its application to all matters, low or undefined mission allowances, failure to timely replace effective and fresh forces, recruitment and training of skilled and experienced personnel, attracting active personnel interested in providing services in emergencies and disasters, and ensuring the safety of personnel during missions. One participant stated: “Everything in this organization is dictated; no specific laws exist. It means whatever the commander says is what it is. I have been in all crises without receiving a single Rial of mission allowance” (P22).

Pre-emergencies, disasters planning and preparedness

The preparedness of military personnel before emergencies and disasters include developing and implementing necessary training, dispatching specialized and trained personnel related to emergencies and disasters, ensuring food and welfare facilities and providing up-to-date equipment. Personnel indicated, “It seems that the organization just needs to send us to be present; it doesn’t matter what our specialty is or whether we have received training” (P17).

Stress-inducing agents

Throughout their lives, military personnel encounter various stressful events and factors. Employment in military jobs, especially under specific conditions such as being present at the scene of emergencies and disasters, is one of the stressful experiences individuals face. Many factors exacerbate the effects of these stress-inducing agents. This category captures external pressures that challenge resilience, as articulated by participants. Stress-inducing agents are external pressures that can negatively impact resilience. Participants discussed how unpredictable situations, such as sudden evacuations or lack of resources, heightened stress levels and challenged their coping abilities. One participant said: “The uncertainty was the hardest part. When we didn’t know what was happening next, it created a lot of anxiety among us.”

Initial reactions

The resilience process is triggered by an individual’s initial response to an incident or emergency. In emergencies and disasters, victims and those around them generally do not maintain an appropriate mental-emotional balance; they tend to be demanding and highly irritable. In such situations, military personnel face traumatic and distressing injuries and experience indirect trauma. One participant noted: “For a long time, I couldn’t laugh from the bottom of my heart; the image of the half-destroyed bodies we pulled out from under the rubble kept coming to my mind” (P15).

Unstable working conditions

Characteristics of being in emergencies and disasters include unpredictable situations and poor inter-organizational management and coordination. Working under unstable weather conditions, such as floods or earthquakes, complicates rescue efforts. One participant noted: “Everyone was playing their tune, and there was no unified command; for example, the flood barriers we built yesterday were destroyed by another organization with a bulldozer the next day” (P24).

Insufficient preparedness for response

In responding to incidents during emergencies and disasters, having adequate and appropriate infrastructure, space, facilities, and equipment is essential. One participant stated: “In the earthquake and those poor sanitary conditions, having access to trailers and pre-fabricated bathrooms and toilets became the people’s wish” (P7).

Resources and support

Interpersonal relationships with expressions of positive emotions, affirmation and validation of the individual’s beliefs, and seeking help from others help the individual. In this category, two items were identified: Support and spirituality. The content of this category includes having access to and receiving support through relationships with family, friends and significant people in life, the community and colleagues in the workplace. This category represents material resources and emotional support systems identified as crucial for coping. Resources and support include tangible resources (like equipment) and emotional support from peers and family. The data indicated that access to resources significantly mitigated stress and enhanced resilience. One participant said: “Having the right gear made a huge difference. Knowing my family was safe helped me focus on my duties without worrying.”

Supportive factors

In the content analysis, military personnel referred to the supportive role of family members, friends and colleagues in reducing stress. The nature of work during emergencies and disasters is such that services are provided in a group setting, especially during rescue operations and when dealing with many injured people. For this reason, collective support strengthens the group, facilitates service delivery and reduces stress. One participant noted: “In those special circumstances, I couldn’t do much work and was confused, but then I talked to my brother, and he helped and calmed me down” (P19).

Family support

Emotional ties among family members are strengthened through shared recreation and leisure time, fostering a sense of connection. Effective communication involves the exchange of thoughts, opinions and information, which is essential for problem-solving and managing relationships. Support encompasses the perception that comfort is available from others and can be provided to them, including emotional, tangible, instrumental, informational and spiritual support. Closeness is characterized by love, intimacy and attachment, while nurturing reflects the parenting skills contributing to healthy development. Additionally, adaptability refers to the ease with which individuals adjust to changes associated with military life, including flexible roles within the family. These factors are crucial in enhancing resilience among personnel and their families.

Social support

This support includes emotional, informational and practical assistance from family, friends, and community members. Social support can help individuals cope with stress and adversity by providing a sense of belonging, validation, and encouragement. Access to community resources, such as mental health services, educational programs and recreational activities, can enhance resilience. Communities that provide support systems, such as counseling services, peer support groups, and skill-building workshops, empower individuals to develop resilience and cope more effectively.

Organizational support

The most important forms of organizational support that organizations should ensure for military personnel including organizational rewards, favorable job conditions, assistance to military personnel in performing tasks efficiently and managing stressful situations, and support from their commanders.

