Volume 11, Issue 2 (Winter 2026)

Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2026, 11(2): 115-128 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1399.187

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yaghmaei S, Ebrahimian A, Pourteimour S. Nurses’ Perspectives on Gender Equality Policies During the COVID-19 Response Phase. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2026; 11 (2) :115-128

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-719-en.html

URL: http://hdq.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-719-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

2- Spiritual Health Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. ,ebrahimian.aa@gmail.com

3- Patient Safety Research Center, Clinical Research Institute, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran. & Nursing Care Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

2- Spiritual Health Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. ,

3- Patient Safety Research Center, Clinical Research Institute, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran. & Nursing Care Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 566 kb]

(529 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1368 Views)

Full-Text: (201 Views)

Introduction

Apandemic is defined as an epidemic that spreads across multiple countries or continents, affecting a large number of people. It represents a significant threat to global health, often leading to widespread morbidity and mortality, as well as social and economic disruptions. Historical examples include the black death and the Spanish flu, with contemporary instances, such as COVID-19 [1, 2].

Nurses play a pivotal role in shaping pandemic response strategies through their frontline experiences, leadership, and adaptability. Their contributions are essential in developing frameworks that enhance healthcare systems’ resilience during crises [3, 4]. Nurses have developed structured response models, such as the 5A model (alarm, assessment, adaptation, amplification, affect), which outlines their sequential responses to crises, like COVID-19. This model serves as a theoretical foundation for future pandemic preparedness [3]. Nurse leaders have demonstrated effective leadership by anticipating needs, fostering collaboration, and innovating care practices. Their experiences during the pandemic highlight the importance of involving nursing professionals in policy development and emergency preparedness planning [4].

The integration of gender mainstreaming into pandemic response strategies significantly enhances their effectiveness by addressing the unique vulnerabilities and needs of different genders, particularly women and girls. Gender mainstreaming ensures that pandemic responses are equitable and inclusive, which is crucial for mitigating the disproportionate impacts of health crises on women. This approach not only improves health outcomes but also supports broader social and economic stability during pandemics [5, 6]. Gender-sensitive policies, such as those implemented in Kerala, India, have proven effective in addressing the specific needs of women during the COVID-19 pandemic. These policies included economic relief packages, support for mental health, and measures to combat gender-based violence, demonstrating the importance of gender considerations in policy-making [7]. In contrast, the lack of gender-sensitive policies in Uganda led to increased gender inequalities, highlighting the need for proper gender analysis in designing response measures [5].

The presence of women in decision-making roles has been linked to more gender-sensitive policy responses. Countries with higher female representation in government taskforces, such as those led by women, tend to implement more inclusive and effective pandemic responses [8]. However, women are often underrepresented in decision-making positions, which limits the integration of gender perspectives in pandemic planning and response [8, 9]. An intersectional approach to pandemic response, which considers the overlapping impacts of gender with other social determinants, is crucial for addressing the diverse needs of populations. This approach can help mitigate the compounded vulnerabilities faced by women, particularly those from marginalized communities [6, 10].

Despite the benefits of gender mainstreaming, many pandemic responses have failed to adequately incorporate gender perspectives, resulting in missed opportunities to address gender disparities effectively [11].The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for a gender-responsive, intersectional approach to future health crises, emphasizing the importance of integrating gender considerations into all levels of policy-making and implementation [10, 12].

Given the intricacy and multidimensionality of gender justice, a comprehensive examination of this concept necessitates a thorough investigation within the relevant field. In this regard, qualitative studies of an in-depth nature offer a profound understanding of the subject matter under scrutiny. As such, the present research employed a qualitative approach to explore the nature of gender justice as experienced by nurses amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research has merely dealt with gender justice in nursing and policymaking during various crises separately, and considering the continuation of the COVID-19 pandemic and the possibility of similar ones in the future, it is necessary to make policies based on gender equality from the perspectives of nurses working in COVID-19 units. Given the complexity and multidimensionality of concepts, such as gender justice, a thorough investigation of said concepts within the desired field is imperative. In this regard, qualitative studies with an inherent depth are particularly valuable as they offer an intimate and insightful portrayal of the field under scrutiny. This study explored nurses’ perspectives on gender equality policies during the response phase of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The unique contribution of this study lies in its focus on frontline nurses’ perspectives regarding gender equality specifically within the context of management policies and resource allocation during the COVID-19 response phase. While previous research has broadly examined gender disparities in healthcare or workplace environments, this study highlights how these inequalities manifested in real-time crisis management—a context that exposed systemic gaps more starkly. This study breaks new ground by systematically examining structural gender inequities in crisis management during COVID-19, revealing how institutional policies perpetuated disparities despite formal equality measures. Through in-depth qualitative analysis, this study uncovered the lived experiences of structural gender inequities in pandemic crisis management, exposing how organizational cultures and hidden power dynamics systematically disadvantaged female healthcare nurses.

Materials and Methods

Study design and settings

This study was conducted using a qualitative content analysis approach in 2020-2021. In this study, the policy based on gender equality from the perspective of Iranian nurses in the COVID-19 units was analyzed using content analysis through Graneheim and Lundman model [13]. During the fieldwork phase, in-depth, face-to-face, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with 14 nurses working in COVID_19 units, with each interview lasting between 30 and 60 minutes. Participants were selected using purposive sampling, and data collection continued until data saturation was achieved. All interviews were recorded. A total of 14 participants were selected through purposive sampling to ensure representation of diverse and relevant perspectives. This number was deemed sufficient for generating rich qualitative data within the scope of the study. Data saturation, the point at which no new themes or insights emerged, was used to determine the adequacy of the sample size. Saturation was reached by the 12th participant, and the final two interviews confirmed the consistency and completeness of the identified themes.

Participants

In selecting participants, maximum diversity was considered in terms of age, gender, and marital status (Table 1).

Inclusion criteria were at least two years of clinical work experience, employment in one of the COVID-19 units, educational hospitals and medical centers in Iran, and participant’s desire to participate in the study. During the nurses’ shifts, the researcher approached the nurses eligible to participate in the study and arranged to meet with those who wished to cooperate after their shifts. The location and time of the interviews were selected according to the participants’ preferences; however, most interviews were conducted in restrooms after work shifts. The guiding questions for the interviews at this phase included the following. As the study progressed, data collection, simultaneous analysis, and the formation of categories influenced the direction of subsequent interviews:

● What were your biggest challenges at work during COVID-19?

● How do you perceive the effect of nurses’ gender differences during the COVID-19 pandemic on managers’ decisions?

● Can you provide an example of a policy that you found unfair or gender-based?

● What comes to mind when you come across the word gender justice in nursing policy?

● Was there a difference in access to protective equipment (e.g. masks, PPE) between male and female nurses?

● Did support policies (e.g. leave, psychological counseling) address the specific needs of female or male nurses?

● How do you see the performance of nursing managers in the COVID-19 crisis?

In addition, exploratory questions were also used to understand the interviewees’ experiences better.

As the interviews progressed, questions were grouped by topic to guide the conversation and help explore various dimensions of the topic:

1. Background and experience:

A. Can you tell me about your role and responsibilities during the COVID-19 response phase?

B. How long have you been working in the nursing profession?

2. Perceptions of gender equality in the workplace:

A. How would you describe the state of gender equality in your workplace during the COVID-19 response?

B. Did you notice any differences in how male and female nurses were treated or expected to perform during the pandemic?

3. Awareness and understanding of gender equality policies:

A. Were you aware of any gender equality policies implemented during the COVID-19 response?

B. How were these policies communicated to you and your colleagues?

C. In your view, were these policies effectively implemented?

4. Impact of policies on work and well-being:

A. Did gender equality policies influence your work conditions (e.g. shift assignments, workload, decision-making involvement)?