Colleagues support

Emotional support from colleagues is essential for military personnel who face the unique stresses of their roles. This type of support encompasses empathy, understanding and encouragement during challenging times. Informational support, which involves sharing knowledge, advice and resources, is also vital in military settings. This support can include guidance on coping strategies, operational procedures and mental health resources. Colleagues often provide valuable insights based on their experiences, enabling others to navigate difficult situations more effectively. Studies have shown that access to informational support correlates with better mental health outcomes and increased resilience among military personnel. Practical support is another critical component, encompassing tangible assistance such as help with tasks, sharing workloads, or providing logistical aid. In the military, where teamwork is paramount, practical support can significantly alleviate stress and enhance operational effectiveness. For instance, when team members assist each other with duties or share resources, it fosters a collaborative environment that strengthens resilience. Building a supportive culture within military units is essential for maximizing the benefits of colleagues’ support.

Spiritual factors

Military personnel believe that trusting in God and entrusting themselves to Him makes it easier to endure emergencies, disasters, and difficult situations. “During the mission, I do the tasks for the sake of God and always trust in God (P21).

Sense of purpose and meaning

Spirituality often gives individuals a profound sense of purpose and meaning. A clear sense of purpose can motivate personnel working in high-stress environments, such as military or healthcare settings. It helps them understand the significance of their roles and responsibilities, which can foster commitment and dedication. This sense of purpose can act as a protective factor, enabling individuals to navigate challenges and maintain their morale even in difficult circumstances.

Coping mechanism

Spiritual practices, such as prayer, meditation, and reflection, can serve as effective coping mechanisms for personnel dealing with stress and trauma. These practices can help individuals manage their emotional responses, reduce anxiety and promote relaxation. Research has shown that spirituality can enhance emotional regulation and provide comfort during times of distress, leading to improved mental health outcomes. These coping strategies can be particularly beneficial in high-pressure situations where personnel may experience overwhelming emotions.

Social support and community

Spirituality often fosters a sense of community and belonging, which is crucial for resilience. This sense of community can alleviate isolation and loneliness, which are common in high-stress professions. Support from peers who share similar spiritual beliefs can enhance coping strategies and provide a safe space for discussing experiences and emotions related to their work.

Moral and ethical framework

Spirituality can offer personnel a moral and ethical framework that guides their actions and decisions, particularly in high-stress situations. This framework can help individuals navigate the complexities of their roles and the moral dilemmas they may face, reinforcing their sense of integrity and accountability. A clear set of values rooted in spirituality can bolster resilience by giving personnel the confidence to make difficult decisions and maintain their sense of self in challenging environments. This moral grounding can also contribute to posttraumatic growth, allowing individuals to find meaning in their experiences and emerge stronger.

Adaptation processes

These processes are related to the individual’s recovery from an incident or unpleasant experience, using individual capacities and external support and achieving positive outcomes in work and life if successful. The content analysis divided the results into three subcategories, which are discussed separately below. This category is named for individuals’ strategies to adjust to challenges, emphasizing flexibility and learning. Adaptation processes refer to individuals’ strategies to adapt to challenging situations. Participants stressed the importance of flexibility and learning from experiences as key components of their resilience. Participant Quote: “Every disaster teaches you something new. Adapting quickly became second nature after a few experiences.”

Smart adaptation

Military personnel referred to characteristics such as self-awareness, self-esteem, a sense of being helpful, and a sense of humor. “Just the fact that a helpless and suffering person thanks you and prays for you and your family is the highest reward possible (P23).

Cognitive strategies

Beliefs and convictions enable individuals to regain a sense of meaning after each failure or loss. Having a mindset focused on living in the present moment, understanding the reality of the situation over time, maintaining a realistic view of the nature of work in emergencies and disasters, engaging in self-reflection and self-criticism, separating work and life issues, analyzing problems to find the best solutions, and recognizing positive aspects to cope with difficult work situations were included in this subcategory. One participant stated: “I cope with it. For everyone, these events can happen. I practiced calming down, telling myself that this is also part of life and that nothing can be done about it, and I have to get along with it” (P13).

Behavioral strategies

This subcategory includes mechanisms related to understanding and controlling negative and ineffective behaviors. Codes such as exercise and physical activity, meditation skills, spending time with family and loved ones, reading, communicating with others about upsetting matters, listening to motivational speeches, music, and prayer and supplication were included in this subcategory. One participant stated: “I talk to my friends, unload myself a bit; they express sympathy with me, and I feel calm” (P2).

Positive outcomes in work and life

Positive life outcomes can include adaptation, improvement, and opening up new paths in life when facing difficulties. This category highlights the beneficial effects of resilience on personal life and professional duties. This subgroup highlights resilience’s beneficial effects on professional duties and personal life. Participants noted that overcoming challenges during disasters often led to increased confidence and improved relationships. One participant said: “Going through tough times together strengthened our bond as a team. I also found that I appreciated my family more after those experiences.”

Improvement of professional abilities

Facing challenging situations, various conditions of emergencies and disasters, and close, intimate relationships with other organizations involved in service delivery increases knowledge and skills. One participant stated: “Scientifically and skillfully, I got much better. I learned a lot and became more capable” (P23).

Professional growth

Presence and relief in emergency and disaster situations and the need to communicate with affected individuals and manage these relationships have enhanced skills such as communication and self-expression. Their self-confidence has also grown as their knowledge and skills have increased. One participant stated: “I became much more logical; as a result of being present and providing relief in emergencies and disasters, my social relationships have greatly improved” (P1).