B. How did these policies affect your physical and mental well-being, if at all?

C. Can you describe any specific incidents where you felt supported or unsupported due to your gender during the pandemic?

5. Challenges and disparities:

A. Were there any specific challenges you faced as a nurse during the pandemic that you believe were related to gender?

B. Were caregiving responsibilities outside of work (e.g. family, children) considered or supported during the response phase?

6. Institutional support and leadership

A. How did leadership in your organization respond to gender-related concerns during COVID-19?

B. Do you feel your concerns or suggestions were heard and addressed?

7. Suggestions for improvement:

A. What do you think could have been done differently to promote gender equality more effectively during the COVID-19 response?

B. What recommendations would you give to health institutions for future emergency responses regarding gender equality?

8. Closing question:

A. Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience related to gender equality during the COVID-19 response?

Data analysis

At the end of the interviews, the participants were asked to speak freely in case of other points regarding the interview. All the interviews were recorded using a smartphone after taking the participants’ permission and were transcribed into written text immediately. The data were analyzed using content analysis through the conventional method and Graneheim and Lundman’s five-step conventional content analysis approach. The methodology applied by Gernheim and Lundman for data analysis was comprised of a sequential series of five distinct steps. First, following each interview, the transcriptions were meticulously scrutinized by reading them repeatedly, line by line and paragraph by paragraph, aimed at obtaining a comprehensive comprehension. Then, the primary codes were extracted. Afterward, based on similar codes, sub-categories, categories, and themes were formulated. The initial interview was then categorized, and the subsequent interviews aided in finalizing the primary category. Finally, an endeavor was undertaken to ensure the utmost homogeneity within categories and the most remarkable heterogeneity between categories [13].

Graneheim stated, “If the aim is to describe participants’ experiences of ordinary phenomena and the data is concrete and close to the participants’ lived experience, it may be wise to limit the analysis to categories at a descriptive level. If the analytic process continues too far, the results can become so abstract and general that they could fit into any context, and thereby say nothing about the participants’ unique experience in that situation” [13].

The preliminary codes were categorized and labeled based on their conceptual similarity (sub-categories). The sub-categories were compared and placed under main categories, which were more abstract (categories). The main categories were categorized under a more abstract concept (theme).

Rigor and reliable data

In order to ascertain the integrity of the data, four fundamental criteria—credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability—were employed, as delineated by Polit and Beck [14]. The investigator engaged in an extended sojourn at the various research sites, which facilitated the establishment of rapport with the participants and a deeper comprehension of the contextual factors at play. The participants’ feedback was additionally employed to authenticate the data and coding; subsequent to the coding process, the transcripts of the interviews were returned to the participants to confirm the fidelity of the codes and their corresponding interpretations. Moreover, the participants endeavored to represent a broad spectrum of diversity in terms of age, gender, experience, educational attainment, and professional settings. The supervisors meticulously examined the transcripts derived from the interviews. In conjunction with the supervisors, the derived codes and classifications were presented to several individuals well-versed in the nursing domain and qualitative research methodologies; these were subjected to thorough scrutiny. A high level of consensus was observed regarding the results extracted from the analysis. Ultimately, the categories and excerpts from the interviews were translated into English by a qualified translator and subsequently refined by a professional editor.

Results

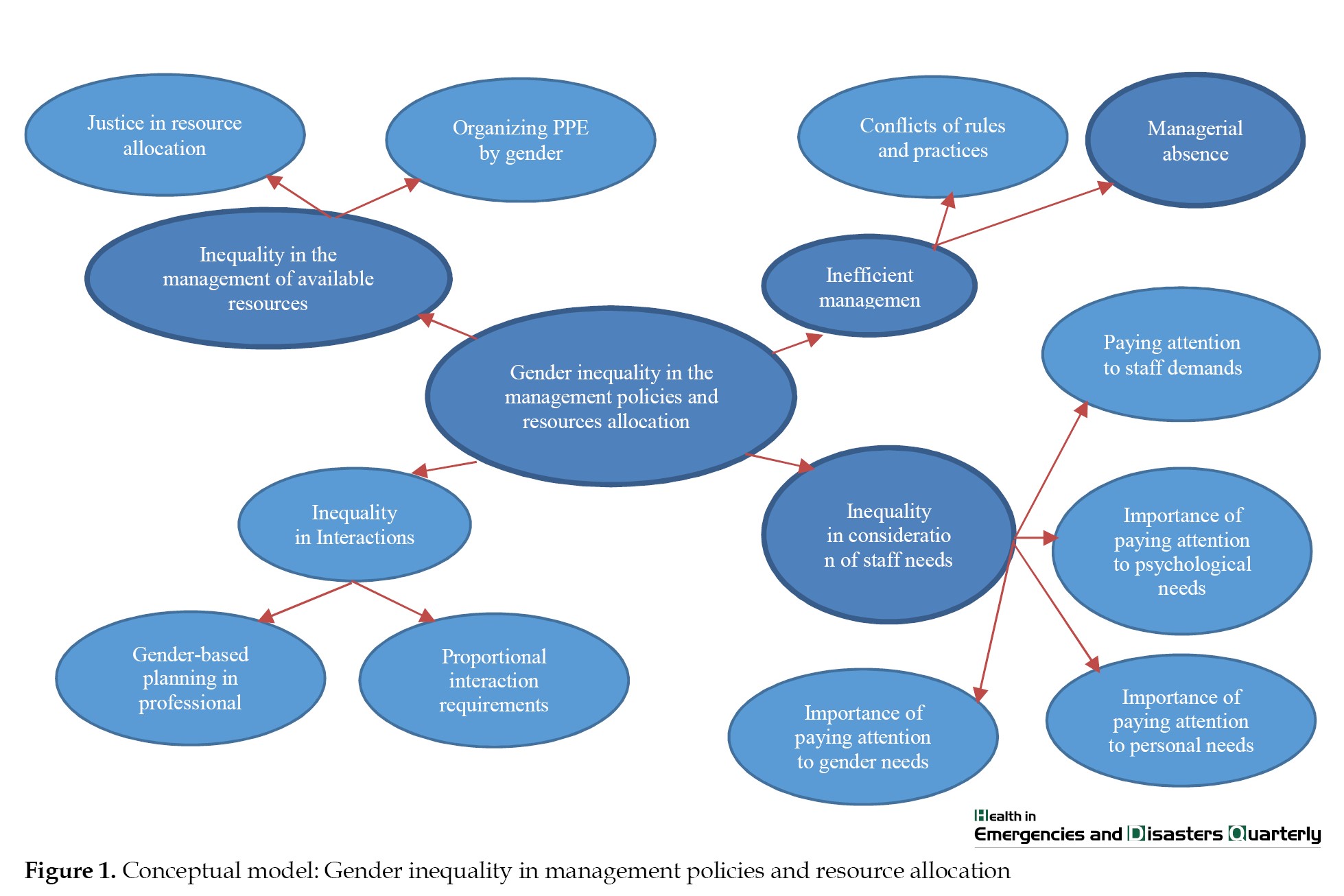

The study was conducted with a cohort of 14 nurses who were working specifically in COVID-19 units, six of whom were identified as male. The initial analysis of the interviews led to the acquisition of 175 codes. The participants’ responses to the research question were organized into a main theme and its associated categories. Ultimately, the main theme was identified as “gender inequality in management policies and resource allocation,” with four categories labeled as “inefficient management,” “inequality in interactions,” “ inequality in the management of available resources,” and “inequality in consideration of staff needs” (Table 2).

The conceptual model of the acquired data is illustrated in Figure 1. This framework may serve for the subsequent purposes:

● Qualitative research on gender justice in healthcare management

● Policy analysis and development to promote equitable work environments

● Organizational audits focused on gender-sensitive planning and resource distribution

● Educational tools for nursing administration and gender studies

The main categories extracted in the present study, along with examples of the participants’ quotations related to the concepts, were as follows:

Inefficient management:

1. Managerial absence

2. Conflicts of rules and practices

As subcategories, the first category identified was inefficient management, which was derived from managerial avoidance and conflicts arising from incongruent rules and practices. Furthermore, the related concepts encompassed the dwindling presence of field managers, diminished responsiveness to challenges encountered by wards, non-adherence to a statute mandating the allocation of working hours based on work experience, marital status, and the number of children, the unavailability of a nurse of the same gender to provide exceptional care to patients, and a disparity in workload volume/type in relation to nurses’ gender and abilities.

In Iran, the provision of nursing care for female patients is predominantly carried out by female nurses, a practice shaped by prevailing cultural norms. Consequently, in cases where the female patient population surpasses the male patient population within the inpatient department and the female nurse’s counterpart is a male nurse, it results in an escalation of workload for the female nurse.

When female nurses were engaged in extended and frequent shifts, particularly those who were married and had a spouse and children, their attention toward their patients was diminished as a result of the substantial workload and obligations. Numerous statements articulated by the study participants with regards to the aforementioned concepts were as follows:

a. Concerning the concept of diminishing presence of field managers, one of the participants stated that: “I can almost say that the presence of some managers, in particular those who do most office work, not the ones with whom we have direct contacts, was deficient during this crisis. Practically, neither senior supervisors nor those whom I saw frequently before, like the infection control supervisors, who used to be around and whose main job should now be training other supervisors and generally the senior manager, were seen in the COVID-19 unit during this pandemic at all” (27 years old, female).

b. One of the participants reiterated the reduced responsiveness to challenges facing wards: “Due to the critical situation that occurred, we faced lots of problems in the wards. In these cases, we often used to call the supervisors, but unfortunately, the cooperation was not what it should have been” (27 years old, male).

Another nurse also stated, “Most nursing managers only insist that the work should be done anyway. Once the number of patients was very high and the workload was too high, they used to say that all work must be done anyway, and there was no way. They were adding fuel to the fire. However, at least it would have been better for them to give us a hand and get help from nurses from more private wards or be present in the ward themselves” (27 years old, female).

c. Regarding failure to comply with a statute for allocating working hours based on work experience, marital status, and the number of children, one of the participants added that: “During this time, shifts were very long, but the important thing was that it could become challenging for me if I was married, and I could not take care of the patients properly when I was on a shift” (30 years old, female).

One other participant also said: “Female co-workers who had small children had similar shifts to ours, but they were constantly worried and even cried during shifts, and we had to do their jobs as well” (32 years old, male).

d. Regarding the absence of a nurse of the same gender to provide exceptional care to patients, one of the participants stated that: “In our ward, as a COVID-19 unit, the patients’ families were not allowed to accompany them to help with some work. During most shifts, my co-workers and I were both men, and most of our patients were women, so we had hard times doing some procedures, such as bladder catheterization and intramuscular injection of drugs. The supervisors also did not help us” (28 years old, male).

Another nurse additionally maintained: “For example, one day, my co-worker was male. We divided the patients according to the care volume because we had to do so. My co-workers’ patients were women, so I had to do some of their care, and my workload multiplied” (30 years old, female).

Inequality in interactions

1. Gender-based planning in professional interactions

2. Proportional interaction requirements

The second category of the study was centred on the topic of “inequality in interactions”. This was derived from the proportional interaction requirements and gender-based planning in professional interactions. The category encompassed various concepts, such as respect and the role of gender in administrative interactions, privacy of nurses, enhancing caring relations and empathy during a crisis, and interactions based on an understanding of needs. Within the context of Iran, female nurses exhibit a tendency to engage in regulated interactions with male nurses and other individuals, influenced by religious considerations. Consequently, instances where their privacy is disregarded lead to feelings of insecurity. The study participants provided several statements based on the aforementioned concepts:

Regarding respect and the role of gender in administrative interactions, one of the participants noted that: “Our cooperation with different people was based on their moral characteristics in terms of gender. With a female co-worker, especially in terms of age, particularly when we were the same age, we could have a better and closer relationship” (27 years old, female).

Another participant said: “We were usually more comfortable with co-workers, who had the same gender, but we also had no problem with male counterparts, and we used to try to maintain respect at the time of crisis” (37 years old, female).

Regarding nurses’ privacy, one of the participants said, “There should always be a framework for relationships, but in any case, my security should never be violated.” (30 years old, female).

Moreover, another participant said, “During the COVID-19 crisis, we were all under much stress, but we would not like anyone to invade our privacy, and that was annoying” (28 years old, male).

One participant added regarding the increase in caring relationships and empathy during a crisis: “The difference between the COVID-19 crisis and normalcy was that our relationships became better and friendlier. The managers also became more intimate with us, and this helped us get through the difficult situation better” (28 years old, male).

Another participant said, “It was true that the number of patients increased and we were terrified of getting sick, but some nursing managers and supervisors became more intimate with us, even by talking on the phone, and showed more compassion, which was good and inspiring” (37 years old, female).

Regarding interactions based on an understanding of needs, a nurse stated, “I have a small child, and my parents are also sick, so I am always worried about transmitting the disease to them in shifts, and I do not focus on the care I provide, but someday Ms. Akbari (one of the supervisors) came to our ward and found out that I was distraught, so she talked to me and reassured me, and that was very good” (34 years old, female).

Inequality in the management of available resources:

1. Organizing personal protective equipment (PPE) by gender

2. Justice in resource allocation

The third category was related to the inequality in management of available resources, mined from organizing PPE by gender and justice in resource allocation, including concepts, such as medical and protective requirements based on gender, facilitated access to PPE, and gender-appropriate protective covers. Some statements provided by the participants based on the given concepts were as follows:

Considering the concept of medical and protective requirements based on gender, most participants in this study said, “Men care less about personal protection coverage than women, and they are more courageous in providing clinical care in COVID-19 wards” (37 years old, female).

Men’s valiant actions in tending to individuals afflicted with COVID-19 may pose a risk to their own well-being; nevertheless, it enhances their proficiency in attending to covid-19 patients.

One of the nurses also said, “At the onset of this crisis, due to severe shortages of PPE, they were rationed in the wards, and the head nurses were responsible for distributing the equipment between the nurses and other members of the treatment teams. Due to the cover we had on, in addition to the PPE, they got wet very quickly because of excessive sweating and had to be replaced sooner, but the number of our equipment was equal to that of men’s” (30 years old, female.

Regarding facilitated access to protective equipment, one participant said, “The head nurses, who were male, were much better at distributing protective equipment among the staff and better managing their shortages, but female head nurses and managers were more sympathetic to the staff and nurses. However, access to PPE was initially our biggest concern during the COVID-19 pandemic” (32 years old, male).