Job retention

Staying in the military profession and being present in emergencies and disasters, when properly guided and led by the organization and driven by personal interest and desire rather than compulsion, can be considered a positive outcome of resilience. One participant stated: “Being a military person and doing military work is a dynamic, people-oriented, living, and orderly profession. Well, I love it; I am in love with my job and uniform” (P11).

Discussion

The conceptual map developed in this study visually represents the interconnections among the various factors influencing the resilience of military personnel during natural disasters. The factors influencing the resilience of military personnel in emergencies and disasters are categorized into seven key categories: Individual characteristics, psychological characteristics, structural and organizational characteristics, stress-inducing, resources and supports, adaptation processes, and positive outcomes. Each category encompasses several specific factors that contribute to overall resilience. Those who possess resilience can plan to achieve their goals, maintain a positive outlook on themselves, trust in their abilities, and possess skills in communication, assertiveness, readiness to listen to others, and respect for the feelings and beliefs of others. They have order, stability, and security in their personal lives, feel empowered to face challenges, and approach problems in a problem-solving manner [32]. The present study’s findings indicate that having specific individual characteristics in various cognitive and behavioral categories—combining knowledge, skills, and experience is one of the most important factors. Individual characteristics (such as personal traits, having a higher purpose, autonomy, etc.) can significantly impact the improvement of resilience [33]. Research shows that structured team-building exercises can promote patience, compassion and altruism by fostering social cohesion and mutual support among individuals in disaster situations. Clear communication and shared goals help cultivate responsibility and the ability to cope with challenges, empowering personnel to take ownership of their roles. Creating an environment of trust and mutual respect enhances commitment and presence of mind, while mindfulness training improves emotional regulation and stress management. Additionally, conducting regular after-action reviews encourages continuous learning and adaptation based on past experiences. By integrating these strategies, military organizations can significantly strengthen the resilience of their personnel in high-pressure situations [34, 35].

Psychological characteristics, which include mental health, posttraumatic stress, and job burnout, constituted the second component. Entering the military sphere due to the stresses of military life and facing potential educational and occupational challenges leads to significant changes in individuals’ personal and social lifestyles. These changes may manifest, depending on the prior context, as increased sensitivity to external stimuli, turmoil, stress, anxiety and mood fluctuations leaving detrimental effects on the mental health of military personnel. Such psychological damage may lead to suicidal thoughts and self-harm [36]. Therefore, by implementing necessary measures to enhance resilience, many psychological variables, including job burnout, posttraumatic stress, and mental health, can be moderated [37]. Findings from Lakioti et al. [38] indicate that resilience in therapists has a significant relationship with psychological factors, including mental health, posttraumatic stress, and job burnout and these concepts are useful variables in the context of resilience. In the study by Houpy et al. [39], individuals without symptoms of job burnout exhibited higher resilience, highlighting the role of job burnout as a psychological characteristic in individuals’ resilience. Organizations can implement various targeted strategies to strengthen the psychological resilience of military personnel during natural disasters. First, they should focus on mental skills training emphasizing cognitive resilience through stress management and emotional regulation. Team-based exercises can foster teamwork and connectedness, strengthening social support networks. Establishing peer support programs can facilitate open communication and emotional sharing, helping to reduce feelings of isolation [40]. Structural and organizational characteristics are considered the third component. In emergencies and disasters, organizational resilience is the ability to return to the original state and develop capabilities while creating new opportunities. As resilient entities, military organizations possess an increasing capacity for managing emergencies and disasters and enable innovative solutions to adapt to and cope with unforeseen conditions [41]. However, timely provision of financial resources, appropriate equipment, and a shortage of qualified personnel are significant internal barriers to organizational enhancement. Therefore, by strengthening social infrastructures at the community level, utilizing emergency and disaster management technologies and attracting committed and innovative human resources, organizations can better fortify their foundations for resilience [36, 42]. The results of Alavi’s study showed that participants experienced both short-term and long-term mental health effects in responding to disasters. They identified important ways that structural and systemic factors influenced their mental health, including their experiences with disaster response preparedness, post-disaster debriefing, peer support, recognition from organizations and the public for healthcare providers’ contributions and psychological support in the workplace [43]. The present study’s findings indicate that stress-inducing agents are the fourth component. Military personnel encounter various stressful events and factors throughout their lives. Yousefi et al. [37] showed that maladaptive mechanisms such as aggression among military personnel had a lower average compared to the civilian group, and the level of psychological resilience was higher in military individuals. To improve resilience among military personnel facing unstable working conditions and inadequate disaster response preparedness, organizations should establish clear communication protocols, conduct regular training exercises, and cultivate a supportive work culture that prioritizes mental health resources. Furthermore, adopting flexible operational structures and performing after-action reviews can promote continuous learning and adaptability, enabling teams to manage better the challenges presented by disaster situations [44, 45]. The fifth category was resources and supports, which included supportive and spiritual factors. Support encompasses various aspects such as family, community, friends, colleagues, media and team members. This factor is a fundamental category of resilience that positively correlates with the psychological state of military personnel [46]. Good social support [47], support from friends during missions [48], and support from team leaders are among the most important components of resilience in crises [49]. Sharing responsibilities and tasks with colleagues reduces the burden of challenging situations [50]. Spirituality and religion can help individuals cope with stress in emergencies and disasters. Therefore, relying on God and focusing on spirituality are effective strategies for managing stress and enhancing resilience in emergencies and disasters [51]. Findings from Dourania indicated that social support can predict vulnerability to stress, and changes in this factor can effectively reduce individuals’ vulnerability when facing stress [52]. Additionally, fostering a culture of social support through peer networks and mentorship can provide essential external resources that individuals can rely on during recovery from adverse experiences [53]. It is suggested that military personnel during disasters, organizations should focus on improving support resources. This action includes strengthening family support through programs like focus, fostering social support networks via community events and peer groups, and ensuring robust organizational support with access to counseling services and tailored programs. Additionally, promoting colleague support through team-building activities and mentorship can create a culture of mutual assistance. By implementing these strategies, military organizations can significantly bolster the resilience of their personnel and their families [54].

Adaptation processes are among the most significant positive outcomes of resilience and a protective category. Some believe three or more protective factors are needed to become resilient and the chances of adverse outcomes are high in individuals who face adversity and have few protective factors [55]. When confronted with adversity, a resilient person reaches a baseline level of functioning and sometimes even higher, leading to their successful adaptation in life. For this reason, Timalsina and Songwathana consider adaptation an outcome of resilience [56]. Additionally, individuals with positive emotions, hope, humor, and self-esteem report higher levels of resilience [57, 58]. It is suggested that military personnel can implement several strategies during disasters. First, resilience training programs can be introduced, focusing on skill development in areas such as emotional regulation, problem-solving, and effective communication, which have been shown to enhance coping mechanisms in stressful situations [59]. The seventh category pertains to the positive transformations of resilience, which includes three items: Improvement of professional abilities, professional growth and retention. Bjerknes concluded that professional competence plays a significant role in professional resilience [60]. Studies have shown that employee resilience positively correlates with job performance [61] and organizational commitment [62]. Over time, and in certain situations, such as witnessing bodies at emergency scenes and emergencies and disasters, providing services in unpleasant situations, and other reasons, individuals may experience fatigue and become reluctant to continue collaborating in those conditions [63, 64]. Positive outcomes in work and life for military personnel are significantly influenced by resilience, which protects against stress and adverse psychological effects. Research indicates that higher resilience is associated with improved mental health, reduced job stress and better adaptation to challenging circumstances, leading to increased job satisfaction and overall well-being [65].

Identifying key factors influencing resilience allows for a more strategic allocation of resources to support military personnel during a crisis. Understanding the resilience factors can enhance crisis preparedness planning by integrating strategies that bolster personnel resilience into emergency response protocols. By implementing these programs, military organizations can also improve their ability to effectively support personnel during emergencies and disasters while fostering a culture of resilience that benefits individuals and operational effectiveness.

Conclusion

The findings of this qualitative study indicate that military personnel can achieve positive resilience outcomes through adaptive processes in cognitive and behavioral categories during emergencies and disasters. In these processes, they must possess specific individual characteristics and professional abilities, combining knowledge, skills and experience. Military personnel are often more vulnerable to psychological stress for various reasons. Therefore, they must have access to social support from family, organizations, friends and colleagues. Additionally, the effective implementation of structural and organizational factors significantly impacts the resilience of personnel. Future research could explore the long-term effects of resilience factors on military personnel’s mental health and job performance over time, particularly after experiencing multiple disasters. Research could focus on evaluating specific interventions designed to enhance resilience among military personnel, assessing their effectiveness in various contexts, and identifying which strategies yield the best outcomes.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size of 24 participants may limit the generalizability of the findings. To address this, we used purposive sampling to ensure diversity and recommend future studies include larger, more representative samples. Second, the qualitative nature of the research relies on subjective experiences, which may introduce bias. We mitigated this through triangulation and involving multiple researchers in data analysis. Third, focusing on specific provinces may overlook regional differences. We selected diverse regions to capture varied experiences and suggest expanding the scope in future research. Fourth, self-reported data may lead to response bias. We ensured anonymity and used open-ended questions to encourage honest responses. Finally, the study did not explore long-term effects or external factors like family support. We recommend longitudinal studies and further research on external resilience factors to address these gaps.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.AJAUMS.REC.1401.209). After explaining the study’s objectives to the participants, they were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. The participants completed a written informed consent form. To maintain confidentiality and privacy, the names of the participants were changed to codes, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their names and other information.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Ebadallah Shiri Malekabad and Seyed Amir Hosein Pishgooie; Methodology: Ebadallah Shiri Malekabad, Armin Zareian, Nasrin Jafari Golestan, and Maryam Azizi; Investigation: Ebadallah Shiri Malekabad, Seyed Amir Hosein Pishgooie, and Simintaj Sharififar; Writing the original draft: Seyed Amir Hosein Pishgooie; Review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the authors of the included studies who graciously provided additional data.