Regarding the concept of gender-appropriate protective covers, one of the participants stated, “Our covers were the same during the COVID-19 crisis because personal protective clothing was very similar, and there was no difference between men and women. Of course, we hardly knew each other, and communication was difficult” (27 years old, male).

Inequality in consideration of staff needs

1. Paying attention to staff demands

2. Importance of paying attention to psychological needs

3. Importance of paying attention to personal needs

4. Importance of paying attention to gender needs

The fourth category focused on the topic of disparity in fulfilling staff needs. It was drawn from considering the requirements of staff, their psychological needs, and their gender-specific necessities. The gender-related demands included a range of ideas, like suitable emotional and physiological needs based on gender and unique distinctions. The participants articulated several statements based on these aforementioned concepts, which included the following:

a. Concerning paying attention to gender-appropriate emotional needs, a participant said, “I have often experienced that the authorities have been less strict with men and have had higher expectations of us as women, making us resentful with this gendered view” (30 years old, female).

The occupation of nursing aligns closely with the emotional and nurturing characteristics traditionally associated with women, leading nursing supervisors to potentially have higher expectations of female employees in the nursing profession. The establishment of such anticipations may appear justifiable as it pertains to the psychological attributes exhibited by female nurses. However, disparities arise in the workplace where both male and female nurses are deemed equivalent in their occupational duties and remuneration, thus necessitating a mutual enhancement of their favourable demeanour when tending to patients.

b. In terms of paying attention to individual differences, one of the participants said, “In my opinion, the main problem facing nursing managers was that they had the same expectations from everyone, and during this crisis, they only paid attention to the performance of nursing duties and care and did not consider nurses and their abilities at all" (27 years old, male).

c. Regarding the concept of paying attention to physiological differences, a female nurse said, “Of course, I am not saying that women are less capable, but gender should be considered in the arrangement of shifts and wards. For example, I was on many shifts with a male co-worker; he used to help me a lot, did many activities that we could not do, and in general, it sometimes felt excellent to have a male co-worker in the ward” (30 years old, female).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed several primary causes of inefficient management in nursing, significantly impacting healthcare delivery. Key factors include inadequate support for nursing staff, ethical dilemmas in resource allocation, and the psychological toll on healthcare professionals. These issues collectively hinder effective management and care provision during crises.

Inadequate support for nursing staff

● Nurse managers often focused on logistical challenges, such as staffing and training, while neglecting the mental well-being of their teams [15].

● There was a critical shortage of PPE and other resources, forcing nurses to make difficult ethical decisions regarding patient care [16].

Ethical dilemmas

● The allocation of scarce resources, such as ventilators and ICU beds, raised ethical concerns about fairness and equity in patient care [16].

● Nurses faced the challenge of balancing personal safety with professional obligations, leading to moral distress [16].

Psychological impact

● The pandemic resulted in significant emotional strain on nurses, contributing to burnout and mental health issues [17].

● Support systems, including mental health resources, were often insufficient, exacerbating the challenges faced by nursing staff [18].

Conversely, some argue that the pandemic has also fostered resilience and innovation in nursing management, prompting the development of new strategies and collaborative practices that may enhance future healthcare responses.

The present study aimed to explore gender equality policies from the perspectives of Iranian nurses working in pandemic situation. The study findings accordingly shed light on gender inequality in the management policies and resource allocation. Several themes were also developed, including inequality in management, inequality in interactions, inequality in management of available resources, and inequality in consideration of staff needs. In the meantime, some concepts were extracted, such as conflicts of rules and practices, gender-based planning in professional interactions, organizing PPE by gender, and the importance of paying attention to psychological, personal, and gender needs, which will be discussed below.

Inefficient management was one of the issues affecting the nurses’ views. Among these issues was the managerial absence; for example, reduced responsiveness to challenges facing the wards, as expressed by the interviewees. The managerial absence was also a new concept that had not been explored in nursing and other fields. Another issue was the diminishing presence of field managers. For example, the study participants mentioned the absence of the infection control supervisor in the wards for direct control and training. In their study, Hesselink et al. also reported that the presence and availability of nurse leaders during daily work were significant from the perspectives of nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs) [19]. McSherry et al. also found that excellence in nursing care could occur if nursing managers and leaders had responded to the complexities of reforms and changes [20], which was in line with the results of the present study.

The findings of the current study also highlighted a failure to adhere to a particular statute concerning the distribution of working hours, taking into account factors, such as work experience, marital status, and the number of children. This serves as an illustration of conflicts arising from discrepancies between rules and actual practices. In this respect, Hoffman et al. established that nurses working 12-hour shifts were younger, less experienced, and more stressed than their co-workers who were working 8-hour shifts. Once the differences in nursing experience were controlled, similar stress levels were observed in the nurses [21].

Wang et al., in their study conducted in the nursing ward of a hospital, practically implemented sustainable support, dynamic human resource allocation, organization of pre-service training, monitoring of main stages of work, formulation of positive incentive methods, as well as the use of medical equipment [22]. They reported that such strategies had significantly boosted the capacity of the hospital nursing team to deal effectively with the COVID-19 pandemic Additionally, Wang et al. concluded that the reasonable allocation of the nursing workforce along with other strategies could ensure safe, effective, timely, regular, and sustained centralized treatment of COVID-19 [22].

The imbalance in volume/type of work and nurses’ gender and abilities, also influenced their views toward policymaking in this study. Galbany-Estragués and Comas-d'Argemir further showed that time pressure had separated clinical practices of nursing care from the context of nursing theory [23]. Therefore, in case of a mismatch between workload and care with the nurses’ gender and abilities, inefficient care and error would be observed. Sasa et al., in his study, correspondingly revealed that a gender-balanced workforce, combined with unique care concepts, could strengthen the nursing profession and optimize abilities to provide customer services [24].

Interactions were also among the categories extracted in this study. In this line, Utoft highlighted three factors—communication, leadership commitment, and holistic assessment—that can improve gender equality in organizations [25], which is consistent with the findings of the present study. The concept of respect and the role of gender in administrative interactions were similarly clarified in the present study. In this regard, Zanielm et al. found that most nurses identified gender as a significant factor in nurses’ interactions, with women being more likely than men to experience interprofessional gender biases [26]. However, Aguirre et al., examining gender patterns of interactions in an interprofessional health care network, reported that network members were likely to communicate with men and women without any preferences [27]. This could be due to the cultural differences between the two study environments. Accordingly, in the study by Alghamdi et al., nurses, regardless of gender, showed job satisfaction and a greater understanding of transformational leadership style when their managers were male [28].

The study participants also reported an increase in caring relationships and empathy during crises, particularly in the relationships among managers, staff, and co-workers. Unfortunately, no studies were found assessing these two variables in relationships between nurses; thus, further research is suggested.

The management of available resources was another viewpoint among the nurses about policymaking during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this respect, Bambi et al. stated that long hours of using PPE were associated with adverse consequences, such as discomfort, fatigue, and skin damage for most nurses working in COVID-19 ICUs. Nursing managers were thus required to adjust day and night shifts, taking into account the maximum duration of PPE use [29], which was in agreement with the findings of the present study.

One of the concepts related to the management of available resources was gender-appropriate protective cover. The inequitable and disproportionate utilization of PPE emerged as a prominent indicator of gender disparity among nurses amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, the presence of gender inequality persisted despite the equitable distribution of PPE, attributed to additional factors. Although no study related to this concept was found, Ong et al. reported that using PPE could cause headaches or increase and exacerbate chronic ones in healthcare workers [30]. Therefore, designing PPE based on staff needs and gender is essential to improving their performance and maintaining their physical health.

Although the consideration of staff needs in policymaking was acknowledged in this study, no specific cases were found. Anders et al. established that nurses were rarely involved in policymaking while implementing health policies [31], which could explain why the gender, as well as the physical and psychological needs of nurses, had not been adequately respected.

Although male nurses were less likely to directly report discrimination, 4 out of 6 male participants acknowledged an inequity in the distribution of high-risk shifts in their favor. This study is pioneering in examining the gendered dimensions of PPE distribution during COVID-19, revealing systemic patterns of inequity in resource allocation despite quantitative parity—a critical gap that has been unaddressed in prior literature.

Implications for international contexts and broader health systems

The findings of this study, while rooted in a specific national context, have important implications for international health systems and global health policy. The gendered experiences of nurses during the COVID-19 response highlight the need for inclusive policy design that explicitly considers the diverse needs of healthcare workers based on gender, role, and social position. In broader health systems, this underscores the importance of embedding gender equity frameworks into emergency preparedness and workforce planning. Internationally, the study supports calls from organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations (UN) Women to integrate gender-responsive approaches into health crisis management. The insights may also inform comparative policy development, guiding countries toward more equitable resource distribution, psychosocial support mechanisms, and staffing practices that reflect a commitment to gender justice in healthcare delivery.

Strategies for integrating gender equality into pandemic policy

1. Gender-responsive workforce planning

Ensure staffing policies account for gender-related roles, caregiving responsibilities, and occupational segregation (e.g. female-dominated nursing roles).

Avoid disproportionate workloads for women through equitable shift scheduling and task distribution.

2. Inclusive decision-making

Involve women—especially frontline health workers—in all levels of pandemic planning and policy-making committees.

Establish gender-balanced advisory boards and crisis management teams.

3. Sex-disaggregated data collection & analysis

Collect and analyze data on infection rates, workload, PPE access, and psychological outcomes by gender to identify disparities in real-time.

Use these data to inform targeted interventions.

4. Equitable resource allocation

Distribute PPE, rest spaces, and support services based on actual need, accounting for gender-specific requirements (e.g. fit and comfort of PPE).

Ensure pregnant and breastfeeding healthcare workers have appropriate accommodations and protections.

5. Supportive work policies

Implement family-friendly policies (e.g. flexible hours, parental leave, childcare support) to reduce stress and burnout, especially among female health workers.

Provide psychological support services tailored to gender-related stressors and experiences.

6. Anti-discrimination and harassment protections

Enforce zero-tolerance policies against workplace harassment, with particular attention to gender-based and sexual harassment during crisis conditions.

Create safe reporting channels and protections for whistleblowers.

7. Training and awareness programs

Integrate gender-sensitivity training into pandemic preparedness modules for managers and frontline staff.

Build awareness of unconscious bias and its consequences in health crisis settings.

8. Accountability and monitoring mechanisms

Establish systems to monitor the implementation of gender-sensitive measures throughout the pandemic lifecycle.

Conduct regular audits and evaluations of gender equity outcomes in emergency response operations.

Conclusion

This study highlighted nurses’ perceptions of gender inequality in management policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants identified inefficient leadership, biased resource allocation, and unequal interactions as key barriers. These findings align with global evidence on crisis-driven gender disparities. To address this, we recommend establishing gender-balanced decision-making teams, regular audits of resource distribution, and training for managers on gender-sensitive leadership.

Future research should explore male nurses’ perspectives and evaluate interventions to reduce inequities. Despite limitations (e.g. nurses’ fatigue), this study underscores the urgent need for policy reforms before the next crisis.

The findings revealed that nurses’ perception of managerial inadequacy and leadership gaps during crises significantly undermines workforce morale and erodes trust in institutional policies. Given the demonstrated impact of nursing staff’s perspectives on policy formulation and crisis management efficacy, healthcare administrators must prioritize mechanisms for systematically integrating frontline nurses’ insights into decision-making processes—particularly during emergency response planning.

To advance gender equity in nursing, we propose three critical action domains:

Root cause analysis: Rigorous mixed-methods investigations into structural and cultural determinants of occupational disparities between male and female nurses;

Intervention development: Design and implementation of evidence-based protocols to address identified inequities in resource allocation, leadership opportunities, and workplace interactions;

Impact evaluation: Longitudinal studies assessing the effectiveness of implemented solutions through metrics, including retention rates, promotion equity, and staff satisfaction indices.

These recommendations carry particular urgency as healthcare systems worldwide prepare for future public health emergencies, where equitable workforce management will directly impact pandemic response effectiveness.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the transferability of the findings may be limited, as the experiences and perspectives of nurses are deeply embedded in specific organizational, cultural, and policy contexts. While efforts were made to include participants with diverse backgrounds, the findings may not be generalizable to nurses working in different healthcare systems or cultural settings. Second, the sample size was relatively small, involving 14 participants. Although this number is consistent with qualitative content analysis standards and saturation was achieved, a larger sample could have potentially uncovered additional nuances or divergent viewpoints, particularly across different roles or regions. Third, the study was conducted within a single-country context, which further limits the applicability of the results to other national settings. Gender equality policies and their implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic likely varied across countries, influenced by broader sociopolitical and institutional structures. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted within the specific national and healthcare system framework in which the study was conducted. In addition, the demanding workload and fatigue experienced by nurses during the pandemic crisis may have influenced their willingness to fully disclose sensitive experiences or critical perspectives regarding organizational policies. Some participants potentially self-censored their responses due to concerns about professional repercussions, despite researchers’ efforts to create a safe and confidential interview environment. Also, the study’s focus on a single healthcare setting during an extraordinary crisis period may limit the generalizability of findings to non-crisis situations or different healthcare systems. Future research should consider cross-country comparisons and include broader samples to enhance the understanding of how gender equality is addressed in healthcare crises globally.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran (Code: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1399.187). Coordination was made with Universities of Medical Sciences before sampling. The study objectives and procedure were also explained to the participants, and informed consent was obtained.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.”

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, review and editing: All authors; Data collection: Safura Yaghmaei; Data analysis: Safura Yaghmaei and Sima Pourteimour; Writing the original draft: Abbasali Ebrahimian; Supervision: Abbasali Ebrahimian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their deepest gratitude to the nurses who generously shared their time and experiences during this challenging pandemic period. Their invaluable contributions made this study possible.

References

Apandemic is defined as an epidemic that spreads across multiple countries or continents, affecting a large number of people. It represents a significant threat to global health, often leading to widespread morbidity and mortality, as well as social and economic disruptions. Historical examples include the black death and the Spanish flu, with contemporary instances, such as COVID-19 [1, 2].

Nurses play a pivotal role in shaping pandemic response strategies through their frontline experiences, leadership, and adaptability. Their contributions are essential in developing frameworks that enhance healthcare systems’ resilience during crises [3, 4]. Nurses have developed structured response models, such as the 5A model (alarm, assessment, adaptation, amplification, affect), which outlines their sequential responses to crises, like COVID-19. This model serves as a theoretical foundation for future pandemic preparedness [3]. Nurse leaders have demonstrated effective leadership by anticipating needs, fostering collaboration, and innovating care practices. Their experiences during the pandemic highlight the importance of involving nursing professionals in policy development and emergency preparedness planning [4].