References

Natural disasters create significant destruction and casualties, resulting in a wide range of incidents with multiple causes and consequences that can be sudden and hazardous [1]. Natural disasters result in various hazardous outcomes, encompassing immediate and long-term risks. Physical hazards include loss of life, injuries, and infrastructure destruction, as seen in events like the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, which caused radioactive contamination and long-term health risks [2, 3]. Psychological hazards comprise posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, for example, post-hurricane Katrina mental health crisis [4], and environmental hazards like soil contamination and habitat loss, deforestation and habitat destruction [5]. Furthermore, disasters can trigger cascading hazards, where one event leads to a chain of subsequent risks, such as an earthquake causing dam failure, flooding, and power disruptions, amplifying the overall impact [6]. In recent years, the frequency of natural disasters has increased globally, driven by factors such as climate change, urbanization, and environmental degradation. The number of natural disasters globally rose from 4212 in 1980–1999 to 7348 in 2000–2019 [7]. Asia is the most disaster-prone region globally, accounting for 40% of all natural disasters in the past two decades. Countries like India, China, and the Philippines have experienced a significant increase in cyclones, floods and landslides [8]. Over the past 20 years, Iran has experienced a significant increase in disasters, primarily due to the emergence of anthropogenic climate change [9]. As one of the first responder groups, military personnel play a critical role in disaster management. However, they face heightened mental health risks due to chronic exposure to high-stress environments [10]. These individuals experience significant stress and heavy workloads while on duty, leading to a higher incidence of mental health disorders that can disrupt their performance and overall well-being [11]. There is increasing concern regarding mental health issues among military personnel [12] who may suffer from various conditions such as musculoskeletal injuries, mood disorders, PTSD, depression, anxiety, mild traumatic brain injuries, psychological injuries and sleep disorders [12-14]. Resilience is a key skill for coping with emergencies, disasters and stressors, defined as the ability to adapt positively despite significant stress [15, 16]. It involves successfully managing challenging events, such as disasters or wars, with minimal or no trauma symptoms and reflects the capacity to thrive in adversity [17]. Resilience includes internal “assets” that refer to inherent personality traits such as coping skills and “resources,” which refer to external protective factors like high-quality social support systems [18]. Given the high rates of mental health issues among military personnel, it is essential to develop strategies to prevent the escalation of psychological symptoms into severe mental health problems [19].

Resilience is critical for ensuring the health and safety of military personnel; it is defined as a system’s capacity to withstand, recover from, improve upon, or adapt to disturbances caused by challenges or stressors [20]. Individuals with higher resilience often return to their baseline state by generating positive emotions after facing stressful challenges without experiencing declines in mental health or the onset of psychological disorders [21]. Resilience reduces mental health risks by minimizing negative emotions, enhancing goal achievement, and improving military personnel’s ability to cope with stress [22-24]. In Iran, where natural disasters cause significant human, financial, and social losses, military personnel are critical as one of the first responder groups first responders [25]. Their stress management and resilience directly influence disaster response outcomes. Enhancing resilience improves mental health and ensures effective performance under pressure, reducing disaster impacts. This study aims to identify factors influencing military personnel’s resilience during natural disasters to advise tailored preventive strategies.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative study was conducted using a content analysis approach. Qualitative content analysis is a suitable method for generating knowledge and new ideas, presenting facts, and providing practical guidance to achieve the goals of this research. The present study was conducted in Tehran, Kermanshah, Lorestan and Golestan provinces, Iran.

Setting and participants

This study selected participants using purposive and accessible sampling methods appropriate for qualitative research. Military personnel were interviewed as individuals who had directly responded to recent emergencies and disasters. Military personnel play a critical role as first responders during disasters and emergencies, helping search for and rescue affected people. While they serve as part of the first responder group, the interviews focused on their experiences and coping mechanisms during relief efforts in emergencies and disasters. This approach allowed us to gain insight into their resilience and individual perspectives, which is critical to understanding how military personnel navigate challenging crises. Key strengths of the military forces include rapid mobilization and deployment, which allows them to quickly assess situations and coordinate relief efforts after natural disasters such as earthquakes and floods. In addition, military medical teams provide emergency health care services, including emergency surgery triage, and often deploy mobile hospitals in areas where civilian health care systems are under strain. The military forces help build community resilience through training and preparedness programs to support long-term recovery. The provinces of Tehran, Kermanshah, Lorestan and Golestan were chosen due to their significant exposure to natural disasters in recent years, including floods and earthquakes (for example, floods in Golestan and Lorestan provinces and an earthquake in Kermanshah). Given the deployment of numerous specialized military units in Tehran, in most disasters and emergencies that the provinces and regions involved cannot respond to promptly, military forces are dispatched to search, rescue, and make relief efforts for their fellow citizens. Tehran as the capital of Iran, and due to the deployment of numerous and diverse specialized military units, in most disasters and emergencies that the provinces and regions involved cannot respond to, forces are dispatched to provide relief and rescue to fellow citizens. Moreover, Tehran, as the capital of Iran, has a diverse population of military personnel (including specialized and unique operations military forces) who have experience providing relief in emergencies and disasters, and their capacity is used in most emergencies and disasters.

By including participants from multiple provinces, we aimed to ensure maximum diversity in the sample and experience participating in recent emergencies and disasters as rescuers. This diversity enriches the data collected and allows for a more comprehensive understanding of resilience factors among military personnel who have directly provided relief in search and rescue and, finally, relief to the affected populations. Participants were selected to ensure maximum diversity in age, gender, marital status, education and more. Data collection took place from July 2022 to April 2023. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: Willingness to participate in the interview and provide necessary information, experience in emergencies and disasters, and at least five years of work experience in military occupations. Individuals unwilling to be interviewed or participate in the study were excluded. The sample size was consistent with qualitative studies and continued until data saturation was reached, meaning sampling continued until no new data emerged, resulting in the selection of 24 military personnel who participated in the interviews.