The integration of gender mainstreaming into pandemic response strategies significantly enhances their effectiveness by addressing the unique vulnerabilities and needs of different genders, particularly women and girls. Gender mainstreaming ensures that pandemic responses are equitable and inclusive, which is crucial for mitigating the disproportionate impacts of health crises on women. This approach not only improves health outcomes but also supports broader social and economic stability during pandemics [5, 6]. Gender-sensitive policies, such as those implemented in Kerala, India, have proven effective in addressing the specific needs of women during the COVID-19 pandemic. These policies included economic relief packages, support for mental health, and measures to combat gender-based violence, demonstrating the importance of gender considerations in policy-making [7]. In contrast, the lack of gender-sensitive policies in Uganda led to increased gender inequalities, highlighting the need for proper gender analysis in designing response measures [5].

The presence of women in decision-making roles has been linked to more gender-sensitive policy responses. Countries with higher female representation in government taskforces, such as those led by women, tend to implement more inclusive and effective pandemic responses [8]. However, women are often underrepresented in decision-making positions, which limits the integration of gender perspectives in pandemic planning and response [8, 9]. An intersectional approach to pandemic response, which considers the overlapping impacts of gender with other social determinants, is crucial for addressing the diverse needs of populations. This approach can help mitigate the compounded vulnerabilities faced by women, particularly those from marginalized communities [6, 10].

Despite the benefits of gender mainstreaming, many pandemic responses have failed to adequately incorporate gender perspectives, resulting in missed opportunities to address gender disparities effectively [11].The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for a gender-responsive, intersectional approach to future health crises, emphasizing the importance of integrating gender considerations into all levels of policy-making and implementation [10, 12].

Given the intricacy and multidimensionality of gender justice, a comprehensive examination of this concept necessitates a thorough investigation within the relevant field. In this regard, qualitative studies of an in-depth nature offer a profound understanding of the subject matter under scrutiny. As such, the present research employed a qualitative approach to explore the nature of gender justice as experienced by nurses amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research has merely dealt with gender justice in nursing and policymaking during various crises separately, and considering the continuation of the COVID-19 pandemic and the possibility of similar ones in the future, it is necessary to make policies based on gender equality from the perspectives of nurses working in COVID-19 units. Given the complexity and multidimensionality of concepts, such as gender justice, a thorough investigation of said concepts within the desired field is imperative. In this regard, qualitative studies with an inherent depth are particularly valuable as they offer an intimate and insightful portrayal of the field under scrutiny. This study explored nurses’ perspectives on gender equality policies during the response phase of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The unique contribution of this study lies in its focus on frontline nurses’ perspectives regarding gender equality specifically within the context of management policies and resource allocation during the COVID-19 response phase. While previous research has broadly examined gender disparities in healthcare or workplace environments, this study highlights how these inequalities manifested in real-time crisis management—a context that exposed systemic gaps more starkly. This study breaks new ground by systematically examining structural gender inequities in crisis management during COVID-19, revealing how institutional policies perpetuated disparities despite formal equality measures. Through in-depth qualitative analysis, this study uncovered the lived experiences of structural gender inequities in pandemic crisis management, exposing how organizational cultures and hidden power dynamics systematically disadvantaged female healthcare nurses.

Materials and Methods

Study design and settings

This study was conducted using a qualitative content analysis approach in 2020-2021. In this study, the policy based on gender equality from the perspective of Iranian nurses in the COVID-19 units was analyzed using content analysis through Graneheim and Lundman model [13]. During the fieldwork phase, in-depth, face-to-face, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with 14 nurses working in COVID_19 units, with each interview lasting between 30 and 60 minutes. Participants were selected using purposive sampling, and data collection continued until data saturation was achieved. All interviews were recorded. A total of 14 participants were selected through purposive sampling to ensure representation of diverse and relevant perspectives. This number was deemed sufficient for generating rich qualitative data within the scope of the study. Data saturation, the point at which no new themes or insights emerged, was used to determine the adequacy of the sample size. Saturation was reached by the 12th participant, and the final two interviews confirmed the consistency and completeness of the identified themes.

Participants

In selecting participants, maximum diversity was considered in terms of age, gender, and marital status (Table 1).

Inclusion criteria were at least two years of clinical work experience, employment in one of the COVID-19 units, educational hospitals and medical centers in Iran, and participant’s desire to participate in the study. During the nurses’ shifts, the researcher approached the nurses eligible to participate in the study and arranged to meet with those who wished to cooperate after their shifts. The location and time of the interviews were selected according to the participants’ preferences; however, most interviews were conducted in restrooms after work shifts. The guiding questions for the interviews at this phase included the following. As the study progressed, data collection, simultaneous analysis, and the formation of categories influenced the direction of subsequent interviews:

● What were your biggest challenges at work during COVID-19?

● How do you perceive the effect of nurses’ gender differences during the COVID-19 pandemic on managers’ decisions?

● Can you provide an example of a policy that you found unfair or gender-based?

● What comes to mind when you come across the word gender justice in nursing policy?

● Was there a difference in access to protective equipment (e.g. masks, PPE) between male and female nurses?

● Did support policies (e.g. leave, psychological counseling) address the specific needs of female or male nurses?

● How do you see the performance of nursing managers in the COVID-19 crisis?

In addition, exploratory questions were also used to understand the interviewees’ experiences better.

As the interviews progressed, questions were grouped by topic to guide the conversation and help explore various dimensions of the topic:

1. Background and experience:

A. Can you tell me about your role and responsibilities during the COVID-19 response phase?

B. How long have you been working in the nursing profession?

2. Perceptions of gender equality in the workplace:

A. How would you describe the state of gender equality in your workplace during the COVID-19 response?

B. Did you notice any differences in how male and female nurses were treated or expected to perform during the pandemic?

3. Awareness and understanding of gender equality policies:

A. Were you aware of any gender equality policies implemented during the COVID-19 response?

B. How were these policies communicated to you and your colleagues?

C. In your view, were these policies effectively implemented?

4. Impact of policies on work and well-being:

A. Did gender equality policies influence your work conditions (e.g. shift assignments, workload, decision-making involvement)?

B. How did these policies affect your physical and mental well-being, if at all?

C. Can you describe any specific incidents where you felt supported or unsupported due to your gender during the pandemic?

5. Challenges and disparities:

A. Were there any specific challenges you faced as a nurse during the pandemic that you believe were related to gender?

B. Were caregiving responsibilities outside of work (e.g. family, children) considered or supported during the response phase?

6. Institutional support and leadership

A. How did leadership in your organization respond to gender-related concerns during COVID-19?

B. Do you feel your concerns or suggestions were heard and addressed?

7. Suggestions for improvement:

A. What do you think could have been done differently to promote gender equality more effectively during the COVID-19 response?

B. What recommendations would you give to health institutions for future emergency responses regarding gender equality?

8. Closing question:

A. Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience related to gender equality during the COVID-19 response?

Data analysis

At the end of the interviews, the participants were asked to speak freely in case of other points regarding the interview. All the interviews were recorded using a smartphone after taking the participants’ permission and were transcribed into written text immediately. The data were analyzed using content analysis through the conventional method and Graneheim and Lundman’s five-step conventional content analysis approach. The methodology applied by Gernheim and Lundman for data analysis was comprised of a sequential series of five distinct steps. First, following each interview, the transcriptions were meticulously scrutinized by reading them repeatedly, line by line and paragraph by paragraph, aimed at obtaining a comprehensive comprehension. Then, the primary codes were extracted. Afterward, based on similar codes, sub-categories, categories, and themes were formulated. The initial interview was then categorized, and the subsequent interviews aided in finalizing the primary category. Finally, an endeavor was undertaken to ensure the utmost homogeneity within categories and the most remarkable heterogeneity between categories [13].

Graneheim stated, “If the aim is to describe participants’ experiences of ordinary phenomena and the data is concrete and close to the participants’ lived experience, it may be wise to limit the analysis to categories at a descriptive level. If the analytic process continues too far, the results can become so abstract and general that they could fit into any context, and thereby say nothing about the participants’ unique experience in that situation” [13].

The preliminary codes were categorized and labeled based on their conceptual similarity (sub-categories). The sub-categories were compared and placed under main categories, which were more abstract (categories). The main categories were categorized under a more abstract concept (theme).

Rigor and reliable data

In order to ascertain the integrity of the data, four fundamental criteria—credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability—were employed, as delineated by Polit and Beck [14]. The investigator engaged in an extended sojourn at the various research sites, which facilitated the establishment of rapport with the participants and a deeper comprehension of the contextual factors at play. The participants’ feedback was additionally employed to authenticate the data and coding; subsequent to the coding process, the transcripts of the interviews were returned to the participants to confirm the fidelity of the codes and their corresponding interpretations. Moreover, the participants endeavored to represent a broad spectrum of diversity in terms of age, gender, experience, educational attainment, and professional settings. The supervisors meticulously examined the transcripts derived from the interviews. In conjunction with the supervisors, the derived codes and classifications were presented to several individuals well-versed in the nursing domain and qualitative research methodologies; these were subjected to thorough scrutiny. A high level of consensus was observed regarding the results extracted from the analysis. Ultimately, the categories and excerpts from the interviews were translated into English by a qualified translator and subsequently refined by a professional editor.

Results

The study was conducted with a cohort of 14 nurses who were working specifically in COVID-19 units, six of whom were identified as male. The initial analysis of the interviews led to the acquisition of 175 codes. The participants’ responses to the research question were organized into a main theme and its associated categories. Ultimately, the main theme was identified as “gender inequality in management policies and resource allocation,” with four categories labeled as “inefficient management,” “inequality in interactions,” “ inequality in the management of available resources,” and “inequality in consideration of staff needs” (Table 2).

The conceptual model of the acquired data is illustrated in Figure 1. This framework may serve for the subsequent purposes:

● Qualitative research on gender justice in healthcare management

● Policy analysis and development to promote equitable work environments

● Organizational audits focused on gender-sensitive planning and resource distribution

● Educational tools for nursing administration and gender studies

The main categories extracted in the present study, along with examples of the participants’ quotations related to the concepts, were as follows:

Inefficient management:

1. Managerial absence

2. Conflicts of rules and practices

As subcategories, the first category identified was inefficient management, which was derived from managerial avoidance and conflicts arising from incongruent rules and practices. Furthermore, the related concepts encompassed the dwindling presence of field managers, diminished responsiveness to challenges encountered by wards, non-adherence to a statute mandating the allocation of working hours based on work experience, marital status, and the number of children, the unavailability of a nurse of the same gender to provide exceptional care to patients, and a disparity in workload volume/type in relation to nurses’ gender and abilities.

In Iran, the provision of nursing care for female patients is predominantly carried out by female nurses, a practice shaped by prevailing cultural norms. Consequently, in cases where the female patient population surpasses the male patient population within the inpatient department and the female nurse’s counterpart is a male nurse, it results in an escalation of workload for the female nurse.

When female nurses were engaged in extended and frequent shifts, particularly those who were married and had a spouse and children, their attention toward their patients was diminished as a result of the substantial workload and obligations. Numerous statements articulated by the study participants with regards to the aforementioned concepts were as follows:

a. Concerning the concept of diminishing presence of field managers, one of the participants stated that: “I can almost say that the presence of some managers, in particular those who do most office work, not the ones with whom we have direct contacts, was deficient during this crisis. Practically, neither senior supervisors nor those whom I saw frequently before, like the infection control supervisors, who used to be around and whose main job should now be training other supervisors and generally the senior manager, were seen in the COVID-19 unit during this pandemic at all” (27 years old, female).

b. One of the participants reiterated the reduced responsiveness to challenges facing wards: “Due to the critical situation that occurred, we faced lots of problems in the wards. In these cases, we often used to call the supervisors, but unfortunately, the cooperation was not what it should have been” (27 years old, male).

Another nurse also stated, “Most nursing managers only insist that the work should be done anyway. Once the number of patients was very high and the workload was too high, they used to say that all work must be done anyway, and there was no way. They were adding fuel to the fire. However, at least it would have been better for them to give us a hand and get help from nurses from more private wards or be present in the ward themselves” (27 years old, female).

c. Regarding failure to comply with a statute for allocating working hours based on work experience, marital status, and the number of children, one of the participants added that: “During this time, shifts were very long, but the important thing was that it could become challenging for me if I was married, and I could not take care of the patients properly when I was on a shift” (30 years old, female).

One other participant also said: “Female co-workers who had small children had similar shifts to ours, but they were constantly worried and even cried during shifts, and we had to do their jobs as well” (32 years old, male).

d. Regarding the absence of a nurse of the same gender to provide exceptional care to patients, one of the participants stated that: “In our ward, as a COVID-19 unit, the patients’ families were not allowed to accompany them to help with some work. During most shifts, my co-workers and I were both men, and most of our patients were women, so we had hard times doing some procedures, such as bladder catheterization and intramuscular injection of drugs. The supervisors also did not help us” (28 years old, male).

Another nurse additionally maintained: “For example, one day, my co-worker was male. We divided the patients according to the care volume because we had to do so. My co-workers’ patients were women, so I had to do some of their care, and my workload multiplied” (30 years old, female).

Inequality in interactions

1. Gender-based planning in professional interactions

2. Proportional interaction requirements

The second category of the study was centred on the topic of “inequality in interactions”. This was derived from the proportional interaction requirements and gender-based planning in professional interactions. The category encompassed various concepts, such as respect and the role of gender in administrative interactions, privacy of nurses, enhancing caring relations and empathy during a crisis, and interactions based on an understanding of needs. Within the context of Iran, female nurses exhibit a tendency to engage in regulated interactions with male nurses and other individuals, influenced by religious considerations. Consequently, instances where their privacy is disregarded lead to feelings of insecurity. The study participants provided several statements based on the aforementioned concepts:

Regarding respect and the role of gender in administrative interactions, one of the participants noted that: “Our cooperation with different people was based on their moral characteristics in terms of gender. With a female co-worker, especially in terms of age, particularly when we were the same age, we could have a better and closer relationship” (27 years old, female).

Another participant said: “We were usually more comfortable with co-workers, who had the same gender, but we also had no problem with male counterparts, and we used to try to maintain respect at the time of crisis” (37 years old, female).

Regarding nurses’ privacy, one of the participants said, “There should always be a framework for relationships, but in any case, my security should never be violated.” (30 years old, female).

Moreover, another participant said, “During the COVID-19 crisis, we were all under much stress, but we would not like anyone to invade our privacy, and that was annoying” (28 years old, male).