Collecting data

The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format, scheduled in advance by the principal researcher. They were recorded using a digital voice recorder after obtaining permission from the participants. The recorded interviews were transcribed word-for-word immediately after each session to ensure data saturation and improve the accuracy of the transcripts. Each interview lasted between 30 to 45 minutes and was conducted individually. Additionally, two interviews were held with individuals not part of the participant group to validate the questions and ensure their relevance from the respondents’ perspective. Based on their feedback, necessary adjustments were made to improve any shortcomings. The analysis of the interviews was conducted right after they were completed. The questions focused on open-ended inquiries to identify the factors influencing military resilience. Participants were asked questions such as: “Please describe your experiences from missions and your presence in emergencies and disasters as a military individual?” “How did you cope with these situations?” “What characteristics do you think helped you deal with these situations?” “Besides your traits and abilities, what else has helped you cope with specific situations?”

Data analysis

The content analysis method was used to analyze the data at each stage. Qualitative content analysis is a specialized method for processing scientific data to determine the presence of specific words and concepts in the text, allowing for data summarization, description, and interpretation [26]. The data analysis method followed the framework of Kyngäs et al. which included open coding, listing codes, grouping, categorizing and abstracting [27]. Open coding is the initial step in the coding process of qualitative data analysis. It involves breaking down qualitative data into discrete parts, examining them closely and comparing them for similarities and differences. During open coding, researchers identify and label concepts, themes, or categories that emerge from the data [28]. Abstraction in qualitative research refers to synthesizing and summarizing the coded data into broader themes or categories. It involves moving from specific observations to more generalized concepts that capture the essence of the data [29]. During the preparation phase, the transcribed text from each interview was read multiple times to facilitate immersion in the data. Each interview was then divided into semantic units, summarized and coded. In the organization phase, the researchers created an unconstrained matrix to analyze the data based on a general conceptual model of resilience derived from McLarnon et al’s. study [30]. After each interview, the transcribed text was read and reviewed multiple times to ensure immersion in the data. The recorded audio was listened to repeatedly, and handwritten notes were reviewed several times to decide how to divide the text into semantic units. The abstraction of semantic units and code selection were carried out. The principal researcher analyzed the interview texts independently, while other authors oversaw the data analysis process. MAXQDA software, version 10 was used to help organize, classify, and retrieve data.

Reliability of the study

Trustworthiness was assessed as an alternative to validity and reliability using the gold standard outlined by Guba and Lincoln [31]. To ensure trustworthiness and rigor in the data, credibility was established through continuous study and review of the data (transcribing interviews onto paper and reviewing them until the main themes emerged), peer review of the analysis by the authors, and member checking of the written content by the participants. For conformability, a detailed description of the findings was provided. To ensure transferability, consultations were held with two experts who were not involved in the research. The researcher shared parts of the interviews and interpretations with them to discuss meanings and reach a consensus on ideas. Methods for determining credibility included member checking, reviewing interview texts, revising initial codes and categories, and obtaining feedback on the data.

Results

The study sample involved 24 military personnel. The roles of the participants are specified: 15 served as rescuers, 5 were unit leaders, and 4 acted as rescue operation commanders. The educational qualifications of the participants were a bachelor’s degree in 16 participants, a master’s degree in 4 and a doctoral degree in 4. This information is relevant because it can affect their understanding of resilience and their ability to articulate their experiences during interviews. The average age of the participants was 39.29 years. Their average work experience is 18.3 years, with an average of 2 experiences in emergencies. These qualifications suggest the participants have substantial professional experience, likely notifying their views on resilience in high-pressure situations. The paragraph concludes with findings from the content analysis of semi-structured interviews, indicating that eighteen factors influence military resilience in emergencies. These factors were organized into seven main categories (Figure 1). This summary implies that the study aims to identify and categorize key elements contributing to resilience, which can be critical for developing training or support systems for military personnel.

Individual characteristics

This category is derived from discussions about personal characteristics and coping mechanisms influencing resilience. Individual factors encompass personal characteristics and coping strategies that affect resilience. These factors were identified through thematic analysis of participant interviews, highlighting how unique personal experiences and traits contribute to resilience in stressful situations. One participant said: “I always try to focus on what I can control. My previous disaster experiences taught me to stay calm and think clearly.”

Personality differences

Military personnel mentioned characteristics such as patience, compassion, sacrifice, selflessness, responsibility, empathy, and altruism. One participant shared, “During the earthquake and the call for the mission, despite severe family problems, I went on the mission and stayed there for several days to help” (Participant [P] 4).

Cognitive-behavioral differences

Military personnel referred to characteristics such as interest in teamwork, commitment to work, responsibility, ability to cope with challenges, work ethic, decision-making power, appreciation, dutifulness, ability to manage situations during crises and high presence of mind, which fall under the category of individual cognitive-behavioral abilities. They also mentioned characteristics such as having high physical readiness, robustness, sufficient skills, high speed of action, work experience, management ability and communication skills, which refer to the cognitive flexibility of military personnel. These qualities create a sense of meaning and coherence, and their content includes active learning, being in search of new experiences, actively testing and having an open and highly accurate mind. “I learned to control my emotions and feelings in emergencies and disasters, control myself at that time, and help. I learned and applied this in my own life, too. When something comes up, I gather myself and try to use my abilities to solve that problem or do whatever I can” (P8).

Psychological characteristics

Employment in special occupations such as military occupations and in special situations such as presence at the scene of emergencies and disasters is one of the stressful experiences that threatens the mental health of individuals, which is followed by PTSD and job burnout for personnel. This category is named based on insights related to mental health, emotional regulation, and stress management strategies. Psychological factors refer to mental health aspects, including stress management and emotional regulation. Participants indicated that their ability to manage anxiety and maintain a positive mindset significantly affected their resilience. One participant said: “Maintaining a positive outlook was crucial for me. I learned that if I could keep my mind clear, I could handle anything that came my way.”

Mental health

I always feel stress and anxiety when starting a mission that whether my family and I are safe or not (P15).

Posttraumatic stress

After the earthquake, I had nightmares for several consecutive nights and woke up feeling like the rubble had fallen on my head (P3).

Job burnout

I feel that after 20 years of service, I no longer have the initial motivation and energy and get tired earlier than before, and my tolerance has decreased (P10) .

Structural and organizational characteristics

Structural and organizational characteristics play a significant role in the resilience of military personnel. This category includes stringent regulations, pre-emergency, disaster planning, and preparedness. This category reflects the influence of military structure, leadership, and organizational support on resilience. This subgroup includes elements related to the military structure and organizational support systems that facilitate resilience. Insights from interviews revealed that effective communication and leadership play vital roles in preparing personnel for natural disasters. One participant said: “Our unit had a solid plan, and knowing that gave us confidence. Good leadership made us feel supported during the crisis.”

Stringent regulations

In the content analysis conducted, military personnel referred to strict organizational regulations, such as the chain of command and its application to all matters, low or undefined mission allowances, failure to timely replace effective and fresh forces, recruitment and training of skilled and experienced personnel, attracting active personnel interested in providing services in emergencies and disasters, and ensuring the safety of personnel during missions. One participant stated: “Everything in this organization is dictated; no specific laws exist. It means whatever the commander says is what it is. I have been in all crises without receiving a single Rial of mission allowance” (P22).

Pre-emergencies, disasters planning and preparedness

The preparedness of military personnel before emergencies and disasters include developing and implementing necessary training, dispatching specialized and trained personnel related to emergencies and disasters, ensuring food and welfare facilities and providing up-to-date equipment. Personnel indicated, “It seems that the organization just needs to send us to be present; it doesn’t matter what our specialty is or whether we have received training” (P17).

Stress-inducing agents

Throughout their lives, military personnel encounter various stressful events and factors. Employment in military jobs, especially under specific conditions such as being present at the scene of emergencies and disasters, is one of the stressful experiences individuals face. Many factors exacerbate the effects of these stress-inducing agents. This category captures external pressures that challenge resilience, as articulated by participants. Stress-inducing agents are external pressures that can negatively impact resilience. Participants discussed how unpredictable situations, such as sudden evacuations or lack of resources, heightened stress levels and challenged their coping abilities. One participant said: “The uncertainty was the hardest part. When we didn’t know what was happening next, it created a lot of anxiety among us.”

Initial reactions

The resilience process is triggered by an individual’s initial response to an incident or emergency. In emergencies and disasters, victims and those around them generally do not maintain an appropriate mental-emotional balance; they tend to be demanding and highly irritable. In such situations, military personnel face traumatic and distressing injuries and experience indirect trauma. One participant noted: “For a long time, I couldn’t laugh from the bottom of my heart; the image of the half-destroyed bodies we pulled out from under the rubble kept coming to my mind” (P15).

Unstable working conditions

Characteristics of being in emergencies and disasters include unpredictable situations and poor inter-organizational management and coordination. Working under unstable weather conditions, such as floods or earthquakes, complicates rescue efforts. One participant noted: “Everyone was playing their tune, and there was no unified command; for example, the flood barriers we built yesterday were destroyed by another organization with a bulldozer the next day” (P24).

Insufficient preparedness for response

In responding to incidents during emergencies and disasters, having adequate and appropriate infrastructure, space, facilities, and equipment is essential. One participant stated: “In the earthquake and those poor sanitary conditions, having access to trailers and pre-fabricated bathrooms and toilets became the people’s wish” (P7).

Resources and support

Interpersonal relationships with expressions of positive emotions, affirmation and validation of the individual’s beliefs, and seeking help from others help the individual. In this category, two items were identified: Support and spirituality. The content of this category includes having access to and receiving support through relationships with family, friends and significant people in life, the community and colleagues in the workplace. This category represents material resources and emotional support systems identified as crucial for coping. Resources and support include tangible resources (like equipment) and emotional support from peers and family. The data indicated that access to resources significantly mitigated stress and enhanced resilience. One participant said: “Having the right gear made a huge difference. Knowing my family was safe helped me focus on my duties without worrying.”