One participant added regarding the increase in caring relationships and empathy during a crisis: “The difference between the COVID-19 crisis and normalcy was that our relationships became better and friendlier. The managers also became more intimate with us, and this helped us get through the difficult situation better” (28 years old, male).

Another participant said, “It was true that the number of patients increased and we were terrified of getting sick, but some nursing managers and supervisors became more intimate with us, even by talking on the phone, and showed more compassion, which was good and inspiring” (37 years old, female).

Regarding interactions based on an understanding of needs, a nurse stated, “I have a small child, and my parents are also sick, so I am always worried about transmitting the disease to them in shifts, and I do not focus on the care I provide, but someday Ms. Akbari (one of the supervisors) came to our ward and found out that I was distraught, so she talked to me and reassured me, and that was very good” (34 years old, female).

Inequality in the management of available resources:

1. Organizing personal protective equipment (PPE) by gender

2. Justice in resource allocation

The third category was related to the inequality in management of available resources, mined from organizing PPE by gender and justice in resource allocation, including concepts, such as medical and protective requirements based on gender, facilitated access to PPE, and gender-appropriate protective covers. Some statements provided by the participants based on the given concepts were as follows:

Considering the concept of medical and protective requirements based on gender, most participants in this study said, “Men care less about personal protection coverage than women, and they are more courageous in providing clinical care in COVID-19 wards” (37 years old, female).

Men’s valiant actions in tending to individuals afflicted with COVID-19 may pose a risk to their own well-being; nevertheless, it enhances their proficiency in attending to covid-19 patients.

One of the nurses also said, “At the onset of this crisis, due to severe shortages of PPE, they were rationed in the wards, and the head nurses were responsible for distributing the equipment between the nurses and other members of the treatment teams. Due to the cover we had on, in addition to the PPE, they got wet very quickly because of excessive sweating and had to be replaced sooner, but the number of our equipment was equal to that of men’s” (30 years old, female.

Regarding facilitated access to protective equipment, one participant said, “The head nurses, who were male, were much better at distributing protective equipment among the staff and better managing their shortages, but female head nurses and managers were more sympathetic to the staff and nurses. However, access to PPE was initially our biggest concern during the COVID-19 pandemic” (32 years old, male).

Regarding the concept of gender-appropriate protective covers, one of the participants stated, “Our covers were the same during the COVID-19 crisis because personal protective clothing was very similar, and there was no difference between men and women. Of course, we hardly knew each other, and communication was difficult” (27 years old, male).

Inequality in consideration of staff needs

1. Paying attention to staff demands

2. Importance of paying attention to psychological needs

3. Importance of paying attention to personal needs

4. Importance of paying attention to gender needs

The fourth category focused on the topic of disparity in fulfilling staff needs. It was drawn from considering the requirements of staff, their psychological needs, and their gender-specific necessities. The gender-related demands included a range of ideas, like suitable emotional and physiological needs based on gender and unique distinctions. The participants articulated several statements based on these aforementioned concepts, which included the following:

a. Concerning paying attention to gender-appropriate emotional needs, a participant said, “I have often experienced that the authorities have been less strict with men and have had higher expectations of us as women, making us resentful with this gendered view” (30 years old, female).

The occupation of nursing aligns closely with the emotional and nurturing characteristics traditionally associated with women, leading nursing supervisors to potentially have higher expectations of female employees in the nursing profession. The establishment of such anticipations may appear justifiable as it pertains to the psychological attributes exhibited by female nurses. However, disparities arise in the workplace where both male and female nurses are deemed equivalent in their occupational duties and remuneration, thus necessitating a mutual enhancement of their favourable demeanour when tending to patients.

b. In terms of paying attention to individual differences, one of the participants said, “In my opinion, the main problem facing nursing managers was that they had the same expectations from everyone, and during this crisis, they only paid attention to the performance of nursing duties and care and did not consider nurses and their abilities at all" (27 years old, male).

c. Regarding the concept of paying attention to physiological differences, a female nurse said, “Of course, I am not saying that women are less capable, but gender should be considered in the arrangement of shifts and wards. For example, I was on many shifts with a male co-worker; he used to help me a lot, did many activities that we could not do, and in general, it sometimes felt excellent to have a male co-worker in the ward” (30 years old, female).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed several primary causes of inefficient management in nursing, significantly impacting healthcare delivery. Key factors include inadequate support for nursing staff, ethical dilemmas in resource allocation, and the psychological toll on healthcare professionals. These issues collectively hinder effective management and care provision during crises.

Inadequate support for nursing staff

● Nurse managers often focused on logistical challenges, such as staffing and training, while neglecting the mental well-being of their teams [15].

● There was a critical shortage of PPE and other resources, forcing nurses to make difficult ethical decisions regarding patient care [16].

Ethical dilemmas

● The allocation of scarce resources, such as ventilators and ICU beds, raised ethical concerns about fairness and equity in patient care [16].

● Nurses faced the challenge of balancing personal safety with professional obligations, leading to moral distress [16].

Psychological impact

● The pandemic resulted in significant emotional strain on nurses, contributing to burnout and mental health issues [17].

● Support systems, including mental health resources, were often insufficient, exacerbating the challenges faced by nursing staff [18].

Conversely, some argue that the pandemic has also fostered resilience and innovation in nursing management, prompting the development of new strategies and collaborative practices that may enhance future healthcare responses.

The present study aimed to explore gender equality policies from the perspectives of Iranian nurses working in pandemic situation. The study findings accordingly shed light on gender inequality in the management policies and resource allocation. Several themes were also developed, including inequality in management, inequality in interactions, inequality in management of available resources, and inequality in consideration of staff needs. In the meantime, some concepts were extracted, such as conflicts of rules and practices, gender-based planning in professional interactions, organizing PPE by gender, and the importance of paying attention to psychological, personal, and gender needs, which will be discussed below.

Inefficient management was one of the issues affecting the nurses’ views. Among these issues was the managerial absence; for example, reduced responsiveness to challenges facing the wards, as expressed by the interviewees. The managerial absence was also a new concept that had not been explored in nursing and other fields. Another issue was the diminishing presence of field managers. For example, the study participants mentioned the absence of the infection control supervisor in the wards for direct control and training. In their study, Hesselink et al. also reported that the presence and availability of nurse leaders during daily work were significant from the perspectives of nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs) [19]. McSherry et al. also found that excellence in nursing care could occur if nursing managers and leaders had responded to the complexities of reforms and changes [20], which was in line with the results of the present study.

The findings of the current study also highlighted a failure to adhere to a particular statute concerning the distribution of working hours, taking into account factors, such as work experience, marital status, and the number of children. This serves as an illustration of conflicts arising from discrepancies between rules and actual practices. In this respect, Hoffman et al. established that nurses working 12-hour shifts were younger, less experienced, and more stressed than their co-workers who were working 8-hour shifts. Once the differences in nursing experience were controlled, similar stress levels were observed in the nurses [21].

Wang et al., in their study conducted in the nursing ward of a hospital, practically implemented sustainable support, dynamic human resource allocation, organization of pre-service training, monitoring of main stages of work, formulation of positive incentive methods, as well as the use of medical equipment [22]. They reported that such strategies had significantly boosted the capacity of the hospital nursing team to deal effectively with the COVID-19 pandemic Additionally, Wang et al. concluded that the reasonable allocation of the nursing workforce along with other strategies could ensure safe, effective, timely, regular, and sustained centralized treatment of COVID-19 [22].