Supportive factors

In the content analysis, military personnel referred to the supportive role of family members, friends and colleagues in reducing stress. The nature of work during emergencies and disasters is such that services are provided in a group setting, especially during rescue operations and when dealing with many injured people. For this reason, collective support strengthens the group, facilitates service delivery and reduces stress. One participant noted: “In those special circumstances, I couldn’t do much work and was confused, but then I talked to my brother, and he helped and calmed me down” (P19).

Family support

Emotional ties among family members are strengthened through shared recreation and leisure time, fostering a sense of connection. Effective communication involves the exchange of thoughts, opinions and information, which is essential for problem-solving and managing relationships. Support encompasses the perception that comfort is available from others and can be provided to them, including emotional, tangible, instrumental, informational and spiritual support. Closeness is characterized by love, intimacy and attachment, while nurturing reflects the parenting skills contributing to healthy development. Additionally, adaptability refers to the ease with which individuals adjust to changes associated with military life, including flexible roles within the family. These factors are crucial in enhancing resilience among personnel and their families.

Social support

This support includes emotional, informational and practical assistance from family, friends, and community members. Social support can help individuals cope with stress and adversity by providing a sense of belonging, validation, and encouragement. Access to community resources, such as mental health services, educational programs and recreational activities, can enhance resilience. Communities that provide support systems, such as counseling services, peer support groups, and skill-building workshops, empower individuals to develop resilience and cope more effectively.

Organizational support

The most important forms of organizational support that organizations should ensure for military personnel including organizational rewards, favorable job conditions, assistance to military personnel in performing tasks efficiently and managing stressful situations, and support from their commanders.

Colleagues support

Emotional support from colleagues is essential for military personnel who face the unique stresses of their roles. This type of support encompasses empathy, understanding and encouragement during challenging times. Informational support, which involves sharing knowledge, advice and resources, is also vital in military settings. This support can include guidance on coping strategies, operational procedures and mental health resources. Colleagues often provide valuable insights based on their experiences, enabling others to navigate difficult situations more effectively. Studies have shown that access to informational support correlates with better mental health outcomes and increased resilience among military personnel. Practical support is another critical component, encompassing tangible assistance such as help with tasks, sharing workloads, or providing logistical aid. In the military, where teamwork is paramount, practical support can significantly alleviate stress and enhance operational effectiveness. For instance, when team members assist each other with duties or share resources, it fosters a collaborative environment that strengthens resilience. Building a supportive culture within military units is essential for maximizing the benefits of colleagues’ support.

Spiritual factors

Military personnel believe that trusting in God and entrusting themselves to Him makes it easier to endure emergencies, disasters, and difficult situations. “During the mission, I do the tasks for the sake of God and always trust in God (P21).

Sense of purpose and meaning

Spirituality often gives individuals a profound sense of purpose and meaning. A clear sense of purpose can motivate personnel working in high-stress environments, such as military or healthcare settings. It helps them understand the significance of their roles and responsibilities, which can foster commitment and dedication. This sense of purpose can act as a protective factor, enabling individuals to navigate challenges and maintain their morale even in difficult circumstances.

Coping mechanism

Spiritual practices, such as prayer, meditation, and reflection, can serve as effective coping mechanisms for personnel dealing with stress and trauma. These practices can help individuals manage their emotional responses, reduce anxiety and promote relaxation. Research has shown that spirituality can enhance emotional regulation and provide comfort during times of distress, leading to improved mental health outcomes. These coping strategies can be particularly beneficial in high-pressure situations where personnel may experience overwhelming emotions.

Social support and community

Spirituality often fosters a sense of community and belonging, which is crucial for resilience. This sense of community can alleviate isolation and loneliness, which are common in high-stress professions. Support from peers who share similar spiritual beliefs can enhance coping strategies and provide a safe space for discussing experiences and emotions related to their work.

Moral and ethical framework

Spirituality can offer personnel a moral and ethical framework that guides their actions and decisions, particularly in high-stress situations. This framework can help individuals navigate the complexities of their roles and the moral dilemmas they may face, reinforcing their sense of integrity and accountability. A clear set of values rooted in spirituality can bolster resilience by giving personnel the confidence to make difficult decisions and maintain their sense of self in challenging environments. This moral grounding can also contribute to posttraumatic growth, allowing individuals to find meaning in their experiences and emerge stronger.

Adaptation processes

These processes are related to the individual’s recovery from an incident or unpleasant experience, using individual capacities and external support and achieving positive outcomes in work and life if successful. The content analysis divided the results into three subcategories, which are discussed separately below. This category is named for individuals’ strategies to adjust to challenges, emphasizing flexibility and learning. Adaptation processes refer to individuals’ strategies to adapt to challenging situations. Participants stressed the importance of flexibility and learning from experiences as key components of their resilience. Participant Quote: “Every disaster teaches you something new. Adapting quickly became second nature after a few experiences.”

Smart adaptation

Military personnel referred to characteristics such as self-awareness, self-esteem, a sense of being helpful, and a sense of humor. “Just the fact that a helpless and suffering person thanks you and prays for you and your family is the highest reward possible (P23).

Cognitive strategies